Does Reconciliation Prevent Future Atrocities? Evaluating Practice in Sri Lanka

13 Oct 2017

By Kate Lonergan for United States Institute of Peace (USIP)

This article was external page originally published by the external page United States Institute of Peace (USIP) on 27 September 2017.

Summary

- Reconciliation and atrocity prevention are often assumed to complement and reinforce each other in peacebuilding. Evidence shows that countries with a violent past are at increased risk of future atrocity, and reconciliation practice seeks to build relationships destroyed by violence. The logic of atrocity prevention through reconciliation in countries that have previously experienced widespread violence remains largely untested, however.

- Sri Lanka’s long history of violence and atrocities increases the risk for atrocity to recur. Based on a randomized experiment and qualitative analysis in-country, this report finds that reconciliation practices in Sri Lanka may serve only a limited immediate purpose in preventing mass atrocities, but lays the groundwork for long-term mitigation of atrocity risk.

- Some institutional reconciliation efforts in Sri Lanka have addressed atrocity risks at the national and intergroup level, but require credible promises and full implementation of proposed policies.

- The interpersonal reconciliation practice tested through a randomized field experiment at the University of Colombo may have limited impact on attitudes related to atrocity risk due to a short program timeline and the risk of selection bias.

- The study illustrates the significant challenges facing efforts to evaluate atrocity prevention practice—among them how widely the findings of one case study can be applied, establishing valid and accurate survey questions to measure attitudes, and isolating the effects of institutional mechanisms and determining causality.

- By understanding, beyond assumptions and anecdotal impressions, the conditions under which reconciliation can best help reduce the risk of future atrocities preventive practice can more effectively achieve lasting peace following violent conflict.

Introduction

In the aftermath of atrocity, societies often struggle to build lasting peaceful relationships for the future. When communities formerly in conflict are forced to live together as neighbors or colleagues and feelings of guilt, fear, resentment, or anger remain deeply rooted, the risk of tensions flaring up again is significant.

It seems logical that reconciliation practice, intended to build peaceful and constructive relations between communities previously in conflict with one another, would also be a preventive measure against the rise of mass violence and atrocity in the future. However, much is unknown about the effects of current reconciliation practice on the likelihood of future atrocities. A growing body of research assessing the impact of reconciliation interventions finds that they can improve trust, empathy, social cohesion, and positive attitudes toward the other.1 However, little existing research explores the effects of reconciliation mechanisms on the risk of future atrocity.

This report, using Sri Lanka as a case study, investigates the extent to which different approaches to reconciliation can contribute to long-term structural prevention measures against atrocity. By understanding, beyond assumptions and anecdotal impressions, the conditions under which reconciliation can best help reduce the risk of future atrocities, peacebuilding practice will be better placed to achieve its goal of lasting peace after violent conflict.

The relationship between reconciliation and atrocity prevention in Sri Lanka highlights both practice and risk. Cycles of violence and atrocity have repeated in Sri Lanka since its independence in 1948, making it a relevant case against which to assess post-atrocity response as preventive action. Various reconciliation efforts have arisen in response to these atrocities, including an ongoing effort to address the twenty-six-year largely ethnic conflict between the minority separatist group Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE) and the largely Sinhala majority Sri Lankan army. The Sinhala majority are primarily Buddhist and make up roughly 75 percent of the population; the Tamil minority are primarily Hindu and make up roughly 15 percent of the population. The remaining 10 percent is largely Muslim.2 Both national and grassroots reconciliation initiatives to address the legacy of this conflict exist, but have largely operated separately, allowing for analytical separation of the effects of two types of reconciliation mechanisms.

For this report, atrocities are defined as genocide, crimes against humanity, and war crimes—following the definition used in the UN’s Framework of Analysis for Atrocity Crimes, from which risk measures are derived in this analysis.3 Atrocity crimes typically refer to the legal formulations of such acts. Mass atrocity generally refers to the same acts but does not impose specific legal definitions. This term, given its broader scope and more generous definition, is more widely used in policy and practice.4 In this report, the terms atrocity, atrocity crimes, and mass atrocity are used interchangeably.

What Are Atrocity Crimes?

- Genocide: systematic violence committed with the intent to destroy members of a national, ethnical, racial, or religious group on the basis of their membership in that group

- Crimes against humanity: widespread and systematic violence against civilians

- War crimes: violence against the wounded and sick, prisoners of war, and civilians during wartime

Source: UN Framework of Analysis for Atrocity Crimes.

Reconciliation

Reconciliation efforts aim to rebuild and repair society following violent conflict and to foster more peaceful relationships between formerly conflicting groups. After violent conflict and mass atrocity, reconciliation has the potential to transform identities once defined by conflict into ones defined by peace.

Reconciliation can come about in various ways. One approach involves creating institutional mechanisms and policy changes that support the development of peaceful intergroup relations. Another uses interpersonal encounters to bring people from formerly conflicting identity groups together to directly foster positive contact and build more peaceful individual relationships. Both approaches are characterized by certain core principles. These include the ability of different groups to coexist and resolve disputes peacefully, inclusive identities defined by peace rather than conflict, trust between individuals and groups in society, empathy for others, and mutual acknowledgment of past events. Although this process is not linear, each component involves differing levels of ambition and builds on processes developed in other components.

Coexistence helps facilitate the process of building more peaceful and respectful relationships. For former enemies to begin the challenging work of building more peaceful and respectful relationships, the first step is a basic expectation that the groups can live together peacefully and resolve conflicts nonviolently. Reconciliation efforts in the midst of conflict can help humanize and empathize with members of the conflicting group, but ongoing large-scale violence poses a consistent threat to these efforts by further entrenching conflictive identities. At the broadest level, coexistence means that all parties agree to resolve disputes through rule of law and inclusive institutions rather than through violent conflict. This agreement sets the stage for dialogue, cooperation, and peaceful relations between groups. At the individual level, coexistence involves a commitment to nonviolent resolution of disputes between individuals. Although coexistence alone cannot achieve reconciliation, more substantive efforts will be most effective when formerly conflicting parties can live together peacefully and begin to address the violent legacies of the past.

Identity is a core catalyst for much intergroup violence and thus developing an inclusive identity becomes a core component of reconciliation. Conflicts often arise when divisions between an in-group, those with similar identifying characteristics, and an out-group, those with different identifying characteristics, become too polarized and negative.5 If conflict arises from a clash between identities that have been constructed in opposition to each other and defensive reactions to protect one’s positive self-identity, then the process of recovering from conflict must shift these harmful patterns. Inclusive identity is one of the more ambitious components of reconciliation, and skeptics question whether it is ever fully possible to change entrenched social identities in a post-atrocity society. However, many examples exist of incremental shifts in identity salience. For example, a sports program in Cyprus brings together Greek Cypriot and Turkish Cypriot youth to form basketball teams.6 Their identities as teammates supersede their ethnic identities during these games.

Trust is another core aspect of reconciliation. Conflict is characterized by mistrust between groups and between individuals.7 Interpersonal conflict is the result of broken trust, whereas intergroup conflict occurs as a result of fractured relationships and trust between collectivities. If trust is not established at the outset of a reconciliation process, maintaining effective communication and building strong relationships throughout the process is more challenging. Trust sets the stage for the types of interactions that can lead to the development of more positive relationships between formerly conflicting groups. Trusting relationships also encourage active cooperation between them. Trust allows individuals to be receptive to other elements of reconciliation and to open space to redefine conflictual identities.

