Modern War – Its Present Status and New Identity

3 Dec 2012

By Peter Faber for ISN

Europe's Optical Illusion first appeared in 1909, although it was later reprinted as external pageThe Great Illusioncall_made. Its author, Norman Angell, would later win the 1933 Noble Peace Prize and was very much a child of the Enlightenment. In his view, economics was more powerfully linked to peace rather than to war. Indeed, the more industrial nations traded with each other, the more their mutual interdependencies would grow. Attacking another nation, in other words, was now tantamount to shooting yourself in the economic foot. This did not mean that war between trading states was impossible; it merely meant that it had become self-defeating. And since attacking someone else meant you were attacking yourself, at least economically, it was only a question of time before militarism, war, and even conquest would start to wither on the vine. Their socio-economic utility would inevitably decrease, or so the argument went.

Although some aspects of Angell's argument have dated, his discussion of economic interdependence remains part of a rich polemical-philosophical history. Indeed, his unique brand of economic determinism looked back to the 18th century philosophes and forward to a European Union that continues to embrace “Norman Angellism” as one of its core principles. But has economic globalization, the semi-successful promotion of transnational legal-ethical norms and expanded notions of human or even civilizational-level security actually impacted the practice of war? In other words, either as an instrument of state or of private gain, has war recently lost its economic and socio-political utility?

The Present Status of War

Well, the data is sometimes more ambiguous than the progeny of Jean Jacques Rousseau, Norman Angell or pioneering cultural anthropologists would have us believe. (The latter three believed that there is nothing ‘eternal’ or ‘innate’ about war. It is a humanly created cultural artifact; it can be unlearned as readily as it can be embraced.) According to researchers at the Uppsala Data Program (UCDP), for example, 2011 was not a particularly good news story, or was it? On the debit side, we have the following truths to consider.

- The number of armed conflicts in the world increased from 31 to 37, an almost 20% rise and the largest increase between any two years since 1990.

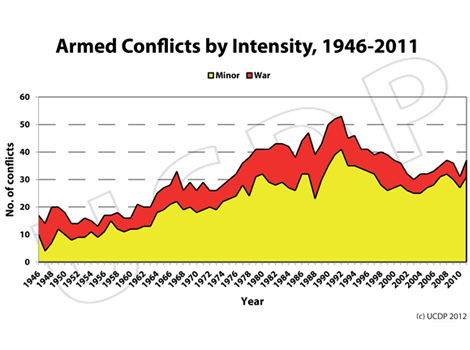

- 2011 also saw an increase in the most severe conflicts. By passing the accepted threshold of at least 1,000 battle-related deaths, six conflicts were categorized as wars. (This total is up from four in 2010 and includes Afghanistan, Libya, Pakistan, Somalia, Sudan and Yemen.)

- Finally, only one new peace agreement was signed in 2011, which is the lowest number since 1987 and which fell apart after three days.

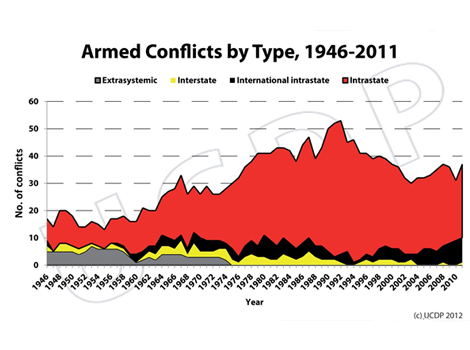

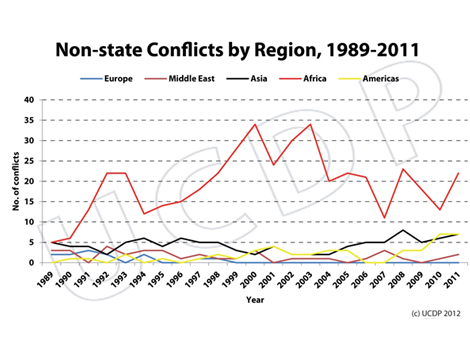

And yet, as the following graphs illustrate, one could argue that last year’s jump in violence represents a mere deviation from a long-term trend towards greater peace.

- For example, the number of “minor” conflicts and wars over the last decade has stabilized around roughly 30-40 per year, which is far below the peak years of the early 1990s. (The highpoint was 53 in 1993.)

- Extra-systemic wars (i.e., anticolonial ones) have basically disappeared and interstate wars are truly negligible in number. (The lone one in 2011 pitted Cambodia against Thailand).

