The Rise and Stall of the Islamic State in Afghanistan

9 Nov 2016

By Casey Garret Johnson for United States Institute of Peace (USIP)

This article was external page originally published by the external page United States Institute of Peace (USIP) on 3 November 2016.

Summary

- The Islamic State’s Khorasan province (IS-K) is led by a core of former Tehrik-e-Taliban Pakistan commanders from Orakzai and Khyber Agencies of Pakistan; the majority of mid-level commanders are former Taliban from Nangarhar, with the rank and file a mixture of local Afghans, Pakistanis, and foreign jihadists mostly from Central Asia.

- IS-K receives funding from the Islamic State’s Central Command and is in contact with leadership in Iraq and Syria, but the setup and day-to-day operations of the Khorasan province have been less closely controlled than other Islamic State branches such as that in Libya.

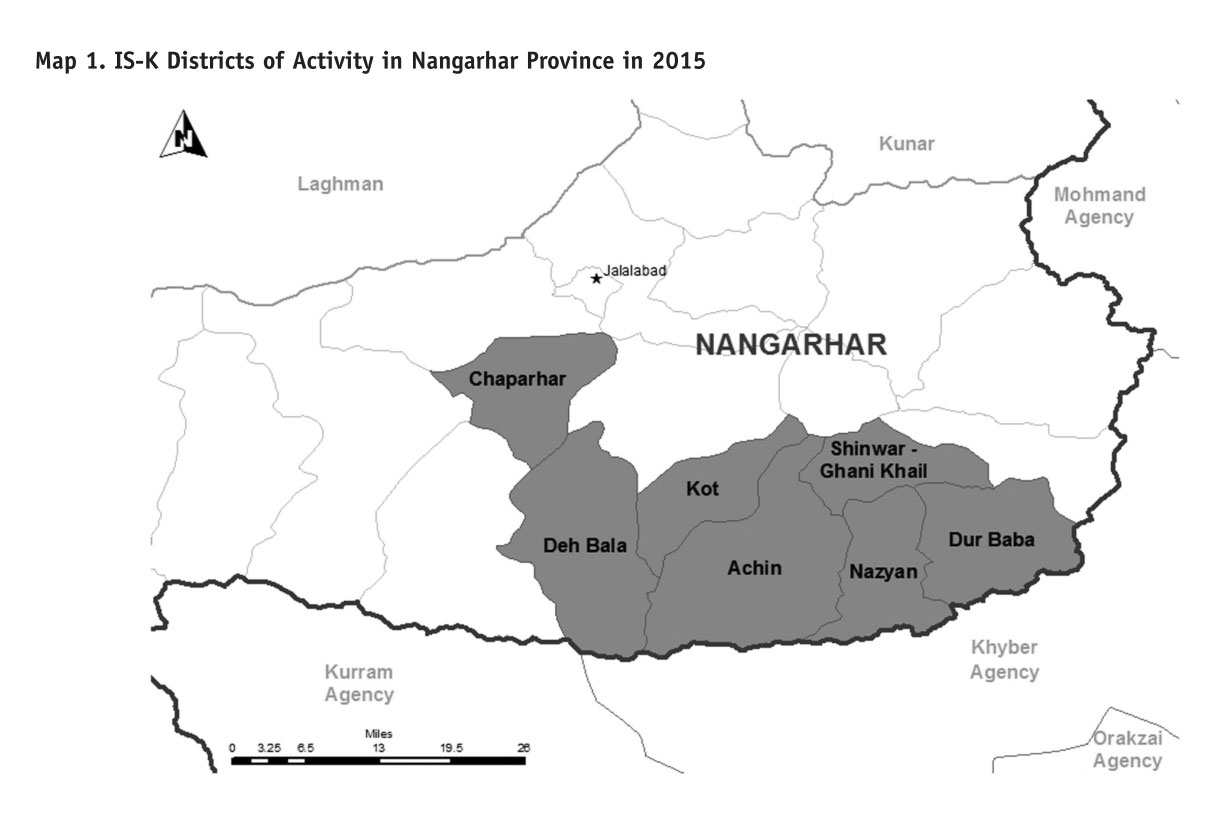

- IS-K emerged in two separate locations in Afghanistan in 2014—the far eastern reaches of Nangarhar province along the Afghanistan-Pakistan border, and Kajaki district of southern Helmand province.

- IS-K expanded in Nangarhar through the spring and summer of 2015, gaining partial control of seven districts by first remaining nonviolent and appealing to local Salafi networks and later entering into strategic alliances with cross-border militant networks. The Helmand front was quickly defeated by the Taliban.

- By the fall of 2015, IS-K grew more violent, announcing a ban on poppy cultivation and threatening aspects of the tribal social order; the limited public support in Nangarhar to erode.

- In early 2016, as IS-K leadership fractured into Pakistani and Afghan factions, the Taliban launched a counterattack that—along with U.S. air strikes and operations by private Afghan militias—stalled the IS-K advance.

- As of July 2016, IS-K was still present in a handful of Nangarhari districts and capable of launching spectacular attacks, including a suicide bombing in Kabul that killed more than eighty.

- There are few indications that the Islamic State is looking to shift its main effort to Khorasan if or when Mosul and Raqqa fall, however there are signs that IS-K is looking to strengthen its relationship to Islamic State Central, is seeking more assistance in the form of trainers, and is pressing for the return of Afghan nationals currently fighting for the Islamic State in the Levant to support operations along the Afghanistan-Pakistan border.

- The Taliban remain a greater threat to the Government of Afghanistan than IS-K. The government’s strategy of stepping aside as the Taliban and IS-K fight each other may have diminishing returns, particularly in places such as eastern Afghanistan where Taliban-Islamic State alliances of convenience could further undermine security.

Introduction

Since the Islamic State’s Khorasan province (IS-K) emerged in Afghanistan in 2014 it has struggled to expand beyond the handful of Afghanistan-Pakistan border districts in eastern Nangarhar where it first took root. Though IS-K has done a good job of recruiting disaffected low-level Taliban commanders from Nangarhar and a handful of militants from the Pakistan tribal areas, this local support remains just that—local. Though IS-K has appointed shadow governors and is recruiting in about a dozen Afghan provinces, its operations in these areas remain strictly limited. IS-K has stalled for a number of reasons: internal divisions between Pakistan and Afghan leadership; community rejection of, among other things, prohibitions on poppy cultivation and shrine worship; effective targeting by U.S.-led coalition air strikes; and fierce opposition by the Afghan Taliban—still the clear insurgent hegemon in Afghanistan and the chief threat to the Government of Afghanistan going forward. It remains to be seen if the recent death of IS-K’s Pakistani leader, Hafiz Saeed, will heal internal divisions, or if recent overtures by IS-K to Islamic State Central in Iraq and Syria for more training, support, and fighters will result in a resurgence.

This report provides an inside look at the Islamic State’s attempts to establish a foothold in Afghanistan through over sixty interviews with residents living in IS-K influenced areas of Nangarhar, as well as a number of Afghan security officials in Kabul during the spring and summer of 2016. Unless otherwise cited, statements and conclusions in this report are drawn from these interviews.

The Islamic State in Afghanistan

IS-K ’s Strength and Composition

Estimates of the number of IS-K fighters in Afghanistan vary widely. One analyst claimed in early February 2016 that IS-K strength in Afghanistan alone could be as high as 8,500 fighters and “support elements.”1 By contrast, the Pentagon estimated 1,000–3,000 fighters as of mid-February 2016, and Gen. John Nicholson, commander of U.S. and NATO forces in Afghanistan, estimated between 1,000–1,500 fighters as of late July.2 At the group’s height from August to December 2015, IS-K fighters numbered from 3,750–4,000, with almost all of these cadres active in eastern Nangarhar province, according to Afghan security officials and residents living in IS-K influenced areas. This number had been reduced to about 2,500 as of early March 2016. Fighters were a mixture of Afghan and Pakistan nationals, and other “out of area” foreign nationals. The majority of these out of area fighters are from Central Asia, including individuals associated with the Islamic Jihad Union, the Turkistan Islamic Party, and militants from as far away as Azerbaijan.

