The Horn of Africa Security Complex

9 Sep 2013

By Berouk Mesfin for Institute for Security Studies (ISS)

Editor's note: the following excerpt is the first chapter of the report Regional Security in the Post-Cold War Horn of Africa, originally published by ISS Africa in April 2011.

Introduction

This chapter is the product of more than a decade of research conducted by the author on the Horn of Africa, and draws on his numerous discussions with foremost analysts and top-level decision-makers[1] whose policies are increasingly influenced by regional politics. It also derives from the frustration of the author, who has seen particular overblown, trivial issues – such as the irrepressible obsession with piracy – being amplified, whereas more pressing and substantive security challenges, such as the lethal danger of ferocious and irreducible conflicts, are being benignly disregarded. Such a confounding situation has simply made the author fear for the long-term security of the region. As a result, the author has tried to generally summarise and synthesise the conflicts and security dynamics in the Horn of Africa from a regional perspective and for the past five or six decades.

Nonetheless, explaining the environment and dynamics of regional security is necessarily an arbitrary exercise for students of international relations, [2] depending on which elements appear to them as most significant and on the prevalent political and strategic realities. Fortunately, Barry Buzan offers a strong conceptual framework. From the perspective of this chapter’s author, this conceptual framework provides an adequate unit of analysis that facilitates comparison and generalisations to a very high degree. It has also enabled the author to offer, in the simplest way possible, deeper insights into the security trends in the Horn of Africa and to tell the bigger picture without directly applying the conceptual framework to materials of the region. Accordingly, this chapter will first outline, as briefly as possible, the major tenets of Buzan’s conceptual framework. It will then proceed to provide a basic definition of the region known as the Horn of Africa and explain, in greater detail, the major elements and patterns of regional politics within it.

What is a security complex?

First published in 1983 and republished in 1991, Buzan’s pioneering study, People, states and fear, was the first sustained and serious attempt to put forward guiding ideas pertaining to the concept of regional security.[3] One major benefit of Buzan’s conceptual framework is that it enables analysts to challenge prevalent conceptions and ‘talk about regional security in terms of the pattern of relations among members of the security complex’.[4] The following is a brief consideration of Buzan’s most significant precepts rather than a comprehensive survey of his conceptual framework.

In the first place, and in security[5] terms, Buzan argued that a region means that ‘a distinct and significant subsystem of security relations exists among a set of states whose fate is that they have been locked into geographical proximity with each other’.[6] Moreover, military and political threats are more significant, potentially imminent and strongly felt when states are at close range. Buzan stressed that regional security systems such as those of South Asia, for instance, with its military stand-off between India and Pakistan, can be seen in terms of balance of power as well as patterns of amity, which are relationships involving genuine friendship as well as expectations of protection or support, and of enmity, which are relationships set by suspicion and fear, arising from ‘border disputes, interests in ethnically related populations [and] long-standing historical links, whether positive or negative’. [7]

According to Buzan, these patterns are confined in a particular geographical area. Buzan used and popularised the term ‘security complex’ to designate ‘a group of states whose primary security concerns link together sufficiently closely that their national securities cannot realistically be considered apart from one another’.[8] Such complexes ‘are held together not by the positive influences of shared interest, but by shared rivalries. The dynamics of security contained within these levels operate across a broad spectrum of sectors – military, political, economic, societal and environmental’.[9]

Buzan’s conceptual framework provides meaningful insights both into how different types of conflict suddenly erupt and quickly spread in space and time, and also into the interplay between these different types. Security complexes are exposed to four major types of threats and their interaction: balance of power contests among great powers; lingering conflicts that emerge between neighbouring states; intra-state conflicts, which are usually spillovers of internal politics; and conflicts that arise from transnational threats caused, for instance, by the rise of radical Islam and informal networks, state fragility, demographic explosion, environmental degradation and resource scarcity.

The Horn of Africa

Delineating the Horn of Africa

In a narrow geographic sense, the Horn of Africa is that north-eastern part of the African continent which faces the Red Sea to the east, the Indian Ocean to the south-east and the Nile Basin to the west. The Horn of Africa conventionally comprises the key states of Ethiopia, Somalia and Djibouti, although it embraces geopolitically the adjoining states of Sudan and Kenya.[10] It should also be pointed out that Uganda,[11] which is a member of the Intergovernmental Authority on Development (IGAD), and Yemen, Libya and Egypt are no less involved in the issues and processes of the region and certainly have an impact on power balances and developments. All these states share social and cultural values emanating from a centuries-old tradition of interrelationships, common religious practices and economic linkages. Furthermore, the political fate of each state in the region has always been inextricably intertwined with that of neighbouring states. Indeed, no individual state in the Horn of Africa has been insulated from the other states’ problems, irrespective of their distance and comparative strengths or weaknesses.

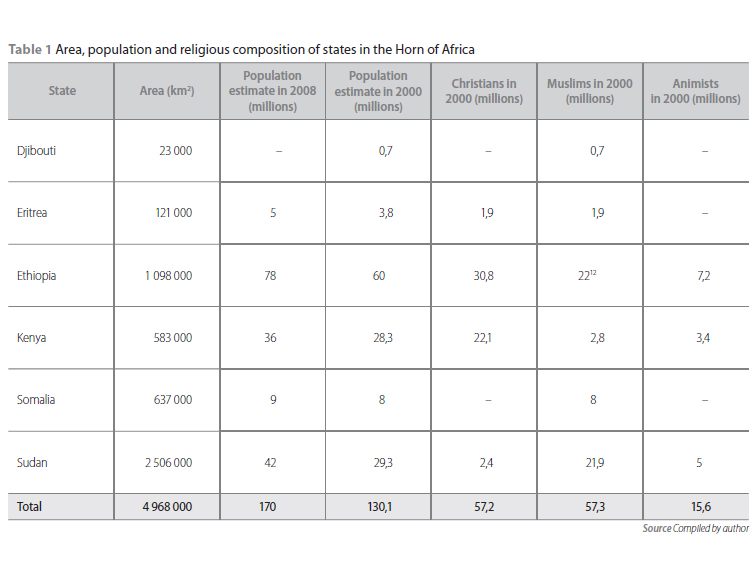

The six states which make up the Horn of Africa cover an area of around five million square kilometres and had in 2000 a total population of about 130,1 million, which grew to 170 million in 2008. The region’s average population growth rate of not less than 2,9 per cent is one of the highest population growth rates in the world, and nearly half of the population is under 14. In 2000 in the Horn of Africa, which is the meeting point between Muslim, Christian and Animist cultures, Muslims constituted a slight majority, making up some 44 per cent of the total population; 43 per cent were Christians. [12]

