When Civil Conflict Ends

6 May 2014

By Anna Getmanksy for ISN

How do countries that experience revolutions and other forms of political violence fare in terms of political and economic development once conflict ends? Does it follow that these states become more democratic and prosperous compared to pre-conflict years?

These are important questions given that most forms political violence over the past 60 years has taken place within rather than between states. Consequently, these types of conflicts – particularly the ‘color’ revolutions of the former Soviet space and the ongoing political unrest in Syria and other parts of the Middle East – have been the focus of extensive public debate and academic research. In particular, scholars have spent a great deal of time trying to identify those factors that can predict their outbreak, as well as their duration, lethality and endpoint. The findings make for interesting reading.

Causes and Prospects

For instance, external pagelow per capita incomecall_made has been identified as a strong external pagepredictorcall_madeof where civil unrest and revolutionary activities are more likely to occur. When combined with low military and police capacities, as well as rough terrain and large territory, poverty provides a fertile breeding ground for rebellion and political unrest. That said, specific economic, political, religious, and external pageethniccall_made grievances are not always systematically associated with the onset of external pagecivil conflictcall_made, though this does not mean that they cannot cause rebellions due to possible selection effects.

Another important observation about these types of conflict is that even if they appear to have ended, there is a high likelihood that some form of political violence might re-emerge in the not-too-distant future. According to the UCDP/PRIO Armed Conflict Dataset, almost 50% of all intrastate conflicts involve more than one episode of fighting. Indeed, in the case of a ceasefire or a rebel victory, the chances of conflict re-emerging actually exceed the 50% threshold. Table 1 indicates that out of all possible outcomes, a government victory over opposing forces has the lowest rate of return to violence, followed by peace agreements.

These figures should not be interpreted causally, for example, by concluding that it is better to support the government and not the rebels. However, even if the data does not tell a causal story, it nevertheless suggests that restoring peace and stability in countries that experience domestic political violence is not an easy task, as evidenced by the ongoing unrest in Syria. A degree of prior planning with respect to the day after the political violence ends is also a necessity.

Outcome

Violence restarts

Violence does not restart

Government victory

30

41

Peace agreement

20

22

Ceasefire

23

14

Rebel victory

20

11

Low activity

99

41

Table 1: Outcomes of conflict episodes and future violence. Each cell includes the number of episodes of violence in the UCDP/PRIO dataset (1946-2012) that ended with these outcomes, and whether the conflict started again.

Economic Fallout

What’s far more certain, however, is that political violence and revolutions have adverse effects on post-conflict economies. Resources are inevitably depleted as a result of prolonged periods of unrest, and quite often cannot be used once violence ends. In addition, political violence of all hues results in the loss of human capital, either through conflict or refugee flows, which puts a further strain on a country’s economic development. For these reasons, one should expect economies to shrink during periods of internal conflict, and not to perform well for some time even after the violence ends.

However, there are also factors that can balance the negative impact of conflict on the economy. As the Syrian case shows, even though war destroys some sectors of the economy, it creates new activities and brings assistance from external players. These developments can prevent the total collapse of the economy during conflict, but it is not clear how they affect post-conflict economic growth.

Using UCDP/PRIO dataset and measures of per capita GDP from external pagethe Penn World Tablecall_made, my research compares the per capita income before the first conflict onset and after the end of violence in countries that have not experienced internal instability since 2003. Figure 1 depicts the comparison of income relative to country's geographical region. Number 1 on the vertical axis suggests that there is no difference in per capita income between countries that experience conflicts and those that do not. Values less (greater) than 1 on the vertical axis indicate that countries with conflict are poorer (wealthier) than their geographical region. On the horizontal axis, negative values depict years prior to the first onset, and positive values depict years since the last termination (conflict years omitted).

