The Relevance of the Cold War Today

25 May 2016

By Barbara Zanchetta for Geneva Centre for Security Policy (GCSP)

This article was external pageoriginally publishedcall_made by the external pageGeneva Centre for Security Policy (GCSP)call_made in May 2016.

Is there, or not, a legacy of the Cold War that continues to define the international system?

The Cold War divided Europe and the world in two opposing spheres of influence for four and a half decades. The emergence of the United States as a dominant international actor following the Second World War was shaped by the rivalry with the Soviet Union, which, in turn, defined its new global posture on the basis of the competition with America. Cold War necessities came to dictate both superpowers’ foreign and defence policies for decades. While historians agree on assessing the Cold War as an important chapter in the turbulent history of the twentieth century, far less consensus exists among analysts on the contemporary relevance of the bipolar conflict. In other words, is the Cold War still relevant today, or was it just a passing – albeit important – historical phase? Is there, or not, a legacy of the Cold War that continues to define the international system?

This paper argues that the bipolar conflict shaped the international system in ways that are still very much relevant today. The easiness with which Western commentators talk about a ‘new Cold War’ with Russia – whether in the context of the crisis in the Ukraine or of the conflict in Syria – testifies to the enduring notion of an inherent and deeply rooted rivalry between Washington and Moscow. A Cold War mentality of distrust seems to define the language used in describing Russia, still seen as an international actor whose ambitions and objectives are not shared by the United States and the rest of the – however ambiguously defined – Western world.

In addition to an enduring Cold War mentality and easily resurfacing rhetoric, the legacy of the Cold War and its relevance for contemporary politics rotates around at least three more tangible elements: (i) the former superpowers’ nuclear arsenals and the related arms control and non-proliferation treaties, negotiated during the Cold War; (ii) local conflicts or interventions that originated during the Cold War, but whose consequences and ramifications endure today; (iii) the continued presence and relevance of international institutions – such as the European Union and NATO – whose origins lie in the Cold War division of Europe.

Key Points

- Beyond the easily re-surfacing rhetoric on a ‘new Cold War’ when referring to the Western world’s relationship with Russia, the bipolar conflict (1945-1989) shaped the international system in tangible ways that remain highly relevant today.

- The concrete legacy of the Cold War rotates around three elements: nuclear weapons and the related arms control and non-proliferation treaties; local conflicts with long-lasting consequences; and international institutions that continue to play a key role today.

- Current instability in the world’s hotspots – from the Korean peninsula to Afghanistan – cannot be understood, nor future courses charted, without turning to the Cold War in search for the roots and causes of today’s dilemmas.

- The major institutions that govern the ‘West’ – NATO and the EU – are both rooted in the bipolar era, and the sense of community, belonging and shared values that characterise them was forged throughout the decades.

1. Nuclear weapons and arms control treaties

At the dawn of the nuclear era, the United States had hoped to maintain the monopoly over nuclear technology and nuclear weapons. However, four years after the explosion of the nuclear bombs in Hiroshima and Nagasaki,the Soviet Union tested its first nuclear device, unleashing the nuclear arms race. During the 1950s, the United States expanded its nuclear weapons programs, seeking to compensate its alleged conventional weapons inferiority in Europe by relying on the doctrine of massiveretaliation. Nuclear deterrence therefore came to shape the defence posture of the superpowers and MAD (mutual assured destruction) became a defining feature of the Cold War.