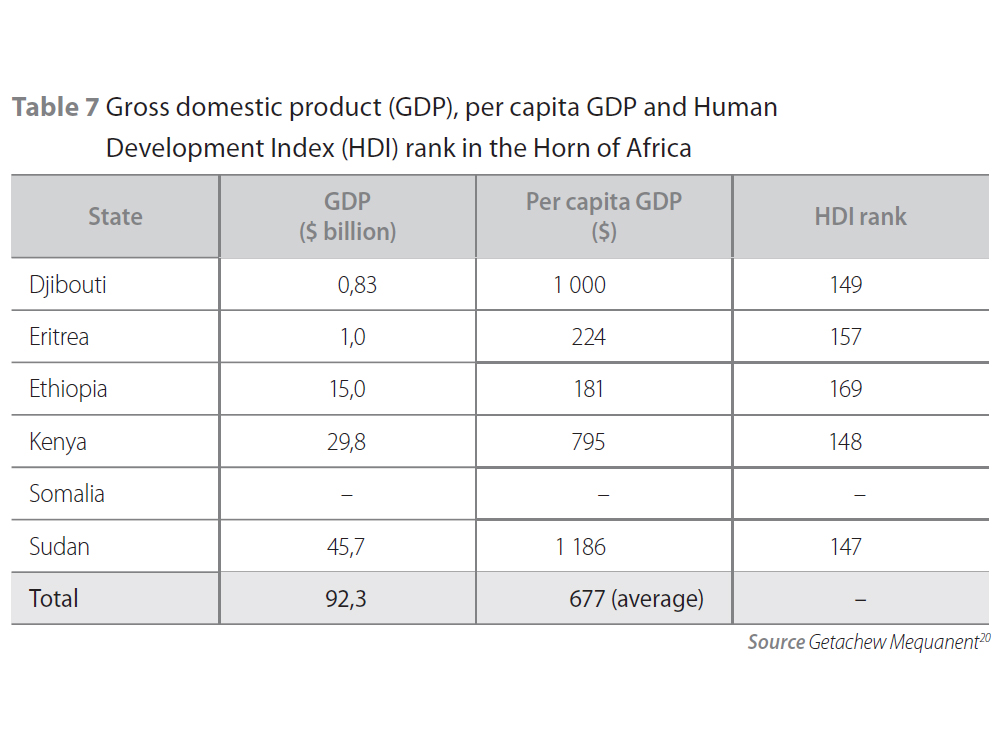

The Horn of Africa can be characterised as the most deprived and poorest region in Africa, if not in the world (see Table 7). It is a region where the most basic necessities (clean water, food, healthcare and education) are not available to the majority of the population. In the Horn of Africa, per capita income, life expectancy and literacy are among the lowest in the world, and adult and infant mortality are among the highest. The region is prone to deadly droughts that hamper crop and livestock production. These droughts result in food deficits each year, thereby making the Horn of Africa one of the regions with the greatest food insecurity in the world. In 2008 in the Horn of Africa, an estimated 17 million people were in need of emergency assistance. [13]

Furthermore, the Horn of Africa is the most conflict-ridden region in the world,[14] with conflicts – exacerbated by external interference and accompanied by widespread human rights violations – raging sometimes simultaneously within and between states. In fact, the African continent’s longest-running intra-state conflicts – in Eritrea and South Sudan, with an estimated death toll of over two million – took place in the Horn of Africa. It is also generally held that, due to the aforementioned disasters, both natural and artificial, the Horn of Africa has the highest percentage of refugees – estimated to have reached 700 000 in 2003, which is roughly equivalent to Djibouti’s population – and internally displaced people in Africa, a trend that reinforces future cycles of conflict. In 2008, the total number of internally displaced people in Kenya, Somalia, Ethiopia and Uganda was estimated at 2,74 million, out of which an estimated 1,3 million were displaced in Somalia, which is one of the world’s worst humanitarian disasters.[15] In 2010, in Sudan alone there were more than four million internally displaced people, virtually Eritrea’s entire population.[16]

[Table 1 Area, population and religious composition of states in the Horn of Africa]

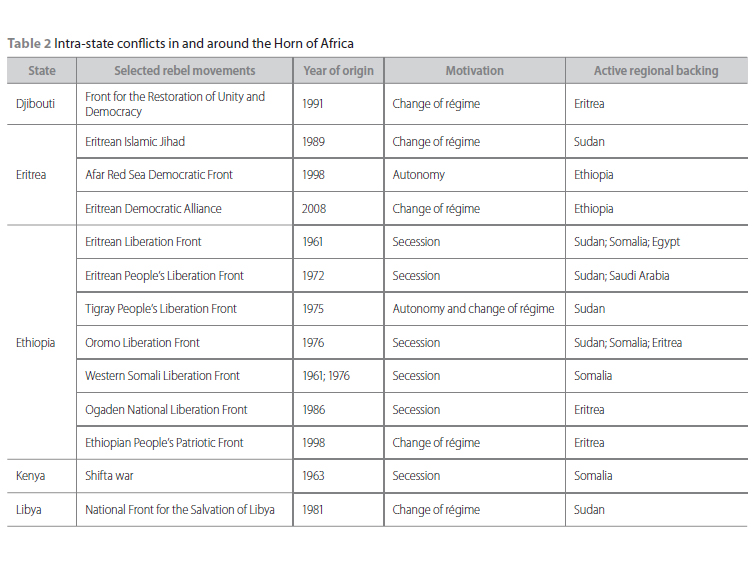

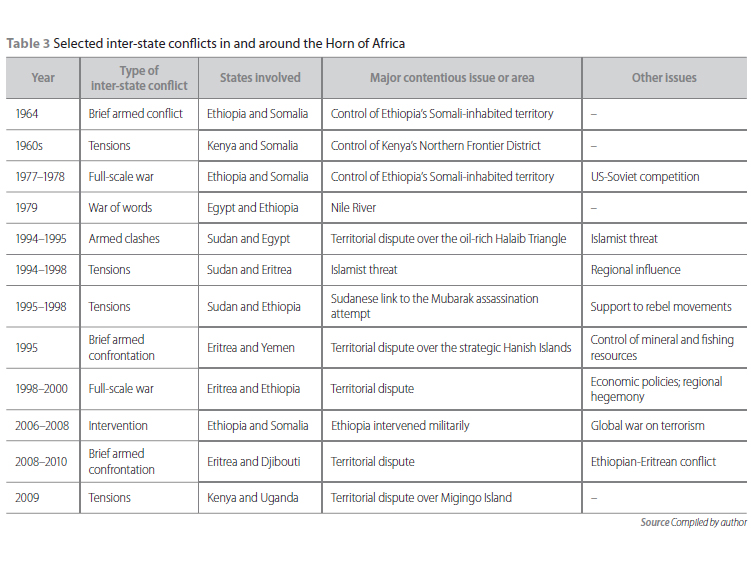

[Table 2 Intra-state conflicts in and around the Horn of Africa - 2 parts]

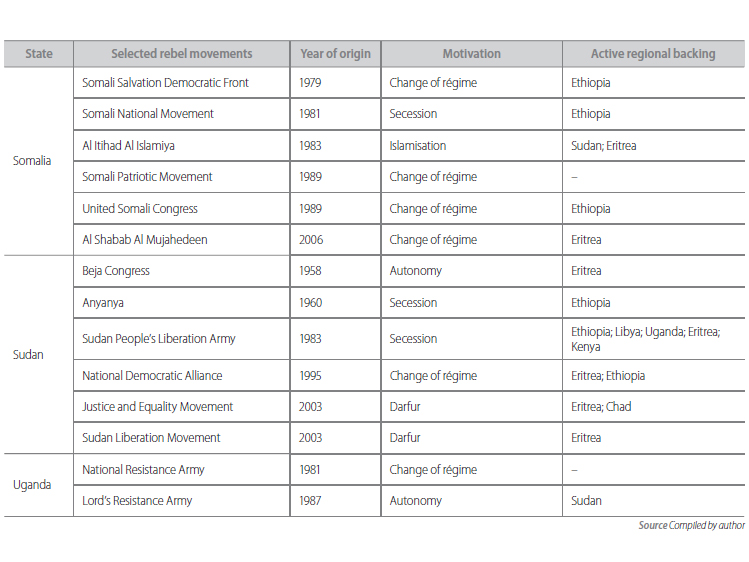

[Table 3 Selected inter-state conflicts in and around the Horn of Africa]

