Geopolitical Fault Lines – The Case of Afghanistan

5 Dec 2011

Is Afghanistan part of the Middle East, as our own in-house Digital Library classificationsystem suggests, or should we rather put it into South Asia or even Central Asia? Well, according to Afghanistan expert Kristian Berg Harpviken, director of the Peace Research Institute Oslo (PRIO), the answer is “none of the above.” As one of the obvious geopolitical fault lines in the world, the area known as Afghanistan has historically been in between all these regions. This uncomfortable status, however, does not mean that Afghanistan was isolated from them. In fact, the exact opposite is true. Afghanistan has been (and continues to be) an overt or proxy ‘playing ground’ for a variety of outside actors, both near and far.

Being a playing ground is not always a bad thing. Afghanistan’s status as a much intruded upon buffer zone between British India and the Russian Empire, as described by geographer external pageKeith McLachlancall_made, actually helped strengthen the area’s sense of itself as an independent nation. More recent foreign meddling, however, especially since the Soviet invasion in 1979, has yielded more familiar results – exacerbated ethnic and cultural tensions, rampant warlordism, drug trafficking, etc. In either case, what we see in Afghanistan is a classic geopolitical fault line where at present at least eight external actors are jostling for both influence and position in a 21st century version of the Great Game. Some of this jostling is overt, as in the case of Pakistan, and some of it is not, as in the case of the proxy war occurring between Saudi Arabia and Iran. These sometimes deadly skirmishes do not mean though that the Afghan people are the puppet-like playthings of fate. As McLachlan points out in “Afghanistan: The Geopolitics of a Buffer State,” and Harpviken more recently in “Afghanistan in a Neighborhood Perspective,” Afghan leaders do have varying degrees of leeway within the present circumstances. Despite the geopolitical weight of history on this area, geography is not ipso facto destiny.

A Classic Buffer State

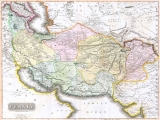

Keith McLachlan recalls that Afghanistan in its present form emerged in the 19th century. Both the British and Russian governments agreed that in order to avoid military confrontations in the area, they needed mutual strategic depth. The borders of this geographical safety valve were thus set along the Amu Darya River in the north and the so-called Durand Line in the south and east. (The Line, incidentally, has earned a well-deserved reputation as yet another example of clodhopper map drawing by geometrically-minded 19th century colonialists. That the border drawn proved to be almost totally indifferent to the tribal and ethnic distributions in the area is now the stuff of legend.)

[Resource Embedded:134680]

Regardless of the lines drawn, which maybe was the point after all, Afghanistan proved to be an ideal buffer between expanding empires. Landlocked and divided by the Hindu Kush (both in east-west and north-south directions), it also had a grossly undeveloped transportation network which neither British nor Afghan leaders wanted to develop. (The British neglected to build roads in order to prevent the Russians from easily moving southward, while Afghan leaders deliberately sought to use isolation as a way to maintain their independence.) This pattern continued well into the Cold War, despite competing American and Soviet attempts to build railroads and other forms of infrastructure. As McLachlan notes, an impoverished transportation system persisted for good political as well as economic reasons.”

But did the Afghan leaders of the time have no choice but to accept the geopolitical buffer role imposed on them? Not surprisingly, there is a division of opinion on this point. One school of thought has argued that Afghanistan was indeed at the mercy of two near-colliding empires while another has claimed that Afghan leaders deliberately chose isolation as a policy that served their communal interests best. In truth, the two arguments – foreign pressure and domestic will – do not necessarily contradict each other. What is clear though is that Afghanistan’s geopolitical role as a buffer zone seems to have served local interests relatively well, especially when compared to what was to come later. Indeed, in this regard McLachlan’s concluding words make much sense for the situation today: “[Afghanistan’s] strategic significance is as a negative zone where external powers intrigue but find it difficult to put down roots. In that sense, Afghanistan might have lost its dubious reputation as a buffer state in the context of the Anglo-Russian ‘great game’, but might now be caught in a form of stasis in which it still separates international communities rather than unites them” (p. 94).

An insulator caught between regional conflicts

McLachlan’s view contrasts with many contemporary optimists who have tried to, and persist in trying, to include Afghanistan into wider schemes of regional cooperation. These schemes include 1) making Afghanistan into an ’energy-bridge’ between energy-rich Central Asia and energy poor South Asia, 2) re-establishing its historical role as a focal point of regional transport and trade, and 3) politically linking its fate to a Greater Middle East, and thereby ending its geopolitical fault line status. As tempting as these schemes might appear, Kristian Harpviken does not share their optimist vision. He argues that Afghanistan is an archetypal “‘insulator’ caught between different regional state systems, each with a strong dynamics of their own”. To support his argument McLachan applies the regional security complex approach developed by Barry Buzan and Ole Wæver (see Regions and Powers: The Structure of International Security, 2003) to understand these dynamics in South Asia, the Persian Gulf and Central Asia.

