Dynamics of Radicalization and Violent Extremism in Kosovo

4 Jan 2017

By Adrian Shtuni for United States Institute of Peace (USIP)

This article was external page originally published by the external page United States Institute of Peace (USIP) on 19 December 2016.

Summary

- Kosovo, a country with no prior history of religious militancy, has become a prime source of foreign fighters in the Iraqi and Syrian conflict theater relative to population size.

- About three in four Kosovan adults known to have traveled to Syria and Iraq since 2012 were between seventeen and thirty years old at the time of their departure. By mid-2016, about 37 percent had returned.

- The vast majority of these known foreign fighters have moderate formal education. In comparative terms, this rate appears to be superior to the reported national rate. Two-thirds live in average or above-average economic circumstances.

- Five municipalities—four of which are near Kosovo’s Macedonian border—judging from their disproportionately high recruitment and mobilization rate, appear particularly vulnerable to violent extremism. More than one-third of the Kosovan male combatants originate from these municipalities, which account for only 14 percent of the country’s population.

- Long-term and targeted radicalization, recruitment, and mobilization efforts by foreign-funded extremist networks have been primarily active in southern Kosovo and northwestern Macedonia for more than fifteen years. These networks have often been headed by local alumnae of Middle Eastern religious institutions involved in spreading an ultra-conservative form of Islam infused with a political agenda.

- Despite substantial improvements in the country’s sociopolitical reality and living conditions since the 1998–1999 Kosovo War, chronic vulnerabilities have contributed to an environment conducive to radicalization.

- Frustrated expectations, the growing role of political Islam as a core part of identity in some social circles, and group dynamics appear to be the telling drivers of radicalization, recruitment, and mobilization in Kosovo.

Introduction

What started in 2011 as a popular uprising against the Syrian regime escalated in the five years that followed into an intractable sectarian war that has engulfed both Syria and Iraq, drawn in a suite of regional actors and world powers, and attracted an unprecedented number of volunteer combatants from more than a hundred countries. Although so-called foreign fighters have been a common feature of conflicts in Afghanistan, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Chechnya and Dagestan, Iraq, and most recently in Ukraine, their flow to Syria and Iraq is the largest influx of its kind in recent history. More than 36,500 individuals, including at least 6,600 from Western countries, are estimated to have traveled to the conflict theater since 2012, mostly to join designated terrorist organizations operating in the region.1

Not long after the bloody secessionist wars that brought about the disintegration of Yugoslavia in the 1990s, the Western Balkans became a prime source of foreign fighters for the Syrian conflict. More than a thousand nationals of Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Kosovo, Macedonia, Montenegro and Serbia are estimated to have traveled to the battlefields of Syria and Iraq since 2012.2 The significance of this number becomes apparent in the context of the combined population across these small countries of less than nineteen million. Rates of mobilization relative to the population size—particularly in Kosovo but also in Bosnia and Herzegovina and Macedonia—are far higher than in western European countries most afflicted by the phenomenon. Now that the flow of those traveling to the conflict theater has subsided—for a variety of reasons—and about 37 percent of all Kosovan nationals estimated to have traveled to Syria and Iraq have returned home, the task of understanding the dynamics of their radicalization has become even more critical. This is not only in regard to managing the security challenge associated with their return but also to adopting effective strategies for their rehabilitation and reintegration into society.

This report explores the dynamics of radicalization and violent extremism in Kosovo, focusing on the flow of foreign fighters as the most prominent symptom of a multifaceted religious militancy problem facing the country. It is important to emphasize from the outset that though the number of foreign fighters in itself represents a quasi-insignificant minority of the Kosovan society, it also constitutes merely a fraction of an extensive network of like-minded militants, supporters, and enablers who not only openly share the same ideology but are also actively engaged in its dissemination and recruitment efforts through physical and virtual social networks. This report shines some light on that less well-understood part of the supply chain of violent extremism.

Demographic Trends and Geographic Footprint

According to official data from May 2016, at least 314 Kosovan nationals are known to have traveled to Syria and Iraq since 2012.3 Of these, forty-four are women and twenty-eight are children. Forty others were intercepted by the police before they could reach the conflict theater.4 No official estimate exists for the number of children born to Kosovan parents in Syria and Iraq between 2012 and 2016, but social media research indicates that such children are not uncommon. About thirty-four individuals, or 11 percent of the Kosovan contingent, hold dual citizenship and are known to have resided in western European countries. Given these numbers, and a rate of more than 134 adult men—broadly categorized as foreign fighters—per million nationals, Kosovo is among the European countries most affected by this phenomenon relative to population size. Women and children are not counted as fighters given that they are generally considered noncombatants. That said, firsthand research indicates that a few teenage males have received weapons training and may have participated in armed hostilities, and that some women are actively involved in propaganda and recruitment efforts.5

To put Kosovo’s foreign fighter recruitment problem in perspective we compare it with Bosnia and Herzegovina, another Western Balkan country affected by the phenomenon. With 188 reported male combatants as of April 2016, Bosnia and Herzegovina has a foreign fighter recruitment rate of fifty-four per million nationals.6 Even if the recruitment rates were calculated based on respective Muslim populations—emphasizing that available estimates on religious affiliation are outdated and somewhat speculative—the foreign fighter rates would be higher in the case of Kosovo, 146 versus 105 per million.7

As of May 2016 about fifty-seven Kosovan men, some 18 percent of all nationals who have traveled to Syria and Iraq, are reported killed. No deaths among women and children have been reported. As many as 117 people (37 percent) have since returned to Kosovo. Returnees are overwhelmingly men; in other words, 45 percent of all men who traveled to Syria and Iraq have since returned. By contrast, only one in seven women, less than 14 percent, have returned to Kosovo. Given that most Kosovan women have reportedly traveled to Syria and Iraq with their husbands, this trend may indicate that the men who have traveled to the conflict theater with their spouses are arguably more committed to the cause and less likely to return home. At the same time, it is more difficult for women to leave the conflict zone because they can travel only when accompanied by a man. When their husbands are killed, widows are often forced to remarry. An estimated 140 Kosovan nationals, or 45 percent, were still in the conflict theater as of May 2016.

