Security and Stability in Turkey

Recent developments in Turkey have far-reaching implications. Domestic political instability, jihadist terrorism related to the war in Syria, and the newly inflamed Kurdish conflict have led to a marked deterioration in the country’s security situation over the last few years. What are the causes of this development, and what does the future hold in terms of Turkey’s stability?

By Fabien Merz

Turkey straddles the meeting point of Europe and Asia – geographically, politically, and culturally. An emerging economy, it is a member of the G20, the OECD, NATO, as well as a candidate for EU accession. Its geographic location not only makes Turkey a key player in the region but also means that the country’s stability is of strategic importance to Europe and the West. As such, Turkey is asserting its influence in the civil war in neighboring Syria and plays a crucial role in managing refugee flows, the global fight against terrorism, and the security of NATO’s southeastern flank.

About a decade ago, prime minister Recep Tayyip Erdogan’s AKP (Justice and Development Party), a socially conservative party with roots in political Islam but liberal in economic issues, seemed to have successfully reconciled an explicitly Sunni Muslim identity with parliamentary institutions, democratic principles, and a pro-Western stance. However, by the summer of 2013, the limits of this course had become apparent with the violent suppression of the Gezi Park protests against Erdogan’s increasingly authoritarian tendencies and his policies increasingly perceived as creeping Islamization.

Since then, the authoritarian tendencies of Erdogan have indeed intensified. In July 2016, amid political tensions and an increasingly polarized Turkish society, the country experienced a failed military putsch. The government responded with sweeping “purges” that also affected large parts of the security forces. All this coincided with a proliferation of jihadist terrorism within Turkey spilling over from the Syrian civil war. Furthermore, the Kurdish conflict has seen a massive re-escalation since mid-2015. All of these events contributed to a significant deterioration of stability and security in Turkey in the past few years. This analysis will take a closer look at the driving factors behind this development, with a particular focus on their implications for the security situation within Turkey.

An Authoritarian Turn

After the AKP and its co-founder Erdogan rose to power through democratic elections in 2002, Turkey initially instituted a series of reforms that led to strong economic growth and an entrenchment of democratic principles, together with a pro- Western stance. Official accession negotiations between Turkey and the EU began in 2005.

The first noticeable cracks in this new picture of Turkey appeared in 2008, when, responding to internal power struggles, waves of arrests and trials of political opponents revealed Erdogan’s drift towards authoritarianism. The true turning point however occurred in the summer of 2013, as the government violently responded to the Gezi Park protests. These demonstrations had initially focused on protecting Istanbul’s green spaces from construction projects but soon grew massively in size and increasingly turned against Erdogan himself and his authoritarian tendencies as well as his policy of gradual Islamization. The Turkish government was admonished for its crackdown on the protests, including by the US and the EU, which subsequently placed its accession talks with Turkey on hold.

The tendencies within Erdogan’s AKP government to undermine democratic standards and subvert the secularist principles enshrined in the Turkish constitution have since become systematic in nature. Erdogan’s government has, among other things, increased the pressure on civil society actors and the media, periodically limited access to various social media, and passed laws that have further eroded the constitutional mechanisms for controlling the executive as well as the principles of secularism. These developments led the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe to note in a resolution in June 2016 that recent developments in Turkey pertaining to freedom of the media and of expression, erosion of the rule of law, and human rights violations have raised serious questions about the functioning of its democratic institutions.

These developments further strongly polarize the Turkish population. Erdogan is supported by the rural, often poorer, and more religious classes, while the coastal and generally more secular urban centers, as well as the majority of the ethnic Kurds strongly oppose his policies. Rural support has allowed the AKP and Erdogan to decide crucial elections in their favor, though sometimes only by slim margins. This includes the parliamentary elections of 2011 and, after snap elections, also in 2015, as well as the highly controversial constitutional referendum of 2017.

There have also been repeated power struggles between different interest groups within the Turkish state – including between the AKP and one of its former allies, the Islamic Gülen movement, which was mainly entrenched in Turkey’s judicial and educational systems. The AKP responded with dismissals and arrests of political opponents, both within and outside the state structures.

A Coup Attempt and its Aftermath

It is in this domestic climate marked by internal power struggles and an increasingly polarized society that a military coup took place during the night of 15 July 2016. The government blamed the Gülen movement for the attempted putsch. The ruling AKP and Erdogan responded with mass arrests of suspected Gülen sympathizers in the public administration, the judiciary system, and among the military and security forces. Within just a few days, tens of thousands of state employees had been suspended or arrested – mainly soldiers, police officers, judges, and state prosecutors. Among those arrested and dishonorably discharged were also more than 160 admirals and generals – which amounted to almost half of the effectives in these ranks. Further, under the terms of the newly declared state of emergency, around 120,000 people had been sacked and around 40,000 arrested by April 2017. Observers point out that the government also used the attempted coup to justify even harsher measures against political opponents and critics of the government who had not been involved in the aborted coup.