By contrast there are still relatively few Arab fighters. Additionally, while Afghans and Pakistanis have travelled to Syria and Iraq to fight for Sunni insurgent groups, returning fighters did not establish the Islamic State’s Khorasan province, nor do they currently constitute a significant number of the IS-K rank and file or leadership. However, Afghans fighting for the Islamic State in Syria and Iraq, many of whom were recruited not from Afghanistan but from Europe after having migrated there over the preceding decade, were beginning to arrive in small numbers in Afghanistan from Syria and Iraq in the summer of 2016, reportedly after requests by IS-K leaders for more support from Islamic State Central, according to Afghan intelligence officials. These returning fighters will likely serve as trainers and mid-level commanders rather than as rank-and-file fighters. IS-K and Islamic State Central increased communication throughout the summer of 2016, and included discussions about IS-K receiving Arab trainers in an effort to increase the capabilities of IS-K, though these had yet to arrive in any serious numbers as of mid-September 2016, according to Afghan security officials and residents living in IS-K influenced areas.

IS-K’s area of influence in Nangarhar had constricted from seven to three districts—Nazyan, Achin, and Deh Bala (also known as Haska Mina)—all border districts with access to safe havens in Khyber and Orakzai Agencies of Pakistan. Though IS-K has appointed shadow governors in the eastern Afghan provinces of Kunar, Laghman, and Logar, the number of fighters under their command in these provinces is difficult to determine and thought to be small. The largest presence among these three provinces is likely Kunar, where a combination of terrain, support networks, and access to both Pakistan and northern Afghanistan make it one of the most likely spots where IS-K could establish itself outside of Nangarhar. IS-K has appointed recruiters in nine other provinces, four of which (Kunduz, Samangan, Sar-e Pol, and Faryab) are located in northern Afghanistan—perhaps a telling allocation of resources, and an indication that IS-K’s strategy is to recruit outside of traditional Taliban areas of influence and move northward from their current base along the Afghanistan-Pakistan (Af-Pak) border through northern Afghanistan into Central Asia.

As of the summer of 2016, however, active IS-K presence in any of these nine provinces was strictly limited. The recruitment strategy in these areas is face-to-face outreach, education and preaching (dawah), and intelligence gathering—the same tactics the Islamic State used to expand into northern Syria from 2012 onward and that IS-K deployed during its first six months in Nangarhar. “[IS-K] recruiters are meeting with sympathetic Taliban commanders and communities in strategic areas, they are looking for people that are already armed and are promising them a regular paycheck,” said one security official tracking IS-K activities. “We think people are listening, and they may be organizing, but they aren’t active.” Among those that IS-K is organizing are reported to be “hundreds of women” recruited from May 2016 onward across at least seven eastern and northern provinces as well as Kabul province.

Senior Leadership

IS-K leadership is dominated by a core group of former Tehrik-e-Taliban Pakistan (TTP) commanders hailing from Orakzai Agency in Pakistan, including the recently deceased former wali (governor) of the Khorasan wilayat (province), Hafiz Saeed. A native of the Mamozai area of Orakzai Agency where he had formerly led TTP operations, Hafiz Saeed had been passed over for the Pakistani Taliban’s top spot, and was under pressure from the Pakistani military’s Operation Zarb-e-Azb, when he and five other commanders from Orakzai publicly renounced the Pakistani Taliban in October 2014.3 This group assumed IS-K leadership posts in a video released on January 11th, 2015, and Saeed remained its leader until his death from a U.S. drone strike in late July 2016.4 Islamic State Central had not officially announced a replacement as of mid-September; perhaps an indication that the terror group was concerned with not further widening the Afghan-Pakistani leadership rift that had opened during Saeed’s tenure.

IS-K’s number two, Shahidullah Shahid, is IS-K’s primary spokesman. He spent at least a decade in and out of Saudi Arabia, and is considered the main facilitator that linked the Islamic State to the Orakzai-based former TTP contingent that has dominated IS-K senior leadership thus far. Even when Hafiz Saeed was alive, several Afghan security officials said that Shahidul-lah Shahid was perhaps more influential due to his closer ties to Islamic State Central and to funding sources in the Gulf, and that his title of spokesman somewhat understated the role he plays. As of September 2016 Shahid was believed to be in the border areas of Nangarhar and Mohmand and Khyber Agencies of Pakistan.

IS-K’s leadership is notable for its lack of Afghans, even as the vast majority of its operations have occurred inside Afghanistan. This lack of parity among Afghan and Pakistani leadership, and the complex and longstanding international conflict between Afghanistan and Pakistan, continues to define IS-K. The highest ranking Afghan within IS-K was “deputy governor” Abdul Rauf Khadim of Helmand province. Khadim, a former Taliban regional commander and Guantanamo Bay detainee, held this post for only three days before he was killed in a U.S. drone strike, and his southern force was routed a month later.5

The absence of Afghan leadership is all the more significant given that the first and most vocal backer of the Islamic State in Afghanistan and Pakistan was Nangarhar native and former Guantanamo Bay detainee, Rahim Muslim Dost. Yet, when IS-K leadership positions were appointed in January 2015, Muslim Dost was given a relatively powerless seat on the IS-K leadership shura. Muslim Dost publicly broke with Hafiz Saeed in October 2015, declaring that Pakistani intelligence had hijacked IS-K in another ploy to keep its neighbor weak. In the same message, Muslim Dost reaffirmed his support to Islamic State leader Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi.6 Even following Hafiz Saeed’s death, Muslim Dost had yet to resurface as of mid-September 2016.

This split is significant for two reasons: First, though there is no evidence to back Muslim Dost’s allegation that Pakistan’s Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI) is controlling IS-K, the perception of such inside Nangarhar has eroded the limited support IS-K initially enjoyed—especially given that IS-K’s messaging in Nangarhar has focused heavily on driving home the point that the Taliban are nothing more than a puppet of the ISI, and no longer represent Afghans. By its very nature, the Islamic State “caliphate” seeks to erase the distinction between the nation states of Afghanistan and Pakistan; but as a recruitment strategy this is problematic, given the high level of distrust on both sides of the border. Ironically, the caliphate has found itself entangled in some of the very same Af-Pak nation state disputes that have plagued the U.S. and NATO for years.

