People Decide, Parameters Shape: US Foreign Policy under Barack Obama

4 Apr 2014

By Martin Zapfe for Center for Security Studies (CSS)

This chapter of Strategic Trends 2014 can also be accessed here.

As 2014 marks the end of the longest war in US history, it is time to look at US foreign policy beyond Afghanistan. In doing so, it is imperative to differentiate between the people who decide and the parameters that shape these decisions. Under President Barack Obama, with his domestic focus and aversion to grand strategies, the US has entered a phase of strategic pragmatism. This trend will persist, as three parameters continue to shape every President’s decisions: the aftermath of the financial crisis, a US public weary of foreign wars, and the enormous shale gas revolution.

The United States of America is still the most powerful state in the world, and will be for years to come. No other competitor comes even close in its combination of military, economic, and soft power. Yet once again we have an abundance of debate regarding an imminent decline of the US. Friends and foes alike wonder which path the US will take in the next few years under President Barack Obama, and beyond. Will it take the road of an energetic foreign policy, based on a willingness to engage and to act militarily, if necessary? Or, on the contrary, will it move towards what is often called isolationism – an effort to decouple the country from the political and military entanglements of world politics, or at least of most of it, while still trying to profit economically?

Neither of these expectations is entirely realistic. Instead, this chapter puts forward a twofold argument: First, what we are likely to see is a protracted phase of ‘strategic pragmatism’. This strategic pragmatism will likely take its most distinct form under President Barack Obama, as a result of his personality, worldview, and political priorities. Second, however, the underlying strategic drivers – most importantly, financial constraints, domestic war weariness, and the shale energy revolution – are independent of Obama and will affect US policy beyond his presidency. And it is because of these parameters that any long-term view on US foreign policy must necessarily come to the conclusion that the US will tend towards disengagement – at least from parts of the world deemed secondary.

To support this argument, the chapter is structured as follows: First, it will argue that to understand the foreign policy of the US, especially under President Obama, we have to get away from a search for strategy and instead focus on the parameters that shape essentially pragmatic decisions. Second, it will detail three of the most decisive parameters shaping today’s and tomorrow’s decisions. Third, it will look at the first six years of Barack Obama’s presidency and show how the personality of Obama significantly increased the importance of these parameters for US foreign policy during those years. Fourth, it will depict two of the most important effects of this combination of personality and parameters. These are a fundamental economization of foreign policy on the one hand, and on the other a global two-tier military posture focusing the conventional, symmetric warfare capacity on the Asia Pacific region.

People decide, parameters shape

President Obama’s foreign policy has been exhaustively described. Naturally, political analysts as well as historians tend to focus on real or perceived patterns of behaviour that can be subsumed under a ‘grand strategy’. However, real life policy decisions tend to evade those categories. This is especially true in times when and on issues where the US executive is under immense pressure to make critical decisions under considerable time pressure. Here the White House’s Situation Room is anarchic in that it more often than not defies theoretical, logical, and strategic imperatives. Rarely do policy makers decide according to what option falls into the logic of a previously-stated strategy. They tend to judge these options against various criteria – military feasibility, domestic support, the position of Congress, the likely impact on other, potentially more important developments, to name just a few. Then, within a structured and highly bureaucratized decision-making process involving numerous influential agencies, these options are narrowed down towards an approach that might appear ‘strategic’.

Yet, in the end, presidents decide. And they can do so to the surprise of outside observers, and even their closest advisors. The foremost recent example of such a development was the 2013 debates within the US administration regarding the striking of Syrian targets after the massive use of chemical weapons close to Damascus. After President Obama had publicly communicated his determination to retaliate against Syrian government targets, he reportedly surprised even his own Secretary of State John Kerry with a new focus on Syria giving up its chemical weapons, which meant he refrained from using military force. While important considerations no doubt played a role in Obama’s decision – including the parallel talks with Iran on its nuclear programme, and domestic war weariness – it was definitely not an element of a grand strategy.

