Public Opinions on Immigration

14 Aug 2012

Transnational migration today is increasingly being understood as a threat to national security. But is this sentiment widely shared by the populations of Europe and North America? Are European societies, for example, convinced that they will face additional problems from waves of migrants fleeing conflict and instability?

Not necessarily, argue the German Marshall Fund (GMF) and its partners. In their latest external pageTransatlantic Trendscall_made survey, they suggest that the social disruptions characterized as the Arab Spring have not significantly changed attitudes toward immigration. Moreover, their research suggests that Western public opinion towards immigration is more nuanced than might be expected. Accordingly, we begin today by presenting excerpts from the GMF’s main survey findings. In doing so, we offer our readers the chance to compare the results of the survey with the four factors that most prominently influence attitudes towards immigration, as identified by the Institute for the Study of Labor – economics, forms of identity, information flow and personal contact.

A major concern?

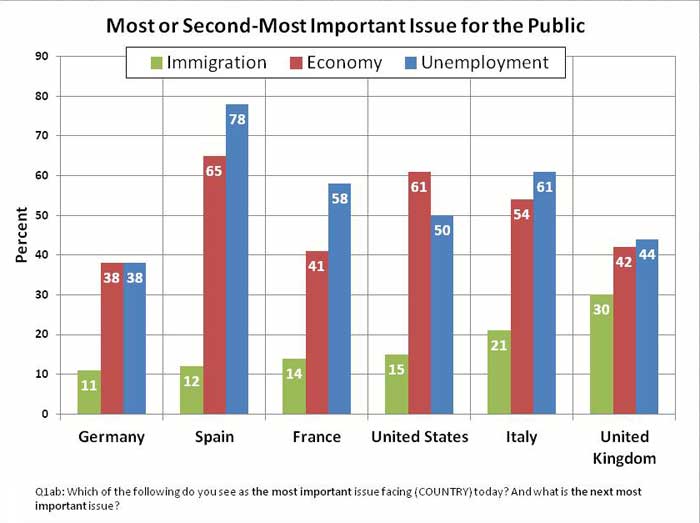

According to the GMF, in all of the Western countries surveyed – with the notable exception of Germany – just over half of the population viewed transnational migration as more of a societal-level problem than an opportunity. This was particularly true of the United Kingdom, where 68% of those surveyed perceived immigration as problematic. Yet while immigration is regarded as an important source of public anxiety, the GMF results suggest that it is often eclipsed by concerns over economic instability and rising unemployment, as the graph below demonstrates.

Too many immigrants?

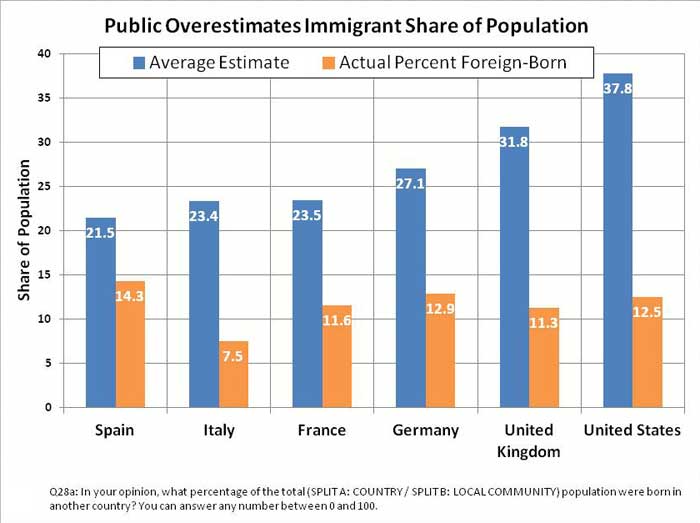

The majority of respondents from the United Kingdom also believed that there were too many migrants living among its indigenous population (57% in comparison to 50% in Italy, Spain and the United States, and only 33% of French and German respondents). However, the GMF’s findings also suggest that many Western societies overestimate the number of immigrants in their countries, and by extension this perceived problem. As the next chart shows this is particularly true of the United Kingdom, the United States and Italy.

Taking jobs and straining ways of life?

If there are divisions of opinion over just how severe problems of migration are, these divisions extend to another question – are immigrants taking jobs away from native workers, and are they additionally bringing down wage levels? The GMF survey shows that almost 60% of respondents in the United Kingdom and United States have such perceptions. Indeed, a similar number of respondents (63%) also regarded immigrants as a burden on both countries’ social services. Once again, however, these assumptions are not universally shared across Western countries. According to the GMF survey, only 34% of continental Europeans believed that immigrants took jobs away from the indigenous workforce, with 44% also perceiving immigration as bringing down wage levels.