Empathy can help restore humanity that has been diminished over the course of mass violence and allows for consideration of another group’s needs and interests.8 Over the course of violence and atrocity, the enemy often becomes dehumanized, portrayed in a way that strips away their unique human qualities. Dehumanization is considered a risk factor and preparatory stage for mass atrocity.9 Empathy can develop through activities that share a different perspective or experience of life than one’s own, such as learning about different cultural events and traditions. At a more emotional level, it involves the ability to connect to what another person is feeling and experiencing and respond accordingly. For example, a dialogue club program in Rwanda brought together survivors, ex-prisoners, ex-combatants, and youth to share stories of their conflict experiences. Hearing these experiences from a different perspective has helped participants process their trauma and reconcile with those who have caused them harm.10

Mutual acknowledgment requires reexamination of the narratives and assumptions that have fueled past conflict identities. This process both recognizes that societal values were violated and restores the individual sense of worth that was destroyed through a violent act.11 If the underlying narratives that fueled conflict are not addressed, discord and grievance are likely to continue under the surface and can threaten to unravel other elements of reconciliation.

Truth is one component of mutual acknowledgment. Although the formal establishment of truth is often treated as an outcome of reconciliation in its own right, at the interpersonal level the more important aspect is that individuals are able to achieve meaningful acknowledgment and validations of experiences and feelings.12 In South Africa, for example, the Truth and Reconciliation Commission offered acknowledgment of abuses that had long been hidden or minimized. Formalized truth efforts are common, but mutual acknowledgment can begin through person-to-person encounters such as dialogue and other collaborative activities even in the absence of a larger process of establishing officially agreed-upon truth.

Reconciliation in Practice

In practice, reconciliation can take many forms. Building peaceful relationships and transforming conflict identities happens at all levels of society, and thus needs to be addressed from different angles. At the broadest delineation, reconciliation can be divided into institutional or interpersonal processes.13 Institutional reconciliation efforts aim for change at the structural level through law or policy, whereas interpersonal reconciliation focuses on the individual level. Both levels of reconciliation interact to facilitate a holistic societal transformation toward peace.

Institutional approaches to reconciliation try to work from the top down, using formalized institutions, laws, and policies to build vertical relationships between the state and citizens in a way that encourages more peaceful relations.

The most common institutional approach to reconciliation is a truth and reconciliation commission. Such entities are a formalized mechanism through which to share accounts of mass violence and atrocity and establish an official version of what happened during a conflict. Establishing truth provides both mutual acknowledgment of past suffering and a starting point for political and social change to address legacies of identity divisions and violence. The recommendations of a truth commission, if followed, create the opportunity to rebuild trust between the people and state institutions that may have perpetuated violence. South Africa is perhaps the best-known and most influential example. Truth commissions have also taken place elsewhere around the world: thirty-three have operated in places as diverse as Solomon Islands, Kenya, and Guatemala.14

In the absence of a full truth commission, incremental steps toward institutional reconciliation can occur in other ways. Changing individual laws or policies that perpetuate identity-based discrimination, dehumanizing rhetoric, and hate speech can send a powerful signal from leaders that this behavior is not acceptable. For example, legislation can impose penalties for identity-based discrimination in hiring or university admissions, systemic hate speech can be criminalized, or requirements for proportional representation based on ethnicity can be introduced to the political system.

The goal of interpersonal reconciliation is to build relationships between individuals that will then influence broader peaceful relations between formerly conflicting groups. This approach starts from the grassroots level in hopes that positive contact and individual relationships will create a foundation of peaceful interaction to guard against the emergence of violent conflictual identities at the group level.

A variety of approaches are used to build more peaceful relationships and reconcile. These can include individual apologies, trauma healing, mediation, joint development projects, and documentation of history.15 However, the most common mechanism is an interactive program that brings individual members of formerly conflicting groups together to build positive relationships and reduce animosities between them through a dialogue process.16 Contact- and dialogue-based programs bring together a wide variety of community members to engage in interactive activities that build intergroup trust, facilitate healing, encourage respect between former enemies, and foster empathy. Activities can range from direct dialogue to arts, sports, or cultural exchange. These strategies are designed to create personal changes in attitudes and behaviors among participants that will then extend into society. Cooperative forms of contact can also create a common in-group identity, such as a national one, that brings together members of different ethnic and religious groups.

Most postconflict societies pursue both institutional and interpersonal approaches in a holistic effort to build peaceful relationships. If done right, both levels can complement and reinforce each other, addressing different issues and using the strengths of different actors. In reality, efforts run the risk of becoming disjointed and missing opportunities for collaboration. State and grassroots actors may proceed on parallel tracks yet have little opportunity to work together. Consequently, institutional-level mechanisms may not adequately reflect the concerns and ground realities of the people they are meant to serve. Conversely, grassroots efforts that receive no institutional support may lack legitimacy and reach. The nonlinear nature of reversing conflict attitudes and building relationships makes some level of this unavoidable. Under ideal conditions, a coherent and collaborative reconciliation practice that brings together multiple mechanisms and theories of change is best placed to produce lasting change.

Atrocity Prevention

As a dedicated peacebuilding practice, atrocity prevention has gained significant ground in recent decades, as it inched forward from theory to practice. The massacres and large-scale violence perpetrated against unarmed civilian populations in the previous century, from the Nazi Holocaust to the massacre of Muslim Bosniaks in Srebrenica to the mass killing of Tutsi by Hutu neighbors in Rwanda, were important wake-up calls to the international community, encouraging the creation of new institutions, legal frameworks, policies, and field operations. The drivers and triggers that may advance the risk of or spark mass atrocities are increasingly understood, and political commitments have been made to prioritize the prevention of these crimes at various international forums. Yet still, the recent violence in the Central African Republic, Syria, and Burma illustrates that serious risk of atrocities still remains in many parts of the world. Significant room for progress remains to improve the atrocity prevention capabilities of international organizations, civil society, and political regimes.

Prevention can take many forms and happen at many stages before an atrocity. A 1997 report by the Carnegie Commission differentiates between operational and structural prevention for all types of violent conflict. This distinction is also relevant to atrocity prevention efforts. Operational prevention is a short-term response to prevent imminent mass violence, halt ongoing atrocities, or mitigate its impact. These efforts aim at immediate impact through strategies such as sanctions, preventive diplomacy, or mediation.17 Structural atrocity prevention takes a longer-term approach, aiming to address the underlying causes of mass atrocity long before they erupt. Given the conceptual overlap with reconciliation practice, this report focuses on structural prevention and ways to mitigate long-term atrocity risks.

Structural prevention efforts focus on changing the social and political factors that make atrocities more likely to occur, such as discrimination, divisive economies, weak accountability institutions, and access to the means to commit atrocity crimes.18 International actors often dominate the atrocity prevention field, but the primary source of structural prevention lies with national actors, at both the state and the grassroots level.19 Although often politically difficult to implement, long-term structural prevention is an important first line of defense against escalating violence and the outbreak of mass atrocities.

Assessing Risk

Effective prevention depends on addressing emerging crises before they escalate. Prevention efforts need to be targeted at areas at risk for atrocity, whether in the long term or the short term. Predicting the outbreak of atrocity is challenging and imprecise. Despite the challenges of early warning efforts, they are a first step in ensuring that atrocities do not occur. The earlier atrocity risk can be identified, the more options are available for prevention. Responses can be tailored to context-specific needs and to directly address the areas of highest risk.20

Research into the causes of mass atrocity has grown considerably in recent decades. Some scholars examine large-sample, cross-country analyses of macro-level influences on genocide. Others focus on understanding why individual perpetrators participate in mass atrocities.21 These findings have coalesced into a wide body of knowledge on the risk factors that make atrocity crimes more likely. To carry out an atrocity, risk factors must combine in a way that provides both the means and motivation to carry out large-scale targeted violence.22

Different international organizations, think tanks, and civil society organizations have developed tools to measure and assess atrocity risk.23 One of the most comprehensive compilations at both the structural and operational level is, as mentioned earlier, the UN Framework of Analysis for Atrocity Crimes.