Of course, if defined narrowly in terms of geography or issue, foreign policy strategies can be important. Again, there are good examples. In the 1970s, Secretary of State and National Security Advisor Henry Kissinger famously opened diplomatic channels to the People’s Republic of China within a carefully devised and consequentially implemented strategy; and under President Bill Clinton, the US committed itself, with moderate success, to the strategy of ‘dual containment’ of Iraq and Iran. In these cases, an agreed and enforced policy goal was supported by a concerted effort on the part of US governmental agencies – a narrow strategy with important benefits.

However, when it comes to ‘grand strategies’ concerning the role of the US in an (always) changing world, caution is the order of the day. If a ‘unipolar moment’ ever existed, it did so during the 1990s, during the presidencies of George H.W. Bush and Bill Clinton. With the demise of the Soviet Union, the US faced a singular moment of possibilities; international involvement had both become more feasible and gained international legitimacy. However, the Clinton administration had to abandon its first interventionist ventures after comparably light casualties in Somalia. Further military interventions were deemed impossible, and the course of the next years seemed clear. Yet, only two years after Somalia, the US intervened decisively and forcefully in the Balkan wars, thanks to President Clinton’s work against the strong scepticism of the American public, and corresponding opposition in Congress.

People decide, parameters shape – this is, in short, the essence of policy analysis and of this chapter. No political observer is able to predict any single decision of the US executive, let alone the president, with certainty. What can be analysed and predicted, however, are some of the parameters likely to shape foreign policy decisions; we may then try to factor in the personality of the president.

Shaping the Situation Room

Three main parameters have shaped President Obama’s foreign policy: first, the financial and economic crisis of 2008; second, public war weariness after the inconclusive wars in Iraq and Afghanistan; and, third, the perceived energy independence after the advent of shale gas and tight oil extraction on US soil.

Austerity and altruism – the financial crisis

Six years after the collapse of the famed Lehman Brothers, it is easy to forget the devastating consequences the financial crisis had on the US economy and the lives of US citizens. According to the US National Economic Council, the US lost an average of 800,000 jobs per month, the economy was contracting at above 8 %, and US households had lost a staggering $ 19 trillion in wealth by January 2009 – the month President Obama was inaugurated.

Governments have only a limited bandwidth to deal with policy issues. And in the short term, the financial crisis absolutely dominated the domestic political agenda of the new president, with the possible exception of health care reform. Unprecedented emergency measures were implemented to avoid a complete meltdown of the economic system. In addition, the globalized financial system meant that domestic politics spilled over into foreign policy, where concerted measures to contain and overcome the crisis dictated the agenda with the G8 (later the G20), Europe and Asia. While other foreign policy issues, such as the way ahead in Afghanistan, the drawdown in Iraq and the reset with Russia demanded attention, they essentially remained second-tier policy questions for the administration.

In the mid-term, the financial crisis receded from the immediate agenda, but it continued to shape foreign policy. A sense that “foreign policy begins at home” set in, and policy debates centred on the question of whether the defence budget should be exempted from austerity measures.

Although the question of defence spending was and remains hotly debated, the Pentagon’s budget is set to shrink dramatically by the end of this decade. The spending cuts that were announced by President Obama in January 2012 alone amount to about

$ 500 billion over five years. This reduction would have pressed the services hard and reduced manpower as well as weapon systems and deployment routines; it could, however, have been legitimately seen as effective leverage to trim the military towards more efficiency, thus not only relieving the budget pressure, but inducing military reform as well.

This cannot be said, however, of the ‘lawn mower’ of sequestration. The additional across-the-board cuts of $ 1.2 trillion over ten years will massively affect the military, crossing the threshold from mere reductions in quantity towards likely losses of quality. These reductions will hit the land forces disproportionately, but they will also reduce the effectiveness and mission-readiness of the ‘strategic services’, Air Force and Navy. As Michael Haas puts it in the preceding chapter, a security provider, like a bank, will never be able to meet all its claims simultaneously. To stay within the picture, the financial crisis has forced the US to reduce its military net equity and leverage the remaining sum – at a time of increasing global risks.