- In the case of the dominant form of organized violence today – intrastate conflicts – the overwhelming majority of them are concentrated in portions of Africa, Asia and the Mexico-to-Columbia portion of the Americas.

- “Conflict episodes” that have lasted five years or more have become less common in recent years. Indeed, roughly 80 percent of the more recent conflict outbreaks were followed by less than five years of continuous fighting. Ah, but wait, demand the critics. Aren’t most conflicts today increasingly episodic? Yes, a substantial number of them are indeed “on-and-off affairs.” Recurrences of earlier civil wars now make up almost 80 percent of all conflict episode outbreaks. Nevertheless, when you add up the total number of active years spread over a number of episodes, the trend towards shorter conflict duration in recent history still holds true.

So, is the trend line favorable to the Norman Angell’s of the world, along with their norms-promoting brothers and sisters? It appears so, but the progress we are experiencing is not friction-free; it remains, as it always has, a 'two steps forward, one step back' process.

The Evolving Character of War

Now, if trying to divine the present relevancy or relative stature of war requires us to hack our way through a statistical briar patch or two, we certainly won’t experience similar ambiguities when contemplating the character of modern warfare. If anything, the ambiguity resides in the competing characterizations that have proliferated over the years. They include but are hardly restricted to the following:

- external pageNon-Obvious Warfarecall_made, as promoted by Martin Libicki;

- external pageWar Amongst the Peoplecall_made, as articulated by Rupert Smith;

- external pageNarrative Warfarecall_made, as indirectly discussed by Mary Crannell and Ben Sheppard.

- external pageHybrid Warfarecall_made, as presented by Frank Hoffman;

- external pageLawfarecall_made, as developed by Charles Dunlap, Jr.;

- external pageUnrestricted Warfarecall_made, as infamously advocated by Qiao Liang and Wang Xiangsui;

- external pagePost-Heroic Warfarecall_made, as propounded by Edward Luttwak;

- external page4th Generation Warfarecall_made, as conceived by William Lind, T. X. Hammes and others.

- external pageAnd Decision Cycle Dominancecall_made, as conceptualized by the great John Boyd and wisely external pageanalyzed by Frans Osingacall_made.

I leave it to the interested reader to mull over these engaging seminal texts and the various “new warfares” they’ve presented over the last twenty years. When stripped to their bare essentials, however, what these new ‘takes’ on war all point to, along with other prominent approaches not included here, is a simple truth – i.e., 1) for roughly two centuries we collectively privileged a particular type of war over all others – Napoleonic-Industrial Warfare; 2) this particular paradigm of war was so dominant that we came to confuse it with war itself; and 3) the paradigm became highly ritualized and overwhelmingly focused on large-scale force-on-force violence. And yet, as the Cold War evolved and then faded into history, more elastic foes and threats came to the fore. external pageAccording to David Kilcullencall_made, therefore, we now face enemies who:

- “Integrate terrorism, subversion, humanitarian work, and insurgency to support propaganda designed to manipulate the perceptions of local and global audiences.

- Aggregate the effects of a very large number of grassroots actors, scattered across many countries, into a mass movement greater than the sum of its parts, with dispersed leadership and planning functions that deny us detectable targets.

- Exploit the speed and ubiquity of modern communications media to mobilize supporters and sympathizers, at speeds far greater than governments can muster.

- Exploit deep-seated belief systems founded in religious, ethnic, tribal, or cultural identity, to create extremely lethal, non-rational reactions among social groups.

- Exploit safe havens such as ungoverned or under-governed areas (in physical or 'cyber' space); ideological, religious, or cultural blind spots; or legal loopholes.

- Use high-profile symbolic attacks that provoke nation-states into overreactions that damage their long-term interests.

- Mount numerous, cheap, small-scale challenges to exhaust us by provoking expensive containment, prevention, and response efforts in dozens of remote areas.”

With such threats now facing us, the various warfares previously listed here aren’t so much a Babel of Voices as they are a necessarily holistic response. The Napoleonic-Industrial model of war may indeed still be applicable for a limited number of 21st century scenarios, but it is no longer sacrosanct. The “combat zones” are now in new domains – the law, in the narratives one develops, in the electromagnetic spectrum and so much more. And the point of the ‘combat’, according to Rupert Smith, is now either to capture the minds of the people or to create those conditions through which your desired results might be found by other means. Well, there’s at least one thing we can say about all this – this isn’t your father’s war anymore.