Second, the phase of IS-K operations characterized by the execution of elders, the destruction of shrines, and prohibitions on growing opium poppy all coincided with growing control by Pakistani leadership—the Orakzai former TTP clique, but also militants loyal to Mangal Bagh, the leader of Lashkar-e-Islam, a for-hire militant organization and border smuggling network that controls the strategic Tirah Valley linking IS-K bases in Orakzai Agency with areas of operation in Nangarhar. Mangal Bagh, an Afridi tribesman from Pakistan’s Khyber Agency, conducts operations and recruits on both sides of the Af-Pak border, an area in which grievances and land conflicts provide steady support from marginalized communities. Mangal Bagh has been under pressure since Pakistan military forces launched operation “Khyber 1” against his network in March 2014, after which fighters and families loyal to Lashkar-e-Islam relocated from Khyber Agency to Nazyan district of Nangarhar province. According to one report, Mangal Bagh and his band of militants and their family members were welcomed by tribal elders on the Afghan side of the border and supported by the Afghan government, whose likely objective was to use Lashkar-e-Islam against Pakistan.7

Although Mangal Bagh has never publicly proclaimed allegiance to IS-K, many of his fighters are allied with IS-K, and Lashkar-e-Islam has served as an “implementing partner” for IS-K along the Af-Pak border. This support is largely the result of the need to control cross-border trade and safe havens vis-a-vis rival tribes inhabiting these same areas. Mangal Bagh’s son was reportedly killed in a U.S. drone strike in mid-January 2016 while fighting with IS-K forces in Achin.8 In late July, several Pakistani media outlets reported that Mangal Bagh also had been killed in a U.S. drone strike.9

Mid-level Leadership

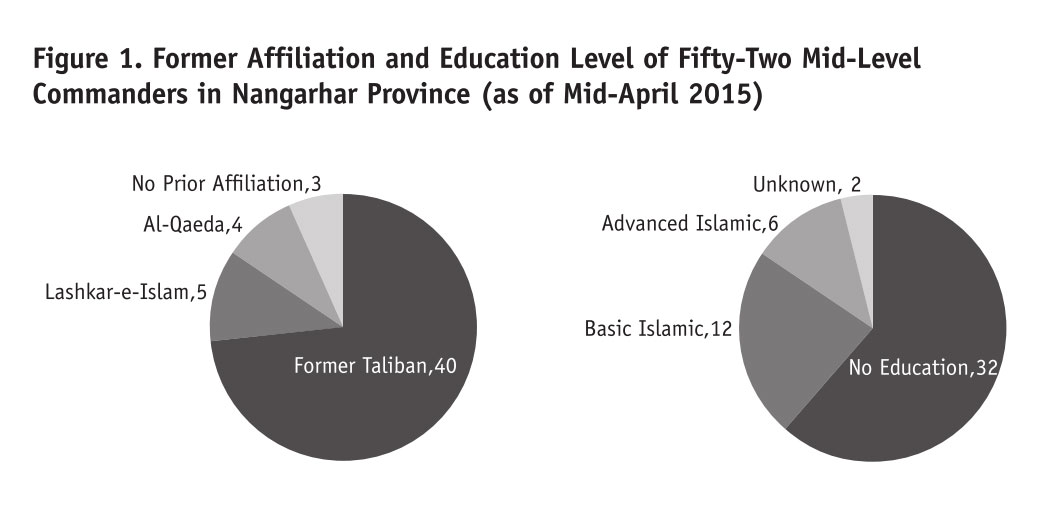

Through individual interviews with community members, former and current IS-K and Taliban members, and Afghan security officials, this report profiled fifty-two mid-level IS-K fighters from six districts of Nangarhar (see Figure 1). These individuals were either commanding small squads (10–20 men) within or near their districts of origin or had specialized positions, such as judge or bomb-maker.10 While upper-level leadership in IS-K is dominated by Pakistanis, mid-level leadership in Nangarhar is mostly composed of local former Taliban commanders.

Forty of the fifty-two commanders profiled were former Taliban commanders, five were former Lashkar-e-Islam militants, and four were former al-Qaeda affiliates. Only three had no prior affiliation.11 In many cases, former Taliban commanders who had joined IS-K were regarded as some of the more effective and notorious commanders in their areas; as one resident of Chaparhar district noted, “These are the guys who were already beheading people when Daesh [IS-K] showed up.” Of the thirty-three former Taliban commanders, twelve were known Salafis. Interviewees said that this affiliation was a significant factor, but only one among many motivations that were driving IS-K recruitment. Indeed, many commanders seemed to have switched allegiances for personal reasons—particularly to gain power and resources within their immediate communities; or simply because the rapid arrival of IS-K and the early ambivalence of Taliban leadership left them with no other choice but to join, especially if livelihood and familial obligations meant they could not flee.12 A majority of the former Taliban commanders had joined the Taliban only after 2009 and were not considered well-connected within the organization. The average age for all of the mid-level commanders profiled was estimated to be thirty-one years.

Thirty-two commanders had no formal schooling (in either madrassas or state primary schools), twelve had a basic Islamic education—either through a local mosque or madrassa—and six had an advanced Islamic education, with at least two of these studying at the Akora Khattak madrassa in Pakistan (a known point of radicalization). Thirty-eight of these commanders were still active as of June 2016; six had been killed in action in Nangarhar,13 and five were inactive. Three of the inactive fighters had joined a local pro-government militia.

A History of the Islamic State in “Khorasan”

Abu Musab al-Zarqawi in Afghanistan

Afghanistan and Pakistan served as host for many transnational terrorist organizations, including what would one day become the Islamic State. Abu Musab al-Zarqawi, a Jordanian who would become the future leader of the Islamic State in Iraq—the forerunner of the Islamic State—travelled to Afghanistan and Pakistan to fight alongside thousands of foreign fighters during the anti-Soviet jihad. A fellow militant who fought with Zarqawi in Afghanistan during the early 1990s described this first trip as formative: “Zarqawi arrived in Afghanistan as a zero.[…] It’s not so much what Zarqawi did in the jihad—it’s what the jihad did for him.”14 One of the things it did was provide a place for him to freely interact with doctrinaire Islamists—not just militant fighters, but militant thinkers. The most important of these was the radical cleric, Abu Mohammed al-Maqdisi, the chief ideologue for what would one day become the Islamic State.15

Back in Jordan, Zarqawi and Maqdisi’s attempts to foment jihad were quickly quashed and both were imprisoned from 1994 to 1999. After his release as part of a general amnesty in the spring of 1999, Zarqawi returned to Afghanistan. With the help of al-Qaeda leadership eager to gain influence in the Levant—an area where the terror organization still had relatively limited reach—Zarqawi was given a stipend and a plot of desert land in the western Afghan province of Herat where he founded the militant organization Jund al-Sham (Soldiers of the Levant). In December 2001, following U.S. air strikes, Zarqawi and about three hundred members of Jund al-Sham fled westward, seeking shelter first inside Iran and then finding refuge in northern Iraq. Here Zarqawi recreated his Afghan training camp and directed his focus on waging war against both the United States and Shia Muslims in the years to come. Zarqawi would never see Afghanistan again.

Afghanistan did not give rise to the Islamic State—the ideology, grievances, political and sectarian divisions and human resources that fueled it were, and continue to be, centered in the Middle East. Had he wanted, Zarqawi would have found it very difficult, even under the Taliban regime, to expand his small army outside the compound walls given his status as an outsider and the unreceptiveness of Afghans—even the Taliban—to his message. Yet, Afghanistan was critical. As a large, ungoverned space where paying guests were welcome—provided they followed the rules and did not challenge local authority—Afghanistan served as an incubator of sorts.

Though the nexus for transnational jihadism has shifted to Syria and Iraq in recent years, Afghanistan—and particularly the Af-Pak borderlands—remains a welcome place for many transient jihadists, particularly those with the resources to support one side of a local power struggle. Yet, the area remains hostile to external groups with visions of shaping the social landscape in their own image by, for instance, fomenting the kind of Sunni-Shia sectarianism that Afghanistan has mostly avoided throughout history, or subverting long-standing tribal norms regarding marriage, a pillar of Afghanistan’s socio-economic structure. This dynamic, more than the presence of the Afghan National Security Forces and their international military backers, explains why today’s Islamic State has gained a foothold and a measure of protection in Nangarhar but has found it difficult to expand this footprint.

A Former Detainee Becomes a Leader

On July 1, 2014, two days after self-proclaimed caliph Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi declared an Islamic State from the pulpit of a mosque in Mosul, Iraq, Rahim Muslim Dost became the first Afghan to publicly offer his bay’a (allegiance) to the caliphate. Though a handful of al-Qaeda militants from Yemen and Saudi Arabia hiding out along the Af-Pak border had publicly voiced support for the Islamic State months earlier,16 it was not until Muslim Dost’s pronouncement, and the subsequent appearance in early September of a booklet known as Fata (victory) advocating the establishment by force of an Islamic caliphate in Nangarhar and Kunar provinces, that the Islamic State became a reality in Afghanistan.