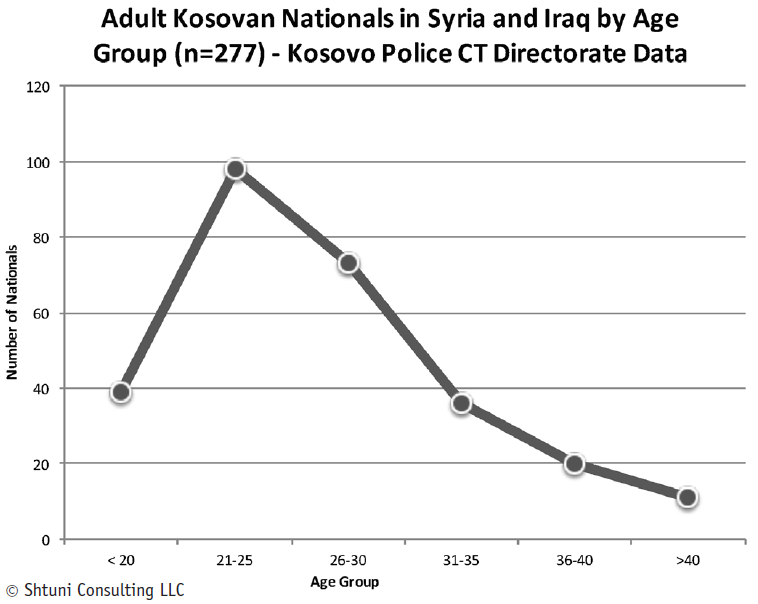

According to official demographic data provided by the Kosovo police, about 75 percent of Kosovan nationals of adult age (men and women) known to have traveled to Syria and Iraq after 2012 were born between 1984 and 1997. Considering that most Kosovans reached the conflict theater between 2013 and 2014, it is safe to conclude that they were largely between seventeen and thirty years old at the time of their departure or mobilization. The data suggest that the age group most vulnerable to mobilization is twenty-one to twenty-five years old, which accounts for more than a third of the total recruits, though the group represents only 9 percent of the country’s total population (see figure 1).8 This trend is consistent with the findings from a previous study on ethnic Albanian foreign fighters in Syria and Iraq.9

Figure 1. Adult Kosovan Nationals in Syria and Iraq (n=277)

Focusing more on male foreign fighters’ formal education, police records indicate that of the 142 Kosovans for whom educational data is available, 3 percent have completed elementary education, 87 percent secondary education, and 10 percent tertiary education. The overwhelming majority of known foreign fighters from this dataset have moderate rather than poor formal education, contrary to what anecdotal evidence sometimes indicates. Put differently, it is not necessarily or primarily the less educated—and by implication more uninformed—segments of society who are recruited to fight in Syria and Iraq.

In fact, the Kosovan foreign fighters’ rate of achieved tertiary education of 10 percent appears to be superior to the national rate, which according to the official 2011 census, is about 6.7 percent.10 Although Kosovo’s rate of achieved tertiary education is the lowest in the Balkans and in Europe, no causal relationship is observable between education and recruitment into transnational terrorism. Furthermore, the Kosovan contingent of foreign fighters appears to be better educated than their counterparts from Bosnia and Herzegovina, the majority of whom have only a primary-level education.11 By contrast, Bosnia and Herzegovina’s national rate of achieved tertiary education, at 12.7 percent, is almost twice as high as Kosovo’s.12

Nevertheless, the typical Kosovan foreign fighter is marginally less educated than the average foreign fighter at the time of joining the Islamic State, according to a study based on foreign fighter registration forms collected at the Syria-Turkey border between mid-2013 and mid-2014 by the Islamic State.13

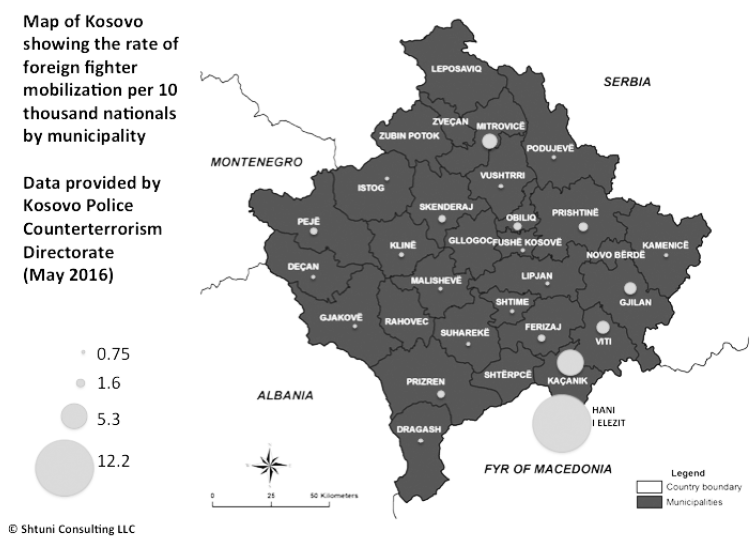

Mapping the footprint of the foreign fighter phenomenon in Kosovo is a critical step toward identifying the communities most vulnerable to radicalization, recruitment, and mobilization. The official demographic data on male foreign fighters confirmed that Kosovan recruits originate predominantly from the municipalities of Pristina (35) and Prizren (26). Yet, though these municipalities are home to about 25 percent of known recruits, they are also the country’s two most populous, home to about 20 percent of the national population. In sum, the phenomenon is observed most often in Pristina and Prizren but these municipalities are not necessarily where the problem is most acute.

Therefore, in determining with more accuracy the communities most vulnerable to foreign fighter mobilization for Syria and Iraq, and in turn assessing the etiology of the phenomenon at municipality and country level, it is arguably more useful to focus on the rate of mobilization per capita in each municipality rather than simple proportions (see figure 2). Calculations based on this methodology revealed that though virtually all of the twenty-seven municipalities with an ethnic Albanian majority have been affected by the phenomenon, five have a disproportionately high mobilization rate: more than two foreign fighters per ten thousand residents. Indeed, eighty-three recruits, or more than a third of the overall contingent of male foreign fighters, originate from these five municipalities, namely, Hani i Elezit, Kaçanik, Mitrovice, Gjilan, and Viti, which account for only 14 percent of the country’s population.