Harpviken, in turn, acknowledges that with the dual Afghanistan-Pakistan strategy launched by U.S. President Obama in 2009, most policy-makers and analysts have come to recognize the importance of considering the regional multiple-moving-parts context in dealing with Afghanistan. Unfortunately, this new regional approach has yet to bear substantial fruits. Why is that? Well, Harpviken suspects that policy-makers have not used the right forms of analysis to inform their strategies. (In this context, PRIO has embarked on a four-part research project entitled “Afghanistan in a Neighbourhood Perspective”. Harpviken’s paper provides the foundation and will be supplemented by three studies of the regions depicted on the following map. “South Asia and Afghanistan” by Shahrbanou Tadjbakhsh has already been published; the two remaining papers on the Persian Gulf region and Central Asia are forthcoming.)

[Resource Embedded:134683]

When looking at regional security dynamics in South Asia, Harpviken writes, it is obvious that they are dominated by the conflict between India and Pakistan. The arguments are familiar enough – Pakistan fears strategic encirclement by India if the Afghan government leans too much towards New Delhi, while India is afraid of Pakistan using Afghanistan as a convenient strategic staging area and ‘backdoor’. In addition, there are several other major issues that remain unresolved, including the ultimate delineation of borders and the ultimate integration of the Pashtun people. In the latter case, Islamabad has long been afraid of losing its Pashtun territory, either to Afghanistan or to a new and independent Pashtun state. As a result of these problems, the courting of former Northern Alliance groups continues for India, as does its general economic penetration into Afghanistan. That these inroads fuel hostility and counter moves by Islamabad goes without saying.

In the case of the Persian Gulf region, its stake in the geopolitical future of the area in question is less clear. Prior to the 2003 Iraq War, a rough local balance of power dynamic existed between Iran, Iraq and Saudi Arabia. One of the major unanticipated consequences of the war was that this balance of power system broke down, thus leaving what is now a fierce, not-so-clandestine struggle for leadership in the Islamic world between Saudi-Arabia and Iran. What this has meant for Afghanistan is a low-grade proxy war within its borders. While Saudi-Arabia maintains close ties with Pakistan and has therefore also supported the Taliban, Iran’s antipathy towards these three foes runs deep. Interestingly, the dynamics in Afghanistan are such that the U.S. and Iran actually have overlapping strategic interests, to include minimizing the negative effects of the Opium trade. Unfortunately, these potential areas for cooperation have been overshadowed by U.S. and Western discomfiture over Iran’s nuclear program.

Finally, when compared to the two regions just briefly discussed, the security dynamics in Central Asia are likely to have the least detrimental effect on the situation in Afghanistan. Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan are the two countries which aspire to regional leadership, writes Harpviken, but their competition is likely to play out in their relations with Russia and China, and not so much in relation to Afghanistan. Nevertheless, Russia, which still regards Central Asia as part of its sphere of influence, remains wary of a U.S. presence not only in Afghanistan, but also in its former republics.

Yet China’s increasing presence within Afghanistan potentially distorts Harpviken’s arguments that the country is essentially a land-locked ‘insulator’ between South and Central Asian security dynamics. To fulfill growing demands for natural resources, China continues to invest heavily in the infrastructure and development of Afghanistan. In 2007, for example, the Jiangxi Copper Co. and Metallurgical Corp of China outbid Russian and American competitors to secure a $3.5 billion contract to develop the Anyak copper mine. Chinese companies are also participating in the construction of the Parwan irrigation project, as well as building railways and roads the length and breadth of Afghanistan. Such projects have given rise to speculation that China is attempting to revive the ancient Silk Road. Key to the redevelopment of this trade route will be the special economic zone in Wakhan Corridor, which connects Afghanistan with China’s Xinjiang province.

China also hopes that the redevelopment of the Wakhan Corridor will strengthen interconnectedness between Pakistan, Afghanistan, the Central Asian Republics and the Persian Gulf. One notable project currently under consideration is the construction of a railroad from Xinjiang travelling through Tajikistan and Afghanistan before terminating at the Pakistani port of Gwadar. Beijing’s $1.6 billion investment in the development of Gwadar Port potentially allows China to transport Middle Eastern energy applies across South and Central Asia. In time, the port may also allow China to project military power to safeguard its energy supplies.

