The World’s Not-So-Hidden Criminal Economy

10 Sep 2012

While globalization has facilitated the flows of funds, people and communications across borders, it has also provided the opportunity for the illicit exchanges of goods, capital and even human beings. Indeed, such exchanges add substance to those who have long claimed that national and international security should be writ large – i.e., that we should view transnational crime as a major symptom of the “threat proliferation” we now confront at the individual and state levels. An obvious reason for this “horizontal” growth is the explosive rise of information and communications technologies (ICT) we have seen over the last 25 years. The revolution in ICT has permitted the networking of previously isolated activities to an unprecedented degree, and networking can obviously be used for good and ill. In the case of transnational criminal organizations, the capacity to network dynamically has provided them with the opportunity to both hide and diversify their illicit trade. And as organized criminal networks make increasing inroads into legitimate commercial activities, they provide the opportunity to not only study their impact on the not-so-hidden “black” global economy, but to a lesser degree the overt one as well.

In the following video, the Council on Foreign Relations’ external pageStewart Patrickcall_madeand the University of Pittsburgh’s external pagePhil Williamscall_made summarize the rapid global expansion of transnational organized crime. Williams begins by explaining why the money-raising activities of global criminal networks have benefited from the changes commonly ascribed to globalization, to include the deregulation of international finance from the 1970s onwards. Our speakers then go on to talk about the different types of criminal organizations and networks that have emerged as a by-product of the globalization process, as well as the diversified challenges they pose to both national and international security.

external pagecall_made

Global, Profitable and Diverse

In the wake of the above presentation and the information it provides, it should surprise no one that it is difficult to determine the true costs of transnational organized crime on the world’s economy. (Again, the ability of these organizations to hide their activities within cross-border and relatively horizontal networks is part of the problem.) The United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC), for example, external pageestimatescall_made that criminal gains amount, on average, to 3.6 per cent of global Gross Domestic Product (GDP). Moreover, if only ‘typical’ transnational criminal activities are taken into account (human trafficking, counterfeiting, narcotics, to name but a few), the UNODOC estimates that such activity would still account for a noteworthy 1.5% of global GDP.

Of particular concern in the blending of legitimate and illegitimate economic activity is the laundering of “dirty money,” which is estimated to account for between 2 – 5% of global GDP in any given year, and which remains a particularly severe problem in developing countries. Indeed, research covering a recent five year period suggests that money laundering activities throughout the developing world accounted for approximately 50 per cent of all illicit financial flows. To put it another way, these transfers represented 7.3 per cent of the developing world’s GDP, which is 3 times greater than the GDP-equivalent flows originating from industrialized countries.

Again, the above numbers not only represent the sheer volume of criminal financial activity, they also illustrate its growing diversification. Investigators have suggested that there are at least external pagefifty business sectorscall_made where criminal networks are thought to have obvious commercial interests. The following chart partially illustrates the extent of these interests and just how lucrative they are.

Product/Services

Value in U.S. Dollars

Counterfeit Drugs

$200 billion

Counterfeit Electronics

$169 billion

Software Piracy

$58.8 billion

Gas and Oil Smuggling

$53.64 Billion

Human Trafficking

$32 Billion

Waste Dumping

$11 Billion

Counterfeit Aircraft Parts

$2 Billion

Counterfeit Weapons

$1.8 Billion

Arms Trafficking

$1 Billion

Nuclear Smuggling

$0.1 Billion

Source: Havoscope Black Markets, external pagewww.havoscope.comcall_made

There is always a Place for Trafficking

The above statistics further suggest that the interests of criminal syndicates are not random; instead, they are specifically targeted. They primarily focus on the most popular or essential commercial products available. Yet, while the ‘business’ of arms trafficking appears to be far less profitable than counterfeiting or “redistributing” consumer products, our previous week’s focus on arms trafficking and security confirms that criminal networks do “dip their toes” into this area and will continue to do so well into the future. International organizations have external pagepreviously estimatedcall_made, for example, that there are 20 million illegal firearms circulating in Mexico alone. No one disputes that the vast majority of them can be traced back to criminal syndicates in the United States, but lesser syndicates in other parts of the Americas play a role too.

