The Six Historical Incarnations of the Modern State

2 Jan 2012

Our pre-Holiday Week discussion of Nationalism in a Globalizing World investigated, among other things, the evolving character of political identity and legitimacy in our changing world. In particular, we highlighted 1) the continued attempts by multiculturalists to diminish the role of nationalism as one of the primary ‘filters’ used in international affairs, and 2) the nativist political responses that these attempts have triggered throughout the European Union. This week, in our The State in a Globalizing World block, we will look at the state of the state – i.e., the evolving character of that formal political entity known as The State. But to know where The State is going, we first need to know where it has been. We need, in other words, to look at its history, as articulated in Phillip Bobbitt’s The Shield of Achilles: War, Peace and the Course of History.

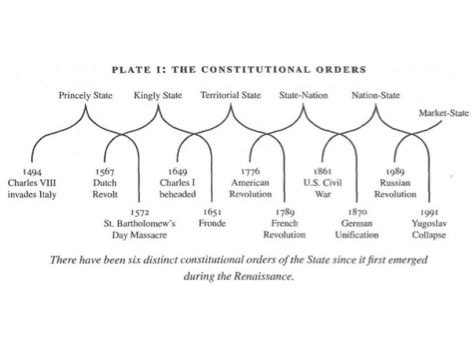

The five following plates from Bobbitt’s widely regarded tome illustrate the six historical phases he believes the modern State has undergone since roughly the 16th century. Each of these phases or incarnations reflected (and continues to reflect) a distinct ‘constitutional order’ – ranging from the Princely State of the Italian Renaissance down to today’s work-in-progress Market-State, which according to Bobbitt represents an entrepreneurial departure from the services-providing Nation-State which we are all familiar with. In Bobbitt’s view, however, the six distinct constitutional orders he identifies are not the mere creations of chance. As Plates II & III illustrate, they are the consequences of specific, society-shattering ‘epochal wars’, which led to peace treaties that were more templates than treaties – i.e., templates for new forms of state-based international order. The states within each order then used the innovations that defined each era (Plate V) to help legitimize their own standing (Plate IV) and ensure their own longevity.

Ultimately, what the Shield of Achilles argues is that the modern state came into being for two fundamental reasons – “to establish a monopoly on domestic violence, which is a necessary condition for law, and to protect its jurisdiction from foreign violence, which is the basis for strategy.” In other words, the internal posture of a state towards its citizens and its external posture towards other states are “two sides of one ‘membrane.’” This argument, which Bobbitt unfolds over nine-hundred pages, is much more vast and intricate than we’ve recapitulated here, but its basic logic is straightforward enough – strategic imperatives drive constitutional innovations, which create new strategic imperatives. In response, various new models of constitutional order emerge and compete with each other, with the competition eventually erupting into era-defining ‘epochal wars’. These epochal wars, in turn, are won by states whose constitutional orders are best adapted to the strategic realities of their time and therefore result in war-ending settlements that install the victorious constitutional order as the new benchmark for legitimacy within a new international order. This, for Bobbitt, is the essential logic of the modern state’s historical development.

Significantly for us, this logic is still in place today. The 20th century for Bobbitt was largely a Long War (1914 – 1991) between three competing models of the nation-state - communism, fascism and parliamentarianism. With the final victory of the latter, the parliamentary version of the nation-state has been installed as the gold standard for international legitimacy. But history did not end here, as Francis Fukuyama tried to imagine. The basic logic of The Shield of Achilles does indeed continue apace. For example, some of the very military-strategic advances that won the Long War (nuclear weapons, rapid computation and international communication) are now helping throw the nation-state into crisis, to include encouraging the emergence of a competing model of constitutional order – the market-state. Whereas the legitimacy of the nation-state was (and remains) based on the assorted forms of welfare the state manages to secure for the nation and its people, the legitimacy of the market-state is based on the opportunities it provides for individuals, as entrepreneurs of their own lives, to fulfil their greatest potential as human beings. Fair enough, but does the market-state represent the sixth incarnation of the state in general, as Bobbitt would have us believe? What about the Chinese model of ‘authoritarian capitalism’ – does it merely hearken back to a 20th century past or does it actually point to a more complicated future than Bobbitt allows? If history is any guide, another epochal war might be needed to settle the matter of which constitutional order will be the most ‘legitimate’ one among several.

To investigate Philip Bobbitt’s arguments in more detail than we could ever do here, these classic interviews, courtesy of the University of California Berkeley’s Conversations with History Program, are a good place to start:

[Resource Embedded:135599] [Resource Embedded:135600]

For the rest of our content on "The State in a Globalizing World," check out our dossier on the topic.