Figure 1: Per capita income of countries with conflicts relative to their region – before and after violence

Figure 1 suggests that until about 3 years prior to conflict, countries that are about to experience violence do not differ from their surroundings in terms of per capita GDP. The drop begins 2-3 years before the outbreak of violence, and is most noticeable in the year before violence begins. This is similar to what happened in the Syria, where the GDP plunged in 2010, a year before the outbreak of fighting. In post-conflict years, the graph shows that countries that have experienced violence perform noticeably worse compared to their geographical region (the average per capita income is about 75% of the average regional income).

One possible explanation could be that even though post-conflict countries are growing economically, their geographical region is growing at a faster pace. (I thank Tolga Sinmazdemir for pointing this out.) To investigate this possibility, I look at the absolute values of per capita income (at 2005 constant prices) before and after conflict. This comparison is depicted in Figure 2 and confirms this hypothesis: the average per capita income in post-conflict countries is growing, and it is higher than the pre-conflict income (this is interesting given that conflicts are known to be costly). However, taken together with Figure 1, the data suggest that the growth is slower than the average growth in the region, and the per capita GDP in countries that went through conflict is still lower than in the surrounding countries even 10 years after the end of violence. These patterns persist regardless of conflict outcome (peace agreement, victory, ceasefire, or low activity). Given that poverty is a strong predictor for the onset of civil war and revolutionary activity, this is mixed news, at best.

Figure 2: Absolute per capita GDP at 2005 constant prices ($US), before and after conflict

More Promising Signs?

Another important question with respect to post-conflict countries is whether they become more democratic than they were before conflict started. This is important because many of these conflicts are motivated, at least partially, by the desire to expand political and civil rights, as evident in Arab Spring events, and democratic institutions are associated with the external pageprovision of public goodscall_made, and external pagebetter human rights practicescall_made.

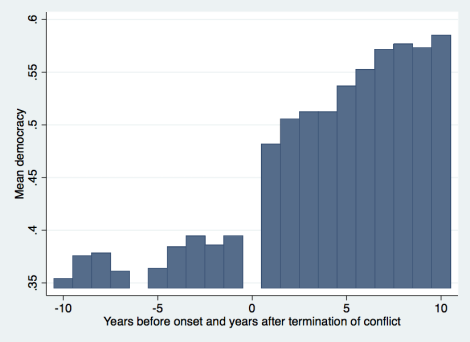

I investigate this question by comparing the level of democracy before and after conflict using external pagePolity IVcall_made indicators. Figure 3 depicts the average levels of democracy in countries with conflicts before and after conflict, relative to their geographical region. The vertical axis should be interpreted relative to the region, as in Figure 1. Figure 3 suggests that before conflict onset, countries that are about to experience violence are not different from their region. However, in the post-conflict period, countries that have experienced conflict are more democratic than the wider region.

Figure 3: Democracy before and after conflict, relative to other countries in geographical region (excluding countries with conflict).

Democracy is the rescaled polity score (1=most democratic, 0=most autocratic)

Finally, absolute levels of democracy depicted in Figure 4 also suggest that countries become more democratic following conflict cessation . And while some of these countries do not necessarily become fully-fledged democracies – Egypt, for example - they are nevertheless more democratic than before the outbreak of political conflict, and more democratic than some of their closest neighbors. In addition, the highest levels of democratization occur in countries where conflict is terminated with a peace agreement (the mean level of democracy is about 0.65 5 years after peace agreement; the mean level of democracy is 0.45 and 0.48 5 years after victory by government and victory by rebels, respectively).

Figure 4: Absolute levels of democracy before and after conflict.

Democracy is the rescaled polity score (1=most democratic, 0=most autocratic)

Conclusions

So does this mean that revolutions and other forms of political violence are bad for states and, indeed, the international system as a whole? Not necessarily. True, post-conflict states exhibit worse economic performance compared to their region. However, they also experience growth in per capita income, especially when compared to the pre-conflict years. In addition, those states that have overcome prolonged periods of political violence are generally more democratic than their immediate neighborhood. These are important observations given that democracy is important for stability, but insufficient economic development poses a threat to democratization. Nonetheless, since these countries continue to grow, if they do not relapse to violence and reach the external pageminimum threshold necessary for stable democracycall_made, they can expect to escape the cycle of political violence.