In addition to the destabilizing effects of the putsch itself and its influence on the further stiffening of the government’s repressive course, the “waves of purges” among the security forces are of particular importance for the security situation in Turkey, impeding the Turkish state’s ability to adequately deal with the other security policy challenges facing the country. In these regards, jihadist terrorism spilling over from the war in Syria and the Kurdish conflict, which has once more escalated into open fighting, are particularly worrisome

Turkey and the “Islamic State”

One of the main security policy challenges currently facing Turkey is related to the jihadist militias fighting in the war in Syria. Especially until mid-2015, there had been widespread accusations that Turkey was passively or in certain instances even actively supporting jihadist militias operating in Syria, including the “Islamic State” (IS). The charges ranged from implicit permission for personnel and material reinforcements to cross the border and purchases of oil extracted by the IS to more active supply of weapons and material.

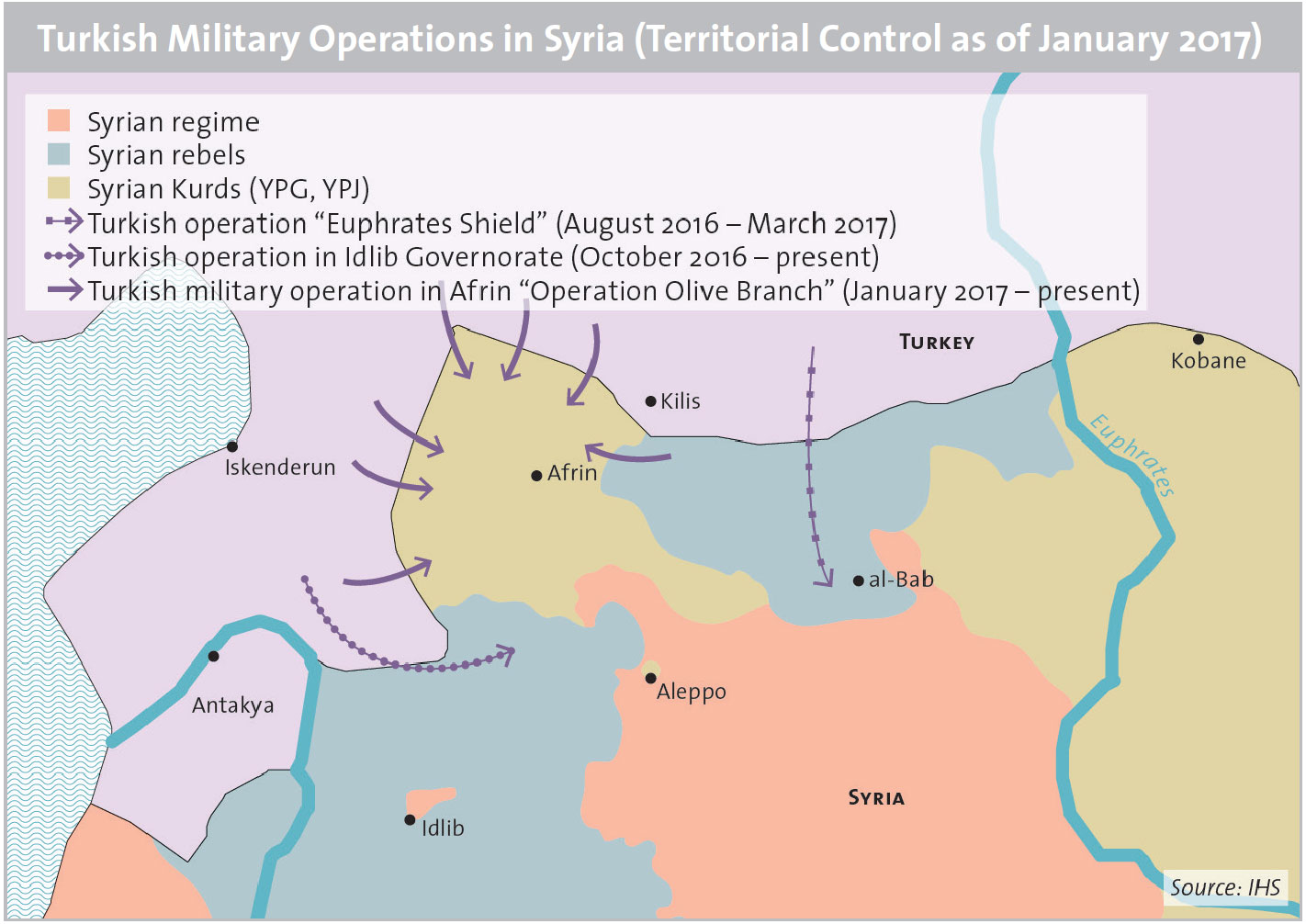

It is currently difficult to assess the degree of veracity of these accusations independently. However, Turkish support for jihadist militias could to some extent be rationalized on the basis of Ankara’s strategic imperatives in Syria. At least in certain areas – and especially in the initial stages of the Syrian civil war – there was indeed an undeniable convergence of Turkey’s interests in Syria with those of jihadist militias, including, from 2013 onwards, IS. For instance, IS was engaged in bitter fighting with the Syrian Kurds in northern Syria, near the Turkish border. In the chaos of the civil war, the Syrian Kurds had quickly established control of the areas in which they formed the majority, and had proclaimed the de-facto autonomous region of Rojava along the Turkish border (see map). Ankara regards the strongest of the Syrian Kurdish militias, the People’s Protection Units (YPG) and the Women’s Protection Units (YPJ), as extensions of the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK), and thus as terrorist groups. Therefore, based on considerations related to the Kurdish issue in Turkey, Ankara’s main priority has been to weaken the Kurds of Syria as far as possible. Also, jihadist groups, including IS, managed to build themselves up as a counterweight to Bashar al-Assad’s regime within the Syrian conflict from 2013 onwards, against which Turkey had taken a clear position since the start of the uprising in 2011.

About-face: Turkey Changes Course

Initially, Turkish authorities argued that concerns over retaliatory attacks prevented a more determined stance towards IS. Irrespective of whether accusations of Turkey adopting a laissez-faire or even cooperative stance vis-à-vis the jihadists are true, it is notable that Turkey’s posture towards IS has significantly hardened since mid-2015. The pressure US and its allies exerted on Ankara to take a more aggressive approach in dealing with IS might be one of the reasons causing this Turkish about-face.

