Solving the EU's Southern Immigration Problems

19 Dec 2013

By Jochen Klingler for ISN

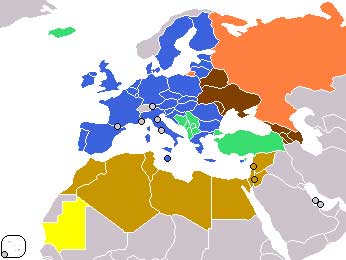

Humanitarian disasters similar to those recently witnessed off the coast of Lampedusa are by no means a rare occurrence, and may even become more frequent over the coming years. According to some external pageestimatescall_made, over 8,000 refugees have died trying to cross the Mediterranean Sea since 1990, with some Non-Governmental Organizations (NGO) claiming the true figure to be nearer to 25,000. At fault here is not a dysfunctional European Neighbourhood Policy (ENP), but the inability of states to cooperate productively to transform it into an effective political strategy to protect the European Union (EU) from illegal immigration.

A Troubled Neighborhood

Ongoing political violence and instability on the EU’s southern fringe means that it is highly likely that illegal immigration will be a major security challenge for the region for the foreseeable future. According to the “external pageAnnual Risk Analysis 2013call_made” by FRONTEX, the EU’s border control mission, ‘Syrians were the fastest growing nationality detected for illegal border-crossing between 2011 and 2012’. In 2012, Syrian nationals were also the main document fraudsters among groups responsible for illegal immigration. Italian officials in particular have been worried about a external pagesurge in arrivals of migrants from Syriacall_made. At the same time, illegal immigration through the Central Mediterranean (via Italy and Malta) surged from 1,662 in 2010 to 59,002 in 2011. Primarily responsible for this increase were nearly 28,000 detected illegal immigrants from Tunisia in 2011. The report also states that Libya increasingly serves as a hub for the departure of most sub-Saharan refugees.

The repercussions of the influx of refugees from across the Mediterranean Sea are obvious: border patrol units like the Italian Coastguards are overextended rescuing sometimes hundreds of refugees a night, as it was the case in mid-October 2013 when Italian authorities intercepted some 800 migrants. This, of course, increases the likelihood that more even more migrants will drown in the Mediterranean Sea. It also aggravates the situation in refugee camps on Lampedusa, as well as in Eritrea and Morocco. In 2011, for instance, riots broke out in a refugee camp in Lampedusa when migrants protested against inhumane living conditions after the island following the arrival of thousands of refugees escaping unrest in Tunisia and Libya. In Morocco, the representative of the United Nations High Commissioner on Refugees (UNHCR) warns that an increasing number of refugees residing in urban areas are proving to be a growing challenge for local authorities.

Innocent human beings are not the only illegal traffic trying to make its way to the Eurozone. Drug traffickers and Islamic radicals are also taking advantage of illegal immigration, as Italy’s Foreign Minister Emma Bonino told a news conference at an EU foreign ministers’ meeting in Brussels in November 2013. But why is it proving to be so difficult for the world’s richest continent to alleviate rampant illegal immigration and find an orderly and humane way of dealing with asylum seekers?

Promising Strategies - Political Inactivity

It seems that in light of the socio-political changes occurring along the EU’s southern borders, the full realization of the ENP’s core objective - to turn the European fringe into a realm of social harmony and economic stability – appears to be increasingly illusionary. Even the specialized Euro-Mediterranean Partnership (EUROMED), which seeks to foster economic integration and democracy, seems ill-equipped for dealing with the immigration problems lining up along the EUs southern borders. This is surprising given that the EU has tried to capitalize upon the strategic opportunities presented by the Arab Spring. Take, for example, the “Partnership for Democracy and Shared Prosperity”. Launched in March 2011 by the High Representative of the EU, the Partnership provides tailor-made support for those southern neighbors experiencing democratic transformation. This includes financial assistance for democratic reforms or joint operations within FRONTEX, such as Operation HERMES (2011). Accordingly, the problem does not seem to be one of strategic and conceptual gridlock or inactivity. Instead, there appears to be a lack of political will to fully translate theoretical ambitions into action, especially among European states least affected by immigration emanating from the south.

Least Affected could do More

A way to better understand this quandary might be to revisit Robert O. Keohane’s “After Hegemony”. Keohane argues that cooperation does not develop out of altruism or some international interest. Instead, states only cooperate out of discord, especially if their own security and wealth is affected. Regarding the immigration issue at the EU’s southern borders, the primarily affected states are Greece, Italy, Malta and Spain. They are currently in discourse with the departure states of migrants, for instance Libya. This is why Joseph Muscat, Prime Minister of Malta, travelled to Libya in mid-October 2013 to meet his counterpart to negotiate possible solution to the problem. This is also why Muscat calls on the EU to support its southern member-states states and, in conjunction with his Italian counterpart, demands more funds from Brussels to tackle illegal immigration.

By sharp contrast, states that have been barely affected by rampant migration from this region refuse to share the burden with their southern friends. On October 2013, for example, Sweden and Germany external pagerejected calls for the reform of Dublin IIcall_made, the EU regulation that stipulates that asylum seekers must apply for asylum in the country through which he or she entered the EU. Reforming the Dublin Regulation could significantly relieve Italy and Malta from scores of refugees and free-up much-needed funds and resources for more pressing challenges.

According to Keohane’s argument, the underlying problem here is cynicism: Germany and Sweden are not nearly as affected by this form of immigration as Malta and Italy and, therefore, only make minimal contributions, despite the fact that they have the financial strength to be more supportive. This problem has also been acknowledged by Cecilia Malmström, the EU Commissioner for Home Affairs. She argues that the burden of immigration to the southern flank of EU has so far been shouldered by only six or seven states. Instead, Germany has been more worried about the imprisonment of Julija Timoschenko and Ukraine’s association agreement with the EU than the far more pressing security challenges posed by rampant illegal immigration across the Mediterranean. The reason is simple: the successful completion of the association agreement with Ukraine would have considerably opened the country as a market for German exporters. But what immediate gains are there to make from spending money and time on illegal immigration unless immediate security risks are at stake?

Looking to the Future

It’s no secret that each and every state puts its own national interests ahead those of other countries. However, the way that the EU and its member-states conduct politics with each other is, in many ways, truly exceptional. Its success over the past 65 years has often depended on exceptional inter-state behavior where sovereign states submitted to institutional authority and acted according to a common interest. An example would be the creation of the Eurozone where the monetary policy of 17 states is managed by one institution, the European Central Bank. Such unorthodox conduct of international relations that further strengthens the EU and corroborates its cohesion for the future has to be maintained. Countries like Germany and Sweden should do considerably more than just pay lip service to the alleviation of the immigration problem in the Mediterranean Sea. The Dublin II regulation has to be reviewed in order to ease the immigration burden on countries like Italy and Malta. FRONTEX has to be considerably developed and augmented with more personnel and better equipment. Finally, the EU’s relations with states like Syria, Egypt and Libya have to be reconsidered. Consistent meddling in their domestic affairs and patronizing criticism only impedes the EU’s ability to muster constructive cooperation with these states. Instead, member-states should support existing strategies, like the abovementioned “Partnership for Democracy and Shared Prosperity”.

For additional reading on this topic please see:

Ending of Transitional Restrictions for Bulgarian and Romanian Workers

People Dying at the EU's External Borders: Can the Summit Find the Right Answer?

EU Immigration Policy: Act Now Before it is Too Late