Been there, done that – war weariness in the US

As of 2014, Operation Enduring Freedom (OEF) in Afghanistan is the longest war in US history. Not surprisingly, then, a marked and deepseated war fatigue has taken hold of the US public and is now one of the major parameters in the mind of US decision-makers. According to a December 2013 study of the ‘Pew Research Center for the People & the Press’, the majority of the American public has become distrustful of foreign intervention, as 52 % of Americans believe the US should “mind its own business internationally”, a remarkable increase of 22 % compared to 2002, at the beginning of President Bush’s ‘Global War on Terror’. Concurrently, 53 % of Americans believe that the US is “less powerful today than ten years ago”, an increase of 33 % from 2004. The US population is turning inwards.

While both major US wars in Iraq (2003 – 2011) and Afghanistan (since 2001) led to severe casualties in absolute numbers (a combined number of 6795 US service members killed and countless more wounded by January 2014), they are not the primary reason for this war weariness. By historical comparison, and considering the length of the period in question, the casualties are relatively light; moreover, they were suffered by a professional, multi-tour, all-volunteer military that is increasingly separated from society at large.

What matters more is both the huge amount of resources put into the two enterprises, and the at best inconclusive result of the wars – especially when Americans themselves are feeling the impact of the financial crisis. A recent study by the Harvard Kennedy School of Governance estimates the potential overall costs (including long-term claims) of the two wars at between $ 4 – 6 trillion. As a result, military power as a means towards political ends beyond pinpoint, limited strikes has been discredited for the time being.

Thus a growing distrust towards military intervention increasingly mirrors the atmosphere of the 1990s. This explains to a degree the reluctance of the Obama administration to intervene militarily in the Syrian proxy war lest it be drawn into it – a striking parallel to its non-intervention in Rwanda in 1994. An increasing anti-interventionism will continue to hold sway and to shape any decision on foreign engagement beyond the economic and political sphere. That said, isolationist tendencies did not prevent President Clinton from intervening in Bosnia – and they might not prevent a future president from following the same path.

Shale energy – new energy for isolationism

Much has been written about how the increased production of shale gas and tight oil will significantly shape US foreign policy. However, the perceived effects will be more important than the real economic advantages, in that they significantly strengthen the war weariness detailed above without really reducing US dependency on secure trading routes, a stable Middle East and a reasonable oil price.

Views of US Global Power

Since the oil shock of the seventies, the US has dreamt the dream of energy independence. Oil dependence was regularly perceived as being chained to uncomfortable alliances and undemocratic regimes with a less-than-stellar record on human rights. Thus it is to a certain degree true that energy dependency forced the US to stay engaged in foreign affairs even at times when other, nobler, interests were not at stake. Energy dependence brought realpolitik into many policy calculations.

Shale energy will change this basic calculus, and for a long time to come. However, it is not a silver bullet on the way to energy independence. The International Energy Agency (IEA) estimates that the US may become the world’s biggest oil producer as early as 2015 – well within President Obama’s presidency – and remain in this position for at least the next decade.

However, numerous experts have pointed out that the truth is not so simple. The global nature of oil markets means that even when the US’ own exploitation is growing significantly, the country is dependent on a stable and reasonable oil price. Instability in critical supply regions will thus continue to have an impact on US interests. Since few other nations that are far more dependent on Middle Eastern oil – like China and India – seem, for the time being, willing to replace a potentially retreating US as anchor of stability in the region, the US will remain indispensable.

Taken together, the shale boom, and even more so the enthusiastic reports on the shale boom, will increase the thresholds for US intervention on the basis of economic stability. It reinforces existing trends within the population to refrain from foreign policy activism, and will therefore shape foreign policy decisions in the years ahead.

