Power as Truth – Unmasking the Relationship

5 Apr 2012

Starting in the mid-19th century, traditional theories and characterizations of power came under increasing attack by more critical approaches. The unifying thread behind most of these counter-theories of power turns on where power comes from. In the case of neo-Marxists (see yesterday’s discussion), power derives from material and social structures rather than from actors. These structural forms of power then create different social arrangements which additionally produce different kinds of actors who exercise different forms of economic and cultural hegemony. Now this critique of power as a form of physical and mental control remains a powerful one, but it is not the only one. Post-structuralist critiques of power, for example, are also germane here. They place power everywhere and firmly at the grassroots level.

Like Marxists, post-structuralists do not treat political actors as ‘black boxes’ or externally observed billiard balls careening off each other. Instead, they attempt to “get inside” political actors by highlighting how they are the products of their social circumstances. But in sharp contrast to Marxist views, post-structural interpretations of power focus on how individuals are the products of decentralized, diffuse, and unstable social structures – i.e., structures such as language, systems of knowledge and categorization, etc. Just as actors are empowered (to different degrees, of course) by their institutions and material conditions (as Marxist analyses emphasize), they also derive power through language and from the social meaning of basic categories such as what is ‘natural’ or ‘normal,’ or what counts as ‘true’ or ‘false.’ Because categories such as these ultimately shape what it means to be a political actor in the first place, the linguistic and other social practices from which they arise are a profound source of power, or so the post-structuralist argument goes. But notice though that while this view emphasizes power’s domination over the individual, it simultaneously emphasizes the power that resides in individuals. In other words, power structures are indeed everywhere, but they operate only as a result of our interaction with them.

Productive power

Michel Foucault used the term “productive power” to refer to the ability of language and discourse to produce subjects with different social identities and characteristics. The classic example of a subject produced by power, according to Foucault, is the modern prisoner “whose marginalized identity is constructed through the disciplinary and normalizing techniques of power.” In pre-modern times, Foucault goes on to argue, the goal of punishing individuals for crimes was to exact revenge on behalf of society. By contrast, the goal of much of modern punishment is no longer simply revenge but the ‘rehabilitation’ or ‘normalization’ of criminals. One of the effects of this movement towards rehabilitation is a change in the social definition of what it means to be a prisoner – i.e., to defining the prisoner as a deviant social subject with radically limited social capacities. Indeed, this conception of the prisoner as marginal and abnormal, which we take for granted today, is actually a recent invention, like all of our social identities and categories. In addition to imposing power over the prisoner by forcibly confining him to a cell, power in modern disciplinary systems further defines, in highly negative terms, who or what he is.

In contemporary international politics, Foucault’s productive power can also be discerned in the life or death power of categories such as ‘civilian’ and ‘combatant’ in international humanitarian law, and in labels often applied to states – i.e., ‘Western,’ ‘rogue,’ ‘authoritarian,’ ‘post-colonial,’ ‘failed’ or ‘failing,’ etc. Such terms, a post-structuralist would argue, are not merely descriptive. They determine, through the linguistic power they possess, what a labeled state can and cannot do in the international system.

