Food Security by Numbers

1 Oct 2012

The World Health Organization (WHO) defines external pagefood securitycall_made as a situation where “all people at all times have access to sufficient, safe, nutritious food to maintain a healthy and active life.” Conversely, the United Nations’ (UN) Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) explains that external pagefood insecuritycall_made may be caused by a number of factors, including the unavailability of food, inadequate purchasing power, or “inappropriate utilization at [the] household level.” Forms of food insecurity include undernutrition, which results from “prolonged low levels of food intake” and/or “low absorption of food consumed”; undernourishment, where food intake regularly provides less than minimum energy requirements; and malnutrition, which is caused by “inadequate or unbalanced” food intake.

A ‘Developing’ Problem

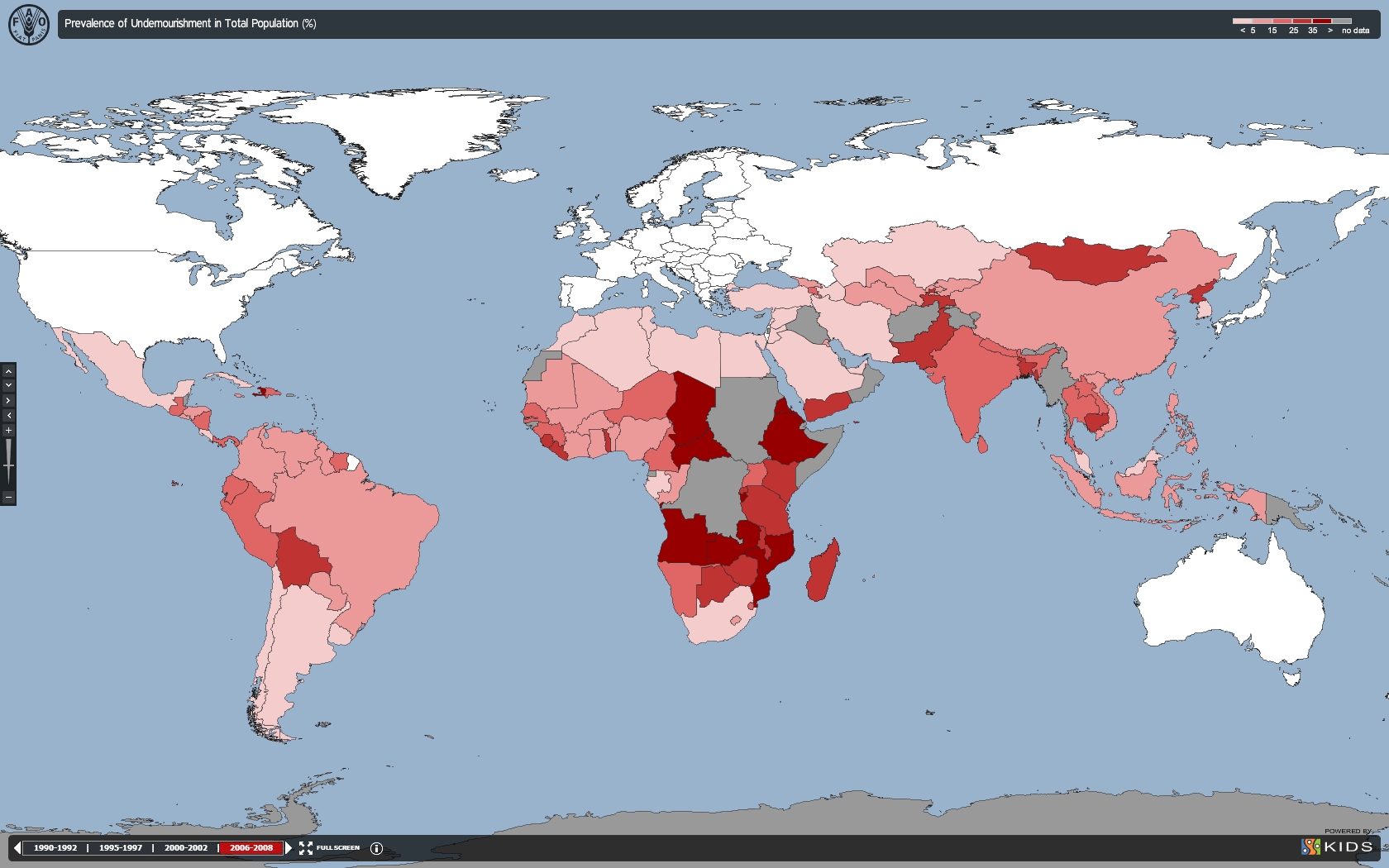

external pageAccording to the FAOcall_made , 850 million people - or 13% of the world’s population - were recently classified as undernourished. While as a percentage this represents a decline from previous years, the absolute number of undernourished people has been increasing since the period between 1995 and 1997, when 14% of the world’s population – or 792 million people – were undernourished. As the following and totally unsurprising map illustrates, the vast majority of these people live in the developing world. Indeed, given that the UN Department of Economic and Social Affairs external pageestimatescall_madethat the world population will increase from 7 to 9 billion by 2050 – with most of the two billion being added in developing countries – the raw number of undernourished people will increase in the future.