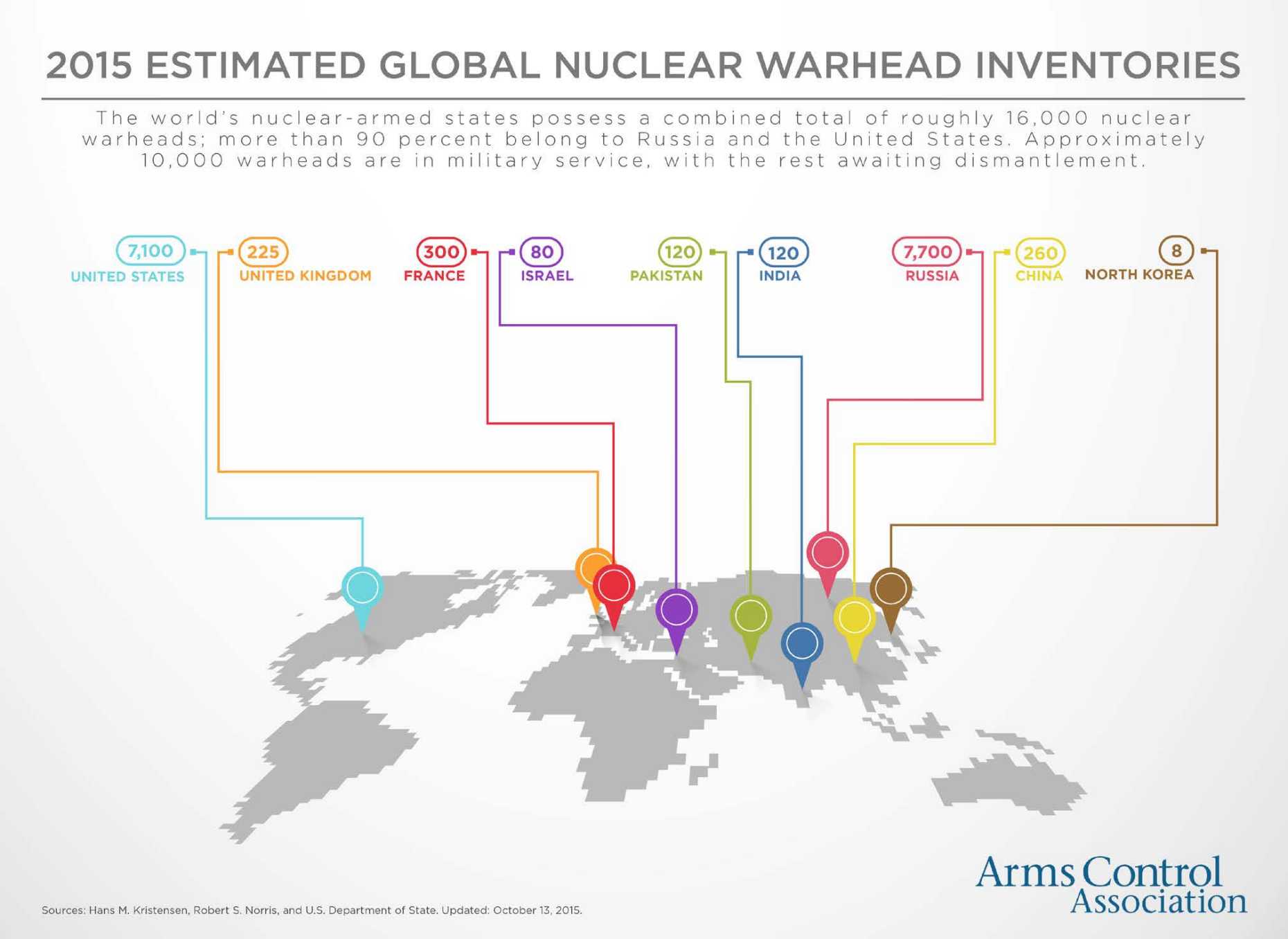

The arms race between the United States and the Soviet Union induced other major powers to seek their own independent nuclear deterrent, thus leading to an initial, limited proliferation of nuclear weapons. The United Kingdom (1952), France (1960) and the People’s Republic of China (1964) in fact tested their own nuclear devises, and nuclear weapons became a seemingly permanent element of the international system.