A native of Kot district in Nangarhar province, Muslim Dost, like many of his era, grew up across the border in Peshawar, Pakistan where he served as the communications director of a Salafist mujahideen party, Jama’at al Da’wa al Qur’an (Society for the Call to the Quran), during the anti-Soviet jihad of the 1980s. Despite not being a member of the Taliban, in late 2001 or early 2002 Muslim Dost was detained in Pakistan and eventually handed over to the United States and subsequently detained at Guantanamo Bay until the spring of 2005 when he was released and disappeared back to the Af-Pak borderlands where he recited poetry at packed readings but never joined the Taliban-led insurgency.

Throughout the fall of 2014, IS-K’s outreach strategy relied heavily on face-to-face interaction with Salafi families in seven or eight districts of southeastern Nangarhar, with Muslim Dost and a handful of former Taliban insurgents and sympathetic clerics conducting dawah (preaching) in houses and mosques.17 Salafism, which is relatively new to Afghanistan, emerged as a school of thought in the 19th century from the center of Sunni learning, Al-Azhar University in Egypt. Salafis believe in a return to the practice and interpretation of Islam as it existed during the time of the Prophet Mohammed. Though the Islamic State and other jihadist and terror organizations have used Salafist ideology to justify their actions, the vast majority of Salafis are nonviolent and have recently sought, in countries like Tunisia and Egypt, to participate in mainstream party politics.18

In Nangarhar, Salafis represent just a fraction of the population. Of the seven Nangarhari districts where interviews were conducted for this study, Salafis often numbered no more than 20–30 families, or less than 5 percent of the total population, according to rough estimates by district residents. Although backing from segments of the local Salafi community provided a necessary entry point, the mere presence of Salafis cannot, and the appeal of ideological narratives does not, fully explain how IS-K took root in Nangarhar, much less how it expanded. In fact, IS-K’s growth throughout late 2014 and early 2015 was less the result of active support than an absence of resistance, which was driven by a number of factors.

First, IS-K was less of a burden on local communities than the Taliban had been. IS-K provided its own food, via Pakistan, or purchased it off local markets, often at prices exceeding the market rate as a means of ingratiating themselves. IS-K did not demand taxes and, initially, allowed both boys’ and girls’ schools to remain open. The group was less extortive of local families and tribes than the Taliban had long been. This would change dramatically from about mid-2015 onward; but in this early period, IS-K was generally seen as positive for the economy and respectful of locals.

Second, IS-K benefitted from high levels of violent rhetoric and attitudes, if not always from violent actions, already present in Nangarhar. As a civil society activist recounted:

Daesh came into our areas with guns and loudspeakers shouting against the Taliban. But there were some nonviolent Islamic associations that had been giving similar speeches—talking about the incompatibility of democracy and Islam and supporting the formation of a caliphate. So we were a bit confused. Even at Nangarhar University, professors are teaching their students some of the same things that ISIS was saying in the first months that it arrived.

Third, while the security situation in Nangarhar had been declining steadily for about two years when IS-K first appeared, the insurgent landscape was also extremely fractured.

Though fighting under the Taliban banner, a closer look revealed a mix of armed groups with competing loyalties and ties to, among others, Hizb-e-Islami Gulbuddin; cross-border militant organizations like Lashkar-e-Islam and the TTP, which had relocated to Afghanistan en masse with their family members in 2014 following Pakistani military offensives; and a number of smaller groups operating as for-hire kidnapping/extortion/road bandit networks over which the Taliban had little effective control. The Taliban, known locally as the Emirate Islami, were present; but the control of Quetta Shura has been notoriously weaker in Nangarhar than, say, Kandahar, Uruzgan, and Helmand, the Taliban’s heartland and the birthplace of the vast majority of the group’s core leadership.19 This fractured landscape provided a more fertile ground for the Islamic State than in other areas of Afghanistan where Taliban authority, and particularly the Quetta Shura, was stronger.

On the other hand, government control was confined to no more than 20 percent of any of the districts where IS-K focused its initial outreach. The government often held only a small area around district centers and a few checkpoints along main arterial roads. Yet, even when IS-K began to gain enough strength to carry out offensive operations in the spring of 2015, they refrained from targeting Afghan security forces—a strategy that kept the Afghan army and police out of the villages, limiting civilian casualties, and allowing IS-K to focus its efforts on confronting the Taliban and intimidating local tribal and religious leaders. “Daesh was telling people that they don’t have any conflict with government officials or the com-mon people,” a resident from Kot district explained.

Because they were pointedly ignoring Afghan security forces and government officials, rumors began to spread that IS-K was in fact a government creation meant to deal with the Taliban. A July 2016 report by the Afghanistan Analysts Network claims that Afghanistan’s intelligence agency, the National Directorate of Security, has supported the militant organization Lashkar-e-Islam and elements of TTP since 2014 with the aim of playing these militants against Pakistan in retaliation for Pakistan’s longtime support of the Afghan Taliban. However, segments of the TTP subsequently pledged allegiance to IS-K and were rewarded with leadership positions by the Islamic State, while in 2015 Lashkar-e-Islam entered into a strategic, though unofficial, alliance with IS-K.20 Rumors surrounding IS-K’s external sources of support would flip in the latter half of 2015: IS-K was the creation of Pakistani intelligence, as a means of redirecting segments of the TTP across the border with the ultimate goal of keeping the government of Afghanistan weak, especially along the Durand Line. This narrative was spread by both the Taliban and the Afghan government, according to those interviewed for this report.

These shifting narratives were perhaps not surprising, given that Afghan security officials later admitted they were looking the other way as the Taliban, which had belatedly grasped the threat that IS-K posed to their operations in Nangarhar, moved fighters and arms into western Nangarhar from the summer of 2015 onward to confront IS-K.

Meanwhile in Helmand

About five hundred miles southwest of Nangarhar in the Taliban heartland of Helmand province, a parallel effort to establish an Islamic State front was being led by another former Guantanamo Bay detainee, Abdul Rauf Khadim. Unlike Muslim Dost, Khadim was a battle-hardened military commander long associated with the Taliban. In the late 1990s he served in an elite mobile reserve unit, leading Taliban fighters against regime opponents and eventually surrendering to Northern Alliance leader Abdul Rashid Dostum’s forces in the fall of 2001.21 Records show he arrived at Guantanamo Bay on February 10, 2002.22 Throughout his detention, Khadim maintained he was merely a foot soldier and errand runner for front-line troops in Kunduz province.23 In December 2007 he was released from Guantanamo Bay into Afghan custody and soon fled house arrest in Kabul, going first to Pakistan and then to his native Kajaki district of northern Helmand sometime in 2009.

When he reappeared in Kajaki, associates say, he was the same gruff commander, but his ideology had shifted to a radical form of Salafism. “We knew his thinking had changed in Guantanamo,” a family member said, “because the first thing he did when he came home was destroy the shrine in Kajaki to his brother,” a Taliban commander and local hero. Salafism prohibits shrine worship, and the destruction of Shia and Sufi shrines in Iraq, Syria, and Afghanistan has become an Islamic State trademark.