At the end of July 2015, the Turkish authorities carried out large-scale raids, including against jihadist networks operating on the country’s territory. Also, from late July 2015 onwards, the US was granted permission to use the Incirlik air base for its campaign against IS, which Turkey had initially refused despite having been a member of the international coalition against IS since September 2014. Moreover, in August 2016, Turkey staged a military intervention in northern Syria – officially, in order to push IS out of the areas under its control along the Turkish border. However, that intervention simultaneously allowed Turkey to prevent the Syrian Kurds from establishing a geographic link between the areas under their control in northern Syria, and thus weakened their position in Syria (see map).

From the summer of 2015 onwards, IS responded to Ankara’s tougher stance by stepping up the number of attacks inside Turkey. Unlike earlier IS operations within the country, this wave of attacks was not primarily directed at Kurdish or Kurdish-linked targets, but directly and systematically targeted the Turkish state and Turkish society. In October 2015, a bomb was detonated in Ankara. In January and March 2016, Istanbul was hit by suicide attacks, and in June of the same year, Istanbul’s Atatürk airport was attacked. In January 2017, the chosen target was a nightclub in Istanbul. This campaign of IS killing and injuring hundreds, which partially coincided with massive post-coup purges of the security forces, caused a significant deterioration of the security situation in the country.

The Kurdish Question

The Kurdish conflict, which has festered in Turkey for decades, has led to further negative effects on the security situation and stability of the country. From 2013 onwards, progress had initially been made in the peace talks between the Turkish government and the PKK. Despite these successes, however, the peace was an extremely fragile one. Tensions flared up anew when the Kurdish border town of Kobane was besieged by IS in the winter of 2014/2015. During the initial stages of the siege, Turkey refused to allow any supplies to reach the city, which was cut off on the Syrian side by IS and held by YPG and YPJ fighters. This prompted increasingly vociferous accusations by Turkish Kurds towards the Turkish government for allegedly allowing IS to operate on its territory, of instrumentalizing IS against the Kurds, and even of actively supporting the group. As a result, tensions and Kurdish protests broke out in Turkey in late 2014.

A Conflict Rekindled

In July 2015, IS carried out devastating attacks against a gathering of the pro-Kurdish HDP opposition party, followed just weeks later by a comparable attack on an event organized by a pro-Kurdish youth party. Groups with links to the PKK retaliated with attacks against Turkish security forces for their perceived inaction and complicity. These developments set off a chain reaction of Turkish air strikes against PKK targets in northern Iraq, new waves of arrests in Turkey, and new attacks by the PKK and other Kurdish groups that ultimately caused the peace talks to break down.