The Food Price Index

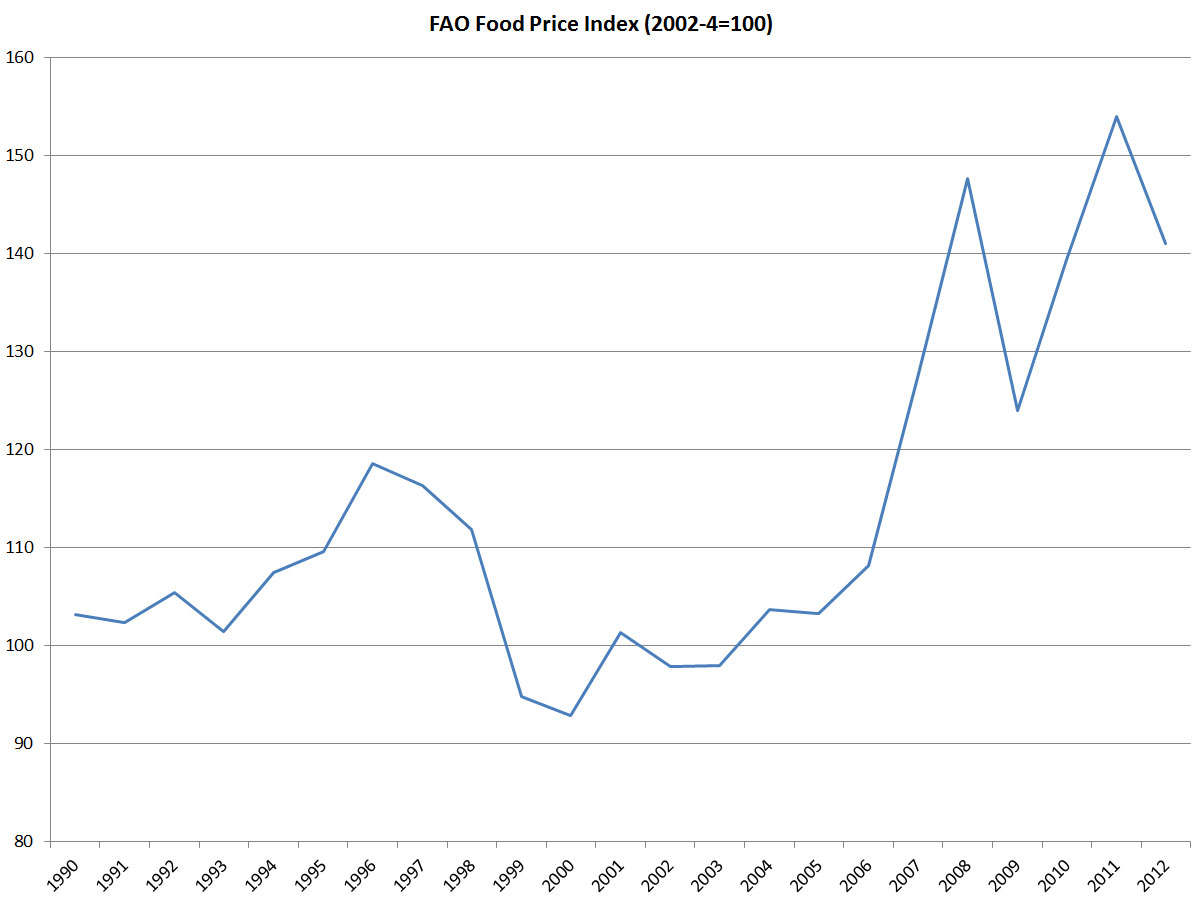

The above numbers are indeed troubling, but they become more so when they are coupled to food prices. Indeed, a useful indicator of food security is the price of food commodities, primarily because the latter reflects the relationship between the demand for and the supply of food. Consider, for example, the following changes in the Food and Agriculture Organization’s (FAO) external pageFood Price Indexcall_made, which measures international prices of a basket of food commodities, between 1990 and 2012. The sharp increase in prices between 2005 and 2008 reflects a ‘ external pageglobal food crisis’ that seemingly peaked in 2007-2008call_made, but which has not seen the erasing of the almost 50 per cent rise in food costs that occurred between 2002 and 2008.

The Return of Food Insecurity

Given all the above numbers, it shouldn’t surprise us that food insecurity apparently increased throughout the world in 2012, thus prompting analysts toexternal pagewarncall_madethat external pageyet another global food crisiscall_made is on the horizon. The most recent rise in prices was caused by a variety of unfavorable conditions in major food exporting countries. In Russia, for example, a external pageheat wavecall_made led to a significant decrease in crop yields and subsequent fears of a new government ban on grain exports. Likewise, in the United States external pagedroughtscall_madehave made a telling contribution to significantly lower food production and exports. When conditions like these occur in several major food exporters at once, global food prices unsurprisingly rise and they rise dramatically.

They also rise, to cite one example, because a high percentage of global grain exports come from a small number of countries, including the United States, Australia, Canada and Russia. If the top-15 exporters of wheat (see the following chart) experience further disruptions in 2012, either as a result of extreme weather conditions or government policies, the impact upon food security worldwide will obviously be aggravated further.

Country

Projected Exports (in 1000 metric tonnes)

1

United States

32,659

2

Australia

21,000

3

Canada

19,500

4

EU-27

17,500

5

Russian Federation

8,000

6

Kazakhstan

7,000

7

Argentina

5,500

8

India

4,500

9

Ukraine

4,000

10

Turkey

3,500

11

Brazil

1,500

12

Uruguay

1,300

13

Paraguay

1,200

14

China

1,000

15

Pakistan

800

Data source: external pageindex mundicall_made, external pageUnited States Department of Agriculturecall_made