Taliban leaders also understood that Khadim’s beliefs had changed, but were unwilling to sideline an effective commander and former Guantanamo Bay detainee, a distinction that serves as a powerful recruiting tool. Instead, the Taliban embarked on their own form of deradicalization: first dispatching their own Islamic scholars to engage Khadim in debate, then attempting to bring him further into the fold with high-level appointments in the insurgency shadow government. Khadim accepted these appointments while quietly converting his children, close friends, and sub-commanders to Jihadi Salafism—a dangerous task in a part of the country with far fewer Salafis than Nangarhar. “He knew he couldn’t act publicly on his views because the community wouldn’t have supported him and the Taliban would have crushed him, so he spent about three or four years building the community himself,” an associate explained.

In April 2014, Khadim’s fellow tribesman and the head of the Taliban’s military commission, Abdul Qayum Zakir, was publicly fired by Akhtar Mansour (then the Taliban’s second in command and, from July 2015 until his death from a U.S. drone strike in May 2016, the leader of the Taliban). Afghan security officials believe that Zakir encouraged Khadim to break away and may have made promises of eventual support. Sometime after Zakir was sacked, Khadim is believed to have travelled to Iraq, on a fake passport obtained in Pakistan, where he met with representatives of the Islamic State. When he returned to Kajaki, residents say Khadim’s sub-commanders were suddenly and conspicuously flush with cash. Around this time, the Nangarhari IS-K recruiter Rahim Muslim Dost was spotted in Zamindawar, an opium bazaar in Khadim’s home district of Kajaki.24

Emboldened and well-financed, Khadim’s cell of about three hundred armed men—until that time considered loyal Taliban—activated in January 2015, first beating a local mullah accused of issuing ta’wiz,25 then killing a Taliban commander, and later capturing and executing Afghan National Army soldiers without the usual pretense of a trial in the local Taliban court. Khadim’s men began to fly black and white banners—though it is unclear if these were specifically Islamic State flags or one of any number of similar black and white jihadist emblazoned flags.26 “Northern Helmand was originally designed as the starting point for IS,” maintains an Afghan security official who was tracking Khadim during this period. Whether or not this is the case, the Islamic State recognized its importance, appointing Khadim deputy governor of its Khorasan province in January 2015.27

The Taliban also recognized Khadim’s importance. While the Quetta Shura had largely ignored IS-K recruitment in Nangarhar throughout 2014, they saw the situation in Helmand as an immediate threat. Not only was the Islamic State recruiting in the Taliban’s back yard, their arrival threatened to further divide the movement—particularly if the disgruntled commander Abdul Qayum Zakir was to join forces with Khadim, taking with him thousands of fighters and jeopardizing the Quetta Shura’s control of lucrative opium bazaars in northern Helmand’s Kajaki and Sangin districts.

Though the Taliban refused to publicly admit that the Islamic State could be active in Helmand or that one of their top commanders had defected, Taliban fighters clashed with Khadim’s men in late January and early February, isolating the IS-K front and inflicting heavy casualties. On February 9, Khadim was killed in a U.S. drone strike while travelling by road between Zamindawar and neighboring Musa Qala district.28 Following his death, Khadim’s family and sub-commanders fled westward to neighboring Farah province, where they again came under attack by the Taliban in Khak-e-Safid district. Remaining fighters and family fled northward from Farah into mountainous Ghor province in Afghanistan’s central highlands or to Pakistan. Abdul Qayum Zakir reconciled with Akhtar Mansour before Mansour’s death, and the Taliban’s position in Helmand is today arguably stronger than any time since 2001.

IS-K’s rise and fall in Helmand demonstrates how important logistics and access are to the group’s success. In northern Helmand, Khadim’s front was surrounded by Taliban and Taliban-supporting communities, which blocked supply routes and access to safe havens across the border in Pakistan. This not only limited the group’s ability to hold territory, it also discouraged any large-scale defections among mid-level Taliban commanders here, despite significant divisions within the movement.

The Taliban Retreat

As IS-K was being routed in Helmand, their efforts in Nangarhar were ramping up. Following the appointment of a handful of TTP commanders from Pakistan’s Orakzai Agency to the top of the IS-K hierarchy in January 2015, the phase of quiet outreach gave way to an overt show of force and direct confrontation with both the Taliban and tribal communities.

The first place in Nangarhar that IS-K began to fly its black flags, in January of 2015, was the Mamand area of Achin district. Achin borders the Tirah Valley of Pakistan, a strategic entry-exit corridor along the mountainous border. The shift in strategy from quiet preaching to a show of force was in some cases met with resistance. When a district resident arrived in Achin from Pakistan with one hundred fighters and announced his intention to fight for the Islamic State, a tribal council (jirga) decreed that his house be burned, and the commander and his men fled.29 By early February, however, Islamic State flags were flying from the roofs of houses in about seven southeastern Nangarhar districts. In April, IS-K cadres also began to appear in neighboring Logar province, signaling their presence by attacking several Sufi shrines and establishing a training base.30

The Taliban appeared to be caught off guard. Throughout January and February, Taliban senior leadership seemed to be assessing the danger that IS-K posed. In March, IS-K began to attack Taliban forces in several districts; in Kot district, IS-K and local Taliban forces clashed in an area known as Pata Dara, with casualties on both sides. Taliban fighters from Kot describe increasingly frantic attempts to reach the Quetta Shura. With no guidance from Quetta forth-coming, district-level Taliban commanders travelled across the border to Mohmand Agency in Pakistan in mid-March, looking for instructions from the Peshawar Shura. Representatives from the Shura allegedly explained that talks between IS-K and Afghan Taliban leadership were ongoing. By April, these talks had failed and Quetta issued orders for Taliban cadres to attack IS-K; but by this time, IS-K had built a strong enough base of support that the Taliban had to retreat from Kot, Achin, Nazyan, and Deh Bala districts westward to Khogiani district, where they began to regroup. Apart from sporadic attacks, the Taliban did not begin a serious counter-offensive until December 2015.

In contrast, IS-K continued to ignore the Afghanistan National Security Forces who maintained a static and reactionary presence along arterial roads and around district centers. Whether this signaled a deliberate strategy or the absence of one, IS-K was allowed to take root at the village level and establish cross-border resupply into Pakistan unhindered.31 This scenario seems to follow the Islamic State’s advance into northern Syria in 2013 and 2014, when the group went after local jihadist rivals (primarily the al Nusra Front) and mostly refrained from attacking Assad regime forces.

From Preaching to Killing

With the Taliban gone and the Afghanistan National Security Forces a nonentity, IS-K began a campaign to expand and consolidate control through the execution of summary justice, forced displacement, and targeted killings. IS-K executed at least six clerics and six elders from the Kot district alone from April 2015 to January 2016. Another five clerics based in Jalalabad city were killed from mid-2015 onward for failing to support IS-K either from the pulpit or by providing fighters from among their congregations or religious student body. In August, ten tribal leaders accused of providing support to the Taliban were bound, blindfolded, led past Islamic State flags by masked gunmen, and forced to kneel atop a daisy chain of IEDs.32 The video of their death went viral. Interviewees say that many of the executions carried out in the spring and summer of 2015 were strategic in nature—but many others appeared to be the settling of old scores and local disputes by Islamic State partisans now in the position to take revenge.

In this environment of heightened violence and shifting power, short-range displacement became a fact of life. Families and religious leaders not aligned with IS-K relocated to the provincial capital of Jalalabad or into Taliban-controlled areas in western Nangarhar such as Khogiani district. IS-K partisans arrived from surrounding districts, Jalalabad city, and other provinces of Afghanistan like Kunduz and Helmand. In Kot, for instance, madrassas affiliated with the Panjpiri school of thought were directed to surrender their students for induction into Islamic State—some complied, but many others refused and closed their doors indefinitely as madrassa teachers relocated to Jalalabad city.

