Canada's Troubled Legacy

26 Apr 2012

By Josephine de Whytell for ISN

“Our object is to continue until there is not a single Indian in Canada that has not been absorbed into the body politic, and there is no Indian question, and no Indian department” – so said Duncan Campbell Scott, a Deputy Superintendent in Canada’s Indian Affairs department in 1920.

When the British Crown negotiated numbered treaties with the native populations of Canada in the nineteenth century, they recognized their existence as different peoples having control and sovereignty over different areas of land across Canada. As the European Union comprises a patchwork of sovereign countries, so too did Canada; the lack of recognizable formalized boundaries and written legal instruments of the sort relied upon in Europe, however, created space for the colonial settlers to craft their own territories and consume the vast landscape with certified rights in the form of land titles. As colonialism spread throughout the country, the Indigenous peoples who had agreed to share their land became segregated, ostracized and punished for trying to maintain their way of life.

Targeting the next generation

Article 2 of the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide defines “genocide” as including the act of forcibly transferring children of any national, ethnic, racial or religious group to another group with the intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnic, racial or religious group. Canada opened its first ‘Indian Residential School’ in British Columbia in 1840 with the last school of this type only closed in 1996. During the 156 years that these schools existed, indigenous children were forcibly removed from their parents’ homes and communities and placed in these church-operated boarding schools set up to ‘kill the Indian in the Child’. They had grown up surrounded by their own unique languages and traditions but were now confronted by an alien value system designed to mold them into ‘Canadian’ citizens.

Indigenous law is taught through observation and the sharing of stories that inspire and provoke intrinsic morality and the growth of conscience, as opposed to having a written set of rules and laws that are enforced against people. The Eurocentric notion of law being forceful, binding and punishable is considered unnatural and counter to Indigenous knowledge and values; as a result, its imposition upon Indigenous peoples had limited value or meaning. When children entered the residential schools they were confronted with a system of rules that was entirely new to them; their long braids were cut, their traditional clothes destroyed, their languages banished and -- whether they understood the English commands being given to them or not -- they were physically punished for any wrongdoing.

In addition to the physical assaults, children were taught that everything about their culture was wrong: They were inferior people and should aspire to be like the European settlers. When children left these schools, having been emotionally, physically and too often sexually abused, they only had limited knowledge of their traditional ways and were forced to join a society that held nothing but disdain for them. Either because of the schooling including lengthy periods of manual labor as opposed to education, or because of the effect of the abuse on the students’ ability to concentrate, many children leaving Residential Schools had only a limited education, often only being able to secure employment in (low-paid) manual laboring positions. Due to the inhumane treatment they received, many youths also began using alcohol or other substances to ease the pain they felt and dampen their feelings of inferiority, self-loathing and lack of self-esteem that accompanied their abuse.

A new generation was born whose parents were, to a large extent, broken: disjointed from their culture and their family, unable to love or be loved, lacking in self-confidence, lacking in the intrinsic Indigenous morality that their ancestors had cherished -- and forced into a new system of laws that they hadn’t prescribed to, but found themselves imprisoned by. The Indian Act changed their internal systems of government to mirror the Eurocentric, chauvinistic and privileged model. Where Indigenous ways had promoted equality, peaceful negotiation and harmony, the Canadian government imposed class prejudice which bred corruption and dragged Indigenous ways into the adversarial forum of law as a battlefield, rather than a roundtable. Implant into this contorted system of government the victims and survivors of residential schools and today’s income gap, over-representation in prisons, over-representation in foster care, under-education and general malaise is inevitable.