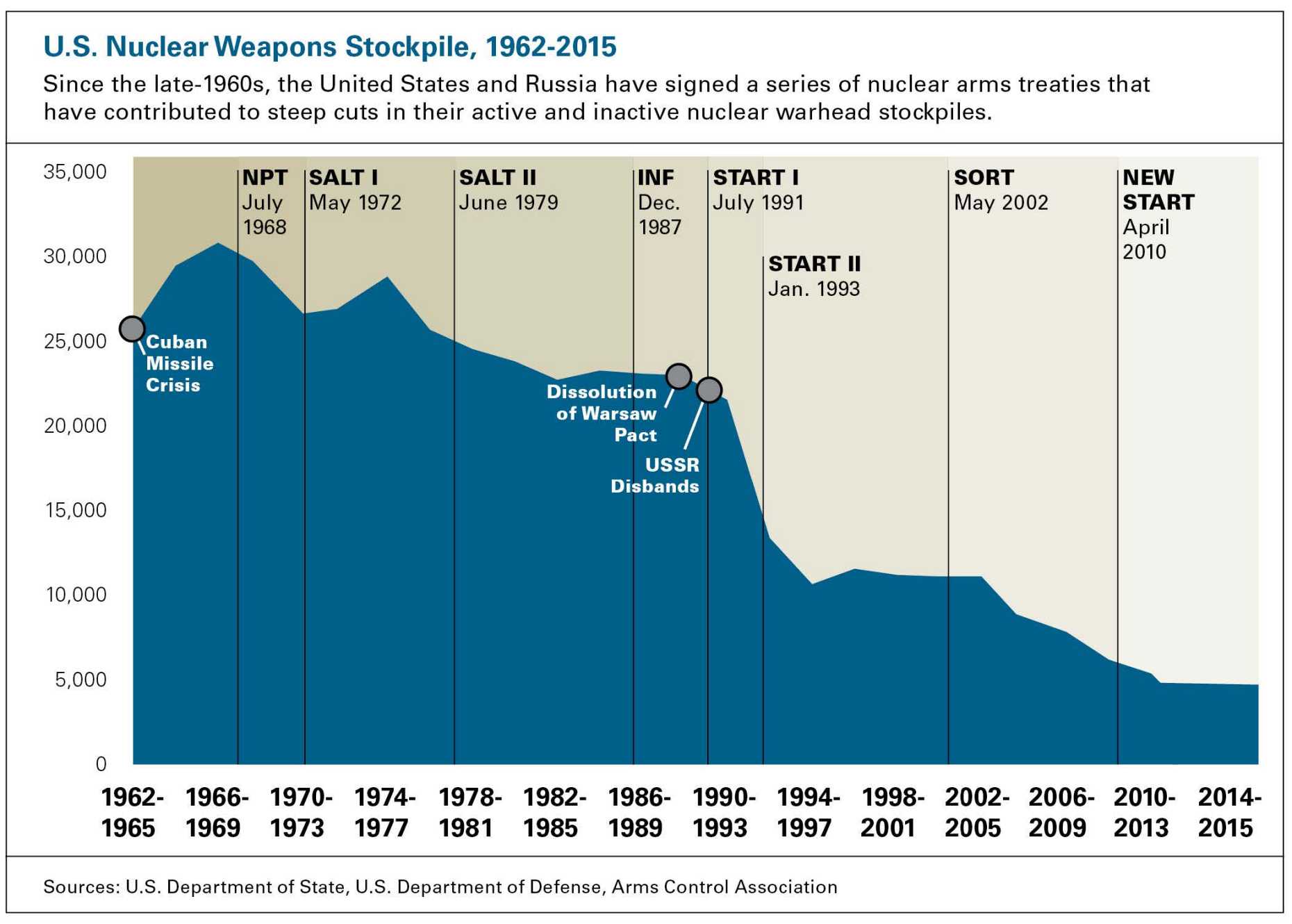

However, following the Cuban missile crisis of 1962 – when the superpowers had come dangerously close to a nuclear exchange – Washington and Moscow started to engage in the first arms control negotiations in order to reduce the future possibility of nuclear war. This gradual reduction of tension between the superpowers led to the successful conclusion of the multilateral Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (1968) and the beginning of strategic arms limitation talks (SALT) between the United States and the Soviet Union.

At the time of the negotiations on the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT), nuclear proliferation threatened to further destabilize the international system, as analysts predicted that 20-25 states would acquire nuclear weapons within 20 years. The impetus behind the NPT was, in fact, the need to prevent a world with many nuclear weapon states. The Cold War nuclear deterrent between the US and USSR was dangerous, but stable. Having more nuclear weapon states would multiply the risks of miscalculation, accidents, unauthorised use of weapons and increase chances of escalation from conventional to nuclear war in case of conflict.