Obama as foreign policy president

While these three parameters shaped President Obama’s foreign policy, it was his personality and the definition of his office that capitalized on the parameters. Where some predecessors reverted to ideological swords to cut the Gordian Knot of world politics, Barack Obama prefers the scalpel for managing foreign policy challenges, relieving their pressure without aiming for a perfect cure – at least in the short term.

Aversion to grand strategies

Besides the simple non-existence of foreign policy grand strategies outlined above, Barack Obama does not like the notion. This is crucial to an understanding of his foreign policy. Every strategy is at the very core a simplification of reality. Real-life developments are compressed into planning parameters, thereby being simplified to the extreme.

Yet Barack Obama, the highly intelligent Harvard jurist, seems to have an inert distrust of those reductions of reality. His short-term policy choices are telling: he continued the military and intelligence element of President Bush’s security policy while discarding the ideological superstructure of democratic transformation that made it a grand strategy. Again, Obama tends to manage foreign policy, and despite his visionary appeal, he is a realistic pragmatist to the bone.

It is here that we find the biggest difference between the presidencies of President Obama and his predecessor. The last grand strategy of an US administration was, arguably, the ‘Global war on Terror’ waged by the administration of George W. Bush after the attacks of 11 September 2001 and codified primarily in the National Security Strategy of 2002. With its emphasis on the export of liberty and the democratic transformation of states and regions, coupled with intensive and worldwide military and intelligence campaigns, it is a prime example of the power of the US being mobilized towards a global goal with multiple means.

Obama’s foreign policy is a continuation of his domestic policy, and he has conducted it as he campaigned – by generating high hopes through brilliant speeches. However, with regard to actual policy developments, Obama has, in the words of Aaron Miller, focused primarily on transactional instead of transformative leadership, meaning that his White House has seemed to understand foreign policy as the management of challenges, not the fulfilment of visions laid out in speeches.

While intellectually appealing, President Obama’s pragmatic management approach to foreign policy has significantly raised strategic insecurity with traditional partners like Europe, Saudi Arabia and Israel. At the same time, it has failed to sufficiently reassure partners in Asia – traditional allies as well as those states not looking for an alliance but for a balancer to China. President Obama is in danger of harvesting the worst of both worlds. The verdict is out.

The White House centre stage

In day-to-day conduct, the White House under Obama is at the centre of every important policy decision. This highly centralized policy process is the result of two experiences: First, during his first campaign, Obama relied on a small circle of advisors not connected to democratic foreign policy circles. Those advisors followed him into the White House, while Hillary Clinton called the ignored former elite into the State Department. Thus the ‘underdog’ campaign of 2008 was continued during his presidency, with the White House taking over the role of his campaign headquarters. Second, Obama learned early that the bureaucratic decision-making process could deliver policy results markedly different from what he had ordered. While he effectively ended the war in Iraq in 2011, he at the same time escalated the Afghan war into a fullfledged counterinsurgency campaign. This strategy change, if temporary, was communicated by Obama as focusing on the core of Al-Qaida instead of on the Taliban. What he got was different – the operational template of Iraq in the villages of Afghanistan. This experience seems to have contributed to White House security circles’ marked distrust of the departments, and the highly centralized decision-making process since.

Beyond Iraq and Afghanistan, Obama’s campaign against Al-Qaida may be the most instructive with regard to the character of Obama’s presidency. He drastically stepped up direct action, mostly through drone strikes by the CIA or the military, against suspected Al-Qaida operatives and members of groups considered to be associated.