For more subtle distinctions reflected by the GMF survey, listen below to Hamutal Bernstein, the German Marshall Fund’s Immigration and Integration Program Officer, or read the GMF’s full report on the external pageTransatlantic Trends websitecall_made.

Factors Influencing Hostility

Editor’s note: The following synopsis is based on “external pageHostility toward Immigration in Spaincall_made” by Ferran Martínez i Coma and Robert Duval-Hernández, published as IZA Discussion Paper No 4109,2009.

Economic explanations

When it comes to possible economic explanations for anti-migrant sentiment, Martínez i Coma and Duval-Hernández posit four hypotheses for our consideration.

They begin with the “resource hypothesis,” which claims that people who are experiencing financial stress will be more likely than those who are well-off to fear the implications of immigration. Hence, those persons in a difficult economic situation and/or who are insecure about their future should have more negative attitudes toward immigrants as potential economic competitors.

Second, we might consider the “job threat” hypothesis, which familiarly argues that anti-immigrant sentiments grow when native workers face higher competition in the labor market, particularly against immigrants with similar skill levels.

Third, there is the “pessimism hypothesis,” which highlights the role of individual perception about economic change. More precisely, the hypothesis states that “the belief that one is on a downward economic trajectory increases the tendency to view immigration as resulting in tangible costs to oneself and enhances restrictionist sentiment.”

Finally, individuals may have ‘res publica’ considerations when thinking about immigration. “This is known as the “ fiscal burden” hypothesis, and there are two intertwined facets to consider [here]. On the one hand, relatively poor natives will oppose immigration because resources are scarce and immigrants might compete with them for public services and benefits. On the other hand, wealthier natives might have a negative perception about immigrants because they might increase the cost of providing public services, causing their taxes to increase.”

Identity-based explanations

If the above economically-driven reasons for anti-immigrant sentiment aren’t enough, Martínez i Coma and Duval-Hernández warn us, we then have the problem of national identity to contend with. Indeed, immigration policy may lie at the heart of the definition of citizenship and national identity, but just what do we mean by the latter? Do we mean “in-group love” and “out-group hate”?

Well, according to our authors there are three factors to worry about when it comes to self-generated forms of identity – perceptual distinctiveness, salience and the perceived internal cohesiveness of a group. In the case of perceptual distinctiveness, immigrants may negatively stand out because they have a different skin color, dress differently, lack fluency in local languages, etc. In the case of salience, the cultural distinctiveness of migrant groups has received substantial media coverage since the mid-1990s, thereby inspiring periodic backlashes against the perceived exclusivity of such groups. Finally, if immigrants concentrate in certain areas, retain strong family and group loyalties, and continue to subscribe to common beliefs and distinctive cultural practices, then what is often perceived as a positive (group cohesion and solidarity) can be perceived as a threat to the cultural idiosyncrasies of a country.

Contact-centered explanations

Third, there is the question of how one interacts with migrant groups. The natural assumption, of course, is that as locals and new arrivals interact over time, cooperation will emerge in a “virtuous circle.” Unfortunately, such a positive relationship does not always arise in practice – i.e., “not all contacts are among equals, nor are they based on a democratic relationship. For example, given that the immigrants are mainly oriented toward low-skilled jobs, they will be in an unequal position compared to their employers.”

Second, one must also consider the nature of the contact. Private interactions, for example, typically involve proactive engagement on the part of natives. Interaction in the workplace, in contrast, can be merely passive and accidental, and thereby qualitatively different. The attitudes that any given individual has toward immigrants, therefore, might differ depending on the nature of the contact.

Information-centric explanations

Finally, Martínez i Coma and Duval-Hernández remind us that “tilting” against migrant groups may have economic, identity, and interaction-based causes, but it also may draw upon the actual information that natives have or don’t have about them. Matching up the perceived presence of a group with its actual statistical presence, for example, is an important way to condition opinions about immigration in a proportional and therefore positive way. (Gaps between perceptions and reality, in contrast, have more deleterious effects, to include heightened levels of hostility against new arrivals.)

To conclude then, what the GMF survey reminds us is that the securitization of transnational migration may be growing, but it may be on shakier ground, in terms of public support, than first meets the eye. Despite this good news story, at least in the minds of some, Martínez i Coma and Duval-Hernández then remind us that there are specific “tilts” we should be conscious of when dealing with migration issues. These tilts, if not managed properly, can represent the first steps in a securitization process that might not be as beneficial as some believe, as we will discuss tomorrow.