The Future of Intrastate Conflict in Africa - More Violence or Greater Peace?

20 Sep 2013

By Julia Schünemann, Jakkie Cilliers for Institute for Security Studies (ISS)

Introduction

Many African countries experienced violent transitions after independence, which included civil wars and mass killings. This is not surprising considering the divisiveness of the original boundary-making processes, the coercive nature of colonial rule and the messy process of independence. Created in haste, postcolonial states often exhibited the same characteristics as their colonial antecedents. In some instances, these problems were compounded by non-inclusive political settlements, governance failures and natural catastrophe.

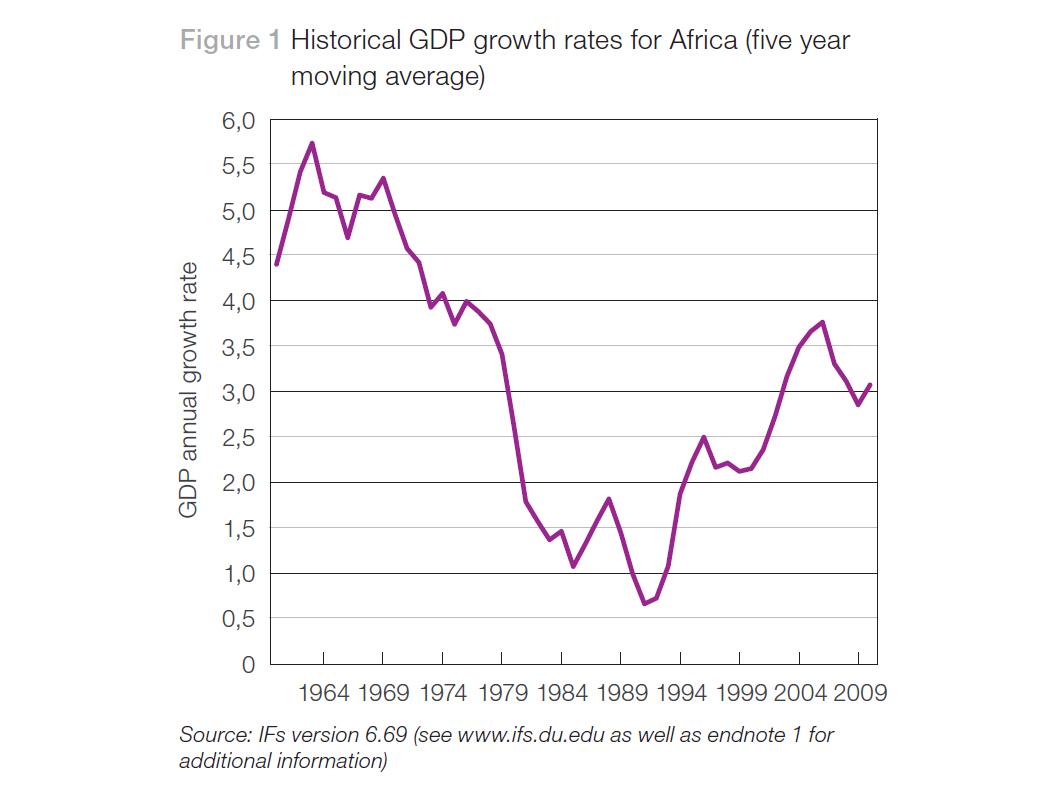

Generally, the newly independent African nations had to find their way in a bipolar world order that provided limited alternative policy choices beyond those linked to the West or members of the opposing Warsaw Pact. A number of African countries experienced initial rapid economic growth after independence and then underwent a period of general decline and decay, as living standards dropped and poverty levels increased. Although average annual gross domestic product (GDP) growth rates remained slightly positive (see Figure 1), they fell far short of the 6–7 per cent generally required to reduce poverty in a rapidly increasing population. The GDP growth rates fell to historical low levels during the late 1970s, only recovering two decades later.

Following this period of stagnation, excitement about Africa’s economic growth prospects has reached fever pitch early in the 21st century. Today many African countries present an optimistic economic outlook that contrasts strongly with the previous characterisation of Africa as a region beset by chronic instability, poverty and marginal importance to the global economy.