The framework reflects the latest research on causes of atrocity crimes and supports the UN’s early warning mandate. Risk factors include eight relevant to all types of atrocity crimes, and two each specific to genocide, crimes against humanity, and war crimes (see box 1). Specific indicators then describe ways in which a particular risk factor has developed or manifested in past atrocity situations. Atrocity crimes are an extreme form of violence and usually result from an escalatory cycle. However, the process is not always linear and atrocity crimes are not inevitable under conditions of risk. Not all indicators need be present to constitute the existence of risk. Likewise, not all risk factors need be present for an atrocity to occur.

Box 1. Risk Factors for Atrocity Crimes

1. Situations of armed conflict or other forms of instability

2. Record of serious violations of international human rights and humanitarian law

3. Weakness of state structures

4. Motives or incentives

5. Capacity to commit atrocity crimes

6. Absence of mitigating factors

7. Enabling circumstances or preparatory action

8. Triggering factors

9. Intergroup tensions or patterns of discrimination against protected groups

10. Signs of an intent to destroy in whole or in part a protected group

11. Signs of a widespread or systematic attack against any civilian population

12. Signs of a plan or policy to attack any civilian population

13. Serious threats to those protected under international humanitarian law

14. Serious threats to humanitarian or peacekeeping operations

Source: UN Framework of Analysis for Atrocity Crimes.

Reconciliation as Prevention

Structural atrocity prevention efforts aim to reduce sources of grievance or encourage peaceful resolution of disputes when the risk of violence is still remote. Reconciliation presents a promising structural prevention instrument in a postconflict environment. Evidence, as mentioned, shows that one of the major predictors of man-made atrocities is a history of conflict and violence.24 Logically, it seems that a process to reconcile from those past atrocities would help break the cycle of violence and prevent future atrocities.

Reconciliation is theorized to prevent future atrocities in two ways: by deterring future perpetrators and increasing resilience to future atrocity risks. When would-be perpetrators see that past incidents of mass atrocity have been largely unaddressed, their inhibitions about participation lessen. Studies of the Rwandan genocide found that the culture of impunity following previous atrocities reduced the sense of risk that perpetrators felt during the 1994 genocide.25 Not addressing the past also fuels denial of mass atrocities and allows perpetrators to justify their violence. Reconciliation processes that involve confronting the past, even at the interpersonal and nonpunitive level, can help inhibit the cycle of impunity and reoccurrence.

Reconciliation practice also addresses some of the core risk factors for mass atrocity, such as intergroup tensions, identity-based polarization, dehumanization, and grievances over unacknowledged past victimization. Thus, it seems that a reconciliation process that addresses these would increase resilience against future atrocity.26 By healing and restoring relationships between former adversaries, the reconciliation process can reduce the tensions that contribute to risk. This has proven relevant in Zambia, where risk factors have been mitigated by policies that constructively manage diversity and intergroup tension.27 Reconciliation processes can also address the risk that perceived victimization can lead groups to feel vulnerable and defensive, and more likely to resort to violence for self-protection.

These theoretical links aside, reconciliation also involves the potential to resurrect old grievances and destabilize a fragile peace. Some feel that forgetting is the best way to establish peaceful relations between former enemies and that directly confronting the past and demanding accountability will in fact hasten the cycle of renewed violence and atrocity. These conflicting stances necessitate further examination and empirical investigation of the relationship between reconciliation and atrocity prevention.

Limited empirical evidence exists on the conditions under which reconciliation activities can contribute to reducing atrocity risks. The current understanding of the links between these practice areas hinders the ability of these initiatives to positively reinforce mutual goals. Assessing the impact of institutional and interpersonal mechanisms of reconciliation in Sri Lanka on relevant indicators of atrocity risk clarifies these conditions.

Sri Lanka

Sri Lanka is representative of both the successes and challenges of reconciliation and atrocity prevention at both the institutional and interpersonal levels. The links between reconciliation and prevention are relevant to current policy debates in the country, making it a timely case for further study. Sri Lanka recently launched renewed efforts toward national unity and reconciliation, ushered in with the election of President Maithripala Sirisena in 2015. This process focuses on four pillars of transitional justice: truth, justice, reconciliation, and nonrecurrence. As the national reconciliation process develops, understanding how reconciliation and nonrecurrence overlap is critical.

Institutional reconciliation efforts have focused on policy-level changes to address conflict legacies and involve state actors. Interpersonal efforts have taken place at the grassroots level, driven primarily by civil society and religious organizations. Until recently, these approaches in Sri Lanka have largely proceeded along parallel tracks. This division makes it easier to discern the effects of each approach. More recent national efforts have begun to blur these lines. State-sponsored reconciliation programs were proposed at the community level but not yet widely implemented at the time of research.

Although the Sri Lankan legacy of reconciliation efforts is uneven, the challenges are representative of those in many postconflict situations. Reconciliation is complex and nonlinear, often beset by resistance, implementation delays, and disconnect between national and grassroots processes.

Sri Lanka’s long history of violence and atrocities, carried out largely with impunity, increases the risk for atrocity recurrence. In the 1970s and 1980s, a Marxist Sinhala youth movement known as Janatha Vimukthi Peramuna staged two uprisings against the government in the southern part of the country. Their brutal attacks on police, state officials, and civilians were met with even harsher responses from the Sri Lankan army, resulting in somewhere between forty thousand and one hundred thousand deaths.28

The longest-running violent conflict has been ethnic based, between the majority Sinhala and minority Tamil ethnic groups. Tensions between the two groups have a long history, but its modern iteration emerged from the British colonial period, when Tamils found favor. Immediately after independence, the Sinhala majority sought to reassert its privileges. Violent clashes between ethnic Sinhala and Tamil citizens broke out soon after independence, in 1956, and continued sporadically over the following decades as political attempts to address the root issues of minority rights and representative power faltered. In July 1983, between 140 and six hundred Tamil citizens were killed in violent riots spurred in part by the killing of thirteen Sinhalese soldiers by the LTTE, an armed Tamil insurgency group that arose to fight for a separate Tamil state on the island.29 This event, Black July, is often referred to as the start of the twenty-six-year civil war fought between the separatist LTTE and the government of Sri Lanka. This period witnessed significant attacks against Sinhala, Tamil, and Muslim ethnic communities on the island, displacement, disappearances, and human rights abuses. The military defeat of the LTTE in May 2009 was accompanied by alleged war crimes committed by both sides against Tamil civilians.30

Threats and violent attacks against the country’s Muslim minority have increased in recent years, often fueled by extremist Buddhist groups. Targeted attacks against Muslims erupted in the southern coastal town of Aluthgama in 2014, killing three and injuring seventy-eight. These attacks were promoted and publicized by Bodu Balu Sena, an extremist Buddhist group, using social media accounts. These incidents highlighted underlying tensions and the rise of hate speech and inflammatory rhetoric and further exacerbated ethnic divisions.31 Addressing the legacy of atrocities and preventing future violence is a major challenge now facing Sri Lanka.

Efforts to reconcile conflicting groups in Sri Lanka have had mixed results. Most common were grassroots programs designed to foster dialogue and build trust between groups whose identities have been shaped by conflict. These include interfaith dialogue groups and exchange programs between students from ethnically homogenous areas. Within an environment of conflictual rhetoric, grassroots dialogue programs in Sri Lanka have tried to build lasting relationships across communal divides.

Other approaches focused on the structural level, establishing institutions or policies that foster more positive intergroup relationships. The 2010 Lessons Learnt and Reconciliation Commission (LLRC) was a starting point for implementing institutional reconciliation mechanisms. It issued several hundred recommendations, which were seen as a hopeful starting point for reconciliation work but have been only slowly implemented. Numerous commissions of inquiry have also investigated injustices and violations over the course of the post-independence period.32 Although both approaches have been criticized for their limited scope, they demonstrate some state effort to address calls for accountability.

Recent political developments have brought renewed attention to reconciliation and accountability for past violence. In 2015, Maithripala Sirisena defeated former president Mahinda Rajapaksa, who had been elected in 2005 and had led the country through its military victory over the LTTE. Rajapaksa’s presidency was an era of increasing executive power and controversial decisions in the postwar period that many believed ultimately set back the process of reconciliation rather than advancing it.