Yet despite the above dangers, a food price crisis does not necessarily mean that there is insufficient food for everyone in the world. On the contrary, it may simply mean that fewer people have access to food because they can no longer afford to purchase it due to rising prices, or because corrupt brokers are withholding stocks to manipulate prices further, or because distribution systems are continuing to operate badly, either by design or not. Regardless of the reasons behind the shortages, it is undeniable that developing countries tend to be more seriously affected than the developed world. This is because increases in food prices have a bigger impact on lower-income households than on their higher-income counterparts. European citizens, for instance, spent external pageless than 13call_made per cent of their total household incomes on food in 2006. However, because global food prices converge to a greater degree than global incomes, in poorer countries external pagepeople can spend as much as half of their incomescall_made on food, with the figure being the highest external pagein parts of Sub-Saharan Africacall_made. This explains why people living in external pagedeveloping countries are much more vulnerable to increases in global food pricescall_made than those living in rich ones.

Beyond Price Volatility

Though external pageprice volatilitycall_made remains a serious threat to food security in many countries, it is only a symptom of the underlying causes of food insecurity. In the following video, Mark Rosegrant, of the external pageInternational Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI)call_made, outlines the food security challenges that the world faces in the coming decades and beyond. In addition to discussing problems associated with population and income growth in developing countries (which drives demand for higher-value foods such as meat, fish, fruits, and vegetables), he also discusses the implications of increased demands on land and water resources worldwide, with a particular emphasis on problems associated with climate change. Finally, Rosegrant concludes that broad-based income growth is needed to ultimately reduce food insecurity. This, he argues, will require targeted investment in increasing productivity, especially in the agricultural sector.

[Resource Embedded:153270]

The IFPRI video does confirm that many food security challenges have not yet received adequate responses at either the global or local level. In our final video, our partners at the Centre for Global Governance Innovation (CIGI) discuss a broad range of problems associated with food security and the prospects for finding sustainable solutions for them. The issues addressed include the complexity of food security governance (including the need for better coordination between international governmental organizations), the need to reduce world food price volatility, the need for systemic changes to the global financial system, and the need for greater research and development in a wide variety of areas related to food security.

[Resource Embedded:153276]