Recent publications by the African Futures Project, using the International Futures (IFs) forecasting system, have explored the gains in human development that are becoming possible and the potential for positive changes to the development trajectory of Africa. external page[1]call_made These include benefits from investments in education, water and provision of sanitation; the potential for a green revolution in Africa; and gains to be realised from the eradication of malaria. Collectively, these changes present the potential for greater life expectancy, better education and higher income in most countries. A number of factors provide the basis for continued positive change in Africa in the 21st century. Examples are the growth of South–South trade, particularly with China; improvements in the capacity of African governments and progress with the conflict-management capabilities of regional organisations, such as the African Union (AU); and the steady increase in the number of democracies. external page[2]call_made

In addition to these positive developments, the number of violent conflict-related deaths has been declining steadily over several decades. This decline has preceded and perhaps allowed for the more recent upturns in Africa’s development prospects. A reduction in a country’s incidence of armed violence corresponds with improved development outcomes.external page[3]call_made This trend started shortly after the end of the Cold War, although there has been an uptick in global instability in the last two to three years. external page[4]call_made

Rapid economic growth and improvements in most human development indices are expected to continue and go hand in hand with further declining levels of armed conflict in Africa.external page[5]call_made However, as argued below, it is also expected that instability and violence will persist and even increase in some instances – reflecting the changing nature of armed conflict in Africa and new dynamics that appear to supersede those of the Cold War period.

This paper describes emerging trends and patterns of conflict and instability in Africa since the end of the Cold War. It also discusses seven key correlations associated with intrastate violence on the continent and presents a number of reasons for the changing outlook regarding conflict. These reasons include increased international engagement in peacekeeping, improved regional capacity for conflict management, and Africa’s continued growth and positive prospects for development.

Africa has always been deeply affected by external influences, from the days of slavery to the present-day scramble for the continent’s resources and even its consumer market. Therefore, this paper also explores how emerging multipolarity may impact on stability. In conclusion, the IFs model is used to forecast trends of intrastate conflict.

Armed violence in Africa: trends and patterns

Civil or internal wars remain the dominant form of conflict in Africa. However, the number of wars has halved since the 1990s and the nature of the conflicts has changed significantly with the lines between criminal and political violence becoming increasingly blurred. As the World Development Report 2011 states, ‘the remaining forms of conflict and violence do not fit neatly either into “war” or “peace”, or into “criminal violence” or “political violence”’.external page[6]call_made The 2011 Global Burden of Armed Violence, therefore, challenges compartmentalised approaches to armed violence. It provides a global overview of different forms of violence, tries to understand how violence manifests in various contexts and how forms of violence interact with one another. external page[7]call_made Scott Straus provides the following crisp summary on the changing nature of conflict: ‘Today’s wars are typically fought on the peripheries of states, and insurgents tend to be militarily weak and factionalised.’external page[8]call_made

The latter part of the Cold War was a particularly violent period characterised by protracted proxy wars fought by protagonists in Southern Africa, the Horn of Africa and South-East Asia over several decades. According to both the Uppsala Conflict Data Program (UCDP)external page[9]call_made and the Heidelberg Conflict Barometer, external page[10]call_made there were steady increases in the number of armed-conflict incidents, casualties and civilians affected during this period.

After the collapse of the Berlin Wall in 1989, some previously frozen conflicts in Africa reignited violently, including those in Liberia, Sierra Leone, Rwanda and the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC). After this pent-up conflict pressure was released, a steady decline ensued. In a number of instances, insurgencies that had been externally funded before, and therefore had benefitted financially from the Cold War, turned inward for resources. They used diamonds (UNITA and the RUF in Angola), coltan (various factions in the eastern DRC), coffee and cacao (in Côte d’Ivoire), and even charcoal (in Somalia) as alternative sources of revenue. Generally, these ‘resource-based insurgencies’ external page[11]call_made were unable to grow into large-scale fighting forces and lacked the strength to challenge the dominant party in the capital. However, there have been exceptions in recent months, such as the extreme cases of Mali and the Central African Republic (CAR), where the weakening of the armed forces was significant.