Sirisena was elected on a broad platform of good governance and national unity, laid out in campaign promises for his first hundred days that included limitations to executive power, reduction in high living costs, election reform, and corruption investigations.33 In contrast to his predecessor, Sirisena has made credible pledges to pursue national reconciliation, although implementation of these pledges has been slow. He established the Office of National Unity and Reconciliation (ONUR), which is responsible for developing a national policy on reconciliation and promoting national unity. On its inception, the ONUR established the Consultation Task Force to inform this policy and sponsored forums and public events championing reconciliation and unity.34 Sirisena has already initiated some reconciliation measures, from establishing the Office of Missing Persons to investigate conflict-era disappearances to playing the national anthem in both Sinhala and Tamil on Sri Lankan Independence Day in 2016.

Sirisena also opened new opportunities for postconflict justice and accountability. The UN Office of the High Commissioner on Human Rights (OHCHR) released a long-awaited report in September 2015 on alleged international crimes and human rights abuses committed in the conflict between the government of Sri Lanka and the LTTE between 2002 and 2011. This report documented a wide range of abuses and concluded that evidence existed of systematic violations of international law and human rights from both parties to the conflict.35 The resulting UN resolution called for, among other actions, a hybrid special court comprising Sri Lankan and international adjudicators to investigate and try war crimes and crimes against humanity.36 Former president Rajapaksa strongly resisted this investigation; President Sirisena has taken a more cooperative approach. A March 2017 update on Sri Lanka’s progress included in the OHCHR annual report concluded that encouraging steps have been taken toward reconciliation and transitional justice, but slow progress on implementing proposed measures and establishing accountability frameworks threatens to compromise the initial momentum.37

Institutional Reconciliation

To investigate the impact of institutional-level reconciliation mechanisms on atrocity risk, the outcomes of selected LLRC recommendations were assessed against relevant indicators.

Six recommendations were chosen for evaluation based both on reasonably robust progress on implementation and relevance to the current debates around reconciliation policy in Sri Lanka. They include: singing the national anthem in both Tamil and Sinhalese, allowing inclusive conflict memorialization, establishing institutions of accountability, resettling displaced Muslim families in northern Sri Lanka, and returning military-occupied civilian land. Although critiques were made against the mandate and structure of the LLRC, the resulting recommendations were generally seen as a hopeful contribution to long-term reconciliation efforts. Many civil society actors have taken them as a starting point for advocacy efforts and continue to advocate for fulfillment of the recommendations. The current renewed national reconciliation process also intends to build on recommendations made in the LLRC, making it a useful starting point for future work on institutional-level reconciliation.

This assessment drew on a variety of secondary sources to determine whether indicators of atrocity risk improved after the reconciliatory institutions and policies were implemented. Secondary sources include newspaper articles, public statements from politicians and leaders, national-level survey data, and civil society reports.

The LLRC mandate—which included investigating events related to the ethnic conflict between the Sri Lankan army and the LTTE—included five areas of focus: the failure of the 2002 ceasefire agreement, responsibility for the failure, lessons learned, restitution for those affected, and measures for nonrecurrence of conflict in Sri Lanka.38

The LLRC was a promising opportunity for those seeking information about loved ones who had died or disappeared during the conflict.39 Input to the investigations was invited from a wide range of stakeholders, including the public and civil society. Public hearings were held across the country, including in areas most affected by the conflict.

Amid optimistic participation, the commission faced many critics. Some civil society organizations declined to participate in the process, citing serious concerns around the impartiality of the commissioners, the investigation methodology, and the witness protection measures.40 Others focused on the mandate of the LLRC, arguing that it did not provide for investigations of individual accountability for violations of international humanitarian law. Past commissions and investigations in Sri Lanka had amounted to little action, thus limiting public trust in the efficacy of government-led initiatives to establish truth and accountability. Although the structure and scope fell short of the ideals pushed for by advocates, the resulting recommendations received less criticism. Citizens and civil society organizations alike expressed measured appreciation for the substance of the report and inclusion of controversial issues in both the analysis and recommendations.41

The final LLRC report, released in December 2011, included 285 recommendations across five thematic areas: international humanitarian law violations, human rights, land issues, restitution, and reconciliation.42 An additional fifty-eight recommendations were added in 2013, mostly related to land issues.43 Implementation has thus far been piecemeal. In January 2014, the government of Sri Lanka declared that some of the recommendations had been completed.44 Independent analyses have cast doubt on these claims, however, finding that some of those represented as completed actually fell short in practice or did not adequately reach affected communities.45

Despite the structural shortcomings and limited implementation, the LLRC remains the primary reconciliation document in Sri Lanka. It identifies sound recommendations within the constraints of its mandate, and many international organizations and civil society organizations have taken these recommendations as a starting point to advocate for transitional justice, reconciliation, and redress for victims.46

Measuring Risks

Institutional interventions, whether policy or organizational, create structures that limit risk and encourage resilience to atrocity, thus providing a long-term preventive strategy. Specific indicators were drawn from the 2014 UN framework (see table 1).

A lack of trust in state institutions poses an atrocity risk because it hampers the ability of different groups to coexist peacefully, limits accountability for past actions, and undermines the ability of the state to adequately protect against future violence. State institutions provide a peaceful forum for conflict resolution and a framework to address grievances without resorting to violence. When local dispute resolution mechanisms or the court system are seen as trustworthy and accountable, then the inevitable rise of conflict and grievance can be dealt with collaboratively and in accordance with the rule of law. Historical failure of state institutions to peacefully address disputes and avert larger violence signals that these institutions are untrustworthy, and decreases the likelihood that they will be used to peacefully address conflict in the future.

Accountability lowers atrocity risk by signaling that such violence will not be tolerated. When accountability is absent, would-be perpetrators may learn that mass violence is a strategic approach to achieving their goals, and will not carry significant deterrent consequences. Institutions that provide accountability for violations are expected both to provide these deterrent effects and to increase societal trust in institutions.

Table 1. Selected Institutional and Policy-Level Atrocity Risks

- 2.8 Widespread mistrust in state institutions or among different groups as a result of impunity

- 3.6 Absence or inadequate external or internal mechanisms of oversight and accountability, including those where victims can seek recourse for their claims

- 4.3 Strategic or military interests, including those based on protection or seizure of territory and resources

- 4.9 Social trauma caused by past incidents of violence not adequately addressed and that produced feelings of loss, displacement, injustice, and a possible desire for revenge

- 9.2 Denial of the existence of protected groups or of recognition of elements of their identity

- 9.4 Past or present serious tensions or conflicts between protected groups or with the State, with regards to access to rights and resources, socioeconomic disparities, participation in decision-making processes, security, expressions of group identity, or to perceptions about the targeted group

Source: UN Framework of Analysis for Atrocity Crimes.

A heavily militarized society can make the tools to commit mass violence more accessible, either to state actors or to other groups who can forcibly gain access to military assets. Limiting military presence in civilian areas and reducing the flow of small arms can create logistical barriers to carrying out mass violence. Creating these barriers can help control overall risk even when motivations to commit atrocity crimes rise.

Widespread social trauma and feelings of injustice can, particularly when experienced at the group level, fuel grievances and animosity between identity groups.47 Under certain circumstances, this animosity and desire for revenge can escalate to violence. This is a continuous pattern in Sri Lanka: multiple groups have used violence to achieve their goals, but little meaningful change has resulted. Narratives of injustice and the emotional burden of oppression and social trauma have thus continued, heightening the risk of violence and atrocity.