Armed drones used against individual targets constitute the optimal means for President Obama as they fulfil three criteria critical for the president. First, they are supposed to target dangerous operatives and thereby prevent catastrophic attacks on the scale of 9/11 that would inevitably shape his presidency and derail any domestic agenda. Second, they are perceived as a cost-effective alternative to a large number of ‘boots on the ground’ in the respective areas of operations, thereby fulfilling his pledge to refrain from armed nation building. And, third, the command and control process for the strikes is reportedly highly centralized, with the president and his closest advisors reserving the right to make some of the final decisions. Culminating in the commando operation that killed Osama bin Laden in Pakistan in May 2011, this effort has been so far successful, since Al-Qaida seems seriously weakened. Again, the attempt to centrally ‘manage’ and contain the terror threat became the core element of Obama’s security policy, contrasting markedly with his visionary speeches of peaceful transformation. This contrast between rhetoric and conduct was, if anything, the most striking feature of Obama’s first term in office.

If there is anything resembling a grand strategy in the Obama administration, it is the fundamental rebalancing of US resources towards the vast Pacific region, announced in 2011. In essence, the ‘Pivot to Asia’ is nothing more than the consequential next step after the end of the Cold War. Since the beginning of the 1990s, US policy-makers from both sides of the aisle have repeatedly pushed for a distancing from the old continent. With core Europe pacified, and the Russian threat drastically reduced, the US had “no dogs in the fight(s)” of this region, as famously stated by Secretary of State James Baker. President Clinton had to invest a substantial amount of political capital to bring the US to intervene in the escalating Bosnian war, showing again that it was US military capabilities and its political weight that were decisive in bringing this war to a close. The same held true four years later in Kosovo. Reluctantly, the US was willing to intervene once again, while at the same time pushing the European allies hard to improve their military capabilities. The obvious split over the war in Iraq in 2003 was, on one level, proof that a united and strong Europe was no longer one of the key interests of the US. While the tone of the George W. Bush administration was new, the relevant policy content was not.

Idealists tempered by realism?

As stated above, in the end it is people who decide. During the second Obama term, changes in key positions seem to have had decisive foreign policy implications, conveying the image of a markedly more interventionist administration tempered by a reluctant president. The profoundest consequences have been caused by the ascent of John Kerry to Secretary of State. While his predecessor Hillary Clinton, together with Assistant Secretary of State Kurt Campbell, embodied the Pivot as the main foreign policy strategy of the administration, Kerry embodies a rebounding towards the ‘traditional’ fields: Europe and, especially, the Middle East. In addition, he explicitly renounces expectations that the US itself will move towards global disengagement.

Indeed, the nuclear negotiations with Iran, the war in Syria, and the negotiations between Israel and the Palestinians are reported to consume a substantial amount of the secretary’s time. The amount of bureaucratic ‘bandwidth’ dedicated to a region that, not long ago, was announced to be of declining importance to the energy-blessed US is impressive. This begs the question whether the Pivot – without a doubt a major and long-term policy decision, if followed through – still ranks highest on the agenda of the administration.

Two other top job decisions have raised expectations of a more interventionist foreign policy in Obama’s second term. He picked Susan Rice as National Security Advisor, after the Senate refused to confirm her easily for Secretary of State, and he nominated Samantha Power for the influential post of Ambassador to the United Nations. Both women are known for their advocacy of a more activist, interventionist US foreign policy, and their announcements have understandably been interpreted as a statement of President Obama’s support of their long-standing positions.

Foreign Portfolio Holdings of US Securities (by country)

More than one year into his second term, however, little of this influence is to be seen. Had the threatened attacks on Syrian installations taken place in 2013, this would no doubt have been attributed to the influence of Rice and Power. Yet this course was given up, most likely due to the immense war weariness of the US public and to avoid being drawn into the conflict. What emerged is a picture of a president considerably less eager to intervene abroad than his foreign policy team in the White House and the cabinet. While not surprising in its very existence, the contrast in his second term seems markedly stronger than during his first term or under his recent predecessors.

Two consequences: economization and a two-tiered military power

This combination of personality and parameters causes numerous structural and policy consequences, among which two stand out for their longterm impact: an increased economization of foreign policy and a global military presence essentially focusing on the conventional state-on-state capabilities in the Asia-Pacific.