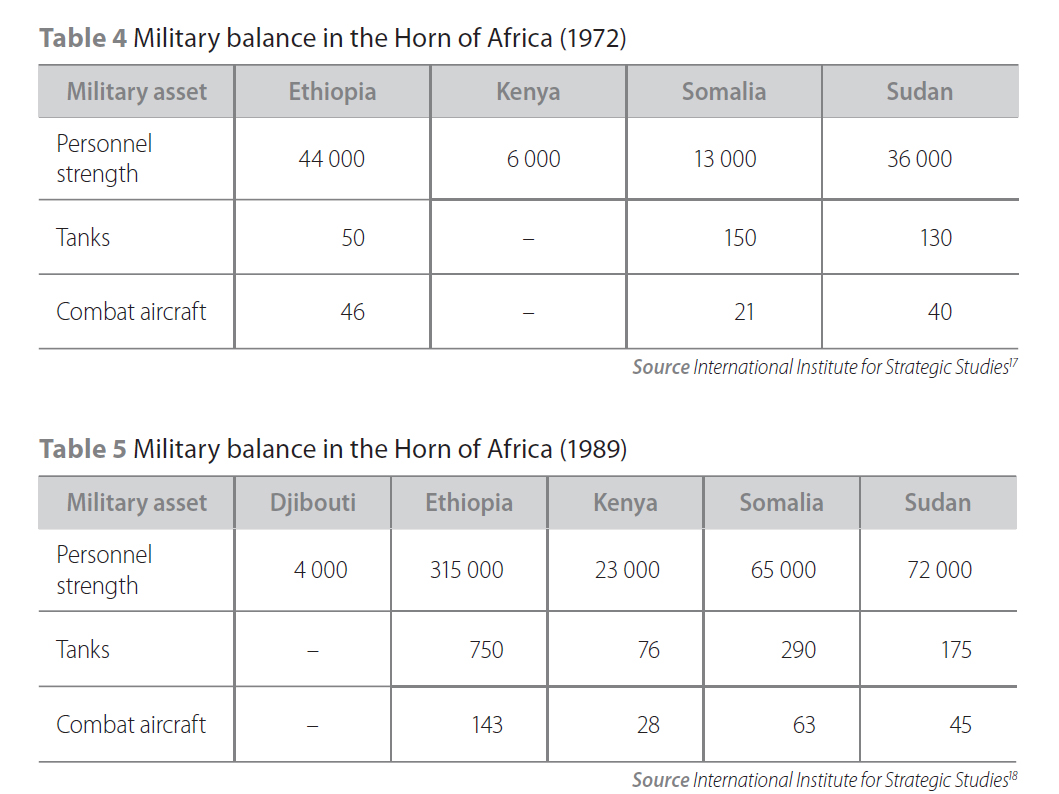

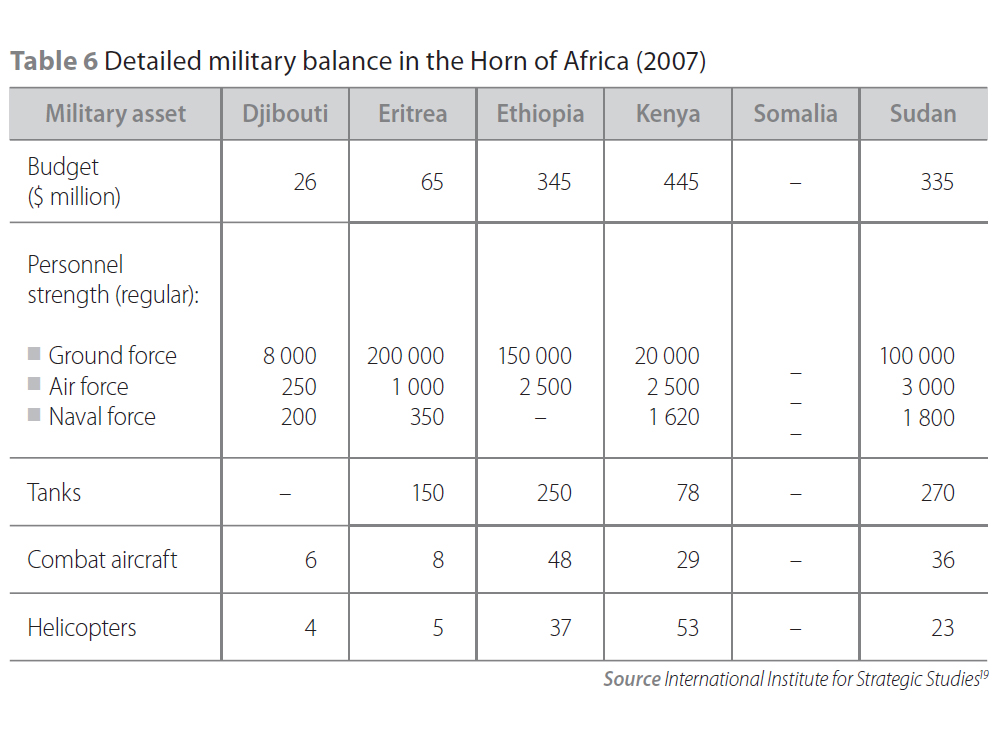

[Table 4 Military balance in the Horn of Africa (1972) and Table 5 Military balance in the Horn of Africa (1989)]

[Table 6 Detailed military balance in the Horn of Africa (2007)]

[Table 7 Gross domestic product (GDP), per capita GDP and Human Development Index (HDI) rank in the Horn of Africa]

The colonial legacy

The seeds of the current conflicts in the Horn of Africa to a large extent go back to the European colonial experience in that region, even though most of the conflicts’ root causes pre-date this experience.[21] Indeed, at the end of the 19th century and after the construction of the Suez Canal,[22] the European colonial powers partitioned the previously free constituent parts of the Horn of Africa, joining unrelated areas and peoples into territorial units. The establishment of new states (Sudan got its independence in 1956, British and Italian Somaliland in 1960, Kenya in 1963, and Djibouti in 1977, whereas Eritrea was federated with Ethiopia in 1952 and forcefully gained its independence in 1993, leaving Ethiopia landlocked) was, therefore, based on misdrawn borders which were agreed upon by the colonial powers and basically ignored ethnic, cultural, historical and religious groups’ natural lines. As a consequence, this gave rise to intra-state conflicts (in particular, demands for autonomy from ethnic groups) and to the regimes of the newly independent states lodging territorial claims, which, in turn, led to conflict with other states.

The challenge was compounded by the fact that the framework of colonial laws and institutions had been designed to exploit local divisions rather than to overcome them. Colonialism also disrupted the political, social and economic lives of pastoral societies. The emergence of colonial ports as well as the development of modern transport systems disrupted the ancient trade networks on which pastoralists depended, and coastal markets disappeared in many cases. Moreover, transportation networks and related physical infrastructure were designed to satisfy the needs of the colonial powers rather than support the balanced growth of an indigenous economy. During the same period, by taking advantage of inter-European rivalries, the Ethiopian rulers doubled through conquest the geographic size of their independent state built on the interior highlands. A vast, multi-ethnic state was created there. The need to maintain intact the unity of this fragile and disparate entity led to the excessive centralisation of political and economic power, which, in turn, stimulated widespread infringement upon local cultures and led to religious coercion and political repression.

Conflicts were also triggered by ethno-centrism arising from colonial rule, which favoured certain ethnic groups by according them access to education and economic privileges. This was at the expense of other ethnic groups in the context of the divide and rule tactics employed by the colonial powers, and inflicted deep societal wounds in some states. In the post-colonial era, ill-advised policies have entrenched colonially designed disparities and chronic injustice, thereby worsening ethnic animosities and antagonisms in most states of the region. Such a legacy lives on especially in Sudan, where a pernicious conflict was resuscitated in 1983 as a result of former president Gaafar Nimeiri’s imposition of Sharia or Islamic law on all segments of the Sudanese population – Muslims, Christians and Animists alike. The widely perceived racial and religious discrimination against the mainly Christian and Animist black Africans in South Sudan by the mainly Muslim Arabs from Sudan’s north and the latter’s control of Sudan’s governing regimes and economy contributed largely to the commencement of the conflict. This conflict, which provoked an influx of refugees into neighbouring states, including Ethiopia, presented the post-1974 Ethiopian regime with the opportunity to reciprocate Sudan’s support for the Ethiopian rebel movements by giving support to the rebel movement emerging in Sudan.

Political and economic problems

In the Horn of Africa, the nature of state power is a key source of conflict: political victory assumes a winner-takes-all form with respect to wealth and resources as well as the prestige and prerogatives of office. Irrespective of the official form of government, regimes in the Horn of Africa are, in most cases, autocracies essentially relying on ethnic loyalties. The military and security services, in recent times emerging from a liberation-front background, ensure the hold on power of these militarised regimes.[23] By default, a controlled – not to speak of peaceful – change of power is an exception. And insufficient accountability of leaders, lack of transparency in regimes, non-adherence to the rule of law, and the lack of respect for human and people’s rights have made political control excessively important and the stakes dangerously high.