Moreover, the two tiny municipalities of Hani i Elezit and Kaçanik, which border the Republic of Macedonia, appear to be most vulnerable to foreign fighter mobilization, given that they have jointly contributed thirty fighters to the war in Syria and Iraq but account for only 2.4 percent of Kosovo’s population.

To put their numbers in perspective, Hani i Elezit and Kaçanik have respectively five and two times the rate of mobilization per ten thousand residents of the Belgian municipality of Sint-Jans-Molenbeek, often referred to as one of Europe’s most prolific jihadist hotbeds.14 In fact, the disproportionately high rate of mobilization is far from a coincidence. Extensive firsthand research and numerous counterterrorism operations in both Kosovo and Macedonia appear to indicate that the rate is the result of targeted and effective radicalization, recruitment, and mobilization efforts by extremist networks that have operated in that particular geographic space across borders for over a decade. This is further substantiated by the fact that Skopje, the nearby capital city of Macedonia, which has close ties to southern Kosovo is in the world’s top five locations for volume and proportion of Islamic State foreign fighters per capita, according to a recent study based on Islamic State registration forms leaked in early 2016.15

Figure 2. Rate of Foreign Fighter Mobilization by Municipality

Socioeconomic and Political Factors

Kosovans were undoubtedly the most socially marginalized and discriminated people in Yugoslavia. Their basic political rights and social liberties were systematically denied under Slobodan Miloševic’s repressive regime. They were also the worst off educationally and economically, and had staggeringly high rates of unemployment driven by ethnocentric state policies. Yet, this host of adverse conditions, often cited as push factors that drive recruitment into violent extremist groups, did not push Kosovans toward violent extremism any more strongly than other people in Yugoslavia.16 On the contrary, the Kosovan leadership, headed by President Ibrahim Rugova, explicitly chose nonviolent resistance for many years to address oppression under Miloševic’s regime. In fact, in the early 1990s, violent ethnosectarian conflicts broke out much earlier in other parts of Yugoslavia—Slovenia, Croatia, and Bosnia and Herzegovina—among Orthodox Christians, Roman Catholics, and Muslims alike. Only at the end of the 1990s did Kosovans resort to violence for political ends, opting to wage guerrilla warfare against government forces. A brief insurgency followed in Macedonia along the border with Kosovo.

In relative terms, though still lagging behind all former Yugoslav republics in economic performance and social development, Kosovo since the 1998–1999 war has progressed steadily according to most measurable socioeconomic indicators and observable social and political conditions. The state of political rights and social liberties has improved. Kosovans now have an independent state and elected representatives, and receive education in their own language in an increasingly high number of educational institutions. On a per capita basis, Kosovo has also received the largest flow of aid distributed by the international community to a developing country.17 This, paired with the flow of remittances from the sizable diaspora in western Europe, has had a substantial positive impact on the country’s economy. In 1989, Kosovo’s GDP per capita was 25 percent that of Serbia and 40 percent that of Bosnia and Herzegovina.18 By 2015, it had risen to 67 percent that of Serbia and 80 percent that of Bosnia and Herzegovina.19 Despite being lower-middle-income, Kosovo is one of only four European countries to experience uninterrupted growth since the onset of the global financial crisis in 2008.20

According to World Bank data, registered unemployment in Kosovo in 2014 stood at 35 percent. Youth unemployment was even higher.21 Indeed, unemployment is one of the country’s most serious challenges. Yet the official unemployment rate among Kosovo’s ethnic Albanian majority has halved relative to 1997, just before the start of the conflict.22 Moreover, although Kosovo has one of Europe’s highest unemployment rates, at least part of that problem is attributable to informal employment, which the International Monetary Fund reports as being widespread in the country. In fact, according to the 2011 census only fifteen thousand people were formally working in agriculture, but studies from the Kosovo Agency of Statistics indicate that the actual number was ten times as high.23

Indeed, it would be hard to deny that in relative terms the trajectory of the country overall has been positive. Kosovans have legitimate reason to be somewhat content and optimistic. According to a 2008 Gallup poll, the year Kosovo proclaimed its independence from Serbia, Kosovans were the most optimistic people in the world.24 Attitudes, though, would appear to have soured since 2008. According to a recent poll, in 2015 Kosovo was the third unhappiest country in Europe.25 The most emblematic display of the popular dissatisfaction with the country’s reality came when about a hundred thousand Kosovans—5.5 percent of the population—applied for asylum in European Union (EU) states between mid- 2014 and mid-2015.26

Meantime, Transparency International ranked the country much lower than any of the other Western Balkan countries in the 2015 Corruption Perception Index.27 These perceptions are in line with the findings of the National Democratic Institute’s Kosovo May 2016 Focus Group Report, according to which focus group participants “expressed little trust in most government institutions, and perceived them as largely corrupt, self-interested and incapable of addressing important issues for ordinary citizens.”28 The distrust in government institutions and politicians is also reflected in the findings of the 2015 Kosovo Security Barometer, according to which the government and the Assembly of Kosovo are the two least trusted public entities.29 By contrast, religious institutions enjoy extraordinarily high levels of popular confidence that are twice as high.30 Kosovo’s sociopolitical reality and living conditions have improved, but the country still faces pervasive perceptions of failed leadership efforts, corruption, and unmet popular expectations. Indeed, as previous studies demonstrate, rising and frustrated expectations are a far more common source of extremism than economic deprivation.31

This frustration, however, is unlikely to sufficiently explain either Kosovo’s high radicalization, recruitment, and mobilization rates or its considerable reactionary gravitation toward religious leadership and dogmatic values. Rather than a simple byproduct of socioeconomic and political dynamics, these outcomes are as much the fruit of sustained and targeted investments by various Islamic countries that use religion as a foreign policy tool—often aggressively promoting the primacy of religious identity and a conservative Islamic way of life in open tension with Kosovo’s religious tradition and Western liberal democracy—as they are the result of a peoples’ quest for a more constant identity that transcends competing, and at times confusing, national, state, and supranational identities.32