Identity-based tensions are a major underlying factor of atrocity risk. Although tensions are often seen only as relationships between individuals, divisions between identity groups are influenced at the institutional and policy level as well. Discriminatory policies can limit the opportunities available to minority groups, creating horizontal inequalities between minority and majority citizens. This can fuel grievances that lead to conflict, and can in turn influence atrocity risk. More subtly, institutions and policies can exhibit bias toward a particular identity group. Reducing overt or subtle discrimination can help limit the motivations to carry out an atrocity.

LLRC Recommendations

Changes in relevant atrocity risk indicators were measured against six key recommendations laid out in the LLRC (see table 2). An implementation date was determined for each recommendation. Relevant indicators of atrocity risk were then measured before and after the date to assess progress. The extent to which the recommendation was implemented was examined first, and then whether the type of change in atrocity risk that would be expected if reconciliation measures do in fact reduce atrocity risks in accordance with their theory of change.

Singing the national anthem in both Tamil and Sinhalese is an important symbolic gesture that acknowledges the diversity of Sri Lanka and indicates acceptance of Tamil-speaking communities into the Sri Lankan national identity. The importance of a multilingual national anthem is underscored by historic restrictions that favored the Sinhalese language and identity.

Table 2. Key Institutional Recommendations

- 9.277 “The practice of the National Anthem being sung simultaneously in two languages to the same tune must be maintained and supported.”

- 9.285 Set aside a separate event on National Day to express solidarity and empathy with all victims of the tragic conflict and pledge our collective commitment to ensure that there should never be such blood-letting in the country again.

- 9.218 and 219 Establish an independent institution with a strong investigative arm to address the grievances of all citizens, in particular the minorities, arising from the abuse of power by public officials and other individuals involved in the governance of the country. Ensure that any citizen of this country who has a grievance arising out of any executive or administrative act, particularly those based on ethnicity or religion, should have the right to seek redress before the independent institution.

- 9.194 and 195 Facilitate the early return of the displaced Muslims to their places of origin in the Northern Province. Take immediate steps to assist in rebuilding of the mosques, houses, and schools destroyed or damaged by the LTTE.

- 9.14 Review the two existing high security zones in Palaly and Trincomalee-Sampur, as well as small extents of private land currently utilized for security purposes, with a view to release more land while keeping national security needs in perspective. Complete the provision of alternate lands and/or payment of compensation within a specific time frame.

Source: Report of the Commission of Inquiry on Lessons Learnt and Reconciliation, November 2011.

Language in Sri Lanka is intimately related to identity and ethnic divisions. The Sinhalese majority ethnic group and Tamil (and Muslim) minority groups largely speak different languages. In 1956, Sinhala was made the sole official language, marking the beginning of increasingly discriminatory policies and attitudes against Tamil-speaking minorities.

In 2010, then president Rajapaksa issued an unofficial ban on singing the national anthem in Tamil.48 In March 2015, President Sirisena called for a reversal and during Independence Day celebrations in February 2016 the national anthem was sung in Sinhala and Tamil for the first time since 1949.49 Implementing this recommendation required support from leadership at the highest institutional level to signal a more inclusive national identity and state.

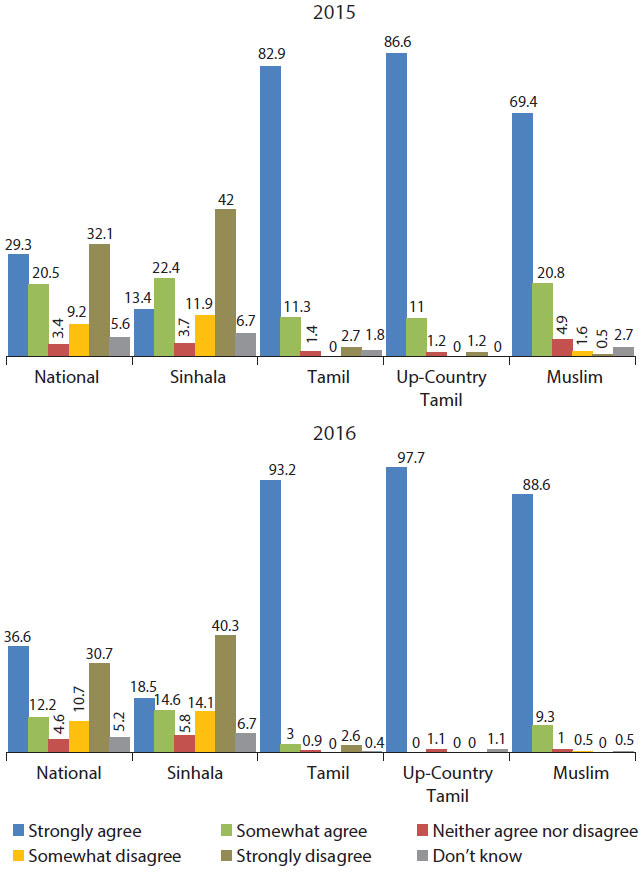

Public opinion polls show intensified support for this policy since its implementation in February 2016.50 Opinion was mostly in favor in June 2015, before the change was implemented, but ethnic disaggregation shows that support largely fell along ethnic lines. Strongest support came from minority communities: more than 80 percent of Tamils and 70 percent of Muslims. The majority Sinhalese largely opposed the idea: only 13.4 percent agreed with the proposal.

In April 2016, after the change was implemented, 18.5 percent of Sinhalese respondents strongly supported it. Strong support also increased among minority respondents, Tamil respondents at 93.2 percent and Muslim at 88.6 percent. Overall national support also intensified between 2015 and 2016; disapproval rates remained unchanged (see figure 1).

Statements from Tamil leaders reflected the public’s response. After the 2016 Independence Day celebrations, the northern chief minister remarked, “We are very happy that the national anthem was sung in Tamil…if the Sinhalese people take one step forward and move toward the Tamils then the Tamils will take ten steps forward towards the Sinhalese community.”51 His statement highlights the symbolic meaning of this change for reconciliation and relationship building between majority and minority groups in Sri Lanka.

Although the exact causal pathway between a policy change on singing the national 5anthem in Tamil and changes in public opinion around this policy is difficult to determine, correlations between the two are clear. As policy changes were enacted to demonstrate symbolic inclusivity at the highest level, attitudes indicative of group-wide divisions and identity clashes became more positive. Reduced identity divisions at the societal level indicate reduced atrocity risk, providing fewer divisions and negative attitudes that could be a motivating factor to orchestrate atrocity.

Figure 1. National Anthem Support

An inclusive day of remembrance marking the end of the conflict has become a major point of contention in the reconciliation debate in the country. In years immediately following the defeat, May 19 was celebrated as Victory Day for the Sri Lankan Armed Forces, and families of fallen LTTE fighters were banned from commemorating their dead.52 The LLRC recommendation to establish an inclusive day of remembrance is intended to address the animosity that arose around these unequal traditions.

Restricting commemorations of LTTE fighters denied Tamil families a potentially cathartic and healing opportunity to acknowledge and publically mourn. When restrictions such as these are leveled against an entire identity group, trauma and a sense of injustice can develop at the group level. Testimony provided in recent reconciliation consultations underscores the lasting effects of collective grief perpetuated by remembrance efforts that do not acknowledge all experiences.53

After Sirisena was elected in 2015, he declared that the anniversary of the end of conflict would no longer be celebrated as Victory Day but rather as Remembrance Day, acknowledging all those who suffered or lost their lives as a result of the conflict regardless of ethnicity. In addition, Tamil communities in the north and east of the country were allowed for the first time to hold memorial events to commemorate their dead.54 Remembrance Day in 2016 was designed as a cultural celebration rather than a military parade.55 The symbolism of this change represented a move toward celebrating shared cultural elements and acknowledging the suffering of all victims.

Opening space for public commemoration was initially welcomed by observers and represented hopeful prospects for inclusive acknowledgment.56 Despite the official policy shift, in practice memorialization activities in areas formerly under LTTE control remain subject to surveillance and intimidation.57 In 2017, a locally organized commemoration event at the site of the last battle of the war was initially blocked and organizers were summoned for questioning before a modified version of the event was allowed to proceed.58 A more inclusive approach to commemoration is a promising step toward a reduced sense of injustice and trauma at the group level, but continued restrictions risk limiting progress.

