India and the Democratic Civil Peace

15 May 2014

By Corinne Bara for ISN

The claim that democracies rarely go to war with each other has largely withstood empirical scrutiny, even if experts disagree about external pagehow to explain itcall_made. In addition to a democratic peace between states, however, there may also be a democratic peace within them. In theory, the prospect of being voted out of office should put pressure on those in power to address popular grievances more effectively – thereby reducing the likelihood of violent conflict. Nevertheless, the evidence to support this relationship remains inconclusive. If a democracy is defined as a political system in which government offices are filled through contested elections (as in José Antonio Cheibub and co.’s external pageDemocracy-Dictatorship (DD) datasetcall_made), there were 95 democracies and 70 dictatorships (out of the 165 countries surveyed) in 2008. Comparing this data with the external pageUCDP/PRIO Armed Conflict Datasetcall_made [1] produces no evidence of a democratic civil peace. Of 138 civil conflicts between 1973 and 2008, 41 took place in democracies and 97 in dictatorships. This suggests that conflict may be more common in dictatorships than in democracies (with an annual conflict risk of 2.97% versus 1.74%), but it also contradicts the idea of a democratic peace within states.[2]

With eight active internal conflicts, India – the world’s largest democracy and one whose external pagestatus is largely undisputedcall_made – provides a powerful illustration of this. Deplorable though it may be that one third of external pageIndia’s sitting parliamentarianscall_made and of the external pagecandidates in the 2014 electionscall_made have criminal cases registered against them, elections in India are undeniably external pagefree and faircall_made, and turnout reached almost 60% in the 2009 election, a figure equivalent to the country’sexternal pageadult literacy ratecall_made. If, external pageas expectedcall_made, the incumbent Congress party loses the ongoing election, it will accept defeat without further ado. For the last two decades, however, India has averaged five or six active external pageconflictscall_made each year, and thousands of people have died in Hindu-Muslim riots.

How can India be so obviously a democracy and yet sustain such a high level of violence and conflict? On the whole, the answer may be that elections alone cannot guarantee a democratic civil peace, and that the postulated effect might only apply to certain kinds of democracies.

Wanted: Candidates for a democratic civil peace

There is evidence that external pageconsolidated democracies are more peacefulcall_madethan newly established ones, suggesting that the path to democracy (like the path to autocracy) is often violent.

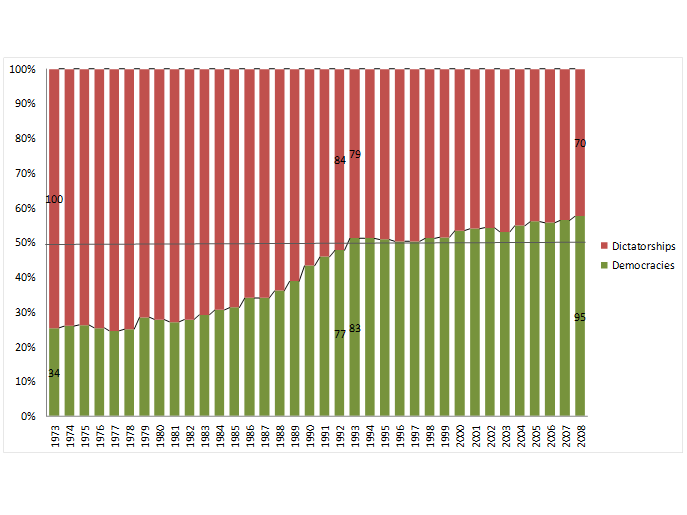

Since the 1970s (as shown below), democratic transitions have occurred in more than sixty countries.

Figure 1: Ratio of democracies vs. dictatorships, 1973-2008

(Data source: external pageDD datacall_made)

For a variety of reasons, the transitions in this ‘Third Wave’ of democratization were often violent. Generally speaking, democratic transitions tend to increase opportunities to organize and voice dissent, while institutions to channel this dissent remain underdeveloped. This means that some regimes get ‘stuck in the middle’ between autocracy and democracy, with former elites often unwilling to relinquish their privileges. When the Cold War ended, funding from the superpowers also dried up, giving international donor agencies external pageconsiderable leveragecall_made to pressure developing countries into democratic reforms in exchange for aid. Some of the deadliest conflicts took place in this context of ‘internationally mandated reform.’ In Burundi, multiparty elections were held in 1993 after external pagedonors had threatenedcall_made to withdraw aid. Three months later, the first Hutu president Melchior Ndadaye was assassinated by Tutsi members of the armed forces, sparking a civil war in which external pagemore than 300,000 have diedcall_made.

