“Water Wars”: Past, Present and Future

17 Oct 2012

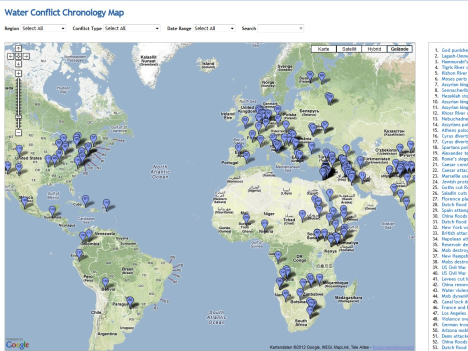

As Scott Moore alluded to yesterday, conflict over freshwater resources is as old as civilization itself. From the first (and only) recorded water war – between the Sumerian city-states of Lagash and Umma in 2500 BC – to the present, water-related violence has assumed a variety of forms. To cite just a few examples, it has involved water supply diversion and sabotage, strategic flooding (for military purposes), and civil unrest driven by limited access and distribution options. In today’s feature, we examine the past and future of water conflict and water-related violence. We begin with a geographical and historical overview of the 225 water-related incidents that have been compiled by Worldwater.org. As their Water Conflict Chronology Map illustrates, virtually all the incidents profiled (with the one exception mentioned above) fall significantly short of qualifying as a full-blown water war.

Despite the dubious popularity of the water wars thesis, and the increased strain that climate change will place on water resources in the coming years, the established historical pattern of water conflict is unlikely to change. Water wars, in other words, will become no more likely in the future than they have been in the past. As the University of Maryland’s Ken Conca indicates in the following interview with the Woodrow Wilson Center’s Geoff Dabelko, the future of water conflict is unlikely to involve conventional armies colliding with each other in order to secure scarce supplies in contested river basins. On the contrary, water conflict will become even more diffuse and decentralized in nature. According to Conca, three main types of conflicts are likely: 1) those between development-minded governments and communities adversely affected by large projects, such as the construction of dams; 2) those where the terms and conditions of access to water change across whole societies, particularly when poor communities lose access to water supplies after they have been privatized; and 3) those where dramatic transformations occur in water ecosystems – both as a result of climate change and development policies – and thereby threaten vulnerable communities.

[Resource Embedded:153826]

To help you draw your own conclusions as to whether Conca’s arguments provide a plausible alternative to the water wars thesis, we conclude by presenting in-depth profiles of existing water conflicts in South and East Asia. Nick Langton and Sagar Presai of the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) first ask whether conflict over water scarcity will play a defining role within South Asia in the future. Next, Hari Bansh Jha of the Institute for Defense Studies and Analysis (IDSA) in New Delhi focuses more broadly on the possibility of conflict between China and other Asian nations over water sources in the Tibetan plateau. Both case studies, it should be noted, are not only of interest today, but they also set the scene for tomorrow’s feature, where we take a closer look at the challenges posed by water scarcity to the security of the Middle East.

.jpg)