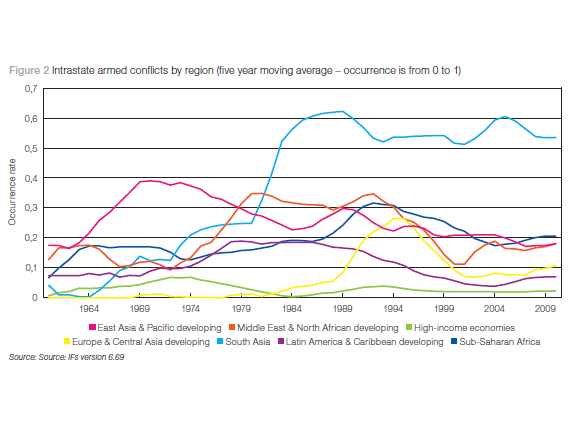

Figure 2 graphs the number of internal wars by region (as defined by the World Bank), using data from the Political Instability Task Force. external page[12]call_made Taking into consideration the increase in the number of countries – from 55 in 1946 to 179 in 1992 (the year the wars peaked) – the probability of a country being in conflict is now similar to that at the end of the 1950s and (after substantial peaks) lower than during the Cold War. external page[13]call_made

Today conflict in Africa appears to be increasingly fragmented and the number of actors, particularly non-state factions, involved in conflicts is rising. external page[14]call_made This is evident in regions such as Darfur, in Sudan, where the peace process that was finalised at the All Darfur Stakeholders’ Conference in May 2011 (in Doha, Qatar) was significantly complicated by divisions among various rebel factions. More recently, the Séléka coalition in the CAR (whose advance on the capital, Bangui, was temporarily halted by the intervention of other African countries) eventually consisted of five separate groupings. Three of these signed a peace agreement with President François Bozizé on 13 January 2013. Bozizé was eventually ousted when the coalition resumed their advance a few months later.

In the armed conflict in northern Mali, previous allies, Tuareg and Islamist rebels, fought each other in the latter stages of Operation Serval in January 2013 when French forces recaptured Mali’s north. Also, in the eastern provinces of the DRC, the M23 rebel movement has recently split into different factions ahead of the decision to deploy a neutral intervention force as part of the United Nations Organisation Stabilisation Mission in the DRC.

Therefore, scholars recognise ‘the reality of a messy empirical record in which non-state groups are frequently racked by internal differences and struggles’,external page[15]call_made which complicates the picture of state versus non-state actors.

In addition, several of today’s insurgent groups have strong transnational characteristics and move relatively easily across borders and between states. However, few present a significant military threat to governments or are in a position to seize and hold large strips of territory. Some fight on the periphery of fairly well-consolidated states, as in Senegal, Mali and Uganda, whereas others exploit the weak central authority of countries such as the DRC and Sudan.external page[16]call_made Another well-known example is al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb, which originally fought to overthrow the Algerian government while consolidating its activities across the Sahel region, particularly in northern Mali.

A number of recent publications by the Institute for Security Studies (ISS) indicate the tendency towards convergence and connection between networks of organised crime as well as their illicit activities, including money laundering, kidnapping, drug trafficking, terrorism, etc. external page[17]call_made

Violence directly associated with elections has increased in line with the rise in political contestation external page[18]call_made before, during and after polls. This is particularly common in settings where democracy has not been entrenched, such as during the elections in Zimbabwe in 2005, or where the government has been actively factional in benefitting one ethnic group above others. In Kenya, in December 2007, this culminated in post-election violence – a fate avoided during the more recent elections in 2013. In Zimbabwe’s 2008 presidential elections, more than 200 people died, at least 10 000 were injured and tens of thousands were internally displaced due to election-related violence. Other elections that were accompanied by varying levels of violence include those in Nigeria (2011) and Côte d’Ivoire (2011). In general, the push for multi-party elections in the 1990s led to an increase of associated violence across much of Africa – a pattern that has been sustained over time. external page[19]call_made

To some extent, the era of democracy and elections has seen violent competition move from armed opposition in marginal rural areas to violence around the election process itself. In this regard, Straus points out:

The onset of multi-party elections meant that, from a would-be insurgent’s point of view, governments were at least nominally vulnerable outside the context of armed resistance. Moreover, the weight of international funding flowed toward sponsoring elections and civil society organizations. For talented opposition figures, the opening of the political arena – combined with the change in international funding streams – created a strong pull away from the battlefield toward the domestic political arena. external page[20]call_made

As democracy continues to deepen and spread in Africa, in the aftermath of the so-called Arab Spring, election processes can turn violent in contexts characterised by latent conflict and tensions surrounding political competition and power-sharing arrangements. In post-conflict situations, elections are crucial for deciding who will control state institutions, and may either affirm existing patterns of power or bring in new elites, thereby transforming state–society relations.external page[21]call_made On this subject, Bekoe illuminates the fact that electoral violence seems to be related to more widespread systemic grievances and tensions, including land rights, employment and ethnic marginalisation.external page[22]call_made More systematic research is needed to explore these issues as well as the role of external stakeholders in electoral processes and their potential contribution to building resilient and legitimate states. Sisk asserts that the way in which elections are conducted is critical. He argues that sequencing, design and the extent of international monitoring of elections are the key variables that determine whether electoral processes contribute to capable, responsive states or reinforce captured, fragmented and weak states. external page[23]call_made