Specific Socioeconomic Considerations

According to related police records (mostly self-declared after arrest) of 112 known foreign fighters, about 64 percent are in average or above-average economic circumstances, and only about 36 percent in poor circumstances. Furthermore, none of the five municipalities with the highest rates of foreign fighter mobilization (Hani i Elezit, Kaçanik, Mitrovice, Gjilan, and Viti) are among the municipalities with the lowest 2014 Human Development Index in Kosovo.33 In other words, taking into account the limit to what can be inferred based on available data, no correlation is readily observable between income and educational levels and vulnerability to mobilization. Indeed, extreme poverty and low levels of education in Kosovo are highest in other municipalities—such as Skenderaj, Kastriot, and Malisheve—and disproportionately high among ethnic minority households, especially in Roma, Ashkali, and Egyptian communities (predominantly Sunni) in the central and western parts of the country.34 Yet nothing suggests that large numbers from these communities have left for Syria and Iraq.35

Geopolitics and Identities in Flux

The Western Balkans, lying as they do between Europe and Asia, have historically been a region where competing dogmas, ideologies, and spheres of influence have intersected and often collided. Not accidentally, national and religious identities are so entrenched and intertwined in this region traditionally shaped by external powers rather than internal dynamics. Islam is one of the main legacies of the long Ottoman conquest and rule in the Balkans, where over a few centuries large swaths of indigenous populations converted from Christianity to Islam. With more than 90 percent of its population considered either observant or nominal Muslim, Kosovo has the highest proportion of Muslims relative to population size in the Western Balkans. Nevertheless, unlike in Bosnia and Herzegovina, where Islam has been long regarded as an ethnic marker, in Kosovo it has traditionally been much less significant than the Albanian ethnic identity. Communism also diminished the role of religion in society for almost half a century.

In the aftermath of the Cold War, a suite of powerful states with aggressive foreign policy agendas rushed to restore historical ties to the region or to spend petrodollars to acquire new influence. Investments were made in strategic economic sectors and in reviving cultural and religious heritage in the region. Much effort also focused on spreading an ultra-conservative form of Islam infused with a political agenda through Middle Eastern charities at times infiltrated by violent extremist organizations.36 The efforts of faith-based organizations, primarily from the Persian Gulf states but also Turkey, intensified extensively after the 1998–1999 Kosovo War. Indeed, numerous Middle Eastern charities often accused of actively spreading Wahhabism set up chapters in Kosovo and dedicated considerable resources to building an extensive network of unlicensed mosques across the country, providing educational scholarships to hundreds of talented Kosovan youths to study in religious institutions in the Middle East, and sponsoring Koranic schools and local faith-based organizations often led by local fundamentalist alums of Middle Eastern religious institutions.37

Aside from providing much needed humanitarian aid and social services these faith-based organizations promoted a pan-Muslim identity rooted in principles of brotherly solidarity, which was particularly appealing to Kosovans at that critical juncture in their postwar healing and recovery. To be sure, many foreign aid and faith-based entities from both the East and the West provided assistance to Kosovans after the war, but none had a stronger agenda that directly addressed identity needs and provided spiritual and emotional support at the grassroots level than Islamic organizations. Some of these painstakingly invested in an expansive religious infrastructure that provided people with spiritual comfort and a sense of community, and identity seekers with structure, guidance, perspective, belonging, and a sense of mission. These organizations planted the seeds of a new group identity shaped in the mold of political Islam that gradually came to fruition with the galvanizing effect of the armed conflict in Syria and Iraq. This emotional solidarity and religious guidance in the postwar context was arguably as meaningful to long-victimized and long-segregated Kosovans as humanitarian aid itself, if not more so.

With time, local radical imams were able to use this newly crafted religious bond with the Ummah (supranational Islamic community) to recast the Kosovans’ grievances and struggles as local manifestations of a greater global trend of oppression against Muslims. In a video statement from 2010 posted online, a Kosovo Liberation Army veteran and the first Kosovan to be reported killed in Syria in November 2012 provided his view on the reasons behind the Kosovo War. “Those who fought us were crusaders. Those who think that the Kosovo War was a nationalist war are wrong! [The Serbs] came here to fight against Islam.”38 In this video he appears alongside a much younger leading activist of a faith-based nongovernmental organization operating in Kaçanik who will go on to become a Kosovan Islamic State commander. In another propaganda video posted on YouTube in late 2013 this commander, among threats and calls to action, expresses his appreciation for the opportunity Allah gave him to “defend the honor of Muslim sisters and Muslim children in Syria.” Judging from a large number of similar statements posted continuously on social media platforms and even made by returned foreign fighters in trial, the excessively high rate of radicalization and mobilization among particular circles of young religious Kosovans may be more plausibly explained by their professed feelings of solidarity with the Islamic community they integrated in—the Ummah—than through other socioeconomic drivers. The systematic efforts of a cohort of fundamentalist clerics from Kosovo and Macedonia currently convicted or under criminal investigation, and the active network of faith-based organizations affiliated with them, now largely closed down, have been particularly instrumental in this process. Indeed, this sensation of intra-community solidarity has been reinforced by some clerics interpretation of the armed conflict in Syria and Iraq as defensive jihad, a compulsory duty for all Muslims who should act in solidarity with other Muslims under attack. The recent memories of violence, rape, humiliation, and massive expulsion from their homes during the Kosovo War arguably made the work of recruiters on Kosovans less challenging because the plight of the Sunnis in Syria closely resonated with them.

Unsuccessful Integrations and Religious Revival

For generations, Kosovans have lived in a sociopolitical reality where they were made to feel unequal and unwanted. They struggled or refused to properly integrate in former Yugoslavia in part because of outright discrimination but also in fear of assimilation by the Slavic majority in a country where they were both an ethnic and a religious minority. This caused them to integrate Islam into their lives not simply as a dogma but also as part of a pragmatic strategy of ethnic and territorial preservation.39 In a country where they could face prison for using the Albanian national flag they could at least build mosques to demarcate their territory and proclaim their diversity. In other words, religion became somewhat of a metaphor for ethnic identity.