Canada’s third world

While Aboriginal – defined as First Nation, Inuit, and Métis -- people of Canada make up approximately 5% of the total population of Canada, they accounted for 17% of the federal prison population in 2005, when the last census was conducted. In provinces such as Saskatchewan, 79% of the external pageprison populationcall_made is Aboriginal, despite only accounting for 15% of Saskatchewan’s population. Throughout Canada, 30-40% of the external pagechildren in carecall_made are Indigenous. 32% of Aboriginal Canadians do not have their secondary school diploma, compared with 15% of non-Aboriginal Canadians; only 8% of Aboriginal peoples in Canada have a external pageBachelor’s degreecall_made compared with 22% of non-Aboriginal Canadians. In 2006, the average non-Aboriginal income was nearly $10,000 higher than the average Aboriginal income. In October 2011, the Attawapiskat First Nation declared a external pagestate of emergencycall_made due to having no electricity, no running water, no sewage facilities, inadequate and substandard housing, and a health and safety crisis that was ensuing.

Canada’s third world is a reality for many indigenous Canadians, who find themselves impoverished, homeless, imprisoned, and victims of institutional and systemic discrimination. The external pageAssembly of First Nationscall_made, the external pageNative Women’s Association of Canadacall_made, and the First Nations Child and Family Caring Society are but a few of the organizations that have identified the continuing inadequacies of Canadian law and politics to deal with the disparity, and yet the situation remains. Approximately 8,000 children are in the care of external pageFirst Nation Child and Family Services Agenciescall_made, which contributes to a total of 27,000 children in First Nation and Provincial Social Services agency care - external pagethree timescall_made the number of children that were in Residential Schools at the height of their operation.

Building bridges? Poorly, if at all

The Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada (TRC) was established by an historic settlement agreement between Canada, the Church entities who had operated the Residential Schools and Aboriginal organizations. There was also an Agreement which set up an extensive adjudicative processes for compensation to be delivered to Residential School survivors. The TRC has the difficult task of attempting to heal the deep wounds of colonialism and aiding reconciliation -- and there is hope amongst many of Canada’s Indigenous peoples that this gesture will be able to have some meaning. So far, however, Indigenous peoples are the only ones at the table. Canada is being taken to Court for its non-compliance with the Indian Residential Schools Settlement Agreement, specifically with respect to its external pagedocument production obligationscall_made.

It is obvious that the legacy of Canada’s policy of assimilation lives on through the hearts, minds, and processes of government and many of the citizens of Canada. The Ministry of Social Services may have closed Residential Schools but they also instigated the widespread adoption of Aboriginal children into non-Aboriginal homes, a practice that continues today. Although the legislative tools are available to assert that ‘culture ought to be protected’, the people whose opinions count in matters of implementing government policy remain convinced that what’s best for Aboriginal people is if they live, act, speak, and think like non-Aboriginal Canadians.

The lack of understanding and value that is attributed to Aboriginal cultures, traditions, knowledge, and languages in Canada is a breeding ground for racial hatred and intolerance. This flies in the face of Canada’s international reputation for pursuing equality and peace-keeping within the United Nations forum. Instead, Canada’s institutions perpetuate and indirectly promote discrimination towards Indigenous peoples in Canada despite the forward-moving jurisprudence and academic alliances with cultural equality. The reasons for this are the remnants of colonial superiority ingrained deep into the Canadian psyche.

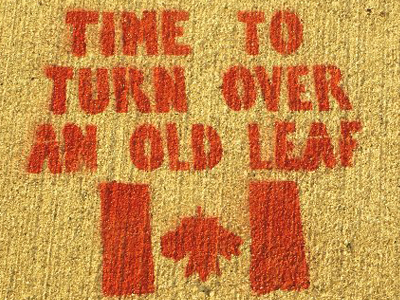

National Chief Shawn Atleo of the Assembly of First Nations noted in his external pagespeechcall_made to the Calgary Chamber of Commerce in March 2012 that, “[w]hile Canada consistently ranks within the top five on the UN indexes, First Nations are well below ranking among developing and third world nations.” Canada may appear to be a first world country and play a key role in promoting equality and peace-building activities internationally, yet it seems to have turned a blind eye to the poverty and the conflict of its own making.