Also, given the highly personalised milieu in which politics operates in the Horn of Africa, ‘strong-man benevolent leader[s]’ [24] in the likes of Mengistu Haile Mariam, Gaafar Nimeiri or Siad Barre, who were all deeply insecure behind their ruthlessness and vindictive egomanias, were able to shape the political destiny of a state almost single-handedly and enter into either warm or conflictual relations with other states, inducing civilian populations to join in and converting them into military and paramilitary groups. [25] In fact, despite the devastation they brought, such leaders and their behind-the-scenes operators used senseless conflicts to divert popular impatience at their inability to improve conditions. Moreover, these states suffer from a lack of trained personnel who can muster a long-term vision and possess experience in security policy-making and management; such people prefer to go abroad in order to better their lives or escape systematic maltreatment. Leaders exploit the international community’s laissez-faire attitude and turn deaf ears to the advice of professional policy advisors and opinion-formers. This automatically leads to what an observer of regional politics described as ‘short-term thinking’ [26] and clumsy ad hoc decision-making, and eventually to shocks such as the unanticipated Ethiopia-Eritrea war of 1998–2000.

Moreover, political competition in the Horn of Africa is not rooted in viable economic systems. All of the region’s states are barely capable of reaching a level of economic development at which even the basic needs of their populations are met. Economic activities are strongly skewed towards primary commodities for export, which are subject to the whims of the fluctuating prices of the international commodity markets. Economic activities are also hampered by external dependence, inadequate infrastructure, shortage of capital, shortage of skilled labour and misguided development policies. Compounding this, the state is unable to provide adequate health and education services or to remedy mass unemployment, which partly results from unsustainably high population growth.

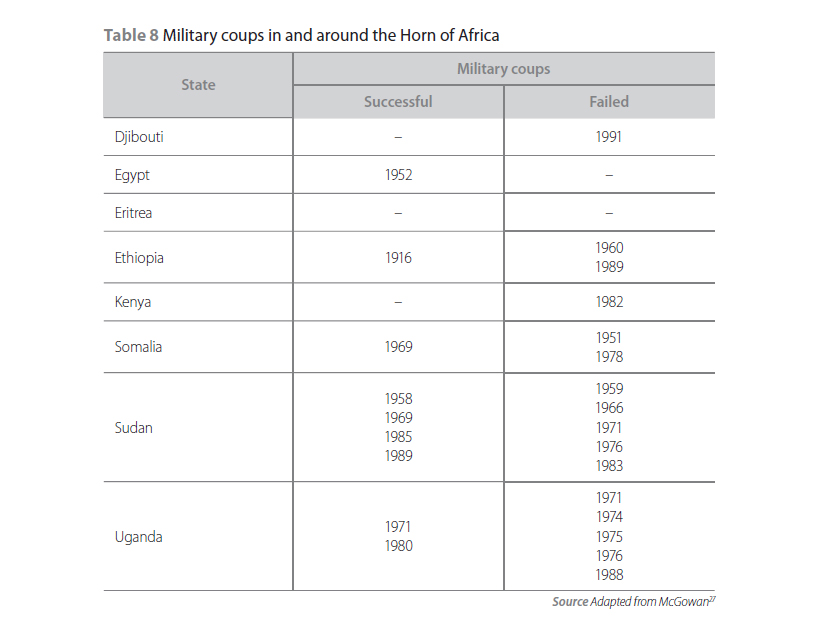

Furthermore, in order to hold on to power, hold the state together and defend it against the claims and attacks of other states and rebel movements, governing regimes build and maintain military forces of large dimensions (see Tables 4, 5 and 6). They spend a large share of national expenditure on the military in disproportion to their available economic resources and existing security threats. This kind of excessive militarisation eventually entails an increased burden, especially in present times of dwindling resources and economic crises. Excessive military spending is essentially wasteful, resulting in social projects in education or health remaining stagnant or even non-existent. It also heightens the perception of mutual threat, with a wide range of unintended political

[Table 8 Military coups in and around the Horn of Africa]

consequences. On the one hand, external threats will be used, as mentioned earlier, to draw attention from real internal problems; and on the other hand, a politicised, compromised and restless military with its proneness to usurp state power and resources represents a grave danger to inherently fragile regimes as well as their political and security structures.

Access to shared resources and environmental degradation

Even though the states of the Horn of Africa appear to be independent of each other, ‘there may have to be a sharing of resources. An obvious example is the flow of a river … but shared resources may also be reflected in the cross-border movements of pastoralists’. [28] The most prominent river is the Nile, which has always been an intricate part of the geopolitics of the Horn of Africa. Ethiopia, Sudan and Egypt are geographically partly owners and users of the river, and all three consider it a major security issue.[29] Egypt, in particular, totally depends on the Nile River’s waters for its very existence [30] and, therefore, ‘the first consideration of any Egyptian government is to guarantee that these waters are not threatened. This means ensuring that no hostile power can control the headwaters of the Nile or interfere with its flow into Egypt’. [31]

Accordingly, Egypt repeatedly made it crystal clear that it would resort to the threat of military action [32] to preserve its portion of the Nile River (the 1959 Egyptian-Sudanese Treaty allocated 55,5 billion cubic metres of the river to Egypt), even though, ‘owing to a combination of political and economic conditions and technological limitations in [c]entral and [e]astern Africa, this threat fortunately did not materialise for a long time’.[33] For instance, after signing a peace treaty with Israel in 1979, Egypt’s late president Anwar Sadat issued a stern warning which was well noted in Ethiopia and according to which ‘the only matter which could take Egypt to war again is water’.

This policy was aimed at preventing upstream states, especially Ethiopia, which contributes more than 80 per cent of the water flowing to Egypt, from claiming their share of the Nile River’s total water. Furthermore, being the Arab world’s most populous, politically influential and militarily strongest state, Egypt entertained the long-established ambition of projecting its power towards the Red Sea. Ethiopia was exposed to this geopolitical projection, which included overt support for the Eritrean Liberation Front, established in Cairo in 1961, military support for Somalia during the 1977–1978 Ogaden war, military support for Eritrea during the 1998–2000 Ethiopia-Eritrea war and short-circuiting Ethiopia’s IGAD-mandated mediation in Somalia during the mid-1990s. Indeed, a military pact was signed in 1976 between Egypt and Sudan following which Egypt stationed troops in Sudan, trained its military personnel and undertook joint military planning so that, in the case of aggression against one, the other would come to its rescue. Clearly, Egypt regards Sudanese territory as providing added depth to its geopolitical objectives and is not comfortable with the idea of South Sudan attaining independence, as it ‘might jeopardise Nile security’.[34]

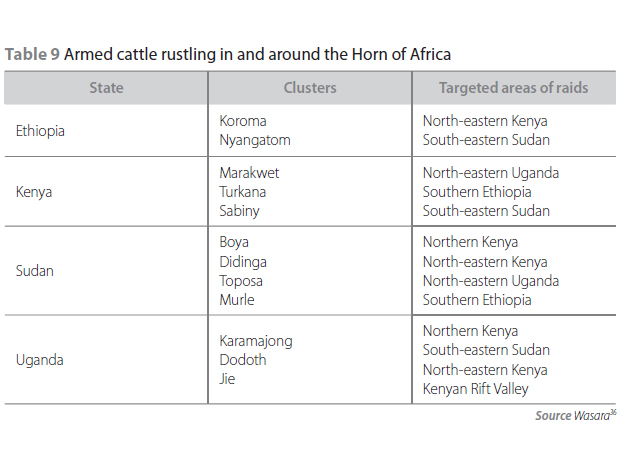

In addition, pastoralists have to be constantly on the move in search for areas that offer better water and grass, which ignites conflicts among pastoralists and with sedentary agricultural communities in the Horn of Africa. However, the creation of artificial borders and states that are interested in controlling all movements and imposing taxes limited the size of available resources and disrupted the traditional movement patterns of pastoral societies.[35] Armed clashes, negative state policies leading to violently expressed grievances and recurrent droughts have led to an environmental crisis and the militarisation of pastoral societies, which, in turn, exacerbates inter-ethnic tensions. What happened in Darfur was partly an environmentally generated antagonism over shared

[Table 9 Armed cattle rustling in and around the Horn of Africa]

resources, such as water systems, woodlands and grazing land for livestock. As populations in Darfur and its surrounds increased and access to these resources became more acutely scarce, conflicts among communities erupted and became difficult to resolve.