In May 2011, Pakistan’s Defence Minister announced that Islamabad had requested that China also builds a naval base at Gwadar. While the naval base will ostensibly be for the Pakistani Navy, its location may allow the People’s Liberation Army Navy (PLAN) to expand its presence in the Indian Ocean and beyond. A Chinese naval base at Gwadar will undoubtedly alarm New Delhi that a traditional geopolitical rival has allowed another to increase its military presence so close India’s western coastline. India’s response may lead to a redoubling of efforts to increase its naval power, prompting geopolitical tensions akin to those developing in the Asia Pacific region.

Should this occur, Afghanistan may transcend its historical status as a landlocked geopolitical ‘buffer’ state and become part of an entirely different regional security dynamic. As an integral part of China’s energy network, Afghanistan will be intimately linked to the geopolitical ramifications of the PLAN’s stationing at Gwadar. In response, India may also redouble its efforts to expand its political and economic cooperation with Afghanistan. Consequently, Afghanistan may become the site of a distinctly Sino-Indian new ‘great game’.

Isolation rather than integration

Having broadly examined the three geopolitical security complexes bordering on Afghanistan, what preliminary conclusions might we draw from our analysis?

First, an obvious trend to watch out for, at least according to Harpviken, is a growing cross-regional alliance between Iran, India and Russia; it is dedicated to countering the Taliban, but not necessarily while supporting Western initiatives.

Second, the security discourse that surrounds South Asia, the Persian Gulf as well as Central Asia remains divided. There are those who argue it is too state-centric and traditional, but since regime survival remains a core feature of these areas, there are others who argue – with considerable validity – that such an approach is still appropriate.

Third, security relations in all three regions remain remarkably stable, meaning that regional enmities and loyalties endure. This signifies, at least to analysts such as Harpviken, that the influence of outside powers on politics in the region is actually rather limited. “For States in the region, one obvious response is to wait the interveners out”, writes Harpviken, which reinforces McLachlan’s parallel point about the area being a geopolitical “negative zone where external powers intrigue but find it difficult to put down roots.”

Finally, given that regional security dynamics in South Asia, the Persian Gulf and Central Asia play themselves out in Afghanistan regardless of Kabul’s wishes or inputs might not Afghan leaders make a unilateral guarantee of non-aggression? This would keep Afghanistan out of regional conflicts, or so Harpviken argues, and at the same time reduce its neighbors’ fear of Afghan militarization. The logic here, or so it seems, is that the security dynamics in neighboring regions are too complex and contradictory for Afghanistan to embed itself effectively in a regional forum or security network. What this implies is that Afghanistan’s geopolitical future might best be served by becoming a buffer state again. Such a policy, if supported by all its neighbors, would benefit the security needs of Afghanistan as well as those interested actors in neighboring regions.

Recommended Reading

Bodansky, Yossef (2010) Afganistan – Pakistan and Central Asia

Bropst, Peter John (2010) Afghanistan in the Balance

Chaturvedy, Rajeev Ranjan and David M. Malone (2009) India and Its South Asian Neighbors

Collins, Joseph J. (2011) Understanding War in Afghanistan

Harpviken, Kristian Berg (2010) Afghanistan in a Neighbourhood Perspective

Kaplan, Robert D. (2010) South Asia’s Geography of Conflict

Kjaernet, Heidi and Stina Torjesen (2008) Afghanistan and Regional Stability: A Risk Assessment

Lin, Christina (2011) China’s Silk Road Strategy in AfPak: The Shanghai Cooperation Organization

McLachlan, Keith (1997) Afghanistan: The geopolitics of a buffer state, Geopolitics and International Boundaries, 2:1, 82-96

Menkiszak, Marek (2011) Russia’s Afghan Problem: The Russian Federation and the Afghanistan Problem Since 2001

Sharma, Raghav (2009) India & Afghanistan

Tadjbakhsh, Shahrbanou (2011) South Asia and Afghanistan: The Robust India-Pakistan Rivalry

Kurečić, Petar (2011) The New Great Game: Rivalry of Geostrategies and Geoeconomies in Central Asia

In case you have missed any of our previous content on competing views of geopolitics, you can catch up here on: Geospatial Politics , Geopolitical Approach Number One - Current Justifications of Classical Geopolitics, Classical Geopolitics Today, Geopolitical Approach Number Two - Critical Geopoliticsand Critical Geopolitics - A Case Study, Geopolitical Approach Number Three – Geopolitics and the Rise of the Rest