This example illustrates why newly empowered actors in young democracies often question whether their predecessors in power are genuinely committed external pageto the democratic processcall_made and ready to accept an electoral defeat. Lars-Erik Cederman and co. have external pagedemonstratecall_maded that elections are a dangerous time for young democracies, even if the risk of conflict is weaker than expected and typically limited to the first two competitive elections. This ‘ external pagetwo elections rulecall_made’ is a useful criterion for distinguishing between consolidated and new democracies. Another one is that democracy is accepted as the 'only game in town' and firmly embedded in a country’s political culture. But while the latter evades simple measurement, the former is not entirely convincing. Out of the 41 conflicts in democracies, only 18 of those democracies had existed for fewer than 10 years while 23 had existed for 10 years or more. Although the annual risk of conflict is lower in consolidated democracies than in new democracies (1.38% versus 2.63%), the 18 civil conflicts that have occurred in consolidated democracies mean that it provides no guarantee of a democratic civil peace. India, for instance, is currently holding its 16th national elections, and the incidence of civil conflict has not decreased in more than 60 years of democracy.

While the ‘Third Wave’ of democratization increased the number of formal democracies, external pageelections alone may not be enoughcall_made to address deep-seated social problems. Another way of incorporating more demanding criteria into the democracy-dictatorship classification is through the idea of liberal democracy. A external pageliberal democracycall_made not only holds regular, inclusive, competitive, and fair elections, but guarantees the protection of basic political and civil liberties including the freedom of expression and belief, the freedom of association, and the protection of minority and physical integrity rights. For many — at least in the West — a democracy that fails to guarantee these protections is external pagehollow, weak and ineffectivecall_made. In liberal democracies, these rights and guarantees should reduce the number and severity of grievances as well as increase the effectiveness of conflict resolution mechanisms – meaning that liberal democracies should experience fewer civil conflicts.

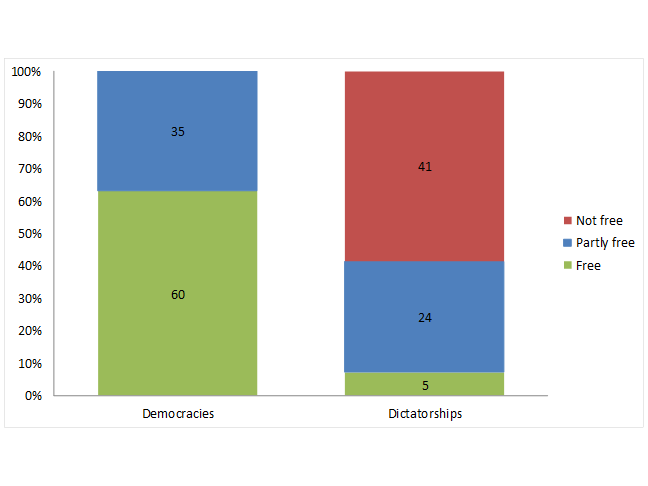

The most prominent measure of political rights and civil liberties is the external pageFreedom House (FH)call_made index, which classifies countries as free, partly free, or not free. While there are five free dictatorships (as shown below), there are no unfree democracies.

Figure 2: Freedom House ratings for democracies and dictatorships in 2008

(Data sources:external pageFreedom Housecall_made, external pageDD datacall_made)

Despite this, there is also no sign of a liberal democratic civil peace. Although the annual conflict risk in liberal democracies (1.35%) was only half that of its less-than-liberal counterparts (2.82% for partly free democracies, 2.94% for partly free democracies and dictatorships together), there were still 23 civil conflicts in liberal democracies.

Notably, India again features on the list. Amid persistently high levels of internal conflict, it has been considered ‘free’ since 1977 (with an interruption between 1991 and 1997).

Good governance and the democratic civil peace

The high level of violence and conflict in India illustrates that there is even more to democracy than free and fair elections and the protection of political and civil liberties. This point can be illustrated through a timely question: why do India’s elections take so long?

At 36 days, the ongoing elections in India are the longest in the country’s history. And this is not because India has the largest electoral population in the world with almost external page815 million potential voterscall_made. According to the former election commissioner SY Qureshi in an interview with the external pageBBCcall_made, the length of the elections “boils down to a single reason – security.” Because the local police are considered partisan, the central government must move federal forces all over the country, often in trains and buses, in order to ensure that elections are free and fair. This highlights an under-appreciated aspect of democracy: the ability of a democratic government to actually implement its policies and decisions. It also moves the focus away from the formal design of democratic institutions to how they actually function in practice — from government to governance, if you will.