The logic of subversion

The states of the Horn of Africa took advantage of every local tension or conflict to support rebel movements in neighbouring states. [37] Sponsoring subversive activities had simply become a customary tool poised to destabilise and endanger the security of another state, in what some observers called the time-honoured principle of ‘my enemy’s enemy is my friend’ extending throughout the Horn of Africa.[38] This enhanced inter-state rivalries, mutual suspicion and the development of an eye-for-an-eye mentality. One example is the long and bloody game of tit-for-tat that bedevilled relations between Ethiopia and Sudan for over four decades.[39] It is ‘impossible to prove who was the original culprit in this long-running proxy war’, [40] as ensuring the secrecy of the support’s details was paramount because a disclosure of its true extent would threaten its effectiveness and risk major embarrassment to the regimes. In any case, Sudan’s support for Ethiopian rebel movements was the reason why the Sudan People’s Liberation Army enjoyed strong and sustained support from the post-1974 Ethiopian regime.

Other examples abound in the Horn of Africa in which ‘pursuing regional foreign policy through proxy forces in neighbouring countries has been the normal pattern of relations for decades. This activity has proved persistent over time and has survived radical political reconfigurations, including changes of regime’.[41] ‘Mengistu engaged Barre in a proxy guerrilla war in which they each supported the other’s insurgent’.[42] The Christian fundamentalist Lord’s Resistance Army received support from Islamist Sudan in retaliation for Uganda’s support for the Sudan People’s Liberation Army. Sudan’s support for the Eritrean Islamic Jihad invited Eritrean support for the Sudan People’s Liberation Army and the National Democratic Alliance, which was even allowed to occupy the Sudanese embassy premises in Asmara. [43] It has to be pointed out that Eritrea has become a recklessly belligerent bully especially adept at pursuing a low-cost strategy of supporting rebel movements against Sudan and Ethiopia as well as in Somalia. Many analysts describe Eritrea’s support for the Somali Islamist movements – despite facing its own Islamist movement – as a proxy war that is largely opportunistic, as it cuts across ideological lines[44] (a case which will be developed in more detail in the following sections).

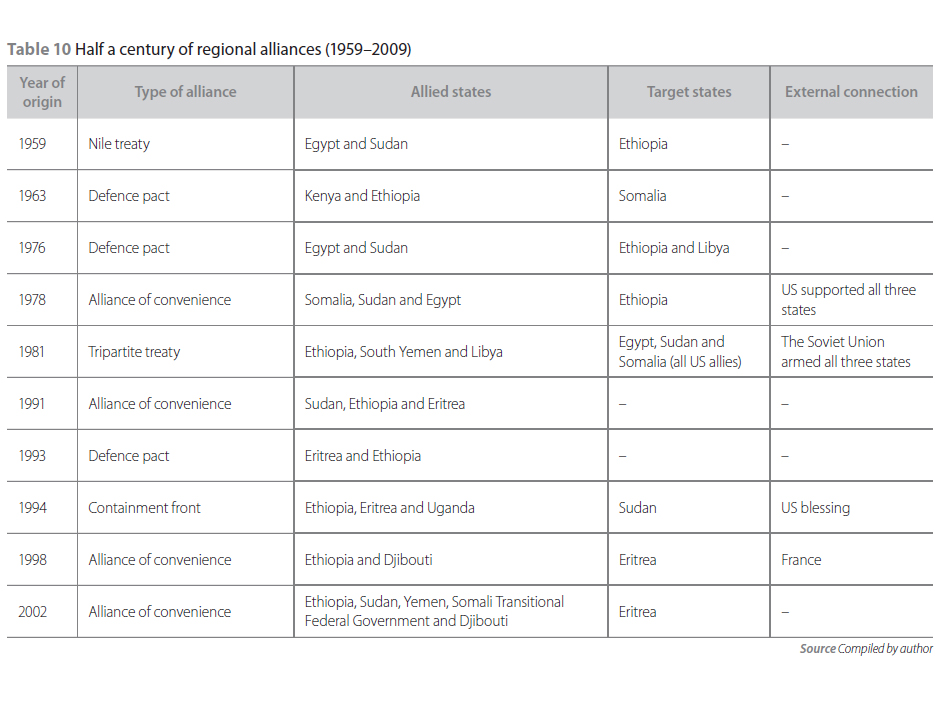

The logic of alliances

Alliances are usually assigned to prevent or contain external disruptions of security and to establish a viable equilibrium of forces in a region. [45] The formation of alliances, which is part of the balance of power system, is a strategy devised and implemented in conjunction with regional or external partners. In the Horn of Africa, alliances span a wide range of different configurations. They range from formal military alliances between leaders or regimes to state support for rebel movements in neighbouring states and further afield, or even alliances between rebel movements.[46] However, as in the case of subversion, alliances may not bring together like-minded partners, whose loyalties are by no means fixed, as they may be sometimes working at cross purposes. Every alliance ‘tends to have a logic of its own when once set in motion’[47] and accordingly cannot withstand the test of time (see Table 10). It is plausible to argue that one exceptional alliance that did stand the test of time and the Cold War’s realignments was the one established between Kenya and Ethiopia after they signed a military pact in 1963 aimed at neutralising Somalia.

In the Horn of Africa, opportunistic alliances had a relative restraining influence, but, equally, gave additional momentum for inter-state conflict. One classical alliance behaviour is provided by the vicious spiral of alliances and counter-alliances that emerged in the late 1970s at a time of tensions and violence in the region. US-supported Egypt, which was engaged in conflict with Soviet-supported Libya, helped Sudan and Somalia. Ethiopia, which was drawn into the socialist camp, fought Somalia, confronted Sudan and got associated with Libya by the 1981 Aden Treaty. Somalia was in effect supported by Egypt and Sudan in its claims on Ethiopian territory. Sudan, which was backed especially by Egypt, stood against its neighbours, Libya and Ethiopia. And Libya, which was not directly involved in territorial or other disputes in the Horn of Africa, helped the enemy (Ethiopia) of its enemy’s (Egypt’s) allies, Sudan and Somalia.[48]

The latest regional alliance is the Sana’a Forum for Cooperation, which was established in 2002 and is widely perceived as an ‘alliance of convenience aimed

[Table 10 Half a century of regional alliances (1959–2009)]

against Eritrea’.[49] It was initially a tripartite alliance involving Ethiopia, Sudan and Yemen, all of which had military confrontations with Eritrea and shared a deep-seated antipathy towards its regime. Sudan and Ethiopia especially think that ‘there can never be regional stability as long as Issayas dominates the Eritrean state’.[50] Somalia was also later included as a sideline partner, and Djibouti joined as an observer in 2008 after its bizarre border dispute with Eritrea.