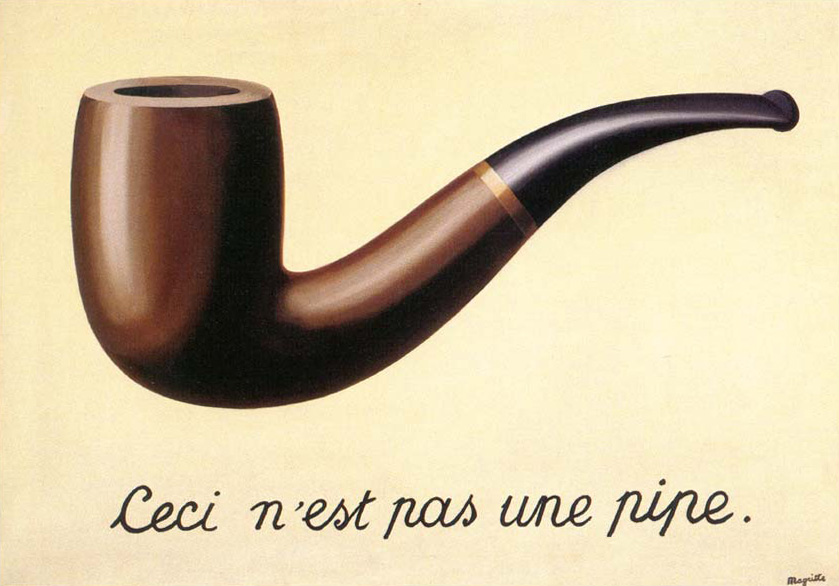

Because power operates through language, or so Foucault argues further, it operates at the level of the individual. This means that power is everywhere and that everyone is constantly exercising it all the time, whether they realize it or not. In many cases, therefore, the ideas we express and the language we use are exercises in power. We express ourselves not necessarily to communicate, but actually to dominate. Key to the rehabilitation or normalization of prisoners, for example, is our requirement that they self-identify as prisoners. Indeed the modern prison, according to Foucault, is the model for all modern systems of disciplinary control which “combine into a unified whole the deployment of force and the establishment of truth.” If we cut through this prose, we are left with a clear post-structural view of power. Political systems are also systems of disciplinary control. They exercise this control by establishing ‘truth.’ This ‘truth’ is therefore “deeply implicated in power.” Rather than understanding power as “distorting, concealing, or repressing truth,” power now operates “through truth itself,” and we are complicit in it.

One of the main consequences of the explicit identification of power with knowledge and truth is the rejection of a privileged, objective position outside of power. Consequently, one of the central claims of post-structuralist analyses of international politics is that “international relations is a discursive process of knowledge as power.” If truth is so deeply implicated in power, any attempt to make sense of the world is ultimately also an act of power. Rather than produce a more accurate or ethically sound ‘truth’, then, the politically responsible person should focus on bringing the operation of power to light – not to oppose power, but to use it and show how it works. The goal, in other words, should thus be to unmask "the will to power masquerading as the will to truth.”

Power/Knowledge in the China-Taiwan relationship

Among post-structuralism’s recurring features is its sensitivity to “discursive closure” – i.e., to instances where “attempts are made to bring ambiguity under control, where a privileged interpretation emerges, or where conduct is disciplined and discourse limited.” This kind of closure, it turns out, is one of the tell-tale signs that the dead hand of productive power is at work.

To illustrate this point, let’s consider a post-structuralist perspective on the relationship between China and Taiwan. Standard accounts of the relationship are full of examples of “discursive closure.” Analyses prevalent in the foreign policy establishments of Washington and Beijing, for example, focus on the role of Taiwan in the regional military balance between the United States and China. These practices (according to Rosemary Shinko) tend to represent the US and China as two ‘titanic foes … squaring off in a primordial contest between good and evil.” Framing the situation in this way, she argues, privileges a certain view of the conflict and undermines others. Indeed, “such a dichotomous representational frame oversimplifies myriad complexities and also encourages political practices which necessarily categorizes actions, words and thoughts as either/or,” thereby limiting other views. Ultimately, this “scripts a scenario whereby cross-strait relations become denotated as one of the most dangerous sites in global politics” where it sometimes seems that “inexorable forces are at work.”

One major effect of this ‘script’ in Taiwan is that public discourse on “security” and “welfare” is confined almost exclusively to the preservation of the Taiwanese state and “Taiwanese” cultural identity vis-à-vis mainland China. For Shinko, this is a clear case of productive power at work. According to Shinko, we can become more aware of it by paying attention to “marginal sites of resistance and transgression” against established categories and ‘truths.’ One such site is the struggle of the indigenous people of Taiwan for recognition and cultural survival. According to Shinko, it is here “that the power deployed [by mainland transplants] to construct an overarching, unified, national, Taiwanese identity becomes visible.” Thus, the marginalization of the indigenous Taiwanese – who would tell quite a different story about the meaning of ‘security,’ ‘welfare’ and ‘what it means to be Taiwanese’ – brings to light how ‘truths’ (and therefore power) can emerge and become fixed by linguistic and other social circumstances. It reveals that “Taiwanese national identity” (as most commonly understood) is neither natural, nor inevitable, but (discursively) produced – and that this has real consequences for the circumstances and fates of the indigenous Taiwanese. Indeed, this too is a form power, post-structuralist style: power which dominates all of us but which also ultimately resides in the words and ideas of each of us.