Economization of foreign policy

According to the Pew study, the isolationist tendencies of the US public do not, tellingly, extend as far as economic engagement. An overwhelming majority – 66 % – of Americans believe that a greater US involvement in the global economy is “a good thing”. And indeed, one of the few obvious consistencies in President Obama’s conduct of foreign affairs is a marked economization of foreign policy. The impetus for the focus on economic and trade partnerships is natural, coming after the shock of the financial crisis. Even before 2008, however, concerns were raised with regard to the US’ dependence on foreign debtors in general, and its integral economic ties with China in particular. The complex creditor-debtor relationship of Beijing and Washington, and the resulting trade ties, are sure to influence the foreign policy agenda of every administration in the years to come.

Yet, while the roots of economization go deeper than his first inauguration, Obama has stepped up the pace. And he has explained the rationale for this decision. The Trans Pacific Partnership (TPP), intended to bolster the US economic integration into Asia, notably without and therefore against China, is a key pillar of the Pivot. In his remarkable speech in the Australian parliament in November 2011, President Obama laid out the main rationale for the rebalancing of US resources. He wants to use the economic dynamics and increasing prosperity of the vast Pacific region to support his highest priority as president: improving the US economy and creating jobs in the US.

The second major thrust to ‘economize’ foreign policy is the envisaged transatlantic free trade area (Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership, TTIP). The TTIP is instructive with regard to the US’ perspective on the future of transatlantic relations. With no major security challenge in Europe, at least none that might overstrain Europe’s potential capabilities, the current administration considers it time to move away from a securitybased relationship. While intended to complement the security bond of NATO, the TTIP is more likely to become the primary bridge over the Atlantic, resting on shared vital interests. This is even more bolstered by NATO’s apparent failure to develop into a global partner for the US, both in terms of ambitions and in terms of capabilities.

Not three years after the then US Secretary of Defense Robert Gates, in his landmark speech in Brussels in June 2011, warned NATO partners that the alliance was in danger of becoming irrelevant for the US, this has to a large degree become reality. For the domestic president Barack Obama, Europe is relevant for its economic power and the potentially job-creating dynamics of free trade. Militarily, it is irrelevant. Yet if Europe lives up to this challenge and strengthens both its Common Security and Defence Policy (CSDP) and the European element of NATO, this could have positive consequences for the genesis of a European foreign policy. The example of the first instance of “leadership from behind” by the US during the Libyan crisis in 2011, however, is not encouraging. European partners were not equal allies during the intervention, and nor was Europe united with regard to the policy options after the fall of Muammar Gaddafi. Critical gaps in capabilities such as intelligence, surveillance, target acquisition and reconnaissance platforms, combined with the ability to strike promptly and precisely, are not even near to being closed. The CSDP summit of late 2013, heralded with much fanfare by the member states, brought no progress. On the contrary, among the important member states the visions of the future of the CSDP seem to be increasingly divergent. This will only encourage the US to further follow the path of economization and to move away from Europe militarily, with profound implications for US military policy and posture.

The US military in a symmetric and asymmetric world

From 2008 at least, budget policy is defence policy. The US’ massive defence cuts, combined with the stated governmental priority of a rebalancing towards Asia, will lead to a military posture that intentionally limits military capabilities in large parts of the world, with long-term consequences. If implemented with the determination seen at the beginning, the Pivot towards Asia will effectively lead to a worldwide two-level military presence and operational focus of US forces: a predominantly ‘symmetric’, conventional presence in Asia focused on deterring the nation state of China; and a predominantly ‘asymmetric’, unconventional presence in Africa, South America and the Middle East, aimed at supporting fledging states and combatting terrorist threats. This will have important consequences for US force posture and doctrine.