The Horn of Africa’s strategic importance, and superpower interference

The Horn of Africa has never acquired a strategic importance for its raw materials or for any other continental advantage. [51] However, the region has always been allotted a relatively important strategic value owing to its proximity to the Red Sea, which is an important and expeditious route of international trade and communications between Europe, the Middle East and the Far East, as well as the navigation route through which oil is transported from the Persian Gulf (in which the largest oil deposits of the world are located) to consumers in North America and Europe.[52] Hence, the states of the Horn of Africa were forced into economic, political and military dependence on either one of the two superpowers of the Cold War – the US and the Soviet Union. Competing to establish positions of influence and military advantage in the strategically significant regions of the Persian Gulf and Indian Ocean, the two superpowers supported client states in the adjacent Horn of Africa primarily by injecting military aid, and undermined inimical states by supporting rebel movements and weaving unfriendly alliances and counter-alliances.[53]

The interests of the US can be explained in terms of securing access to oil for the West in the Arabian Peninsula and the Persian Gulf. It was, therefore, in the interests of the US to fend off any expansion of Soviet power and influence, whether through proxies or not, in the Middle East, Indian Ocean and the Horn of Africa. Conversely, the Soviet Union aimed at promoting its credibility as a superpower by influencing and over-arming the largest number of strategically placed client states,[54] imperilling oil tankers bound for the West via the Suez Canal and reducing to nil the influence of the US in the above-mentioned regions. Geopolitical logic also required the Soviet Union, which needed to have maritime staging areas for its rapidly increasing navy, to control the arc running from South Asia to the Horn of Africa. [55]

Terrorism

Since the mid-1990s, the states in the Horn of Africa have witnessed hundreds of acts of terrorism against foreign as well as local citizens and interests. The region is accordingly considered both as a breeding ground and a safe haven for terrorist organisations, especially after the September 11 terrorist attacks in the US in 2001. Hence, this region has come under increased scrutiny in the war against terrorism. For instance, Kenya, in which approximately 10 per cent of the population is Muslim (see Table 1), experienced the 1998 terrorist attack on the US embassy in Nairobi, the bombing of a Mombasa hotel and the missile attack on an Israeli commercial jetliner in 2002. These acts have accentuated the fear that Kenya’s Muslim-dominated coastal areas may fall under fundamentalist influence and affect the state’s internal structure and foreign relations, and exacerbate latent social and ethnic conflicts. [56]

In the wake of the terrorist attacks in the US, Somalia came under the watchful eyes of Western intelligence services and military forces. In view of Somalia’s lengthy and easily penetrable coastline and the prolonged absence of a functioning administration, the US worried that Al Qaeda might establish training bases or use it as a conduit for money, personnel and material for future terrorist operations beyond the Horn of Africa. Moreover, the increasing flexibility and speed of 20th century transportation and communications means that states could expect no warning ahead of terrorist attacks. Therefore, the US created a Combined Joint Task Force-Horn of Africa (CJTF-HOA) with an area of responsibility covering the Horn of Africa plus Yemen.

The US is bent only on reducing the ability of terrorist organisations to operate and move in the region. The actions of the US clearly show a discrepancy between its own interest of fighting terrorism in the Horn of Africa and that of the regional regimes, which have an utter disdain for US concerns. In fact, the diffusion of modern military technologies and state-of-the-art techniques of organisation, which the US approach entailed, went beyond the modernisation of the military or the transfer of weapons. It led to the institutionalised surveillance of entire populations and the blind, wholesale suppression of all political opponents, leading in effect to the diffusion of ideas, such as Islamist fundamentalism, with resultant security problems, particularly in Somalia. An observer of the Horn of Africa said that:[57]

Outside actors need to respond judiciously to the allegations of terrorism levelled against various parties to conflict in the Horn. The underlying conflicts in the region are older than the contemporary war on terrorism and will probably outlast it. Outsiders need to recognise the tactical value of their support and the interests at stake in representing local adversaries as associates of terrorism. They also need to weigh the possible gains (in terms of international terrorism) from intervention against the risks of greater radicalisation, alienation and conflict generation in the region.

Conclusion and prospects

The author tried to treat the Horn of Africa, which is ‘interlinked to an even greater extent than i[s] the case in other regions of Africa’, [58] as a unit of analysis in its own right, a unit that possesses its own internal dynamic process. He also tried to underline the importance of such a regional focus, which links both the internal and external determinants, to provide a better understanding of the dynamics of conflict in the Horn of Africa in which the unknown prevails and power is calculated in terms of available weapons. Only such an understanding can release a ‘this isn’t working’ attitude, leading to a whole new rethinking on several levels, in turn, leading to a ‘something must be done’ reaction, which may perhaps give the next generations of the Horn of Africa a better perspective on their future.

Indeed, ‘how security threats are perceived and articulated in the Horn of Africa could provide better insights into how the region actually works’.[59] For instance, the ‘seemingly irrational stances vis-à-vis neighbours’ [60] and the rapidity of the shifts in alliances and subversive support in the Horn of Africa suggest that regional security is intimately linked to the survival and interests of regimes in place as well as of rebel movements, which actually all gain from conflict and are respectively a part and manifestation of the problem rather than part of the solution.[61] They also suggest that ‘interactions between the states of the region support and sustain the conflicts within the states of the region in a systemic way’. [62]

It will be undoubtedly argued that the view which the author presented in this chapter is, apart from being too general and speculative, unnecessarily pessimistic and even apocalyptic. For one, the author could not bring himself to paint a rosy, ahistorical picture of the grim realities of the region. Moreover, his view arises from the sad fact that the Horn of Africa continues to face a myriad of smothering security challenges. One such challenge is the primal urge of the region’s states to secure and extend their geopolitical power in ways that are threatening to other states. The author could point to the politics during the decades preceding the conflicts in Darfur, South Sudan, Somalia and Eritrea, and even the few years preceding the 1977–1978 Ogaden war or the 1998–2000 Ethiopian-Eritrean war.

The turbulent political transitions in all of the region’s states and their reciprocal fears and disputes were so durable and interlocked that, in retrospect, the outbreak of all these conflicts seems inevitable. In fact, it should not require much analysis and imagination to understand that, in the Horn of Africa, conditions for conflict were brewing for years, if not decades and centuries. However, and paradoxically enough, it will always be difficult to weave together various contradictory trends as well as realistically assess precedents and multiple indices of a dynamic nature and of many dimensions. And, despite all the dedicated seminars, conferences, presentations, briefings, articles and voluminous books, it will always be difficult to continuously anticipate with a reasonably high degree of accuracy the different conflicts’ exact origins, scale, sustenance and implications. Furthermore, the region’s conflicts are usually continuations of previous conflicts spanning out of control and they, themselves, can very easily either set off or further complicate other conflicts.[63]

All in all, in the longer term, turmoil and conflict will continue to threaten large portions of the Horn of Africa, which is shackled to its tangled history. All of the region’s states will continue to try to survive as cohesive and united entities and to defend their territorial integrity with far greater zeal than expected. But, they will still be unable to control unregulated population movements both within and across unresolved borders and to militarily overcome rebel movements once and for all. Making matters worse, the states in the Horn of Africa will continue to be engaged in a cut-throat geopolitical chess game across the region, with leaders unable to fully get into the minds of their counterparts as well as professionally assess their real intentions, while precipitously trying to keep one step ahead of one another in order to avoid being eclipsed. The author would like to emphasise in the strongest possible way and for whoever is interested in the security of the entire Horn of Africa that the coming four years will define the region’s geopolitical map for the following twenty or thirty years.

Finally, to the question of whether the Horn of Africa forms, in Buzan’s terminology, a security complex, given all the factors mentioned in this chapter, the answer is a definite yes. In fact, the conceptual framework advanced by Buzan fits the Horn of Africa like a glove. Healy accurately noted: [64]

[H]istorical patterns of amity and enmity are deeply etched in the region. Conflicts typically stem from factors indigenous to the region, the most enduring being centre-periphery relations in Ethiopia and Sudan. There is also a tradition of outside powers making alignments with states within the regional security complex.

Nonetheless, the author will leave the readers of this chapter to judge whether this last answer by proxy holds or not.

Notes

[1] It would be difficult to reveal the names and positions of these individuals who, nonetheless, provided vital pieces of information that were integrated in the chapter.

[2] R Väyrynen, Regional conflict formations: an intractable problem of international relations, Journal of Peace Research 21(4) (1984).