Localised violence over access to livelihood resources, such as land and water, is also on the increase and this includes farmer–herder conflicts. external page[24]call_made There is evidence that resource competition at community level is relatively prone to violence. external page[25]call_made In 2010 and 2011, conflicts over resources accounted for approximately 35 per cent of all conflicts in sub-Saharan Africa and 50 per cent of conflicts in the Americas. On the other hand, only 10 per cent of all conflicts in Europe, the Middle East and Maghreb, and Asia and Oceania featured resources as a conflict item. external page[26]call_made In cases of resource conflict, the possession of natural resources and/or raw materials, and the profits derived from them were determining factors in the conflicts. Globally, in this period, almost half of the resource conflicts were violent. In contrast, only 14 per cent of the conflicts over territory or international power external page[27]call_made turned violent. The conflict item most prone to violence was secession – 73 per cent of the cases – while demands for (greater) autonomy were articulated violently in only a third of the cases recorded by the Heidelberg Conflict Barometer. external page[28]call_made

Looking ahead, climate change will inevitably affect competition over livelihood resources, and will act as an accelerator and, in extreme events, a direct cause of violence and instability. Climate changes influence both crop and livestock farming, and can be crucial to food production. According to the World Development Report 2011 the occurrence of a civil conflict in sub-Saharan Africa is more likely after years of poor rainfall, reflecting the impact of one type of income shock on stability.external page[29]call_made The rate of change in climate extremes is now increasing significantly faster than in previous generations, with the result that extreme events, such as drought and flooding, are more common than in the past.

According to the World Meteorological Organization, the decade from 2001 to 2010 was the warmest since records were first kept in 1850. Global land- and sea-surface temperatures were estimated at 0,46°C above the long-term average (1961–1990) of 14°C. external page[30]call_made The results of a new study supported by the world’s largest climate modelling system show that global temperatures may warm by 3°C by 2050, taking into consideration the current rates of global greenhouse gas emissions.external page[31]call_made Many plant species, animals and even large human settlements will struggle to adapt to the current speed of climate change. This may lead to widespread displacement of people, increased conflict and suffering, particularly in countries and regions with limited adaptive capacity and resources. In 2009 various papers presented at an Oxford University conference, ‘4 Degrees and Beyond’, forecast a collapse of the agricultural system in sub-Saharan Africa in such a scenario. external page[32]call_made

In addition, there is an ongoing debate on the potential of competition over scarce natural resources (particularly food, water, energy and rare earth metalsexternal page[33]call_made) to become a major source of future interstate, regional and even international conflict. Defence industry researchers have been particularly vocal about the ‘resource wars of the future’, as have respected think tanks such as the Royal Institute for International Affairs. external page[34]call_made As populations grow, competition for food, water and energy inevitably increases. However, the projected transition from conflict over livelihoods to major interstate war over control of scarce resources remains untested. The most recent global trends report published by the National Intelligence Council of the US, Global Trends 2030: Alternative Worlds, argues that in 20 years scarcity could be national or regional in nature, but not global, although the trade-offs between food, water and energy may impact upon one other. The report argues that fragile states in Africa and the Middle East are most at risk for food and water shortages, but China and India are also vulnerable.external page[35]call_made

The Global Trends 2030 report goes on to state that, by 2030, the world will require 35 per cent more food, 40 per cent more water and 50 per cent more energy to cater for a global population of around 8,3 billion people (approximately 1,2 billion more than the present population). external page[36]call_made By that point, the process of global warming will already have had a measurable and durable impact on livelihoods across many communities, most affecting those with the least ability to adapt. Extreme heat, especially if accompanied by drought, may reduce or destroy agricultural yields. This is particularly relevant in Africa, with its rapid population growth and violent local clashes over grazing land, water, minerals and other scarce commodities and resources. Therefore, the longer-term prognosis (beyond 2030) of human-induced climate change is uncertain.

