An Interview with Charles Powell, Director of the Elcano Royal Institute

28 Feb 2014

In 2010, the Elcano Royal Institute launched the annual Elcano external pageGlobal Presence Indexcall_made. This index measures and ranks the 'external presence' of various countries. Can you tell us more about how you assess this presence? Also, what were the results of the latest ranking?

In our view, global presence refers to a country’s ability to project itself externally. It measures to what extent and in what ways countries ‘are out there’, regardless of whether they are exerting actual influence or power.

Therefore, the Elcano Global Presence Index orders, quantifies, and aggregates the ‘external projections’ of different countries in three ways – economic presence, military presence, and ‘soft presence’.

- Economic presence is measured through the flow of exports of energy products, primary goods, manufactured goods, and services, as well as through foreign direct investment.

- Military presence is measured through the troops deployed in international missions and available military equipment.

- Soft presence is measured through migration, tourism, performance in international sports competitions, the exports of audiovisual services, the projection of information on the Internet, the number of international patents registered, the articles published in scientific journals, the number of foreign students, and finally, the gross flows of development assistance

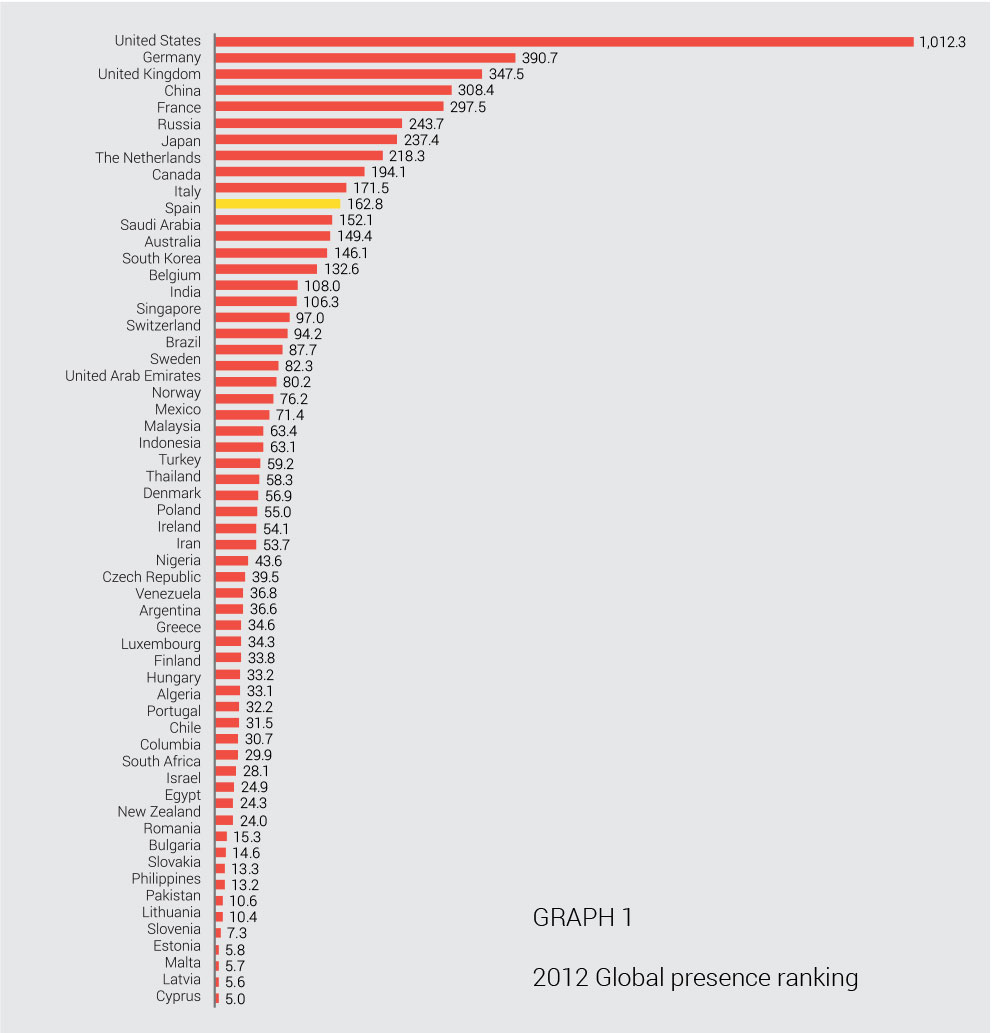

The latest ranking (see graph 1) confirms that the United States still holds the greatest global presence. Germany follows far behind in second place, and the United Kingdom is in the third position. After surpassing France, China comes in at the fourth position, thus continuing the uphill trajectory this Asian economy has experienced in the last decades. Russia also continues its steady ascent and occupies the 6th place in global presence, after passing Japan in 2012.

How has the economic crisis affected Spain’s foreign policy and 'global presence'?

Since its transition to democracy in the 1970s, Spain’s foreign policy has focused on re-establishing itself in the international community. This effort, I might add, resulted in a spectacular increase in its global presence score from 1990-2012 – i.e., it nearly quadrupled from 41.8 to 162.8. However, most recently Spain has yielded its share of presence to emerging countries such as China. For example, even though its global presence share grew from 2.1% in 1990 to 2.9% in 2010, it fell back to 2.7% in 2012, which then caused it to slip from 10th to 11th place in our most recent global presence ranking.

A second reason for the slip is that the sources of Spain’s presence may be unbalanced – i.e., it rests on 1) its soft dimension, which –in the particular case of Spain– is greatly dependent on tourism and sports instead of more strategic assets such as education and technology, and 2) a process of economic internationalization that is more dependent on foreign direct investment than on more durable exports.

Finally, the current economic crisis has contributed to Spain’s recent and relative decline in our Index. Although its annual growth between 2000 and 2010 was 11%, that number has shrunk to an annual growth rate of 6.7% in 2010-2012.

In looking at Spain’s future defence posture, a recent Elcano Policy Paper argues that traditional defense models are rapidly losing their utility. Why is that and what are the options that Spain should pursue in restructuring its military?

Traditional Western defence models are losing their utility because they no longer fit the geopolitical and geostrategic contexts that now exist, and which also remain in flux. For example, the geopolitical epicenter is shifting from the Euro-Atlantic region to Asia, major post-Cold War military operations are ending, the economic crisis is far from over, and the gap between governmental defence policies and societal strategic cultures is widening. These factors, and others, then affect when and where military force will be used, the posture and structure of the armed forces involved, the character of multilateral military organizations, the nature of the defence technological and industrial base, and much more.

Given the structural impact of these changes, we must first reassess our strategic priorities before we restructure our militaries. In the case of Spain, this means prioritizing the MENA-Sahel-Gulf of Guinea-Horn of Africa regions over all others. Second, it means moving from alliances to coalitions, from exclusive organizations to inclusive networks, and from ostensible allies to willing and able partners. Third, Spain’s armed forces must evolve and become a joint force that is able to operate together in a ‘light-footprint’ manner, and with other partners. Fourth, Spanish defence budgets must prioritize programs that are long-term, affordable, transformational and accountable. Finally, Spain must legitimate its defence model by linking its perceived utility to the daily lives of its citizens. If it fails to this, the model will naturally not be legitimate in the public’s eyes.

For additional information please see:

external pageThe coming Defence: criteria for the restructuring of Defence in Spain (Elcano Policy Paper)call_made

Emerging Spain? (Elcano Working Paper)

external pageMore Elcano Publicationscall_made

external pageElcano Blogcall_made