As the Pentagon’s Fiscal Year 2015 defence budget proposal made clear, after more than a decade fighting largely unconventional wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, a substantial part of the US’ forces is rebounding towards more traditional threats. During the counterinsurgency campaigns of the last few years, the land forces of the Army and Marine Corps have gained organizational primacy vis-à-vis the strategic services of the Air Force and the Navy, while at the same time undergoing a profound process of organizational adaptation to conduct a variety of operations against elusive enemies in partly extreme terrain. The Air Force and Navy took an operational backseat, largely confined to supporting the ground campaign on the tactical level, yet resisting fundamental organizational change – for good reason.

Since 2010, the Air Force and Navy have based their future planning on the concept of AirSea-Battle, modelled after the AirLand-Battle concept of the 1980s. In essence, AirSea-Battle focuses on the seamless and effective integration of both services to create operational synergies and ensure strategic access against determined adversaries. While not directed against any specified enemy, or towards any concrete scenario, it is understood that the most plausible antagonist would be the Chinese armed forces, and the most probable theatre of operations the South China Sea. AirSea-Battle is, at its very core, state-centred, symmetric, and conventional.

Concurrently, the planned financial cuts in defence spending will affect the land forces disproportionately, reversing their expansion during two major ground campaigns. The US Army alone will be reduced from 570,000 soldiers in 2010 to between 440,000 and 450,000 by 2015. The US Marine Corps, meanwhile, will strive (albeit with good chances) for strategic and operational relevance. Hard choices will have to be made. The US is not in any form in military decline; it will remain for years the preeminent military in those regions, and against those opponents, that it deems critical. Here, choices in terms of regional focus and capabilities have to be made. The Pivot, if followed through, implicitly entails this decision: giving priority to a conventional strategic presence in the Pacific.

This bureaucratic and organizational realignment will in effect lead to a two-tier military posture worldwide.