In summary, the ongoing violent intrastate conflicts in Africa tend to be on a smaller scale than in previous decades, feature factionalised and divided armed insurgents, and occur on the periphery of states. These conflicts are difficult to end because of the mobile, factionalised nature of the various armed groups; the strong cross-border dimensions; and the ability of insurgents to draw funding from (transnational) illicit trade, exploitation of local resources, banditry, and/or international terrorist networks rather than principally from external states. external page[37]call_made There are numerous examples for this in sub-Saharan Africa, including those in Uganda, Chad, the CAR, Ethiopia, Sudan, Mali, Niger, Senegal, Angola, Nigeria and the DRC. To some extent, it appears as though these conflicts represent a form of ‘resistance to the global liberal economy’. external page[38]call_made According to this view, conflict serves to protect the interests of those who would otherwise be dispossessed by globalisation, and to preserve the increasing influence of finance in determining the allocation of global power and resources.external page[39]call_made This matter will be discussed further in the section about future trends.

Read the full report .

external page[1]call_made The African Futures Project is a collaboration between the Pardee Center for International Futures at the University of Denver, Colorado, and the Institute for Security Studies, with its head office in South Africa (www.issafrica.org/futures). The International Futures (IFs) is a software forecasting system that represents relationships and interactions within and across key global systems for 183 countries from 2010 to 2100. IFs is an integrated assessment model, which means that it is characterised by dynamically interacting subsystems, rather than straight-line forecasts or extrapolations. These subsystems include modules on population, economics, health, education, infrastructure, agriculture, energy, environment, governance and international politics. The model has been developed and maintained by the Pardee Centre for International Futures (www.ifs.du.edu) by Prof Barry B Hughes. In this paper, version 6.69 has been used for all data, analysis and forecasts where the source is not indicated otherwise.

external page[2]call_made Many of these developments have recently been captured in the 2013 Human Development Report. United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), Human Development Report 2013: The rise of the South: human progress in a diverse world, 2013, http://hdr.undp.org/en/media/HDR_2013_EN_complete.pdf (accessed 12 April 2013).

external page[3]call_made Geneva Declaration Secretariat, Global burden of armed violence 2011: lethal encounters, executive summary, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2011, 10.

external page[4]call_made Heidelberg Institute for International Conflict Research (HIIK), Heidelberg Conflict Barometer 2011, http://www.hiik.de/de/konfliktbarometer/pdf/ConflictBarometer_2011.pdf (accessed 10 March 2012); and HIIK, Heidelberg Conflict Barometer 2012, http://www.hiik.de/de/konfliktbarometer/pdf/ConflictBarometer_2012.pdf (accessed 12 April 2013).

external page[5]call_made This paper defines armed conflict as a contested incompatibility between a government and an organised opposition group causing at least 25 battle-related deaths during a calendar year (see Lotta Themnér and Peter Wallensteen, Armed conflict, 1946–2010, Journal of Peace Research 48(4) (2011), 525–536).

external page[6]call_made World Bank, World Development Report 2011: Conflict, Security and Development, 2011, 2.

external page[7]call_made Geneva Declaration Secretariat, Global burden of armed violence 2011, 5f.

external page[8]call_made Scott Straus, Wars do end! Changing patterns of political violence in sub-Saharan Africa, African Affairs 111(443) (2012), 181.

external page[9]call_made Uppsala Conflict Data Program (UCDP), www.ucdp.uu.se/database (accessed 10 March 2012).

external page[10]call_made HIIK, Heidelberg Conflict Barometer 2011.

external page[11]call_made Jakkie Cilliers, Resource wars – a new type of insurgency, in Jakkie Cilliers and Christian Dietrich (eds), Angola’s war economy, Peace, profit or plunder? Pretoria: Institute for Security Studies, 2000.

external page[12]call_made See http://globalpolicy.gmu.edu/political-instability-task-force-home/.

external page[13]call_made Erik Melander, Magnus Öberg and Jonathan Hall, The ‘new wars’ debate revisited: an empirical evaluation of the atrociousness of ‘new wars’, Uppsala Peace Research Paper 9, http://www.pcr.uu.se/digitalAssets/18/18585_UPRP_No_9.pdf (accessed 22 February 2013). The authors quote the work of Nils Petter Gleditsch, Peter Wallensteen, Mikael Eriksson, Margareta Sollenberg and Håvard Strand, Armed conflict 1946–2001: A new dataset, Journal of Peace Research 39(5) (2002), 621.

