A Post-American Hemisphere?

1 May 2012

Most experts agree with Eduardo Galeano – over time, foreign influence has had a deleterious effect over South America. In the 17th and 18th centuries, this meant direct European colonization and control. After the 19th century surge towards independence, foreign influence became more financial and economic than political, and eventually more American than European, as the “Colossus of the North” spread its hegemonic shadow over the hemisphere. Indeed, external pageas Barry Buzan and Ole Waever arguecall_made, the United States was for all intents and purposes the only major external player in South America in the 20th century.

In recent years, however, American influence has waned in this part of the world. South American countries are increasingly looking for social, political and economic solutions among themselves, either by 1) forming their own regional organizations that minimize or exclude the US, or 2) seeking friends and opportunities outside of Washington's orbit. These attempts inevitably raise obvious questions. Is the southern half of the Western Hemisphere entering a genuinely post-American period or not? Are other rising powers, such as China, effectively establishing their influence, and if so to what ends? And finally, will local actors be able to shape the future of the region, to include quarantining foreign influences effectively?

A South American Union?

Locally-driven pro-integration efforts have made considerable progress in South America. The first of these was the Andean Community, established in 1969, which today unites the 100 million inhabitants of Bolivia, Colombia, Ecuador and Peru into a regional customs union.

In 2006, Venezuela withdrew from this community in order to sign a membership agreement with Mercosur, the Southern Common Market, which is the southern counterpart of the Andean Community. At present it consists of Argentina, Brazil, Paraguay and Uruguay, although Chile and the countries of the Andean Community are associate members and Venezuela is in the final stages of being ratified as a full member.

The Union of South American Nations (UNASUR) represents the next logical step beyond the Andean Community and Mercosur. Its aim is to combine its predecessors into a locally adapted version of the European Union. In addition to merging the two customs unions, UNASUR aims to permit the free movement of people, eliminate tariffs, promote economic development, and create a common defense policy for all South American countries. According to its constitutive treaty signed in 2008, the Union’s headquarters will eventually be in Quito, Ecuador, its parliament in Cochabamba, Bolivia, and its central bank in Caracas, Venezuela. With the treaty coming into effect in March 2011, the general consensus is that UNASUR represents, at least conceptually, a bold next-step departure from the standard South American narrative of foreign exploitation and under-achievement.

Or a Changing of the Guard?

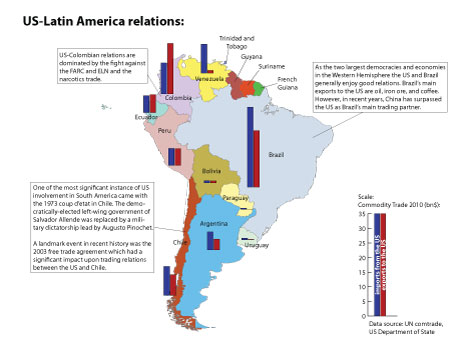

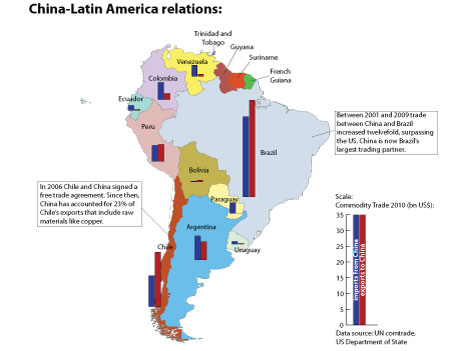

As promising as the above examples of political integration are, particularly UNASUR, analysts are not necessarily wrong to ask if they are symptoms of “build it and they will come.” Superstructural change is one thing, but what about the seemingly hardwired inequalities that still plague the region? Is South America inexorably moving away from the old narrative of negative foreign influence or is it merely assuming a new guise? Measured in terms of volume of trade, for example, China is now at least as important to South America as the United States (see the graphics below). Is that statistical truth a neutral one or does it bode ill, yet again, for the region? Well, maybe not yet.

As the graphics below illustrate, the US grip remains tight on the northern countries of Ecuador, Colombia and Venezuela. But in Brazil (the region’s largest economy) and Chile (despite a recent free trade agreement with the US), China is now the most important trading partner. What the data might be telling us, therefore, is that the picture here is a mottled one. Old influences linger, new ones are taking hold and local forces continue to struggle for enhanced autonomy and power. As a result, what this mix will ultimately yield remains an open question.

Click on the links under the images for larger versions: