Watching Over You

22 Feb 2012

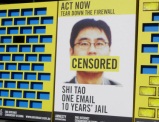

Yesterday we kludged together Gene Sharp’s philosophyof nonviolent resistance with Clay Shirky’s external pagebeliefcall_made that social media is a revolutionary instrument of political change. Our intention was indeed to celebrate the potential empowerment this media can provide the average person in the street. But as we also mentioned yesterday, every positive has its negative. In the case of Sharp and Shirky, it is Evgeny Morozov’s beliefthat internet-based media can be used, and indeed is used, by repressive regimes to maintain their grip on power. (They do so by gathering open source intelligence, co-opting bloggers, planting legitimacy-enhancing narratives, etc.) China is perhaps the most celebrated example of a state today that actively seeks to limit its citizens’ access to the internet. It is about to invoke a external pagenew lawcall_made, for example, that will require users of Sina Weibo, China’s most popular micro-blogging site, to register under their real names.

And yet, although it is easy to point an accusatory finger at repressive regimes, today’s presentation confirms that states with bona fide democratic credentials are just as guilty of internet censorship as the ‘usual suspects’. Our first map, for example, is based on data provided by external pageReporters Without Borderscall_made (RSF) and identifies those states which external pageengage in overt cyber-censorshipcall_made. As so-called “Internet Enemies” the countries marked in red make up a familiar ‘who’s who’ of online censors – Myanmar, China, Iran, etc. Cyber-attacks to silence dissenting opinion, slowing down bandwidth during elections or simply cutting off access altogether are among the common tools of their trade.

When we turn, however, to RSF’s list of “Countries under Surveillance,” marked in yellow on the map, it is by no means made up of rogue or failed states and repressive regimes. Instead, it includes democratic nations such as Australia and France, which RSF accuses of subjecting their ‘netizens’ to targeted filtering and severely limiting their online freedom of speech. Additionally, RSF deems assorted “Countries under Surveillance” to be guilty of intimidating online journalists and bloggers with threats of violence and/or legal proceedings.

[Resource Embedded:136198]

Ultimately, the main difference between RSF’s “Internet Enemies” and “Countries under Surveillance” is outlined by our second map. While the number of imprisoned netizens seems comparatively small, the map nevertheless reflects several defining features of the current international system. That China leads the way in terms of punishment of its netizens is a given. Whether the number of such imprisonments will rise as a result of previously mentioned legislation is yet to be determined, as is the case of the Middle East in the wake of the Arab Spring. Yet, if we focus firmly on the here-and-now, there is one undeniable ‘truth’ to glean about censorship and the internet: if states are suitably motivated to restrict their netizens’ access online, then there is little the international community can do in the short-term to prevent them.

[Resource Embedded:136197]

Suggested Reading

Internet Freedom: A Foreign Policy Imperative in the Digital Age

This article echoes this week’s theme – new communications technologies represent both a medium for individuals to broadcast their ideas freely around the world, and a tool that empowers authoritarian governments. In either case, the internet has emerged as a major force in international affairs – a force that will have lasting implications for the international community.

Weibo and "Iron Curtain 2.0" in China

This piece analyzes the political impact of the internet on Chinese state-society relations. In particular, it examines how government censors try to manipulate the use of the internet and Weibo (the Chinese version of Twitter), while the latter’s users gamely try to gather information, exchange views, and organize protests against the government.

Internet in Iran: More Freedom in the Country?

Consistently ranked on the list of countries deemed "enemies of the internet,” Iran is one of the most dangerous places to be a blogger, given the extreme restrictions placed on online activities. The restrictions include draconian legislation, infrastructure limitations and garden variety arrests.

Democracy Promotion in the Age of Social Media: Risks and Opportunities

The prominent role played by social digital media in the popular uprisings across North Africa and the Middle East led to the dubious catchphrase “Social Media Revolution”. Critics of such nomenclature argue that Western policy-makers risk being hamstrung by any cyber-utopian views that suggest the internet is inherently pro-democratic.

external pageOpenNet's Access Seriescall_made

The Access series includes three edited volumes, published by the OpenNet Initiative and MIT Press, which document nearly a decade’s worth of technical and in-field research on the trends and patterns shaping information controls around the world.

external pageWho Controls the Internet: Illusions of a Borderless Worldcall_made

This 2006 book by Jack Goldsmith and Tim Wu assesses struggles to control the internet. The authors argue that the net’s destiny will inevitably reflect the interests of powerful states, and while it may help change some of the ways that states govern, it will not diminish the most fundamental roles of government any time soon.

external pageAuthoritarian Informationalism: China's Approach to Internet Sovereigntycall_made

In light of the Google-China conflict, this article discusses the issue of internet sovereignty and, in particular, focuses on the various claims the Chinese government makes in order to assert its authority over this domain. This form of state sovereignty will continue to reflect an internet development and regulatory model – ‘authoritarian informationalism’ – that combines elements of capitalism, authoritarianism, and Confucianism.