The LLRC recommendations addressed the need for robust and credible institutions of accountability. Functioning institutions of accountability can provide a framework to address grievances and conflicts nonviolently, thus reducing a root cause of and potential motivating factor in mass atrocity. They also help provide accountability for past abuses and signal that violence and abuse of power are no longer tolerated.

January through September 2015 is used as a rough time frame of implementation for this policy change. Renewed focus returned to institutions of accountability after the January 2015 election of President Sirisena. Further movement came after the release of the report by the OHCHR Investigation on Sri Lanka in September 2015. Following its publication, the government of Sri Lanka cosponsored a UN Human Rights Council resolution committing it to twenty-five measures designed to deal with the past.

Since Sirisena’s election, several institutions of accountability have been established or strengthened, including the ONUR, the Office of Missing Persons, and a 19th Amendment to the constitution. These institutions have the capacity to reduce atrocity risk by serving as forums through which to address the past and to uphold accountability for rights violations. However, delays in meaningful implementation of work of these institutions threatens to limit their preventive power.

The ONUR was established in January 2015 to coordinate and implement policies and programs to build national unity and reconciliation in Sri Lanka. Recommendations from the Consultation Task Force convened by ONUR include a truth mechanism with a broad mandate and public hearings as well as a hybrid justice mechanism to prosecute war crimes, crimes against humanity, and violation of customary international law.59 The passage in Parliament of the 19th Constitutional Amendment in April 2015 drastically limited presidential powers and set up independent commissions on corruption, human rights, and elections, among others.60 The Office of Missing Persons was launched the following year, in August 2016. It will investigate and document cases of missing persons and offer recommendations for redress and reparations for family members.61

Initial analyses saw these institutions as a fresh start from previous reconciliation efforts and commissions of inquiry that lacked credibility.62 However, as progress has stalled around implementation of the promised work of some of these institutions, particularly the proposed reconciliation mechanisms and the Office of Missing Persons, a growing sense of frustration has called into question the likelihood of substantive change.63 Although much progress is still to be made, the official establishment of these institutions does lay the groundwork for institutional-level reconciliation and atrocity prevention.

Resettlement of displaced Muslim families in the Northern Province was another important recommendation of the LLRC. In 1990, all Muslims were evicted from LTTE’s territory of control in northern Sri Lanka. The families, many of whom had lived in the region for generations and had good relationships with their Tamil neighbors, were given twenty-four hours to vacate their homes. Some fled to nearby Mannar and Puttalam districts, where internal displacement facilities were established. The legacy of this abrupt eviction, according to Muslim religious leaders interviewed in 2015, has been an ongoing obstacle to ethnic relations and reconciliation.

Resettlement of displaced communities, under the purview of the Ministry of Resettlement, began in mid-2010. To date, the government has constructed 2,303 houses to resettle Muslim families from Mannar district. An additional 7,485 plots of land have been designated for resettlement and more are in progress.64 A ministerial review mechanism was also initiated to discuss the resettlement of Muslim internally displaced persons to their places of origin in the Northern Province. This review identified priorities for action, including release of land, resettlement assistance, preparation of lands, and development of common and community infrastructure required to facilitate return. An estimated 16,120 houses are required to resettle the displaced Muslim families.65

The combination of ethnic tensions and economic and social inequalities sustained by protracted displacement of Muslim communities potentially contributes to grievances and atrocity risks. Resettlement efforts show some progress but dissatisfaction with the process threatens to undermine it. Some community members have been frustrated with the speed of resettlement, accusing the Northern Provincial Council, the body in charge of resettlement, with limited engagement.66 These accusations have been linked with ethnic tensions, given that the council is largely Tamil, reflecting the ethnic majority in the area. Continued dissatisfaction with the resettlement process has the potential to increase ethnic tensions rather than to diffuse them. Furthermore, a recent pilot survey of attitudes about resettlement found that nearly half (48 percent) of Muslim internally displaced families surveyed preferred to remain in Puttalam rather than return to their former homes.67 The benefits of resettlement to reducing ethnic tensions and social inequalities will come only if the resettlement process is voluntary and respectful of the wishes of displaced communities. Ignoring their needs risks further compounding dissatisfaction.

Military occupation of civilian land expanded in Sri Lanka throughout the course of the ethnic conflict. The military established numerous high security zones throughout the north and east of the country, using them as bases from which to coordinate military efforts to fight the LTTE. The Palaly High Security Zone, on the Jaffna peninsula, covered thirty-six local divisions and displaced approximately 65,756 people. The Sampoor High Security Zone was established on Sri Lanka’s eastern coast near Trincomalee, covered 4,500 acres, and encompassed twelve local divisions; an estimated 15,648 residents were displaced as a result.68 After the defeat of the LTTE and cessation of violence, many of these zones remained in place. Now, many years after the military threat has diminished, the Sri Lankan army still occupies significant tracts of land throughout former LTTE territory.

The release of military-occupied land can have a twofold impact on atrocity risk. First, it addresses the risk posed by extensive militarization and easy availability of weapons. Committing atrocities requires both means and motivation, and heavy military presence in civilian areas, when combined with other risk factors, can establish the means of carrying out mass atrocities. Second, land release can reduce a source of ethnic tensions. Continued occupation of formerly civilian land by the military has become a key grievance fueling conflict and tensions between minority groups and the government.

Since the LLRC recommendation for release of military-occupied land was issued, some land has been released, but much progress remains to be made.69 Assessing progress on land release is challenged by widely differing estimates from various sources. Government figures state that more than three thousand acres have already been released. They estimate that six thousand additional acres remain to be redistributed in the districts of Jaffna, Kilinochchi, Mannar, and Vavuniya. Rehabilitation and Resettlement Minister D. M. Swaminathan said that around eleven thousand families in the north remain to be resettled.70 The British Tamils Forum claims that sixty-seven thousand acres are still under military occupation and that the new government has released fewer than three thousand (2,565) acres in the north.71 The Centre for Policy Alternatives, a leading think tank in Sri Lanka, reported in March 2016 that some 12,750 acres are still under military occupation.72

Despite the differing estimates, military occupation of land throughout the north and east of the country has decreased since the recommendations were released in 2011. This indicates that the military presence in primarily civilian areas has dropped. In principle, this release of lands can increase opportunities for economic activities and benefits. However, the anticipated impact of these developments on atrocity risk ties both to full implementation of land release and a translation of land availability into increased prosperity for marginalized communities. Although a smaller military presence addresses one element of atrocity risk, the broader impacts of land release policy will have a greater impact on tensions and risks in affected regions.

Across the six recommendations, varying levels of atrocity risk reduction are evident. Policies for a bilingual anthem and inclusive war commemorations had a generally positive effect on recognizing minority groups, easing group trauma, and addressing identity-based divisions. Although largely symbolic, these actions sent powerful signals of acceptance of Tamil-speaking communities into the national identity of the country. These signals, however, must be sustained if they are to substantially contribute to atrocity prevention. Initial action was also taken on establishing institutions of accountability. It is too early to assess the effects of these institutions, but that they exist can still have a positive impact, especially if they are credibly implemented and able to fulfill their mandates. Recommendations around land rights and return have also had a mixed impact. Although empirical progress has been made on return and resettlement, it can be easily overshadowed by perceived injustice and dissatisfaction. This dissatisfaction can fuel tensions and grievances to develop along identity lines. These findings show that the preventive effect of institutional reconciliation policies is closely tied to their public credibility and timely implementation.

For reconciliation policies to build resilience to future atrocity risk, simply initiating these policies is not enough. Structural and leadership support are also key. Support for reconciliation from the leadership level helps shift group-level attitudes and public perception around certain atrocity risk factors. The reconciliation policies examined in this analysis were initiated under different political contexts, which influences how the public interpreted and understood them.