The constantly frustrated nationalist aspirations of joining Albania, regarded as the mother state, also did not help with integration. Yugoslavia’s collapse both as a political system and a social project—that is, as a multinational federation and a socialist society—brought more fragmentation. The Kosovo War and its aftermath further deepened ethnocultural cleavages, resulting in an even more polarized society. Despite Yugoslavia’s defeat in 1999, the aspirations of those in Kosovo who sought unification with Albania or outright independence were once more constrained. Kosovo instead became a protectorate managed by the international community until February 2008. Even the transition to an independent state has been rocky and fraught with recurring disappointments. This reality of constant shifts, transitions, failures, and thwarted integration aspirations has arguably pushed Kosovans closer to their religious identity—the one that has remained constant—in a sort of religious awakening. According to a 2012 study, although 58 percent of the respondents said they are “just a Muslim,” only 41 percent reported growing up with this identity, and a substantial percentage of Kosovan Muslims said they were unaware of their childhood affiliation.40 Nevertheless, this religious awakening should not be confused with religious militancy. Only a small fraction of those who gravitate toward religion end up tangled in the web of violent extremist organizations. Yet the scale of this revival would have been unlikely without the vigorous efforts of faith-based organizations.

Indeed, though for Kosovans the aspired supranational European identity has become increasingly elusive given the plethora of obstacles to EU integration, the national Albanian identity unfeasible and frustrating in light of clear indications by the international community that it will not accept border changes or unification with Albania, and the prescribed Kosovar state identity somewhat confusing for its fluidity, the Muslim identity appears to have become increasingly appealing and is gaining significant ground. According to a 2016 survey by a think tank focusing on the issue of identity among ethnic Albanians in Kosovo, almost one-third of respondents identified either primarily or exclusively as Muslims rather than Albanian.41 The conservative part of this new reality is on display in the streets of Kosovo, where it is increasingly common to come across women wearing the hijab and men sporting the Salafi’s trademark long beard with the upper lip clean-shaven and above-the-ankle slacks. This trend was much less observable immediately after the war.

That Kosovo is the only country in the Western Balkans that does not enjoy visa-free travel within Europe is adding to the frustration and contributing to a general feeling of isolation and alienation from the rest of Europe, especially among the country’s youth. The widely shared perception of being unwelcomed or unwanted in Europe is associated with resentment toward a political class that has repeatedly failed to meet the benchmarks set by the European Union as conditions for visa-free travel.

Martial Social Identity and a Legacy of War

According to various studies, adoption of a religious belief system provides a fulfilling and cohesive social identity and sense of belonging to a broader cultural community.42 Aggression and acts of violence against the members of “their community” (despite geographic distance) perpetrated by another group provoke in some individuals a transformative process described as “a self-categorization into a martial social identity.”43 Believing they are soldiers protecting their community and doing the will of God, they adopt violence as a justified method of defense. This is believed to be one of the most common pathways to political violence.

Similarly, a handful of Kosovan foreign fighter interviews and statements before, during, and after their participation in the war in Syria and Iraq capture perspectives in line with this idea, the concept of humanitarian jihad interwoven in their narrative. In a televised interview in early 2016, a highly educated returnee—who elected not to hide his identity— explained: “I decided to travel to Syria for humanitarian reasons.…I did not leave because I was desperate…and can’t deny the role of religion. Sacrificing oneself to protect someone who is defenseless is a noble cause.” One of the first known returnees gave a similar interview in 2013, claiming that his motivations were shaped by the urge to defend civilians and fulfill a religious duty: “I left for Syria for religious reasons; I saw that the Shia and Alawites started waging war against Sunnis.…Inspired by the Koran and the teachings of the Prophet I decided to travel to defend the country…every Muslim is obliged to wage war against nonbelievers.” Along the same lines, a high school teacher turned jihadist who was arrested in 2014 told a journalist, “I got the idea from viewing videos online. I was deeply disturbed. I knew I would go one day. The Koran and Muhammad’s teachings clearly stipulate that a day spent waging jihad is equal to sixty years of piety and devotion.”

The legacy of the Kosovo War is referenced prominently in returnees’ accounts. A seemingly disillusioned young man who traveled to Syria in 2013 told a journalist under conditions of anonymity, “When the Arab Spring began, I wanted to help the Syrian people. I have experienced war and horrific raids firsthand as a child in Kosovo, and wanted to help those children, the families.” In another interview to an Italian TV station, a Kosovan youth under house arrest showed a mix of remorse and resolve fueled by his childhood war experience: “It was a mistake. I should not have left for Syria. I saw the images of Syrian population being massacred. We know well what war is in Kosovo and that the international community should help people seeking liberty from the yoke of tyranny.” A waiter who had just returned to Kosovo from a short stint in Syria in 2014, instead spoke of his experience as a rite of passage, emphasizing an anticipated feeling of fulfillment brought about by going to war: “I spent time watching videos of Assad’s cruelties against Syrian children. I wanted to fight against that criminal man. I also wanted to experience war. During the Kosovo War I was too young to fight, which made me feel like I was incomplete.”

As often the case with clan-based societies, Kosovo is dominated by an entrenched patriarchal mindset where rigid gender norms place harsh expectations on young men. Physical toughness, bravery, and eagerness to fight are often regarded as traditional traits of successful and honorable men.44 In the aftermath of the Kosovo War, the constant overflow of narratives and epic songs that glorify the manliness and heroism of Kosovo Liberation Army fighters has further reinforced these social values.

Although returnees appear more inclined to cite humanitarian reasons and moral outrage as motivations for traveling to Syria, the fighters issuing video statements from the conflict theater put much more emphasis on the opportunity to wage jihad. A student of Islamic studies killed in July 2014 explained his decision in an Islamic State propaganda video posted online: “I came [to Syria] for Jihad, so that the word of Allah is the highest and sharia is our law.” In another video statement, a former firefighter turned foreign fighter and eventually killed in Syria in 2015 exclaimed, “May our generation be the one to destroy all the hypocrites, nonbelievers and rejectionists.…We will not stop until we elevate the word of Allah across the world and make sharia the only law.” Likewise, in a bellicose video statement issued in January 2014 the most prominent Kosovan foreign fighter and a successful recruiter said, “We will strive to establish the Islamic State in Iraq, Syria and all around the world. We will either achieve our goal or you, nonbelievers, will walk on our dead bodies. I call on you Muslims, when will you wake up?”