The cycle of violence culminated in a series of attacks by the PKK and other Kurdish groups and a large-scale operation by the Turkish security forces in southeastern Turkey, where most of Turkey’s ethnic Kurdish minority lives. According to the UN and various human rights organizations, the Turkish security forces also indiscriminately assaulted civilians living there. The International Crisis Group assesses that about 3,300 people were killed in clashes between the Turkish security forces and Kurdish groups between July 2015 and March 2017.The newly inflamed Kurdish conflict in Turkey in conjecture with IS’s terrorist campaign have destabilized the security situation in Turkey and caused it to further deteriorate.

It is difficult to assess to what extent strategic considerations of the AKP regarding the July 2015 parliamentary election in Turkey may have played into the escalation of the Kurdistan conflict. These elections had seen the AKP lose its parliamentary majority for the first time since 2002 due to a stronger showing by the pro-Kurdish HDP. Erdogan and the AKP were accused of stoking the conflict and using it to whip up nationalist fervor against the Kurds and the HDP in order to retake the parliamentary majority at snap elections called in November 2015.

Outlook

The domestic political climate, marked by severe polarization in society and political jockeying, together with the rekindled Kurdish conflict and IS’s terrorism campaign, added up to a unfavorable amalgamation of factors that have had severely deleterious effects on Turkey’s stability and security situation in recent years.

While IS may be almost vanquished in military terms, its ability to carry out attacks in Turkey is by no means broken. Moreover, in October 2017, Turkey intervened militarily in Syria’s Idlib province (see map) with the stated aim of establishing a humanitarian corridor. However, observers point out that Turkey also aims at containing a possible Kurdish expansion and encircling the Kurdish-controlled Afrin region. There are furthermore indications that Turkey to a certain extent seems prepared to tolerate jihadist groups close to al-Qaida that have a strong foothold in the province. Whatever its motives, Turkey risks creating new acute security problems in the future due to its prioritization of antagonizing the Syrian Kurds, similarly to what it had also been accused of in its dealings with the IS. In the long term, the presence of jihadist groups in Idlib serves nobody’s interests, including Turkey’s. IS’s terrorist attacks should have clearly shown that jihadists can also target Turkey when circumstances change.

Implications for Switzerland

The security situation in Turkey also has implications for Switzerland. In 2015, Switzerland was the 12th largest international investor in Turkey. Security of Swiss citizens in Turkey is also of importance. In 2016, some 215,000 Swiss tourists visited the county, while 4,422 Swiss citizens were residents in Turkey. In adition, events in Turkey can also lead to political tensions and even violence between diaspora communities living in Switzerland.

Despite the Turkish efforts to keep the Kurds of Syria as weak as possible, the latter currently control large parts of the border region on the Syrian side. They have established themselves as a key actor in any future solution of the Syrian conflict, and they benefit from support and political backing from the US and Russia. The Turkish military operation in Afrin, in northern Syria, which began in January 2018 with the aim of driving the YPG/YPJ forces out of the region, creates further considerable risks for stability and security within Turkey. While the operation is in line with Ankara’s security policy priorities – preventing the establishment of an autonomous Kurdish territory on its border – it could also lead to more cross-border solidarity among the Kurds, as was the case during the Kobane siege of 2014/2015, and therefore risks further fanning the flames of the Kurdish conflict within Turkey.

The country will therefore continue to face acute security policy challenges in the near future. In July 2017, a constitutional referendum was adopted by the slimmest of majorities that will massively strengthen Erdogan’s powers at the expense of the judiciary and the parliament. It remains to be seen whether this reform will stabilize the situation in Turkey, as its advocates expect, or whether it will reinforce the government’s authoritarian course by eroding the separation of powers, as the critics fear. The majority of independent observers in Western Europe and North America believe that the latter scenario, potentially causing more instability, is the likelier one.

Turkey today finds itself at a crossroads. Will the country manage to heal the wounds of domestic strife and extricate itself from the destabilizing vortex of Syria’s civil war? The answer will ultimately not only determine the security, the stability, and ultimately the development of the country itself. Due to Turkey’s geostrategic importance, it will also influence the stability and security of the entire region, of Europe and the West at large.

About the Author

Fabien Merz is a Researcher in the think-tank team “Swiss and Euro-Atlantic Security” at the Center for Security Studies (CSS) at ETH Zurich. Among other things, he is the author of “Dealing with Jihadist Returnees: A Tough Challenge” (2017).

Editor: Christian Nünlist