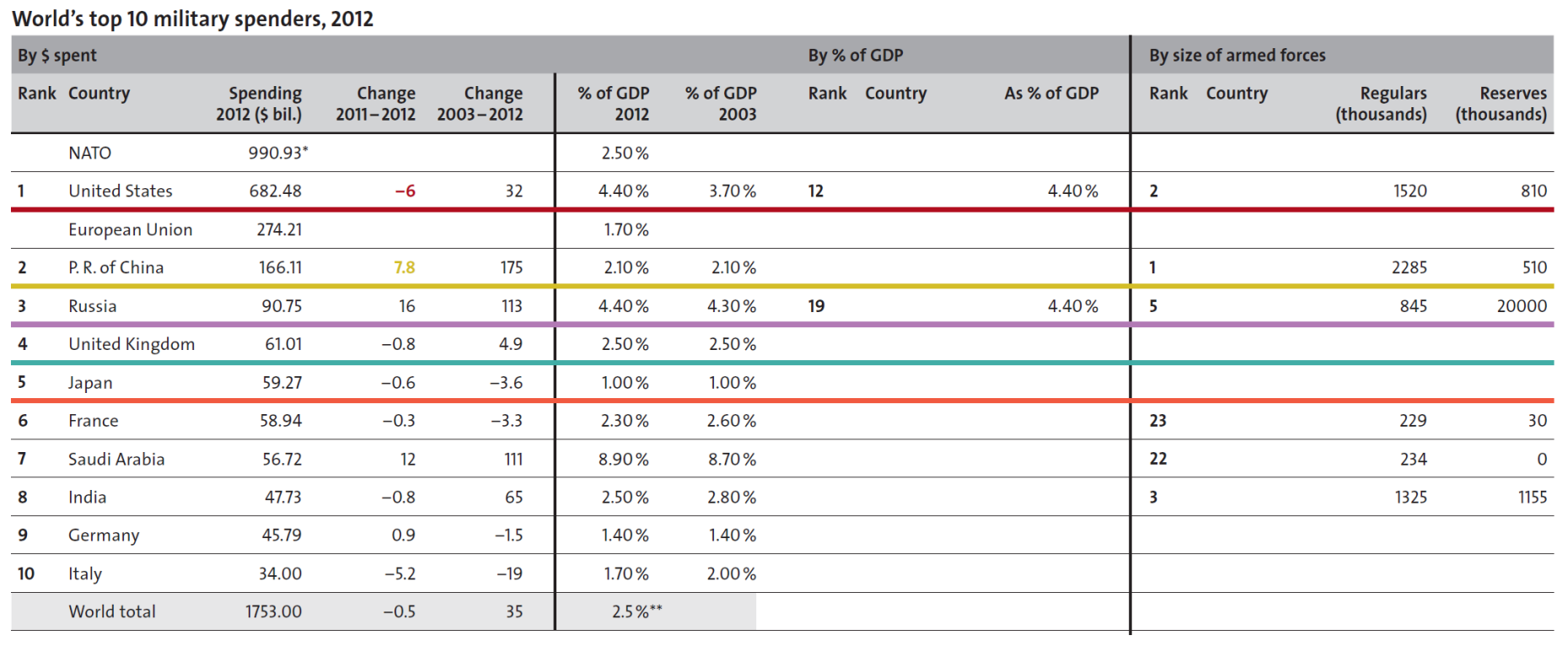

World's Top 10 Military Spenders

Top Military Spenders in USD(billions)

Military Spending by %GDP / size of armed forces

Despite calls for a ‘full spectrum force’ able to conduct all conceivable sorts of military operations, we will effectively see that one tier of US global posturing will be focused primarily on conventional threats, while the other focuses on unconventional ones. On the one hand, the Pacific theatre will thus develop into an area of a conventional, symmetric force posture to counter a traditional military challenge. On the other hand, most of the rest of the world will be subject to the manifold ‘lessons learned’ of Iraq and Afghanistan. In this area, the main security challenge for US forces emanates from global jihadists, mostly using the ungoverned territory of weak states to establish save havens from which, possibly, to attack the US. This threat is asymmetric and unconventional in nature. In this area, which effectively constitutes a large part of the world, the US will mostly rely on an indirect approach of security force assistance, support using critical niche technology, and, occasionally, strikes conducted primarily by special operations forces.

Of course, this effective two-tier military posturing will not predetermine how the US will use force in any eventual conflict; but it will set the background for the regular, ‘routine’ conduct of foreign policy. It is further not only about pure military posturing; it is a direct deduction from the strategic priorities of the US, and therefore determines to a large degree how most of the world will encounter US military power – and how the US exercises it.

Parameters will persist

People decide, parameters shape. Three parameters have been paramount in shaping President Obama’s foreign policy: the financial crisis, public war weariness, and the advent of shale gas and oil. Against this background, it is President Obama with his aversion to grand strategies, his centralized management approach to foreign policy and his domestic priorities shaping US foreign policy to a pattern best described as ‘strategic pragmatism’.

Among the fundamental results are a marked economization of the US foreign policy and a two-tier global military posture that will create path dependencies for US engagement in the future. For Barack Obama, his hitherto observed conduct of foreign policy leaves him liable to be seen, in hindsight, as indecisive, non-strategic, and overly focused on his domestic political agenda. That all can be changed through diplomatic successes – be it with regard to Iran, the Middle Eastern peace process, or the war in Syria.

What does that mean for the years after January 2017 when Barack Obama leaves office? Naturally, in a democracy with term limits for the highest office, people go short and parameters go long. Even if the financial crisis recedes from the front pages, its effects will be felt for decades, and it will leave its mark on people’s minds – voters as well as office holders. For the years ahead, any president will have to factor in an American public resenting large and long-term military commitments; and a reduced energy dependence on the Middle East will in turn reduce the strategic weight of this region for the US, if not nullify it. Even beyond Barack Obama, therefore, any US administration is likely to continue in a pattern of strategic pragmatism.