[3] Buzan posits ‘the existence of regional subsystems as objects of security analysis and offers an analytical framework for dealing with those systems’ (B Buzan, O Wæver and J de Wilde, Security: a new framework for analysis, Boulder: Lynne Rienner, 1998, 11). His contribution to international relations theory was mostly to draw ‘attention away from the extremes of national and global security and focus it on the region, where these two extremes interplay and where most of the action occurs’ (Buzan, Wæver and De Wilde, Security: a new framework for analysis 14–15).

[4] M Ayoob, The Third World security predicament: state making, regional conflict and the international system, Boulder: Lynne Rienner, 1995, 58.

[5] Security refers to a weakly conceptualised but politically loaded concept that provides ‘in itself, a more versatile, penetrating and useful way to approach the study of international relations than either power or peace’ (B Buzan, People, states and fear: an agenda for international security studies in the post-Cold War era, London: Harvester Wheatsheaf, 1991, 3). Generally, it designates the condition, relative and never absolute, under which the state, the principal referent object, strives to safeguard its basic interests and organisational stability from internal vulnerabilities and mostly from external threats in an inescapably competitive international environment where states cannot ignore each other (Buzan, People, states and fear, 22–23).

Moreover, security is ‘what actors make of it, and it is for the analyst to map these practices’ (B Buzan and O Wæver, Regions and powers: the structure of international security, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003, 48).

[6] Buzan, People, states and fear , 188.

[7] Buzan, People, states and fear , 190.

[8] Ibid.

[9] M Sheehan, International security: an analytical survey, Boulder: Lynne Rienner, 2005, 49–50.

[10] T Farer, War clouds on the Horn of Africa: the widening storm, New York: Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, 1979, 1; S Danfulani, Regional security and conflict resolution in the Horn of Africa: Somalian reconstruction after the Cold War, International Studies 36(1) (1999), 37.

[11] This is one reason why Uganda is included in many of the statistics in this chapter.

[12] It is difficult to determine the accuracy of these figures, and many observers would say that Ethiopia is evenly divided between Christians and Muslims.

[13] UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA). Horn of Africa crisis report December 2008. A report to the Regional Humanitarian Partnership Team, 2008.

[14] D Shinn, Horn of Africa: priorities and recommendations. Testimony to the Subcommittee on State and Foreign Operations, Washington DC, 2009, 1.

[15] OCHA, Horn of Africa crisis report, 2008.

[16] Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre, Sudan: rising inter-tribal violence in the south and renewed clashes in Darfur cause new waves of displacement, 27 May 2010, http://www.internal-displacement.org/8025708F004BE3B1/(httpInfoFiles)/15228A399B07BA67C12577300034B9AC/$file/sudan_overview_may2010.pdf (accessed 31 June 2010).

[17] International Institute for Strategic Studies, Military balance 1972–1973, London: International Institute for Strategic Studies, 1972.

[18] International Institute for Strategic Studies, Military balance 1989–1990, London: Brassey’s, 1989.

[19] International Institute for Strategic Studies, Military balance 2007–2008, London: International Institute for Strategic Studies, 2007.

[20] Getachew Mequanent, Human security and regional planning in the Horn of Africa, Human Security Journal l(7) (2008).

[21] M Chege, Conflict in the Horn of Africa, in E Hansen (ed), Africa: perspectives on peace and development, London: Zed Books, 1987, 88; Ayoob, The Third World security predicament, 137.

[22] P Woodward, The Horn of Africa: politics and international relations, London: Tauris Academic Studies, 1996, 14.

[23] T Medhane, New security frontiers in the Horn of Africa, Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung Dialogue on Globalisation, 2004, 7.

[24] M Rupiya, Interrelated security challenges of Kenya and Uganda in eastern and Horn of Africa. Paper presented at the Conference on the Prevailing Interlocked Peace and Security Conundrum in the Horn of Africa, Addis Ababa, 2008, 14.

[25] S Wasara, Conflict and state security in the Horn of Africa: militarisation of civilian groups, African Journal of Political Science 7(2) (2002), 39.

[26] Medhane, New security frontiers in the Horn of Africa, 7.

[27] P McGowan, African military coups 1956–2001: frequency, trends and distribution, Journal of Modern African Studies 41(3) (2003).

[28] Woodward, The Horn of Africa, 118.

[29] A Swain, Ethiopia, the Sudan and Egypt: the Nile River dispute, Journal of Modern African Studies 35(4) (1997); T Debay, The Nile: is it a curse or blessing? Institute for Security Studies Paper 174, 2008.

[30] Abdel Monem Said Aly, From geopolitics to geo-economics: Egyptian national security perceptions, in National threat perceptions in the Middle East, Geneva: United Nations Institute for Disarmament Research, 1995, 19.

[31] M Heikal, Egyptian foreign policy, Foreign Affairs 56(4) (1978), 715.

[32] Swain, Ethiopia, the Sudan and Egypt: the Nile River dispute, 685.

[33] Abdel, From geopolitics to geo-economics, 19–20.

[34] J Lefebvre, Middle East conflicts and middle level power intervention in the Horn of Africa, Middle East Journal 50(3) (1996), 402; Buzan and Wæver, Regions and powers, 243.

[35] J Markakis, Introduction, in J Markakis (ed), Conflict and the decline of pastoralism in the Horn of Africa, The Hague: Institute of Social Studies, 1993.

[36] S Wasara, Conflict and state security in the Horn of Africa: militarization of civilian groups, African Journal of Political Science 7(2) (2002).

[37] L Cliffe, Regional dimensions of conflict in the Horn of Africa, Third World Quarterly 29(1) (1999), 90; S Healy, Lost opportunities in the Horn of Africa: how conflicts connect and peace agreements unravel, Chatham House Horn of Africa Group Report, 2008, 39.

[38] A Weber, Will the phoenix rise again? Commitment or containment in the Horn of Africa. Paper presented at the Fourth Expert Meeting on Regional Security Policy at the Greater Horn of Africa, Cairo, 2008, 11; S Healy, Ethiopia-Eritrea dispute and the Somali conflict. Paper presented at the Conference on the Prevailing Interlocked Peace and Security Conundrum in the Horn of Africa, Addis Ababa, 2008, 10.

[39] Woodward, The Horn of Africa, 119; M Ottaway, J Herbst and G Mills, Africa’s big states: toward a new realism, Carnegie Endowment for International Peace Policy Outlook, 2004, 1.

[40] A de Waal, Sudan: international dimensions to the state and its crisis, Crisis States Research Centre Occasional Paper 3, 2007, 10.

[41] Healy, Lost opportunities in the Horn of Africa, 39.

[42] Lefebvre, Middle East conflicts and middle level power intervention in the Horn of Africa, 397.

[43] Cliffe, Regional dimensions of conflict in the Horn of Africa, 97–99; Lefebvre, Middle East conflicts and middle level power intervention in the Horn of Africa, 401; Woodward, Th e Horn of Africa, 49.

[44] Eritrea’s top foreign-policy objective is to undermine the security of Ethiopia and create political and strategic discomfort for it in its various and delicate balancing acts in the Horn of Africa. In 1999, Eritrea opened a second front in Somalia by supporting rival proxies, with all neighbouring states feeling the fallout, and states such as Egypt and Yemen adding to the generous supply of weapons. Anything that Ethiopia supports, Eritrea goes determinedly against – Ethiopia’s support for Somalia’s Transitional Federal Government and Eritrea’s support for the Union of Islamic Courts and then al-Shabaab being cases in point. Eritrea provides training and weapons to the Somali movements with the objectives of using them as baits to entice Ethiopia and then outflank it, making Ethiopia ‘pay the price’, and also making Somalia a second front against it. Eritrea has also been supplying weapons and giving training to Ethiopian rebel movements, including the Ogaden National Liberation Front and the Oromo Liberation Front to put additional pressure on Ethiopia, which backs the Eritrean Democratic Alliance, an umbrella organisation of groups opposed to the current Eritrean regime.

[45] Buzan, People, states and fear, 189.