Freezing the situation as it was in the late 1960s, the negotiations were in essence based on a bargain between the non-nuclear weapons states – that agreed never to acquire nuclear weapons – and the five nuclear weapons states – that agreed in exchange to share the technology for the peaceful use of nuclear weapons and to pursue nuclear disarmament in order to, ultimately, eliminate their nuclear arsenals. The NPT was signed in July 1968, and entered into force in March 1970. From the initial 40 signatory states, required for the treaty to become effective, 190 states are now party to the treaty. While it was initially meant for a limited duration of 25 years, the parties agreed to extend the treaty indefinitely at the review conference of 1995.

Today, the vast majority of states are members of the NPT. However, four UN member states never joined the treaty – India, Pakistan, Israel and South Sudan (that separated from Sudan only in 2011). North Korea acceded to the treaty in the 1980s, but announced its withdrawal in 2003. Of the non-party to the NPT states, three have tested nuclear weapons – India (1974), Pakistan (1998) and North Korea (2006). Israel, instead, has maintained a policy of so-called nuclear ambiguity, neither confirming nor denying the possession of nuclear weapons (but is widely believed to possess nuclear weapons).

In parallel with the multilateral negotiations that led to the signing of the NPT, the United States and the Soviet Union started bilateral talks to limit the size of their nuclear arsenals. The Strategic Arms Limitation Talks (SALT) started in the late 1960s and led to the signing of two landmark treaties in 1972 and 1979. Although the SALT I and SALT II treaties codified a persistently high level of nuclear weapons, they initiated an arms control process that was, despite setbacks, never interrupted. The SALT treaties in essence set the basis for the nuclear arms reduction talks (START), the agreements reached between the US and Russia in the post-Cold War era.

Both the NPT and the US-Soviet/Russian agreements had and continue to have many problematic features. Critics of the NPT underline the importence of the international community in preventing the proliferation of nuclear weapons in the states not party to the treaty, as well as the difficulty in monitoring the exclusively peaceful nature of nuclear programs, with the Iranian case, in this context, being exemplary. Furthermore, the non-nuclear weapons states have charged that while their side of the “bargain” has been respected, in essence condoning a world with the “haves and the haves not”, the nuclear weapons states have not maintained their treaty commitments in all aspects related to nuclear disarmament. Almost fifty years from the signing of the treaty, in fact, it is still difficult to imagine a world without nuclear weapons. The national security strategies of the nuclear weapon states still openly rely on nuclear weapons as a crucial element of their defence.

The US-Russian agreements are instead criticised for allowing the former superpowers to maintain an excessive number of nuclear weapons. Despite the drastic reduction in the size of their nuclear arsenals – now at less than one-fifth compared to the height of the arms race in the 1960s – the United States and Russia still possess more than enough strategic warheads to deter a nuclear attack, and they are both still updating and modernizing their delivery systems. Should these weapons be used, even in a “limited” way, the result would be catastrophic.

Notwithstanding the many problematic aspects of the NPT, and the thousands of nuclear weapons still present in the stockpiles of the United States and Russia, these agreements continue to define the international system today. The NPT remains the only treaty that regulates nuclear proliferation, while the bilateral US-Russian treaties provide for verification mechanisms that maintain the level of weapons under control and prevent both sides from developing more weapons in the future.

2. Local conflicts and superpower interventions

From the early 1950s onwards, the Cold War ‘order’ stabilised the division of Europe and the bipolar competition moved outside the old continent to become increasingly more global. This process was aided by the nuclear balance of terror between the superpowers, which led Washington and Moscow to avoid direct confrontation. Local conflicts therefore assumed a greater significance in the worldwide struggle to gain influence and supremacy.