Inspirational Leadership and Group Dynamics

The 314 Kosovan nationals who have traveled to Syria and Iraq are the most visible part of the problem but this contingent neither appeared nor operates in vacuum. Firsthand research on the dynamics of radicalization and recruitment in the Western Balkans online suggests that those who openly support the cause and disseminate the ideology of terrorist organizations such as the Islamic State, al-Qaeda, and Jabhat Fateh al-Sham (previously Jabhat al-Nusra) are in the thousands. The Facebook page “Halal Channel” run from Pristina by Islamic State supporters had more than eight thousand followers at the time it was shut down in July 2016. The Jabhat Fateh al-Sham page “Minarja e Bardhe” or “The White Minaret” (also run from Pristina) had almost four thousand followers before being shut down in June 2016 only to reopen again shortly thereafter. These social media pages are only two of many platforms where Albanian-speaking individuals from diverse social and economic backgrounds congregate to create virtual communities that transcend geographic limitations. In this regard, far from an individual process, radicalization and recruitment are more than anything else collective or social activities.

The response of the Kosovan authorities so far has mainly focused on criminalizing participation in foreign conflicts and cracking down on recruiting cells and returnees. From 2013 to July 2016, the Kosovo police have kept 292 individuals suspected of involvement in acts of terrorism or promoting religious extremism under surveillance. Criminal charges have been brought against 219, 119 have been arrested, and indictments have been filed against 92.45 The last five indictments were lodged in mid-September 2016 against four of the most prominent conservative clerics and the leader of an Islamist political party in Kosovo. In fact, the number of Kosovan clerics known to have traveled to Syria and Iraq to join jihadist groups or to have been arrested by authorities on charges related to terrorist activities stands at seventeen. The corresponding numbers for Albania and Macedonia are four and three, respectively.

Kosovo has cracked down more aggressively than neighboring countries on fundamentalist clerics and their associates, but the disproportionately larger number of these clerics arrested as part of numerous counterterrorism operations points to the significance of religious leadership in the radicalization, recruitment, and mobilization dynamics within Kosovo. Indeed, these inspirational figures make up one of the main observed clusters of Kosovans actively involved in violent extremist activities in Kosovo, both on the ground— through a number of so-called cultural associations—and on social media. The other one is composed of foreign fighters connected to each other through kinship ties. Firsthand research on male Kosovan foreign fighters (excluding noncombatants) indicates at least eleven cases of two or three brothers and other cousins traveling together to Syria and Iraq, for a total of twenty-eight known fighters. In one case, ten members of the same family— three brothers with their two wives and five children—left for Syria in late 2014.46 Preliminary research also suggests that in a large number of cases known fighters were neighbors or friends who followed the same clerics or belonged to the same faith-based grassroots organizations. Although more in-depth research is needed for Kosovo, the described trends appear to be in line with the findings of anthropologist Scott Atran, that group dynamics are critical in turning ordinary people into violent extremists.47

Conclusion

The foreign fighters currently in the battlefields of Syria and Iraq are only one manifestation of violent extremism in Kosovo. Another significant part of the supply chain of violent extremism includes fundamentalist clerics and key influencers involved in proselytizing and radicalization efforts, recruiters, facilitators, would-be fighters intercepted by the police before they could get to Syria and Iraq, and the plethora of like-minded activists supporting and promoting violent extremism online and on the ground. Yet another contingent is composed of Kosovan women, children, infants born in the conflict theater, and other family members of fighters who either decided or were forced to migrate with the combatants. Another includes returnees either serving prison sentences or struggling to be reintegrated in the society, though it is hard to determine with certainty their intentions. Then, inevitably, are the invisibles, those who have managed to stay under the radar, about whom the authorities know nothing. This mosaic of people with various levels of ideological conviction (in some cases arguably none at all) and involvement in the armed conflict in Syria and Iraq is still incomplete. Their families, relatives, and friends are directly affected by the phenomenon and remain particularly vulnerable to violent extremism.

The age group most susceptible to mobilization into violent extremism is twenty-one to twenty-five year olds. The typical Kosovan fighter has a moderate formal education and lives in average or above-average economic circumstances. A range of reasons explain why Kosovans become directly or indirectly, willingly or forcibly involved in violent extremism, but economic deprivation and inadequate education are not among them. Instead, factors closely tied to a recent past defined by interethnic strife, segregation, and victimization and a current reality marked by popular perceptions of failed leadership efforts and unmet expectations against a backdrop of identities in flux in a nascent country struggling to define itself appear to be more relevant. Yet foreign fighter mobilization is not spread uniformly across the country. It is instead particularly concentrated in a cluster of contiguous municipalities (Hani i Elezit, Kaçanik, Gjilan and Viti) near the border with Macedonia. Although more detailed research is needed for a comprehensive assessment, this trend can be attributed in large part to the radicalization, recruitment, and mobilization efforts by extremist networks that have operated in that particular geographic space across borders for more than a decade. Relatedly, social networks and group dynamics appear to be of particular significance, and would request special attention especially as they relate to Middle Eastern trained radical clerics who have successfully taken on leadership roles, channeled the frustrations of the youth, and fostered the creation of a martial social identity.

Assessing the extent and complexity of this mosaic and the dynamics that have given shape to it is the first step to understanding the range of social vulnerability and security threats that Kosovo and the region are and will be subject to for some time to come. Such assessment will require not only adequate technical expertise, resources, and coordination but also political will, resolve, and focus to expose the nature, scale, and scope of the problem and to adopt policies to tackle it at its root in a comprehensive but nuanced way, not overwhelmingly through law enforcement and punitive measures but primarily through civil activism and community-based programs that raise awareness and strengthen the community’s immunity to violent extremism.