external page[14]call_made The UCDP tabulates the number of actors involved in conflicts and refers to dyads, defined as a pair of warring parties. In interstate conflicts, these warring parties are governments of states, whereas in intrastate conflicts, one is the government of a state and the other is a rebel group. See http://www.pcr.uu.se/digitalAssets/124/124259_conflicts_dyads_2011.pdf (accessed 15 March 2013). For evidence on the increased fragmentation of conflict, see also Themnér and Wallensteen, Armed conflict, 1946–2011, 566.

external page[15]call_made W. Pearlman and K.G. Cunningham, Nonstate actors, fragmentation, and conflict processes, Journal of Conflict Resolution 56(1), 4; Straus, Wars do end!, 181.

external page[16]call_made Straus, Wars do end!, 181–182; I. Salehan, Rebels without borders: transnational insurgencies in world politics, New York: Cornell University Press, 2009.

external page[17]call_made Tuesday Reitano and Mark Shaw, Check your blind spot – confronting criminal spoilers in the Sahel, Institute for Security Studies, Policy Brief, 2013; Lori-Anne Théroux-Bénoni, Mali in the aftermath of the French military operation, Institute for Security Studies, Situation Report, 2013; Mark Shaw and Tuesday Reitano, The evolution of organised crime in Africa: towards a new response, Institute for Security Studies, Paper 244 (April 2013). All available at www.issafrica.org.

external page[18]call_made Straus, Wars do end!, 192–193.

external page[19]call_made Ibid.

external page[20]call_made Straus, Wars do end!, 197.

external page[21]call_made Timothy Sisk, Pathways of the political, in Roland Paris and Timothy Sisk (eds), The dilemmas of statebuilding: confronting the contradictions of postwar peace operations, New York: Routledge, 2008, 196–224.

external page[22]call_made Dorina Bekoe, Trends in electoral violence in sub-Saharan Africa, United States Institute of Peace (USIP) Peace Brief, 2010, 13.

external page[23]call_made Sisk, Pathways of the political, 2008.

external page[24]call_made Straus, Wars do end!, 179, 193.

external page[25]call_made HIIK, Heidelberg Conflict Barometer 2011, 4.

external page[26]call_made The Heidelberg Conflict Barometer defines conflict items as follows: ‘Conflict items are material or immaterial goods pursued by conflict actors via conflict measures. Due to the character of conflict measures, conflict items attain relevance for the society as a whole – either for coexistence within a given state or between states.’ HIIK, Heidelberg Conflict Barometer 2011, 120.

external page[27]call_made Defined as change in the power constellation in the international system or a regional system therein, especially by changing military capabilities or the political or economic influence of a state. HIIK, Heidelberg Conflict Barometer 2011, 120.

external page[28]call_made HIIK, Heidelberg Conflict Barometer 2011, 5.

external page[29]call_made World Bank, World Development Report 2011, 6.

external page[30]call_made World Meteorological Organization, A summary of current climate change findings and figures, 2013, http://www.wmo.int/pages/mediacentre/factsheet/documents/ClimateChangeInfoSheet2013-03final.pdf (accessed 7 April 2013).

external page[31]call_made Ibid.

external page[32]call_made International Climate Conference, Implications of a global climate change of 4+ degrees for people, ecosystems and the earth system, Oxford, 2009, http://www.eci.ox.ac.uk/4degrees/ (accessed 6 April 2013).

external page[33]call_made A group of 17 chemical elements widely used in advanced manufacturing.

external page[34]call_made See Bernice Lee, Felix Preston, Jaakko Kooroshy, Rob Bailey and Glada Lahn, Resource futures, London: Chatham House, Royal Institute of International Affairs, 2012, 152. The authors forecast both the increased securitisation of resource politics and the potential for militarised responses.

external page[35]call_made The National Intelligence Council (NIC), Global trends 2030: alternative worlds, 2012. Available at www.dni.gov/nic/globaltrends.

external page[36]call_made NIC, Global trends 2030, iv.

external page[37]call_made Straus, Wars do end!, 188; Melander, Öberg and Hall, The ‘new wars’ debate revisited; Lacina Bethany and Nils Petter Gleditsch, Monitoring trends in global combat: a new dataset of battle deaths, European Journal of Population, 21(2–3) (2005), 145–66.

external page[38]call_made Mark Duffield, Social reconstruction and the radicalization of development: aid as a relation of global liberal governance, Development and Change 33(5), 1049–1071, cited in Melander, Öberg and Hall, The ‘new wars’ debate revisited, 8.

external page[39]call_made Globalisation is increasingly de-Westernised as a result of the rise of the South and the deleveraging of Western influence.