The policy changes that more clearly contributed to lower group tensions and other atrocity risk factors were made after a period of stark political transition and sent clear signals of symbolic inclusivity. President Sirisena was elected on a platform of drastic change from the status quo and cultivated an image of divergence from the previous political climate. This intentional contrast fueled public perception of a change in political context, particularly around reconciliation and transitional justice. After the election, the highest levels of government continued to champion the idea of reconciliation and national unity. This helped legitimize the concept and assure the public that a process of building better interethnic relations would be supported. When made in this climate of broader support for reconciliation, Sirisena’s proposals to sing the national anthem in Tamil, to hold inclusive commemoration ceremonies, and to establish institutions of accountability appeared more credible. When accompanied by swift implementation, these policies did create an incremental shift in atrocity risk. However, after the initial wave of symbolic measures, slow progress on the more substantive work of the proposed institutional-level reconciliation mechanisms has led to growing frustration that threatens to undermine the preventive gains.

Interpersonal Reconciliation

Reconciliation practice also occurs at the grassroots level by building positive personal relationships through direct interaction between individuals from different identity groups. These relationships build trust, understanding, and empathy at the individual level, and are intended to challenge negative stereotypes and shift attitudes toward identity groups as a whole. Such programs—which typically involve dialogue and interethnic exchange—are increasingly common in practice, and engage civil society organizations, grassroots organizations, faith communities, and other formal and informal groups.

Sri Lanka Unites, for example, runs youth-focused Reconciliation Centers across the country, as well as an annual conference that brings together youth leaders from diverse ethnic and religious backgrounds for five days of activities focused on leadership and reconciliation. Interfaith dialogue is another common pathway for grassroots reconciliation initiatives at the community level.73 Such programs report many positive impacts at the micro level. These initiatives can take preventive action at the first signs of rising identity tensions, such as a district interreligious committee initiated by the National Peace Council in Ratnapura did in response to a cricket match dispute that escalated into violence between local groups of Tamil Hindu and Sinhala Buddhist residents.74

The Program

To test the impact of interpersonal reconciliation on relevant indicators of atrocity risk, a representative program of common interpersonal reconciliation practice was tested against a control group. Individual-level atrocity risk factors were compared across groups.

A randomized field experiment and in-depth individual interviews were used to understand how interpersonal reconciliation mechanisms affect atrocity risk. A randomized field experiment is advantageous because it enables determining the causal effects of a reconciliation program and accounting for selection bias.

Carried out in partnership with the Social Scientists’ Association, a Colombo-based civil society organization, the field experiment drew from a random sample of 207 university students at the University of Colombo in Sri Lanka, which site was chosen for its ethnically diverse student body and organizational structures suitable for a sustained five-week reconciliation program. A stratified approach was used to randomly select a sample of approximately 50 percent Sinhala, 25 percent Tamil, and 25 percent Muslim students, roughly reflecting the majority-minority dynamics at the national level. The sample also included 50 percent each men and women. The selection of a university population reflects the trend in reconciliation practice in Sri Lanka to implement programming focused on youth. The university system structure also increased the likelihood of sustained participation.

Program activities represented common reconciliation practice and strove to create ideal conditions for reconciliation and positive contact. Common practices include interactive learning using games, movement, and teamwork; repeated meetings over time; voluntary participation; and shared activities where diverse groups must work toward a common goal. Each session focused on a different component of reconciliation and relationship building. The first session involved team building activities. The next focused on the themes of identity and coexistence, which are initial steps toward recognizing and relaxing polarized social identities and developing relationships defined by peace. The third session concentrated on trust, and the fourth addressed empathy at both individual and intergroup levels. The final session explored the theme of mutual acknowledgment of past wrongs (for more detail, see appendix 1).

Semi-structured interviews, sixteen in total, were conducted with a representative subset of the test group—respondents from the Sinhala, Tamil, and Muslim ethnic groups. These interviews explored how respondents’ experiences in the program transformed their conflictive identities, and provided a more nuanced understanding of the program’s impact.75

At the beginning and end of the program, both groups completed a survey measuring atrocity risk and reconciliation outcomes (see appendix 2). Relevant indicators of atrocity risk were again drawn from the UN framework and adapted to reflect attitudes and behaviors that could be measured at an individual level of analysis. Although the UN framework is built around country-level risk, the attitudes and beliefs of individual citizens can also reflect many structural risk factors.

Most questions were attitude statements answered on a six-point Likert scale where a score of one represented Strongly Agree and a score of six represented Strongly Disagree. Wherever possible, survey questions were drawn from existing measures and adapted to the Sri Lankan and university context.76

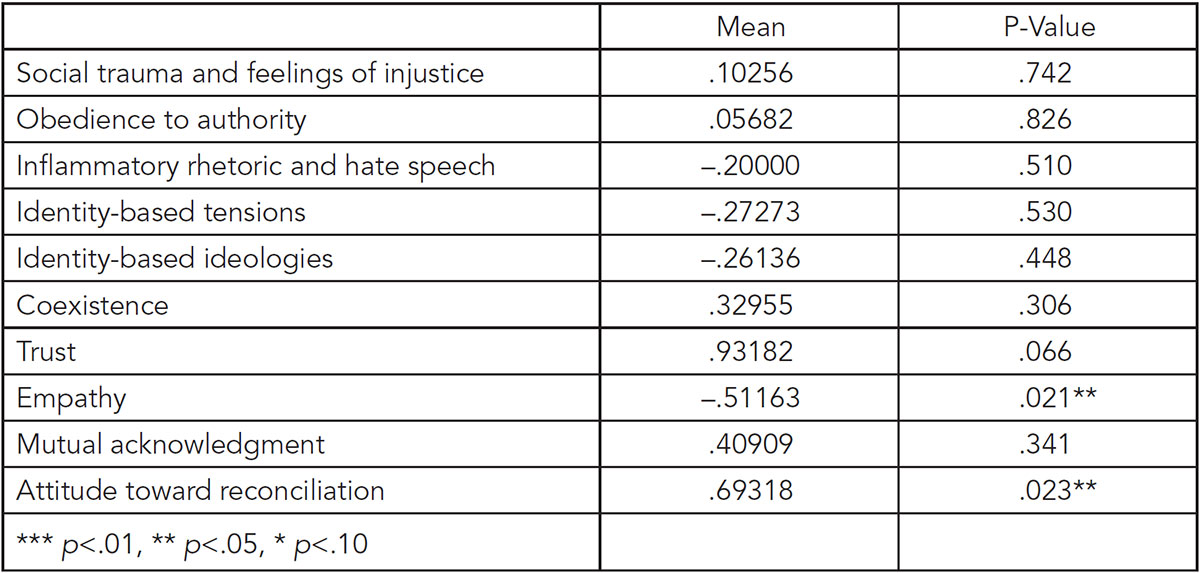

The survey measured attitudes related to five indicators of atrocity risk: social trauma, obedience to authority, inflammatory rhetoric, identity-based tensions, and identity-based ideologies. It also measured six anticipated reconciliation outcomes: identity salience, coexistence, trust, empathy, mutual acknowledgment, and attitudes toward reconciliation processes. Individual questions were combined into an index measurement of each risk factor to capture the multifaceted nature of each risk.

The legacies of personal and social trauma from violent conflict and atrocity can continue into future generations, especially if they are not adequately addressed. When abuses have fallen along identity-based lines, the traumas inflicted on an identity group can also influence attitudes at the individual level. Unaddressed grievances can entrench narratives of conflict, memories of injustices can normalize or justify violence against another group, and lingering trauma can fuel desire for revenge. These effects of social trauma can combine to exclude certain groups from the realm of empathy and justify atrocities.