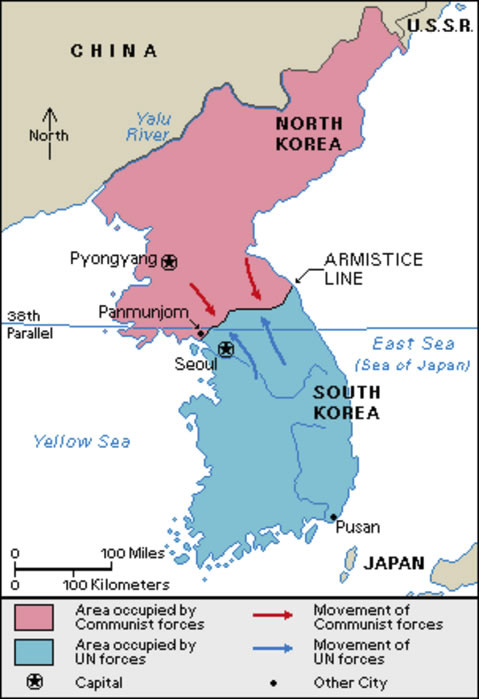

The first signal that the Cold War had moved outside of Europe came with the escalation of tension in the Korean peninsula. During the Second World War, Korea was liberated from Japanese forces by both the US forces – that entered to country from the south – and the Soviet forces – that invaded from the north. The line of separation between the two was marked by the 38th parallel. As the Cold War came to dominate the relationship between the two former allies, Korea – like Germany – remained divided.

In 1947, the issue of Korea was deferred to the newly created United Nations. Elections were held and two states were created, each under the sphere of influence of the US (South Korea) and the Soviet Union (North Korea). However, in an attempt to reunite the country, in June 1950 the Soviet-backed North attacked the South, thus initiating the Korean War.

In the United States, the North Korean move was interpreted as a confirmation of Soviet expansionist ambitions. This perception triggered an escalation and further militarization of the Cold War. In fact, only months before the Korean War, the newly created People’s Republic of China and the Soviet Union had stipulated an alliance, seen by the United States and the Western world as the coalescing of two Communist “giants” into a strong and menacing bloc. The need to stop the advance of North Korea and the unification of Korea under a communist government therefore came to symbolize the global fight between East and West, of capitalism versus communism.

Following months of fighting, the UN-sponsored (but mainly American) forces pushed the North Koreans back across the 38th parallel, re-establishing the status quo ante. The armistice line of July 1953 again separated the two Koreas and their opposing political systems. This is the same armistice line that continues to divide the Korean peninsula today.

While the Korean situation escalated into open war, in a number of other countries the United States and the Soviet Union fought for influence in more subtle – though no less destabilizing – ways. An example of American involvement with long-lasting consequences was the decision to back the 1953 coup d’état in Iran that ousted the democratically elected government led by Mohammed Mosaddegh and strengthened the rule of Shah Mohammed Reza Pahlavi. Mosaddegh had challenged the British and American influence by nationalizing the Anglo-Iranian Oil Company in order to allow Iran to have a more equitable share of its profits. Assessed in Washington as too left leaning and as not sufficiently aligned with Western interests, Mosaddegh was removed from power in a CIA- orchestrated coup.

Although in the case of Iran the advancement of Soviet or Soviet-inspired influence was only supposed (and proved to be misguided), Moscow’s interventions in other so-called Third World countries were actual, and prompted American reactions of different kinds. Countries considered to be in the periphery compared to the focal areas of the Cold War – such as Angola – became important for Washington because of the advancement of Marxist influence, sponsored either directly or indirectly by the Soviet Union. As US Secretary of State Henry Kissinger put it, “it was not the intrinsic importance of Angola,” that mattered, but “the implications for Soviet foreign policy and long-term East-West relations.”[1] Accordingly, the US aided the anti-communist factions and tried to match the Soviet influx of weapons into the Angolan conflict until a negative vote of the US Congress which, in the immediate aftermath of the fall of Saigon, wanted to avoid foreign interventions that evoked Vietnam-like situations (even if the interventions were of covert nature, such as in Angola).

The Angolan Civil War triggered alarm bells in Washington on Soviet expansionist ambitions in the Third World, confirmed (from the US viewpoint) a few years later in the context of the Ethiopia-Somalia Ogaden War (1977-1978). The Soviet Union in fact openly intervened in favour of the newly established Marxist regime in Ethiopia, betraying its former ally, Somalia. In response, the United States started to provide aid to Somali dictator Said Barre, in essence implementing a reversal of alliances in order to counter perceived Soviet expansionism in a strategically important area – the Indian Ocean, the Gulf of Aden, the Red Sea and, ultimately, the entire Middle Eastern region.