In a recent external pagestudycall_made, Håvard Hegre and Håvard Mokleiv Nygård demonstrate that external pagegood governancecall_made has a greater impact on a government’s ability to prevent civil conflict than how formally democratic its institutions are. In badly governed countries, citizens not only have more grievances, because policy-making fails to benefit the public at large, they are also more likely to see the government as responsible for these grievances, because it is unwilling or unable to implement change. Well-governed countries, on the other hand, successfully implement their decisions through the administrative apparatus; they ensure that contracts and property rights are enforced; they guarantee the rule of law through nonpartisan police forces and functioning local courts; they control corruption to ensure that public funds reach their intended recipients; they choose economic policies that serve the broader public rather than a narrow elite; and they do not undermine formal minority protections through informal discrimination.

Hegre and Nygård provide external pageindicescall_madefor each of these aspects of good governance. If we average those indices and take the median value over all years and democracies as a cut-off point, there were 40 well-governed democracies in 2008, and 55 deficient democracies (as well as nine well-governed dictatorships). All OECD member-states except Israel, Mexico, and Turkey are well-governed democracies, in addition to Cape Verde, Costa Rica, Croatia, Cyprus, Latvia, Lithuania, Mauritius, Panama, Taiwan, and Uruguay.

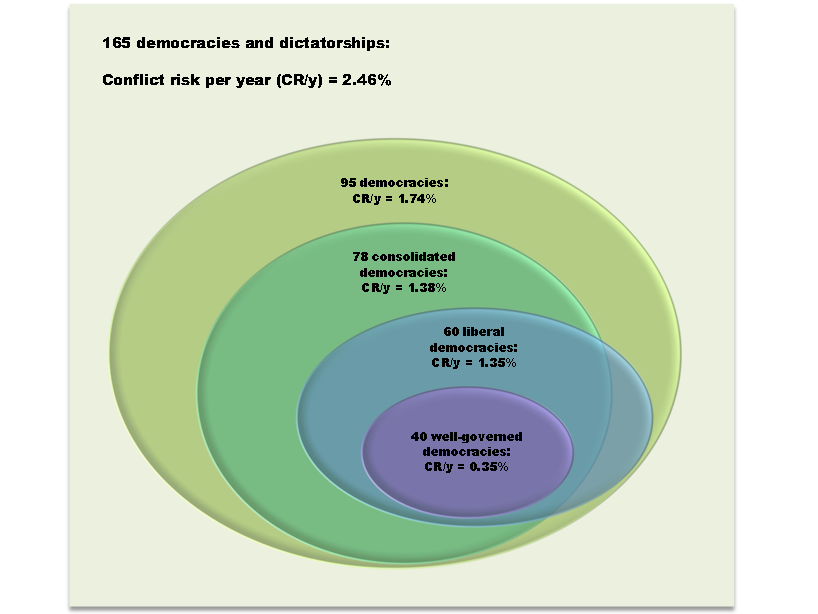

Among these countries, there is indeed a democratic civil peace. Of the 41 conflicts in democracies between 1973 and 2008, only 4 took place in well-governed democracies.[3] Good governance is so important that well-governed democracies had a 10 times lower risk of conflict compared to other democracies (0.35% versus 3.09%) and compared to all other regimes combined (0.35% versus 3.00%).

The figure below summarizes the remarkable reduction in conflict risk as the definition of democracy becomes more substantive:

Figure 3: Distribution of different subtypes of democracy in 2008, with information on the annual risk of conflict as estimated between 1973 and 2008.

(Data sources:external pageDemocracy-Dictatorship (DD) datasetcall_made, external pageUCDP/PRIO Armed Conflict Datasetcall_made, external pageFreedom House (FH)call_made, external pageHegre & Nygard 2014call_made)

This figure suggests that a democratic civil peace does exist – though only for the most substantive democracies. While these are also mainly external pagewealthy countriescall_made, the strong effect of good governance does not disappear if we control for income level. India, by the way, is not a well-governed democracy according to this classification. Its governance score in 2008 was better than only 40% of all democracies. Though the country is actually quite well-governed for its low income level, and the quality of its bureaucratic apparatus and economic policies is surprisingly high, it performs poorly with regard to corruption, political exclusion and repression. For India and for policy sequencing in general, the good news is that the separate aspects of good governance mentioned above are also external pageindividually related to a decreased risk of conflictcall_made. This means that reform in any area of good governance can make an important contribution to the democratic civil peace.

[1] A civil conflict is defined as armed violence between the government and a non-government party which results in at least 25 battle-related deaths per year.

[2] And if income level is controlled for, the difference between democracies and dictatorships disappears altogether.

[3] The four conflicts, by the way, are the Lebanese Civil War in 1975; the Basque rebellion in Spain in 1978; the last round of the Northern Ireland conflict in the UK in 1998; and the intra-state conflict between the government of the US and al-Qaida that began in 2001 (and this final case may be questionable because the attackers were not US citizens, and almost no fighting has taken place on US soil, except for the initial attacks).