Throughout the summer, IS-K’s ranks grew as they recruited from both the Afghan and Pakistani Taliban; the latter group had been under increasing pressure from the Pakistani military’s Zarb-e-Azb counterinsurgency campaign in the Federally Administered Tribal Areas and, like the Afghan Taliban, were looking to gain control in local power struggles within their communities and within their insurgency. IS-K also successfully co-opted the cross-border criminal/militant network Lashkar-e-Islam, which operates along the Nangarhar province-Khyber Agency border area. Lashkar-e-Islam was already involved in several land conflicts straddling the Af-Pak border; by partnering with IS-K, it was able to increase its influence on these conflicts and gain more control of strategic smuggling routes. In return, IS-K was able to broaden its support base and increase its operational capacity.

On the other side, Afghan militias—considered pro-government but often fighting for narrow territorial interests—began to mobilize in the absence of Taliban and more formal government security force intervention. Recruiting and outreach was further augmented by an IS-K FM radio station, “The Voice of the Caliphate,” broadcasting throughout the province. (Although an airstrike disabled the radio for several months in early 2016, it was back on the air as of May and broadcasting throughout the province daily in four languages: Pashtu, Dari, Pashai, and Arabic.)

The Taliban Counterattack

Throughout the late summer and fall of 2015, the Quetta Shura responded by sending Taliban fighters and materiel from across the country to Nangarhar, staging primarily in Khogiani district. In October, U.S. forces began air strikes against suspected IS-K fighters, even as Afghan security forces, still mostly unmolested by IS-K forces, seemed content to watch what looked to be an impending Taliban offensive against IS-K.

By the early fall of 2015, local perception of IS-K had shifted significantly. Though segments of the community had welcomed the presence of the group in its nonviolent proselytizing form and appreciated the fact that armed IS-K cadres did not make onerous demands on villagers for food and taxes like the Taliban had long done, these early benefits gave way as IS-K executed tribal elders and announced that it would ban poppy cultivation—an important livelihood in Nangarhar—at a time when market prices and yields were expected to be high.33 IS-K also began to conduct kidnapping-for-ransom operations—holding tribal leaders, businessmen, and cell tower security guards hostage and demanding money and/or ammunition and weapons in return for their release. Additionally, while the Islamic State touted their form of justice as true to Islamic sharia and superior to that of the Taliban, communities witnessed brutal, summary punishments executed outside the Islamic sharia they understood.34

Beyond these security and economic consequences, communities began to object to the religious and social strictures of life under the Islamic State—namely the destruction of dozens of Sufi shrines in several districts and the promise that IS-K fighters would be provided brides from among the local communities. Though rumors of such marriages remained just that, the threat that IS-K cadres would be given wives without paying dowries or in consideration of tribe and family lineage so threatened the social (and economic) fabric of the com-munity as to drive support for a return of the Taliban.

As the limited public support waned and the poppy season approached, Taliban forces dis-patched to Nangarhar from throughout Afghanistan during the summer and fall of 2015 began to launch counter-offensives into Chaparhar and Kot districts from bases in Khogiani in late 2015. From December 2015 through the end of February 2016, the combination of large-scale Taliban offensives, ad hoc community uprisings, the selective engagement of Afghan security forces and pro-government militias, and what locals described as “very effective” U.S. drone strikes, IS-K’s territorial expansion was halted and it abandoned the districts of Chaparhar and Kot to the Taliban and Afghan government.35 Among these disparate forces, community members consistently singled out the Taliban as the main reason for the decline and/or expulsion of IS-K in their areas. In addition to protecting opium poppy cultivation, the Taliban gained support from communities by promising to halt the destruction of shrines and to prevent IS-K from interceding in a number of active land conflicts. The Taliban has, for the time being, also adopted a more lenient attitude vis-à-vis community members with relatives serving in the Afghan National Army or Police.

In early March 2016, IS-K fighters and their families were retreating through the Nangarhar border districts of Nazyan and Achin, down the Tirah Valley into Pakistan’s Khyber Agency, with some falling back as far east as Orakzai Agency, the home of IS-K senior commanders and the alleged location of IS-K’s leadership shura.36 Though the composition of this group was unclear, those interviewed said it was a combination of previously displaced Pakistani fighters and their families associated with the TTP and Lashkar-e-Islam and now aligned IS-K as well as Afghan fighters and their families. Though Afghan President Ashraf Ghani told the Afghan Parliament in early March that IS-K had been defeated in eastern Afghanistan,37 residents of Achin and Nazyan districts said IS-K fighters were flowing back up the Tirah Valley into Nangarhar from Khyber Agency by the end of March.

IS-K continued to hold positions and operate rudimentary detention centers, mostly holding Taliban prisoners, in Achin and Deh Bala districts. It was from Achin and Deh Bala, as well as cross-border sanctuaries in Pakistan, that IS-K launched a large offensive against Afghan security forces in central Nangarhar in late June. One Afghan intelligence official estimated that 600 IS-K fighters were involved in the attack, and the governor of Nangarhar claimed that 131 had been killed in U.S. air strikes and ground combat with Afghan security forces.38 Other security sources maintain that an unknown number of IS-K cadres had shifted northward to mountainous Kunar province, though whether Kunar was expected to be a new front or simply a place of refuge was uncertain.

On July 23, the Islamic State claimed responsibility for a suicide attack on a gathering of mostly Shia demonstrators from Afghanistan’s Hazara ethnic group in central Kabul, killing at least 80 and wounding 231.39 This was the first significant IS-K attack outside of Nangarhar and the first time the group managed to attack Afghanistan’s Shia population. Though targeting Shia is a cornerstone of the Islamic State’s ideology and a key component of their operations in Iraq, the Khorasan branch has focused its attacks on fellow Sunnis aligned with the Taliban, first because the Taliban represented the greatest existential threat and secondly because there are essentially no Shias near IS-K’s areas of control along the Af-Pak border in Nangarhar. Though the attack was successful in that it demonstrated that IS-K could reach outside its areas of immediate control, attacking Shia may have far less strategic value than in Iraq given the absence of strong Sunni-Shia sectarian divisions within Afghanistan’s political power structures.

As July came to a close and this report was being prepared for print, Afghan and U.S. special forces had launched a new offensive along the Af-Pak border in Nangarhar, and reports began to circulate that the Taliban and the Islamic State had forged an informal alliance in eastern Afghanistan.40

Conclusion and Policy Considerations

The need to exploit cross-border insecurity will make it difficult for IS-K to expand further into Afghanistan, as demonstrated by the group’s failure to establish a foothold in northern Helmand in 2015. Other factors—including the absence of meaningful sectarian divisions, a pervasive mistrust of outsiders, and the presence of the Afghan Taliban as the clear militant hegemon—will make a rapid Iraq- or even Syria-like expansion by the Islamic State in Afghanistan unlikely.

Although IS-K strength is exaggerated, its propaganda effect should not be underestimated. The primary role of the Islamic State’s Khorasan province in the near term is that of propaganda tool. Indeed, both the Government of Afghanistan and the Islamic State have an interest in playing up the threat of IS-K as a means of garnering international support: in the former case, to ensure that international military and aid continues to flow into the country as interest has shifted westward to the Levant and North Africa, and for the latter as a general recruiting tool—a means of burnishing its jihadist bona fides in an area with historical significance to transnational jihadism.

The same factors that enable the Taliban will also allow IS-K to fester. Even taking into account structural obstacles and the group’s limited aspirations in the region, IS-K will remain problematic in the near term for a number of reasons: first, the group appears to be well-funded, obtaining significant sums from Islamic State Central routed through diverse channels (the Gulf, China, Turkey) and prioritizing control of areas inside Afghanistan where it can extract revenue from the control of heroin processing and trading, timber smuggling, and kidnapping.41 IS-K’s position along the Af-Pak border is crucial to the flow of external funding from abroad through Pakistan and into Afghanistan, as well as its internal revenue streams which depend upon a porous international border. If displaced, the group will likely seek out another area along the border—most likely northwards into Kunar or even Badakshan.