[46] Healy, Lost opportunities in the Horn of Africa, 39.

[47] Cliffe, Regional dimensions of conflict in the Horn of Africa, 102.

[48] Z Imru, The Horn of Africa: a strategic survey, Washington DC: International Security Council, 1989, 38–40; H Seifudin, Systemic factors and the conflicts in the Horn of Africa 1961–1991, in K Fukui, E Kurimoto and M Shigeta (eds), Papers of the 13th International Conference of Ethiopian Studies, Kyoto: Shokado, 1997, 114; Lefebvre, Middle East conflicts and middle level power intervention in the Horn of Africa, 397.

[49] M Venkataraman, Eritrea’s relations with the Sudan since 1991, Ethiopian Journal of the Social Sciences and Humanities 3(2) (2005), 73.

[50] J Young, Sudanese-Ethiopian relations in the post-Cold War era, unpublished study, n.d.

[51] Imru, The Horn of Africa, 38–40.

[52] C Legum, The Red Sea and the Horn of Africa in international perspective, in W Dowdy and R Trood (eds), The Indian Ocean: perspectives on a strategic arena, Durham: Duke University Press, 1985, 193; Lefebvre, Middle East conflicts and middle level power intervention in the Horn of Africa, 388.

[53] J Abbink, Ethiopia-Eritrea: proxy wars and prospects for peace in the Horn of Africa, Journal of Contemporary African Studies 21(3) (2003), 407.

[54] Imru, The Horn of Africa, 57.

[55] Farer, War clouds on the Horn of Africa, 114–115.

[56] A Usama, Security across the Somalia-Lamu interface, Chonjo 6 (2009), 25–26.

[57] Healy, Lost opportunities in the Horn of Africa, 44–45.

[58] Shinn, Horn of Africa, 1.

[59] Healy, Lost opportunities in the Horn of Africa, 40.

[60] Cliffe, Regional dimensions of conflict in the Horn of Africa, 108.

[61] Ibid.; Chege, Conflict in the Horn of Africa, 99.

[62] Healy, Lost opportunities in the Horn of Africa, 44.

[63] S Joireman, Secession and its aftermath: Eritrea, in U Schneckener and S Wolff (eds), Managing and settling ethnic conflicts, New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2004, 186.

[64] Healy, Lost opportunities in the Horn of Africa, 40.

References

Abbink, J. Ethiopia-Eritrea: proxy wars and prospects for peace in the Horn of Africa. Journal of Contemporary African Studies 21(3) (2003).

Abdel Monem Said Aly. From geopolitics to geo-economics: Egyptian national security perceptions. In National threat perceptions in the Middle East . Geneva: United Nations Institute for Disarmament Research, 1995.

Ayoob, M. The Third World security predicament: state making, regional conflict and the international system. Boulder: Lynne Rienner, 1995.

Buzan, B. People, states and fear: an agenda for international security studies in the post-Cold War era. London: Harvester Wheatsheaf, 1991.

Buzan, B, Wæver, O and De Wilde, J. Security: a new framework for analysis. Boulder: Lynne Rienner, 1998.

Buzan, B and Wæver, O. Regions and powers: the structure of international security. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003.

Chege, M. Conflict in the Horn of Africa. In E Hansen (ed), Africa: perspectives on peace and development. London: Zed Books, 1987.

Cliffe, L. Regional dimensions of conflict in the Horn of Africa. Third World Quarterly 29(1) (1999).

Danfulani, S. Regional security and conflict resolution in the Horn of Africa: Somalian reconstruction after the Cold War. International Studies 36(1) (1999).

Debay T. The Nile: is it a curse or blessing? Institute for Security Studies Paper No. 174, 2008.

De Waal. Sudan: international dimensions to the state and its crisis. Crisis States Research Centre Occasional Paper 3, 2007.

Farer, T. War clouds on the Horn of Africa: the widening storm. New York: Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, 1979.

Getachew Mequanent. Human security and regional planning in the Horn of Africa. Human Security Journal 7 (2008).

Healy, S. Lost opportunities in the Horn of Africa: how conflicts connect and peace agreements unravel. Chatham House Horn of Africa Group Report, 2008.

Healy, S. Ethiopia-Eritrea dispute and the Somali conflict. Paper presented at the Conference on the Prevailing Interlocked Peace and Security Conundrum in the Horn of Africa. Addis Ababa, 2008.

Heikal, M. Egyptian foreign policy. Foreign Affairs 56(4) (1978).

Imru, Z. The Horn of Africa: a strategic survey. Washington DC: International Security Council, 1989.

Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre. Sudan: rising inter-tribal violence in the south and renewed clashes in Darfur cause new waves of displacement, 27 May 2010, http://www.internaldisplacement.org/8025708F004BE3B1/(httpInfoFiles)/15228 A399B07BA67C12577300034 B9AC/$file/sudan_overview_may2010.pdf. (Accessed 31 June 2010).

IISS (International Institute for Strategic Studies). The military balance 1972–1973. London: International Institute for Strategic Studies, 1972.

IISS. The military balance 1989–1990. London: Brassey’s, 1989.

IISS. The military balance 2007–2008. London: International Institute for Strategic Studies, 2007.

Joireman, S. Secession and its aftermath: Eritrea. In U Schneckener and S Wolff (eds), Managing and settling ethnic conflicts. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2004.

Lefebvre, J. Middle East conflicts and middle level power intervention in the Horn of Africa. Middle East Journal 50(3) (1996).

Legum, C. The Red Sea and the Horn of Africa in international perspective. In W Dowdy and R Trood (eds), The Indian Ocean: perspectives on a strategic arena. Durham: Duke University Press, 1985.

Markakis, J. Introduction. In J Markakis (ed), Conflict and the decline of pastoralism in the Horn of Africa. The Hague: Institute of Social Studies, 1993.

McGowan, P. African military coups 1956–2001: frequency, trends and distribution. Journal of Modern African Studies 41(3) (2003).

Medhane, T. New Security Frontiers in the Horn of Africa. Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung Dialogue on Globalization, 2004.

Ottaway, M, Herbst, J and Mills, G. Africa’s big states: toward a new realism. Carnegie Endowment for International Peace Policy Outlook, 2004.

Rupiya, M. Interrelated security challenges of Kenya and Uganda in eastern and Horn of Africa. Paper presented at the Conference on the Prevailing Interlocked Peace and Security Conundrum in the Horn of Africa, Addis Ababa, 2008.

Seifudin, H. Systemic factors and the conflicts in the Horn of Africa 1961–1991. In K Fukui, E Kurimoto and M Shigeta (eds), Papers of the 13th International Conference of Ethiopian Studies vol. 2. Kyoto: Shokado, 1997.

Sheehan, M. International security: an analytical survey. Boulder: Lynne Rienner, 2005.

Shinn, D. Horn of Africa: priorities and recommendations. Testimony to the Subcommittee on State and Foreign Operations, Washington DC, 2009.

Swain, A. Ethiopia, the Sudan and Egypt: the Nile River dispute. Journal of Modern African Studies 35(4) (1997).

UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA). Horn of Africa crisis report December 2008. A report to the Regional Humanitarian Partnership Team, 2008.

Usama A. Security across the Somalia-Lamu interface. Chonjo 6 (2009).

Väyrynen, R. Regional conflict formations: an intractable problem of international relations. Journal of Peace Research 21(4) (1984).

Venkataraman, M. Eritrea’s relations with the Sudan since 1991. Ethiopian Journal of the Social Sciences and Humanities 3(2) (2005).

Wasara, S. Conflict and state security in the Horn of Africa: militarization of civilian groups. African Journal of Political Science 7(2) (2002).

Weber, A. Will the phoenix rise again? Commitment or containment in the Horn of Africa. Paper presented at the Fourth Expert Meeting on Regional Security Policy at the Greater Horn of Africa. Cairo, 2008.

Woodward, P. The Horn of Africa: politics and international relations. London: Tauris Academic Studies, 1996.

.jpg)