Recommendations

Numerous factors—including criminalizing participation in armed conflicts abroad—have contributed to a significant drop in the outflow of Kosovan foreign fighters. This positive trend is not to be overlooked. Yet the relatively robust level of support for violent extremist organizations, particularly visible online, advises against assuming that repressive measures by themselves have countered the problem. The Kosovan government and international policymakers and practitioners would do well to take the following steps.

- Resist the temptation of overestimating the impact of the reactive measures implemented so far and downplaying the actual level of sympathy or support that some violent extremist organizations and the core beliefs they espouse continue to enjoy among particular segments of the population. To be sure, this approach will not come without political and image costs in the domestic and international arena. Moreover, considering the lingering interethnic tensions in the region and Kosovo’s EU integration ambitions, exposing the full extent of the country’s “vulnerability to violent extremism” may even seem injudicious. Yet, the long-term cost of misdiagnosing and undertreating this critical social ill far outweighs any short-term public relations and political benefits.

- Close down informal places of worship and faith-based nongovernmental organizations that promote interethnic and racial hatred or have proven links to violent extremist organizations. Doing so is critical. Yet it is arguably even more critical not to leave a vacuum behind. Rather, focus more efforts on promoting, fostering, and facilitating other genuine grassroots initiatives and platforms for citizen participation and community support.

- Intensify efforts to implement the National CVE Strategy with the support of international partners. In particular, support community-based early-intervention and prevention programs and target the age groups and geographic communities most vulnerable to radicalization. Identify the factors that, judging from their low rate of recruitment into violent extremist activities, make some municipalities significantly more resilient to radicalization.

- Prioritize programs for the rehabilitation and reintegration of returnees—both within prisons and outside them—as well as their families. Inform such programs with both academic research and best practices from similar projects in other countries, being mindful of local resource and capacity constraints. Harness the capacities of civil society and community groups that are uniquely placed to provide continued reintegration support. Build these programs on a sound understanding of local dynamics of radicalization and violent extremism and a thorough and ethical assessment of Kosovan returnees’ reasons for returning, their grievances, and their needs.

- Coordinate closely with international donors and local implementers of preventing violent extremism, CVE, and reintegration programs to avoid duplication of efforts, increase effectiveness of interventions, and maximize limited resources. Resist the temptation of centralizing the implementation process. Build close partnerships with municipality-level stakeholders and work with local implementers wherever the expertise allows.

- Partner with organizations and specialists with established CVE capacity building and programming expertise to develop local capacity to raise awareness and counter violent extremism online. Dedicate particular attention to providing young activists with the skills and means to run public information campaigns systematically, safely, and effectively with the end goal of creating independent regional networks of CVE activists.

- Prioritize preventive and rehabilitation efforts on the five identified municipalities that have shown a heightened vulnerability to violent extremism. This is particularly important in view of limited resources and capabilities. The successful outcome of these targeted efforts will hinge as much on the quality of interventions, constancy of engagement, and adaptability to dynamic radicalization trends as on the ability of stakeholders to address the problem set with empathy, avoiding overly securitizing communities or stigmatizing specific populations.

Notes

1. U.S. Congress, Senate Select Committee on Intelligence, “Worldwide Threat Assessment of the US Intelligence Community” (statement of James R. Clapper, Director of National Intelligence, February 9, 2016).

2. Adrian Shtuni, “Islamic State Influence Threatens the Western Balkans” (London: IHS Jane’s Defense and Security, 2016).

3. Kosovo police official data provided to the author, May 2016.

4. Erjone Popova, “About 140 Kosovan Nationals in the War in Syria and Iraq,” Kallxo, July 19, 2016, http://kallxo .com/afer-140-kosovare-ne-lufterat-ne-siri-e-irak/.

5. Shtuni, “Islamic State Influence Threatens the Western Balkans.”

6. Vlado Azinovic and Muhamed Jusic, “The New Lure of the Syrian War: The Foreign Fighters Bosnian Contingent,” Atlantic Initiative, 2016.

7. Kosovo Agency of Statistics, “Kosovo Census 2011” (Pristina, 2012); Agency for Statistics of Bosnia and Herzegovina, Census of Population, Households and Dwellings in Bosnia and Herzegovina, 2013: Final Results (Sarajevo, June 2016). Because considerable proportions of foreign fighters originating from western European countries are recent converts to Islam—possibly as many as a quarter in the case of France—calculating and comparing the rate of foreign fighter mobilization for Syria and Iraq based exclusively on demographic data on respective Muslim populations in European countries and countries of the Western Balkans would yield a skewed perspective of recruitment and mobilization trends. However, the comparison of the rates of foreign fighter mobilization among the countries of the Western Balkans based exclusively on Muslim populations may be less problematic given the marginal number of recent converts among the nationals known to have traveled to Syria and Iraq.

8. Kosovo Agency of Statistics, “Kosovo Census 2011.”

9. Adrian Shtuni, “Ethnic Albanian Foreign Fighters in Iraq and Syria” (New York: CTC Sentinel, 2015): 11–14.

10. Kosovo Agency of Statistics, “Kosovo Census 2011.”

11. Azinovic and Jusic, “The Lure of the Syrian War.”

12. Agency for Statistics of Bosnia and Herzegovina, Census of Population, Households and Dwellings in Bosnia and Herzegovina, 2013.

13. Nate Rosenblatt, “All Jihad Is Local: What ISIS’ Files Tell Us About Its Fighters,” New America, July 20, 2016.

14. Bibi van Ginkel and Eva Entenmann, eds., The Foreign Fighters Phenomenon in the European Union: Profiles, Threats & Policies, ICCT Research Paper (The Hague: International Centre for Counter-Terrorism 2016); T. Hume, “Brussels raids: Police hit Molenbeek, area at heart of Belgium’s jihadist threat,” CNN.com, 2015; Emma-Kate Symons, “Belgium attacks–10 years ago, this undercover reporter warned of terror hotbeds in Brussels,” New York Times, March 25, 2016.

15. Rosenblatt, “All Jihad Is Local.”

16. Guilain Denoeux and Lynn Carter, Guide to the Drivers of Violent Extremism (Washington, DC: USAID, February 2009), http://pdf.usaid.gov/pdf_docs/pnadt978.pdf.