The notion – circulating in Washington in the later part of the 1970s – of a Soviet master plan to conquer warm water ports in the Persian Gulf seemed to be confirmed by the invasion of Afghanistan in December 1979. Following the Iranian revolution and the departure of the Shah earlier that year, the United States had lost its major ally in the region and the main bulwark against Soviet penetration of the Persian Gulf. For this reason, the Carter administration was determined to block the advancement of the Soviet Union in the area. In an effort to make the Soviets pay a heavy price for their intervention, the US initiated a covert program of aid to the anti-Soviet fighters in Afghanistan, the mujahidin (the “soldiers of God”). The program was continued and expanded during the Reagan years and became the greatest covert operation in the history of the CIA.

In all of these cases, the superpower rivalry played out in the so-called periphery had long lasting regional consequences, most of which still resonate today. The US complicity in the overthrow of Mosaddegh and the subsequent support for the Shah of Iran marred US-Iranian relations for years and played a part in building up the stanch anti-Americanism of the Islamic Republic of Iran. The Angolan Civil War endured for decades until well after the end of the Cold War, devastating the country’s infrastructure and economic enterprises. While Ethiopia successfully managed a constitutional transition after the end of Mengistu’s regime in the early 1990s, Somalia’s fate was far more tumultuous. The ousting of Said Barre was followed by civil war, with various factions controlling parts of the country but never establishing a central government. In the early 1990s, Somalia was classified as a “failed state” and instability, factionalism, poverty and weak government institutions continue to characterize the country today. In Afghanistan, the Soviet withdrawal left a country devastated and divided, which would first descend into civil war and then witness the rise and consolidation of Islamic extremism, with the emergence of the Taliban in the early 1990s. Moreover, US support for the Islamic mujahidin fighters indirectly aided the rise of transnational Islamic terrorism, which would later dramatically target America itself on 11 September 2001.

These countries and regions remain hotspots today, due to the fragility of state structures, extremism and overall instability, which has proved to be fertile ground for the growth and expansion of terrorist networks. Not only is the Cold War to blame for this, as the superpowers, blinded by their great power rivalry, overlooked and sometimes exploited problematic local realities. But present dynamics cannot be understood, nor can future courses be charted, without turning to the Cold War in search for the roots and causes of today’s dilemmas.

3. Institutions – NATO and the EU

Although the Cold War came to touch the entire world, its origins were in the post-World War II division of Europe. The liberation from Nazi occupation left the continent divided. The presence of Western and Soviet forces gradually translated into spheres of influence, as the Cold War came to define the relationship between the West – led by the United States – and the Soviet Union. While US President Franklin Roosevelt had hoped to cooperate with Stalin in the post-War settlement and reconstruction of Europe, following his death the relationship with Moscow rapidly deteriorated. The West interpreted various signals – from Stalin’s 1946 “inevitability of conflict” speech, to the difficulty in cooperating on Germany and the occupation of Eastern Europe – as demonstration of Soviet intransigence and aggressiveness. In March 1946, former British Prime Minister Winston Churchill famously captured the sense of a looming Cold War by stating:

“From Stettin in the Baltic to Trieste in the Adriatic an Iron Curtain has descended across the Continent. Behind that line lie all the capitals of the ancient states of Central and Eastern Europe. Warsaw, Berlin, Prague, Vienna, Budapest, Belgrade, Bucharest and Sofia; all these famous cities and the populations around them lie in what I must call the Soviet sphere, and all are subject, in one form or another, not only to Soviet influence but to a very high and in some cases increasing measure of control from Moscow.”[2]

In order to counter the perception of an impending Soviet threat in Europe, the Western camp merged to form various institutions that would ensure its cohesion from both an economic and military point of view. The first coordination of European economic policies was introduced to manage the European Recovery Program (that came to be known as the Marshall Plan, taking the name from US Secretary of State George Marshall). Then, in order to overcome the fears of German resurgence, while at the same time charting a path for German recovery (vital for the revival of the entire continent), French Foreign Minister Robert Schuman proposed the creation of a supranational authority to control the production of steel and coal in France and Germany, open for membership to other countries. The European Coal and Steel Community was established in 1951, with six member states (France, West Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, Belgium and Luxemburg). This set the basis for the creation of the European Economic Community in 1957, as the principle of supra-nationalism was expanded to include other sectors of the European economies. The EEC established a common market and customs union; closer union among the peoples of Europe; and, in general, the pooling of resources to strengthen peace.