A regionally supported political settlement with the Taliban should continue to be a focus. Establishing border security will be key to any serious attempt at rooting out IS-K. Yet the governments of both Afghanistan and Pakistan appear willing to sacrifice long-term regional security to enable their own—ultimately uncontrollable—militant proxies to create insecurity for their neighbor across the Durand Line. As long as these shortsighted tactics are not reversed, international forces, and the international community more broadly, risk getting drawn into a fight with the Islamic State that is essentially the same mix of territorial, regional-geopolitical, and hyper-local conflicts that have characterized Afghanistan-Pakistan relations for decades. The fight against IS-K, while important, is a distraction from the main line of effort: peace and stability through a regionally supported political settlement with the Afghan Taliban.

The Taliban have benefited from the rise of IS-K. The Islamic State emerged at a time of uncertainty for the Taliban as rumors, and then confirmation, of the death of leader Mullah Mohammed Omar threatened to divide the group. Though many mid-level commanders in Nangarhar have indeed defected, mass defections and splintering of the Taliban movement have yet to occur. Instead, IS-K’s presence has been a net positive to the Taliban in both Nangarhar and Helmand, where the group has consolidated control and played the role of “true Afghan” community protectors.

It’s not just the Islamic State. More alarming than the presence of the Islamic State is the rise in the number of external groups now active in Afghanistan—including the Tehrik-e-Taliban Pakistan, other border-dwelling militant organizations like Lashkar-e-Islam that have relocated into Afghanistan, and Central Asian jihadists that have been relocating from the Federally Administered Tribal Areas for years. The presence of these groups—many of whom have sectarian agendas—more so than just the Islamic State may further alter conflict dynamics in Afghanistan. On the other hand, the rise of anti-IS-K militias linked to local powerbrokers, Taliban breakaway factions supported by the National Directorate of Security, and increasing involvement by Iranian intelligence throughout Afghanistan are creating an even more complicated picture. If they often provide immediate offensive capabilities against IS-K, they will continue to frustrate the Government of Afghanistan’s efforts to establish rule of law and a monopoly on the use of violence in the medium- and long-term.

Notes

1. Antonio Guistozzi, “The Islamic State in Khorasan: A Nuanced View,” RUSI, February 5, 2016, https://rusi.org/commentary/islamic-state-khorasan-nuanced-view. This same report estimates there are two thousand to three thousand IS-K cadres in Pakistan.

2. Tim Craig, “The Top U.S. Commander in Afghanistan is Leaving, but the Troops Are Staying,” The Washington Post, February 13, 2015, www.washingtonpost.com/world/top-us-commander-in-afghanistan-is-leavingbut-the-troops-are-staying/2016/02/13/790224e4-d271-11e5-90d3-34c2c42653ac_story.html; and “Five Troops Wounded in Combat with ISIS in Afghanistan,” The Associated Press, July 28, 2016.

3. After the death of TTP leader Hakimullah Mehsud in November 2013, Hafiz Saeed was one of four commanders short-listed to take control of the organization. Maulana Fazlullah, a native of Swat, was eventually promoted to the top spot but has spent the majority of his tenure on the run from successful Pakistani operations and has failed to heal any of the major geographical and tribal leadership rifts that have long plagued the TTP. Current splits in the Tehrik-e-Taliban date to the death of former leader Hakimullah Mehsud in a drone strike in November 2013, but other analysts point out that the TTP has been divided, at least more so than the Afghan Taliban, since its founding in 2007. By all accounts, Saeed was an effective and ruthless insurgent who oversaw a disciplined, tribally organized force and was believed to have planned and overseen a string of high profile attacks on sectarian, tribal, international, and state targets from 2008 to 2013.

4. “ISIS’s Leader in Pakistan and Afghanistan Killed in U.S. Drone Strike” Reuters, August 12, 2016, www.theguardian.com/world/2016/aug/12/isis-leader-pakistan-afghanistan-hafiz-saeed-khan-killed.

5. Khadim was recognized as deputy governor of Khorasan at the same time as Hafiz Saeed was announced as governor and was memorialized in an obituary a month later. Rabi Al Akhir, Dabiq 7, (2015): 33-35; and Jumada al-Akirah, Dabiq, 8 (2015): 30-32, http://jihadology.net/2015/03/30/al-?ayat-mediacenter-presents-a-new-issue-of-the-islamic-states-magazine-dabiq-8/.

6. October 17, 2015, http://rohi.af/fullstory.php?id=41196.

7. Borhan Osman, “The Islamic State in Khorasan: How it Began and Where it Stands Now in Nangarhar,” Afghanistan Analysts Network, July 27, 2016, www.afghanistan-analysts.org/the-islamic-state-in-khorasan-how-it-began-andwhere-it-stands-now-in-nangarhar/.

8. “Mangal Bagh Group Gaining Strength in Nangarhar,” Pajhwok Afghan News, January 19, 2016, www.pajhwok.com/en/2016/01/19/mangal-bagh-group-gaining-strength-nangarhar.

9. “Laskhar-e-Islam Chief Mangal Bagh Killed in a Drone Strike,” Pakistan Today, July 24, 2016, www.pakistantoday.com.pk/2016/07/24/national/lashkar-e-islam-chief-mangal-bagh-killed-in-us-drone-strike/.

10. These commander profiles were triangulated through a third research team working separately but concurrently in the survey area, as well as with historic data on insurgent commanders and networks compiled by The Liaison Office, an Afghan research organization, from 2007 to 2015. District breakdown: (9) Achin, (13) Bati Kot, (10) Kot, (6) Chaprahar, (10) Deh Bala, (4) Nazyan.

11. Many had multiple affiliations—for instance, three of the Lashkar Islam militants had also fought with the Taliban and three of the Qaeda members had similarly fought with the Taliban; their affiliation listed here was for the communities considered their primary or most known affiliation.

12. These mixed motives are evident in the top IS-K commander in Nangarhar, as of April 2016, Abdul Khaliq. A Nangarhar native who has been affiliated with al-Qaeda in Pakistan and the Afghan Taliban and ran afoul of the Quetta Shura when he took a group of election workers hostage and killed an unknown number of local elders in 2014. In order to escape what amounts to a Taliban arrest warrant he fled to the Tirah Valley just across the border from Nangarhar in Khyber Agency, returning to Afghanistan with one of the first contingents of IS-K fighters from the Tirah Valley in December 2014. The other significant IS-K commander in Nangarhar is Mullah Torfan, an Afghan native who has lived mostly in Orakzai Agency of Pakistan where he was previously a TTP commander.

13. The most recent IS-K commander profiled here to be killed in action was Mullah Barzag, a native of Kot district, targeted in an air strike in early June. “ISIS Commander Mullah Bozorg Killed with His 5 Fighters in Nangarhar,” Khaama Press, June 8, 2016, www.khaama.com/isis-commander-mullah-bozorg-killed-with-his-5-fighters-innangarhar-01207.

14. Joby Warrick, Black Flags: The Rise of ISIS (New York: Doubleday, 2015), 17-22, 53; and Mary Anne Weaver, “The Short Violent Life of Abu Musab al-Zarqawi,” The Atlantic, June 8, 2006, www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2006/07/the-short-violent-life-of-abu-musab-al-zarqawi/304983/. Al Zarqawi was in the Af-Pak borderlands from 1989 to 1993. Though the Soviet army had left Afghanistan by the time he arrived, Zarqawi saw significant fighting in Khost and Paktia provinces of southeastern Afghanistan.