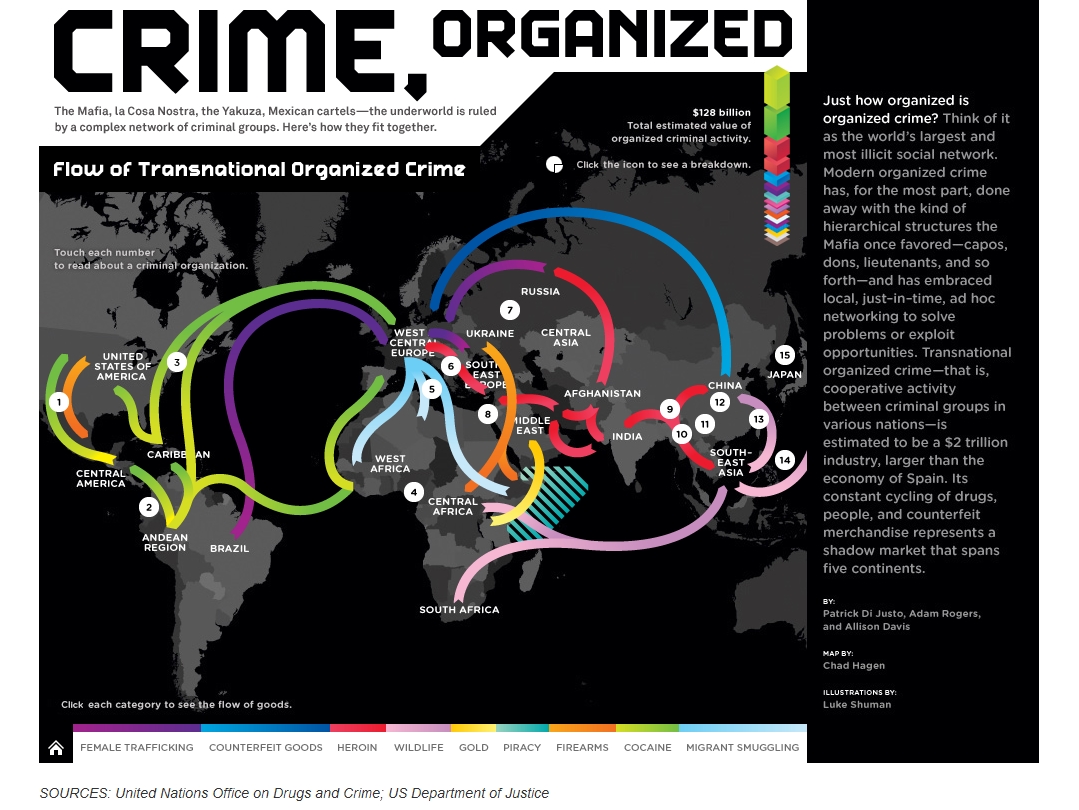

The flow of illegal firearms into Mexico is not only eyebrow-raising but also illustrative. In other words, it confirms that the supply routes used by criminal networks are not only multinational but also highly flexible. The following infographic from Wired.com depicts some of the major transit routes used by transnational and networked groups. It shows that few (if any) illicit activities are confined to a particular transit route. Diversification, after all, permits criminal networks to bypass the international system’s attempts to curb the trafficking of illicit products and services.

A Constant Challenge

To quickly summarize, it is obvious that transnationally networked organized crime is not only here to stay, it also represents a security problem writ large. Money laundering, for example, undermines a state’s ability to safeguard the health and wellbeing of its citizens. Lucrative drugs businesses often nest in the most impoverished sections of society and then corrode that society from within. Mere “shadow states” are often the result. Efforts to deal with these problems have had some success, but the cross-bordered and networked natures of today’s criminal organizations have complicated coordinated regional and international efforts to counter their cancerous growth, as we will see throughout this week.

Further information on the challenges posed by transnational organized crime can be accessed from the following materials:

- United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC): external pageOrganized Crimecall_made

- CFR International Institutions and Global Governance Program: external pageCrimecall_made

- International Peace Institute: Spotting the Spoilers: A Guide to Analyzing Organized Crime in Fragile States

- TED Talks: external pageMisha Glenny investigates global crime networkscall_made

- World Economic Forum report: external pageOrganized Crime Enablerscall_made