While the United States oversaw and encouraged the economic integration of Europe, it was to remain the senior partner in all aspects related to military defence. Marking a significant turning point in the history of American foreign policy – which had until then, in the words of George Washington, avoided “entangling alliances” – in 1948 the US Senate passed a resolution (named after Senator Arthur Vanderburg) that allowed the United States to take part in permanent regional accords, if and when these directly related to the defence of American national security. This paved the way for the signing of the North Atlantic Treaty a year later. Then, as the Cold War escalated (following, most notably, the explosion of the Soviet atomic bomb and the beginning of the Korean War), the member countries of the treaty agreed to create a permanent organization, NATO – initially based in Paris – and to strengthen its military integrated structure.

Although both NATO and the European Union (established by the Maastricht Treaty of 1992, which significantly expanded the competences of the EEC, including the creation of a single European currency) have obviously evolved into organizations with different mandates compared to their origins, it is important to recall that both institutions were inherently linked to the Cold War. It was at a time when the European countries and the US shared the perception of a common threat that the transatlantic ties were created, strengthened and expanded. While analysts had predicted the dismantlement of NATO following the end of the Cold War (as its core mission seemed to have evaporated), the alliance not only remained in place, but also welcomed new member states, therefore expanding to include many former “enemies” of the dissolved Warsaw Pact.

A renewed NATO and a much larger EU remain key players in the international system today, testifying to the enduring legacy of links and institutions created during the Cold War.

4. Conclusions

The last Soviet leader Michael Gorbachev had envisioned a reformed and more open Soviet Union that could have become part of a new pan-European structure, which he called the “common European home.” This inherently conveyed the idea of building close links between the Soviet Union and the then European Community in the transition to a post-Cold War era. Events proved Gorbachev wrong. The dissolution of the Soviet Union did not lead to a new European structure that included Russia (and the former Soviet republics). On the contrary, NATO expanded into the former Soviet space at a pace unforeseen and unexpected even in the West. Therefore, it can be argued that not only the Cold War but also the way in which the Cold War ended had a long-lasting negative impact on the Western world’s relationship with Russia.

The excessive facility with which contemporary observers revert to notions of a “new Cold War” not only reveals the continuation of an inherent Cold War mentality, but also the absence of a new structure to define the international system. However, the relevance of the Cold War today does not lie in simple, and often misguided, analogies. The international system today is radically different from the bipolar one, and the challenges to state security, increasingly rooted in non-state actors and transnational forces, are of drastically different nature compared to the – in many ways more simply defined – challenges of the Cold War era.

The relevance of the Cold War, instead, rests in concrete issues that continue to define the international system, such as nuclear weapons, problematic regional conflicts and the continued presence of transatlantic institutions, such as NATO and the European Union. These institutions have – over the decades – created a sense of common values and shared ideals. Even when interests have diverged, both within members of the European Union and between some European states and the United States, these transatlantic links have endured, testifying to a continued sense of belonging to a loosely defined “West” as different and distinct from the “the rest.” This, in itself, is another long-lasting legacy of the Cold War.

This paper is part of the History and Policy-Making Initiative, a joint research project led by the Geneva Centre for Security Policy (GCSP) and the International History Department of the Graduate Institute of International and Development Studies (IHEID) in Geneva.

Notes

[1] Henry Kissinger, Years of Renewal, London: Phoenix Press, 2000, p. 810.

[2] Excerpt from Winston Churchill’s so-called Iron Curtain speech, delivered on 5 March 1946 in Fulton, Missouri.

About the Author

Dr. Barbara Zanchetta is currently a Senior Researcher at the Graduate Institute of International and Development Studies in Geneva working in a research project called Reassessing the End of the Cold War funded by the Swiss National Science Foundation. She is specifically working on American foreign policy towards the Middle East during the last decade of the Cold War, and on a monograph provisionally titled The United States and the ‘Arc of Crisis’: American foreign policy, radical Islam and the end of the Cold War, 1979-1989.