Shaky Ground in Guinea

By Stephanie Schulze for ISN

On 3 December 2009, Guinea’s junta leader Captain Moussa Dadis Camara was shot in the head in an assassination attempt by one of his aides, Lieutenant Abubakar "Toumba" Diakite, and external pageflown to Morocco for medical treatmentcall_made.

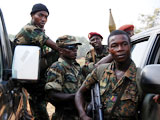

The event marked the peak of the political unrest that has plagued the country since Camara and his junta, the newly established National Council for Democracy and Development (CNDD), external pageseized powercall_made on 23 December 2008. The bloodless coup had come one day after the death of President Lansana Conte, who had ruled the country for 24 years with an iron fist and left the external pagemineral-rich country impoverishedcall_made.

Silencing the opposition

Camara had initially promised that neither he nor any junta member would run for president in the next elections. However, the external pagejunta reneged on that promisecall_made last August by announcing that any member of the CNDD was “free to put forward their candidacy for the national election.”

Protests intensified and culminated in a peaceful mass demonstration against military rule at the Conakry stadium on 28 September 2009, organized by the Forum des Forces Vives (FFV), a coalition of opposition parties and civil society organizations.

The event external pageturned into a tragedycall_made when members of the presidential guard sealed off the exits of the stadium where a crowd of 50,000 had gathered and started shooting, raping and killing people systematically. Human rights organizations spoke of at least 157 deaths and 1,200 people injured. Human Rights Watch (HRW) laterexternal pageissued a reportcall_made stating that the massacre had been premeditated by the CNDD to “silence opposition voices.”

It is assumed that the main reason behind the assassination attempt on Camara was a controversy over who initiated the killings on 28 September. His aide, Diakite, was head of the presidential guard, whose members carried out the atrocities.

The question of responsibility is likely to put junta members under pressure as the International Criminal Court (ICC) has started aexternal pagepreliminary investigationcall_made into the case.

Roadmap to democracy

Since the December assassination attempt, Camara has not returned to Guinea. He was external pageflown to Ouagadougoucall_made on 12 January, where mediation talks were being held under the auspices of Burkina Faso President Blaise Compaore. CNDD’s deputy General Sekouba Konate took over as interim head of state.

Under international and regional pressure, external pagean agreementcall_madedefining the steps for a transition to democratic rule was signed on 15 January by Camara, Konate and Compaore. It foresees the creation of a national transitional council “composed of 101 members representing all segments of Guinean society,” the appointment of a prime minister chosen by the FFV, and the organization of presidential elections within six months, which no member of the transitional government or military can contest.

Veteran opposition leader Jean-Marie Dore has been appointed prime minister of the transition government and the election date has been set for external page27 June 2010call_made.

While “the prospects of the transition are certainly better than they have ever been”, there is no guarantee that the elections will take place according to the agreement, Dr Gilles Yabi, a former senior political analyst for the International Crisis Group and expert on Guinea, told ISN Security Watch.

Keeping the military in check

The biggest hindrance to a peaceful transition is Guinea’s extremely divided, yet strong military. Having held on to power for so long, it is unlikely to concede it to civilian leaders easily. “Camara was representing the interests of most of the military chiefs and they will still do everything to remain in control, mainly for simple material reasons,” Yabi said.

The composition of the interim government is also a potential conflict factor. While the 39 ministers are balanced between the military junta, the opposition and the different regions, this also means that the prime minister will have no effective power, external pagesome saycall_made.

Furthermore, several ministers have been external pageimplicated in serious rights abusescall_made, including in connection with the massacre of 28 September – but instead of being held accountable, they now form part of the transitional government. Presidential Security Minister Lieutenant Claude Pivi is one of them. Like Camara, he comes from the Région Forestière and thus “may be watching carefully the decisions of Konate who is from the large Malinke group,” Yabi said.

In fact, external pageKonate has warned the military openlycall_madeto not undermine the transition to civilian rule, which shows how tangible that threat is. Yabi confirmed this, adding that Pivi had recruited thousands of young men in the army and militias by order of Camara. This might constrain Konate in his role of interim president and even threaten him “if he tends to neutralize Camara’s loyalists.”

Camara’s return to the country poses a external pageparticular threat to stabilitycall_madethat needs to be avoided; under the current plan, he is to remain in Burkina Faso as he recovers. Past experiences in West Africa have shown that holding fair and transparent elections is a tremendous task even under more facilitative preconditions. It is hard to believe that Guinea, which has no experience in organizing civilian elections, will accomplish this task in such a short amount of time.

In order for this frail stability not to turn into disaster, the international community needs to keep up both support of the transition plan and pressure on all those involved to adhere to it. It also needs to provide technical and financial assistance in organizing the elections.

But even if the presidential elections take place in June, Yabi warned that “in the mid and long-term, there is no guarantee that even good elections will not be followed by a new military coup or a lack of real control of the army by the new elected president.”

The efforts of the international community must thus go beyond the immediate success of the transition plan and focus on ways to strengthen the new civilian government in the long run in order to avoid new outbursts of violence in this war-ridden region.