17. Aiden Hehir, “How the West Built a Failed State in Kosovo,” The National Interest, August 31, 2016.

18. Mills Kelly, “GDP in Yugoslavia: 1980–1989,” Making the History of 1989, Item #671 (2016) https://chnm.gmu .edu/1989/items/show/671.

19. Trading Economics, “Bosnia and Herzegovina GDP per capita, 1994–2016,”December 2016, www.tradingeconomics .com/bosnia-and-herzegovina/gdp-per-capita.

20. World Bank, “Kosovo: Country at a Glance,” www.worldbank.org/en/country/kosovo.

21. Kosovo Agency of Statistics, “Results of the Kosovo 2014 Labour Force Survey” (World Bank, June 2015, http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/629671468190183189/Results-of-the-Kosovo-2014-labour-force -survey.

22. William Zartman and Tanya Alfredson, “Negotiating with Terrorists and the Tactical Question,” in Coping with Terrorism: Origins, Escalation, Counter Strategies, and Responses, ed. Rafael Reuveny and William Thompson (Albany: State University of New York, 2010).

23. World Bank, “The World Bank Group in Kosovo–Country Snapshot,” April 2015, www.worldbank.org/content /dam/Worldbank/document/eca/Kosovo-Snapshot.pdf.

24. Gallup International and INDEX Kosova, “Kosovo–The Most Optimistic Again,” December 18, 2008, www .indexkosova.com/docs/doc2_8.pdf.

25. Happiness Research Institute, “Happiness Equality Index: Europe 2015,” 2016, www.happinessresearchinstitute .com/publications/4579836749.

26. Susanne Koelbl, Katrin Kuntz, and Walter Mayr, “What Is Driving the Balkan Exodus?” Spiegel Online, August 26, 2016, www.spiegel.de/international/europe/western-balkan-exodus-puts-pressure-on-germany-and -eu-a-1049274.html.

27. Transparency International, “Corruption Perceptions Index 2015,” www.transparency.org/cpi2015/.

28. National Democratic Institute, “Kosovo 2016 Focus Group Report” (copy in author’s possession).

29. Kosovar Center for Security Studies, Kosovo Security Barometer, Fifth edition,” December 2015, www.qkss.org /repository/docs/Kosovo_Security_Barometer_-_Fifth_Edition_523670.pdf.

30. Ibid.

31. Denoeux and Carter, Guide to the Drivers of Violent Extremism.

32. Adrian Shtuni, “Breaking Down the Ethnic Albanian Foreign Fighters Phenomenon,” Soundings 98, no. 4 (2015): 460–77.

33. Matthias Lücke et al., Kosovo Human Development Report, 2014: Migration and a Force for Development (Kosovo: United Nations Development Programme, 2014), http://hdr.undp.org/sites/default/files/khdr2014english.pdf. The Human Development Index is a summary measure of key dimensions of human development. It measures the average achievements in a country in three basic dimensions of human development: a long and healthy life, access to knowledge, and a decent standard of living.

34. Kosovo Foundation for Open Society, “The position of Roma, Ashkali and Egyptian communities in Kosovo,” 2009.

35. World Bank, “Kosovo Country Snapshot.”

36. Adrian Shtuni, “Ethnic Albanian Foreign Fighters in Iraq and Syria.”

37. Ibid.; David Gardner, “Saudis have lost the right to take Sunni leadership,” Financial Times, August, 13, 2014; Besiana Xharra, “Kosovo turns blind eye to illegal mosques,” Balkan Insight, January 12, 2012.

38. Gazeta Express, “Lavdrim Muhaxheri in Pristina: Serbia Fought Our Islam,” video, September 29, 2015, www .gazetaexpress.com/lajme/lavdrim-muhaxheri-ne-mes-te-prishtines-serbia-erdhi-te-na-e-luftoje-islamin-video -133589/?archive=1.

39. Shtuni, “Breaking Down the Ethnic Albanian Foreign Fighters Phenomenon.”

40. Pew Research Center, “The World’s Muslims: Unity and Diversity,” August 9, 2012, www.pewforum.org/2012/08/09 /the-worlds-muslims-unity-and-diversity-executive-summary/.

41. Agon Demjaha and Lulzeim Peci, “What Happened to Kosovo Albanians,” Policy Paper no. 1/16 (Pristina: Kosovar Institute for Policy Research and Development, June 2016), www.kipred.org/repository/docs/What_happened _to_Kosovo_Albanians_740443.pdf.

42. Renate Ysseldyk, Kimberly Matheson, and Hymie Anisman, “Religiosity as Identity: Toward an Understanding of Religion from a social Identity Perspective,” Personality and Social Psychology Review 14, no. 1 (February 2010): 60–71.

43. Marc Sageman, “Understanding Terror Networks: The Turn to Political Violence” (London: The Henry Jackson Society, July 13, 2010).

44. Sophie Namy, Brian Heilman, Shawna Stich, and Jeffrey Edmeades, “Be a Man, Change the Rules: Findings and Lessons from Seven Years of CARE International Balkans’ Young Men Initiative” (Washington, DC: International Center for Resarch on Women, 2014).

45. Besnik Bislimi, “Deradicalization, Mission (Im)possible,” Radio Free Europe, September 10, 2016, www .evropaelire.org/a/27979187.html.

46. Telegrafi.com, “Images from Hasani family from Kosovo to ISIS,” http://telegrafi.com/pamje-te-familjes-hasani -nga-kosova-qe-gjenden-ne-isis-fotovideo/.

47. Scott Atran, Talking to the Enemy: Religion, Brotherhood, and the (Un)making of Terrorists (New York: HarperCollins, 2010).

About the Author

Adrian Shtuni is the Principla Consultant at Shtuni Consulting and focuses on the Western Balkans as well as the eastern Mediterranean. He consults on countering violent extremism (CVE), counterterrorism, political risk, irregular migration, and other transnational threats. He also designs and implements CVE trainings and programs, and regularly presents at national and international conferences, summits, and symposiums.

For more information on issues and events that shape our world, please visit the CSS Blog Network or browse our Digital Library.