15. A 2006 study by the Combatting Terrorism Center listed al Maqdisi as the most influential living jihadist. As the CTC’s study notes, both terms—Jihadist and Salafi—are problematic for a number of reasons. Salafis are Sunni Muslims who want to establish and govern Islamic states based solely on the Koran and the examples of the Prophet during the period in which he lived. Essentially a fundamentalist and literalist interpretation of Islam with no room for “culture” as such, nor any tolerance for practices not strictly adhering to those carried out during the time of the Prophet. The vast majority of Salafis are nonviolent and/or apolitical and involved in quietist preaching and outreach. Many jihadists, literally holy warriors, draw the legitimacy for their violent acts from the same traditions and doctrines as Salafis and so can be seen as a violent component of the much larger, nonviolent, Salafi movement. Al Maqdisi split with Zarqawi in 2004 due to his (Zarqawi’s) attacks on Shia Muslims in Iraq. “Militant Ideology Atlas, November 2006,” Combatting Terrorism Center, www.ctc.usma.edu//wp-content/uploads/2012/04/Atlas-ExecutiveReport.pdf.

16. Don Rassler, “Situating the Emergence of the Islamic State of Khorasan,” Combating Terrorism Center, March 19, 2015, www.ctc.usma.edu/posts/situating-the-emergence-of-the-islamic-state-of-khorasan.

17. Thomas Jocelyn, “Ex Gitmo ‘Poet’ Now Recruiting for the Islamic State in Pakistan and Afghanistan,” The Long War Journal, November 16, 2014, www.longwarjournal.org/archives/2014/11/ex-gitmo_poet_now_re.php.

18. For more on the origins, similarities, and differences of Salafism and Wahhabism, see Hamid M. Khan, “Islamic Law Practitioners Guide,” International Network to Promote the Rule of Law, 45-47, http://inprol.org/publications/12470/inprol-islamic-law-guide.

19. Michael Semple, “Rhetoric, Ideology, and Organization Structure of the Taliban Movement,” Peaceworks no. 102 (Washington, DC: U.S. Institute of Peace, 2014).

20. Osman Borhan, “The Islamic State in Khorasan: How it Began and Where it Stands Now in Nangarhar,” Afghanistan Analysts Network, July 27, 2016, www.afghanistan-analysts.org/the-islamic-state-in-khorasan-howit-began-and-where-it-stands-now-in-nangarhar/.

21. See “Summarized Administrative Review Board Detainee Statement,” projects.nytimes.com/guantanamo/detainees/108-abdul-rauf-aliza/documents/2.

22. “Heights and Weights Files,” Center for the Study of Human Rights, http://humanrights.ucdavis.edu/reports/heights-and-weights-files/ISN_058-ISN_121.pdf.

23. “Summarized Administrative Review Board Detainee Statement.”

24. Amir Mir, “Pakistan Now has a Native Daesh Ameer,” The News, January 13, 2015, www.thenews.com.pk/print/18141-pakistan-now-has-a-native-daish-ameer.

25. Amulets containing verses of the Koran believed to ward off evil spirits that Salafis, Wahhabis, and other fundamentalist sects view as shirk (idolatry or polytheism).

26. Dan Lamonthe, “Meet the Shadowy Figure Recruiting for the Islamic State in Afghanistan,” The Washington Post, January 13, 2015, www.washingtonpost.com/news/checkpoint/wp/2015/01/13/meet-the-shadowy-figurerecruiting-for-the-islamic-state-in-afghanistan/.

27. Rabi Al Akhir, Dabiq 7; and “Islamic State Appoints Leaders of Khorasan Province, Issues Veiled Threat to Afghan Taliban,” Long War Journal, January 26, 2016, www.longwarjournal.org/archives/2015/01/islamic_state_appoin.php.

28. “NDS Confirms Killing of Mullah Abdul Rawouf Khadim,” Khaama Press, February 9, 2015, www.khaama.com/mullah-abdul-rawouf-khadim-wounded-4-comrades-killed-in-drone-strike-29041.

29. The burning of a person’s house is a sanctioned form of punishment under Pashtun tribal law.

30. Mirwais Adeel, “ISIS Promotes Training Camp in Logar,” Khaama Press, April 29, 2015, http://www.khaama.com/isis-promotes-training-camp-in-logar-province-of-afghanistan-940.

31. The one possible exception was an April 18, 2015, suicide bombing that struck police and government workers queuing for salaries outside a bank in downtown Jalalabad, killing thirty-three. Though Islamic State Central never openly acknowledged the attack, and security analysts question whether the group had the operational capacity to carry out a suicide bombing in an urban center at this point, the spokesman for IS-K claimed responsibility, and Afghan president Ashraf Ghani also publicly pointed the finger at the Islamic State for the first time. In the months that followed, however, IS-K was either unwilling or unable to attack the government.

32. Sahil Mirwais, “130 Nangarhar Residents in Daesh Custody,” TOLOnews, August 12, 2015, www.tolonews.com/en/afghanistan/20868-130-nangarhar-residents-in-daesh-custody. A link to the video appears in Issue 11 of Dabiq, where ISIS takes credit for the execution.

33. For more on Taliban attitudes toward local populations and the correlation between opium poppy cultivation and support for the Taliban, see David Mansfield, “The Devil is in the Details: Nangarhar’s Continued Decline into Insurgency, Violence, and Widespread Drug Production,” Afghanistan Research and Evaluation Unit, February 2016, 7-8, http://areu.org.af/EditionDetails.aspx?EditionId=894&ContentId=7&ParentId=7.

34. In Achin district, IS-K has operated three separate “courts” with rudimentary accompanying jails. The courts in Achin report to a four-judge higher court located in Deh Bala district and presided over by Maulawi Naqibullah. The court in Deh Bala reportedly issues its judgment in written form and is also responsible for issuing fatwas, including one sanctioning the summary killing of all Taliban rank and file.

35. Two hundred suspected IS-K cadres were reported killed over a twenty-one-day period in February 2016. See Rahim Faiez, “Afghan President: ISIS is Being Wiped Out in Afghanistan,” The Associated Press, March 6, 2016, www.bigstory.ap.org/article/fd4a71e58abe4b7d8039235b561c3336/afghan-president-being-wiped-out-afghanistan.

36. These included an estimated eight hundred Pakistani nationals initially displaced from Pakistani military operations in FATA in 2014 moving from IS-K controlled areas of Nangarhar back to Pakistan between November 2015 and January 2016. Some, though not all, were families of former Tehrik-e-Taliban militants.

37. Rahim Faiez, “Afghan President: ISIS is Being Wiped Out in Afghanistan.”

38. “131 Daesh Fighters Killed in Nangarhar’s Ongoing Clash,” TOLOnews, June 26 2016, www.tolonews.com/en/afghanistan/25970-131-daesh-fighters-killed-in-nangarhars-ongoing-clash.

39. Mujib Mashal, “ISIS Claims Deadly Bombing at Demonstration in Kabul,” The New York Times, www.nytimes.com/2016/07/24/world/asia/kabul-afghanistan-explosions-hazaras-protest.html.

40. Jessica Donati and Habib Khan Totakhil, “Taliban, Islamic State Forge Informal Alliance in Eastern Afghanistan,” The Wall Street Journal, August 7, 2016, www.wsj.com/articles/taliban-islamic-state-forge-informal-alliance-in-eastern-afghanistan-1470611849.

41. “Islamic State Smuggling Timber Into Pakistan, Say Afghan Officials,” The Express Tribune, February 10, 2016, http://tribune.com.pk/story/1043687/islamic-state-smuggling-timber-into-pakistan-say-afghan-officials/.

About the Author

Casey Garret Johnson is an independent researcher focusing on violent extremism and local politics in Afghanistan.

For more information on issues and events that shape our world, please visit the CSS Blog Network or browse our Digital Library.