Carrying out mass atrocities requires the participation and support, whether direct or tacit, of the population at large. One factor that may increase the likelihood that a group will enable mass atrocities to be carried out is a widespread culture of obedience to authority. At the individual level, indicators of an authoritarian orientation can measure this quantitatively. The authoritarian orientation is an individual’s support for societal-level repression and violence.77 Measures focus on the way that an individual relates to the world, and attitudes related to order and hierarchy.78 These beliefs are not immutable on an individual level, but can reflect larger structures and influences that make it more possible to justify violence targeted against particular groups.

Inflammatory rhetoric, hate speech, and dehumanizing language may trigger identity-based violence and atrocity. Individual support for or susceptibility to such rhetoric is indicative of fertile ground for violent mobilization. Hate speech and dehumanizing language portray a particular identity group as beyond human connection, and thus not worthy of the typical moral restrictions and considerations that limit violence.79 The victim loses legitimacy, value, and worth in the eyes of the perpetrators. The development of these beliefs that exclude members of a particular group from the universe of moral concern and reduce moral barriers to violence can increase the likelihood for participation in an atrocity.

Identity-based tensions are widely agreed upon as a risk factor for atrocities crimes.80 To target violence on the basis of a victim’s identity, negative attitudes and stereotypes must be constructed. Constructing these identities creates a division between an us and a them. Once a threat from another group is perceived, actions are taken to reduce that threat, up to and including participation in a mass atrocity. Without guarantees of security and a reduction in perceived threat, this security dilemma will perpetuate conflict.81 At the individual level, identity-based tensions manifest as prejudice, stereotypes, and a strong sense of Otherness toward an out-group.

Ideologies based on differentiation between identity groups can pose a risk of future atrocity crimes by generating exclusionary practices and policies that create a risk for mass violence or targeted atrocity crimes along ethnic, religious, or social lines.82 In the right circumstances, identity-based ideologies can become an “atrocity-justifying ideology.”83 Identity-based tensions and identity-based ideologies are of course closely related. Existing social tensions can fuel identity-based ideologies, but they can also develop separately.84 Limiting the individual support for identity-based ideologies is a long-term approach to preventing mass atrocities.

Impact on Risk

Analysis shows that atrocity risk remains stable even after participating in a reconciliation program (for statistical detail, see appendix 3). One explanation is that both test and control groups began with low levels of atrocity risk, which allowed limited space to observe change. In part, this reflects the exceptional nature of atrocity crimes, and raises significant challenges for the evaluation of atrocity prevention practice more broadly. Because atrocities occur so rarely, risk levels across the population will, on average, be low. Even at the country level, atrocity risk levels rarely exceed 5 percent.85 According to the Early Warning Project, which calculates levels for all countries in the world, the most at-risk country in 2015 ranked at only 13.2 percent. Most countries in the world fell far below that.

Low levels of risk may also reflect an inherent self-selection bias in voluntary reconciliation programs. A reconciliation program may not reach individuals with higher risk levels whose attitudes may have room to change. This issue is common to all reconciliation programs that rely on voluntary participation. Willing participation and the desire to reconcile are key to facilitating positive contact and meaningful encounters across identity groups. However, when opportunities for potentially transformative contact and dialogue are limited to ad hoc grassroots programs, then they run the risk of reaching only those whose attitudes already reflect the values promoted by reconciliation programming. Although the research design partially addressed this issue, it remains that low risk levels across all groups leave little space for a causal pathway into future atrocity prevention.

Another factor contributing to the stability is the slow pace at which attitudes and beliefs tend to change. A reconciliation program lasting only five weeks may not be long enough to dismantle deep-seated prejudices and divisive beliefs. Reconciliation is inherently nonlinear.86 Interpersonal reconciliation also depends at least in part on individual emotional capacity and well-being. Unpredictable personal factors such as trauma and emotional pain can influence the process of building more positive relationships between individuals. Navigating such a process may take far longer than five weeks. Other studies showing positive effects of reconciliation programs on attitudes toward trust, empathy, and intergroup relations have either more contact hours or a longer period of measurement.87

Short-term interventions, however, are a common reconciliation practice. Although most programs strive for longer-term engagement, they are constrained by funding, project cycles, and availability of participants. Programs are often limited to weekend-long intensive sessions or brief recurring meetings over a period of weeks. This study therefore raises questions about the utility of prevalent reconciliation programming and its theorized impact on the risk of future atrocities.

Structures to sustain positive connections and meaningful engagement across identity groups after the reconciliation programs end are also limited. Many participants return to homogenous communities and social circles and struggle to maintain the relationships built during the reconciliation program. Without sustained engagement, progress on attitude changes and challenging stereotypes may fade. This is particularly the case if negative attitudes toward the Other dominate in the communities and social circles they return to. For the deep attitude changes required for long-term atrocity prevention, short-term engagement around reconciliation issues may have limited effect.

Other Impacts

Although atrocity risk factors themselves remained largely stable after the end of the program, evidence suggests other positive impacts of the program that may contribute in the long term to reducing risk. Participants experienced positive contact that did, in some instances, challenge previously held assumptions about other identity groups. They also developed more inclusive senses of national identity, were more aware of reconciliation issues after the program ended, and demonstrated some evidence of increased empathy. These impacts did not extend to significant immediate changes in attitudes, but they are positive indicators for a reconciliation program.

The program provided opportunities for positive contact and the development of positive individual relationships between members of different ethnic groups. Program participants described new opportunities to speak to, befriend, and collaborate with members of different ethnic groups. Although few participants had no contact or friendship with people from other ethnic groups before the program, they still described a general feeling of distance and segregation in their everyday lives. Much of this dynamic can be attributed to language divisions between the ethnic groups, and the institutional structures built around the language divisions.

Despite the diverse student body at University of Colombo, academic life remains highly segregated. Language differences limit the ability for communication and impose a functional barrier to interethnic relationships. Coursework is offered in either Sinhala, Tamil, or English. That language correlates so closely with ethnicity effectively means that students have little opportunity to work with and get to know members of the other groups. One respondent described the dynamics of division between ethnic groups on campus:

And even our interactions in University, because [we have our classes in] Tamil, our opportunities for interaction are very limited. It is only in English class that we interact… [and that is just] one class. But in this group setting there […] was more opportunity for interaction.

A Muslim respondent described the often-unequal barriers that exist between majority and minority communities:

It [the reconciliation program] actually made us interact with the other communities. And we [Muslims] always get a chance to interact with the other communities, but the majority people [Sinhalese] get less chance to interact with us.

Because of the limited meaningful contact across language groups in their daily life, this program offered a rare opportunity to develop individualized relationships across majority-minority ethnic groups. Such relationships are a direct challenge to previous negative attitudes and stereotypes.

One Tamil respondent described how establishing a positive relationship at the individual level challenged previous negative attitudes toward Buddhist monks, who symbolize the religious practices of the Sinhalese majority:

I thought all monks were the same. But after the sessions I found out that not all monks are like that...There was a Buddhist monk in our group. I found out that even though you belong to the same ethnic group, there [are] individual differences between people.

By developing positive personal relationships, program participants were able to shift initial assumptions based on the individual’s social identity and connect on a basis of friendship and commonality. A Sinhalese respondent described it this way:

Earlier I thought of Muslims as a bit extremist. Even Tamils. For instance, though the LTTE lost the war, if Prabhakaran [former leader of the LTTE] won the Tamil people would have actually been happy…But when I met them [Tamils and Muslims] here I realized it’s not necessarily like that. They sometimes think exactly like us.

Bringing students of different ethnicities together for positive interpersonal experiences in an equal status environment seems to remove both language and social barriers that previously inhibited development of close interpersonal relationships across ethnic lines. It is hoped that, over time, through exposure to more positive interactions, positive stereotypes will replace negative ones and extend from the individual to the group level. It is unclear whether this presumed ripple effect of positive contact actually plays out over the long term. However, the short-term effects of this reconciliation program do indicate an individualized experience of positive contact.