Constitutional Reform and Violent Conflict: Lessons from Africa, for Africa

16 May 2014

By Alan Kuperman for Climate Change and African Political Stability (CCAPS) Program

This report was external pageoriginally publishedcall_made by the external pageClimate Change and African Political Stability (CCAPS)call_made program at the external pageRobert S Strauss Center for International Security and Lawcall_made in July 2013.

Can deadly internal conflict be prevented, or at least significantly reduced, by changing a country’s domestic political institutions? This might seem an obvious and important question, especially for Africa, which recently has suffered the most such violence – in Rwanda, Congo, Darfur, and elsewhere. Yet, this continental puzzle had never been addressed in a rigorous, comparative manner prior to the CCAPS project on Constitutional Design and Conflict Management (CDCM) in Africa.

Starting in 2010, the CDCM project approached the subject in three steps. First, it assembled seven of the world’s leading experts on constitutional design, conflict management, and African politics. Each of these scholars wrote a detailed case study of an African country, identifying how at key turning points the domestic political institutions either mitigated – or exacerbated – political instability and violence. This provided vital lessons about the types of domestic political institutions – or “constitutional design” – that are best for peacefully managing conflict. Second, the project compiled the first-ever database of constitutional design in Africa. This revealed that most African countries have highly centralized political institutions, which according to conventional wisdom are prone to foster conflict. Third, the project integrated these two pieces of the puzzle – comparing the political institutions that Africa currently has to the type that might reduce violence – to develop policy prescriptions for foreign aid aimed at promoting democracy and good governance.

Counter-intuitively, the CDCM project does not recommend promoting the constitutional design typically prescribed by academics for ethnically divided societies – which is based on decentralization and other explicit accommodation of ethno-regional groups – because it would be too different from what currently exists. Attempting such radical change would likely result in halfmeasures that could backfire by exacerbating political instability and violence, contrary to their intent. Instead, the project recommends promoting gradual reform of Africa’s existing, centralized constitutional designs by counterbalancing them with liberal institutions, especially the separation of powers – including a strong parliament, independent electoral commission, and judicial review. The case studies and database suggest that such evolutionary reform of constitutional design could promote political stability and reduce the incidence of deadly conflict in Africa.

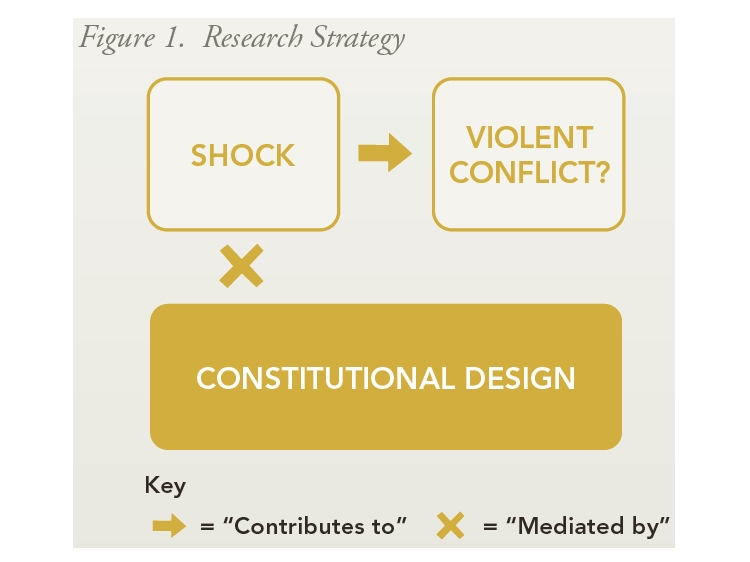

A New Research Strategy: Shocks and Outcomes

Figuring out which constitutional designs are better or worse for conflict management in Africa is a methodological challenge. One might be tempted simply to examine the correlation between political institutions and violence across the continent. This could be misleading, however, because some countries may remain peaceful not because of beneficial constitutional design but rather the dumb luck of being dealt an easy hand. Contrarily, other countries may succumb to violence despite beneficial domestic political institutions because they have the misfortune to be overwhelmed by events, such as the spillover of war from a neighboring country. To control for this variation, the CDCM project focuses on moments when countries are confronted by particularly difficult challenges – “shocks” – and then explores how constitutional design mediates their impact (see Figure 1).

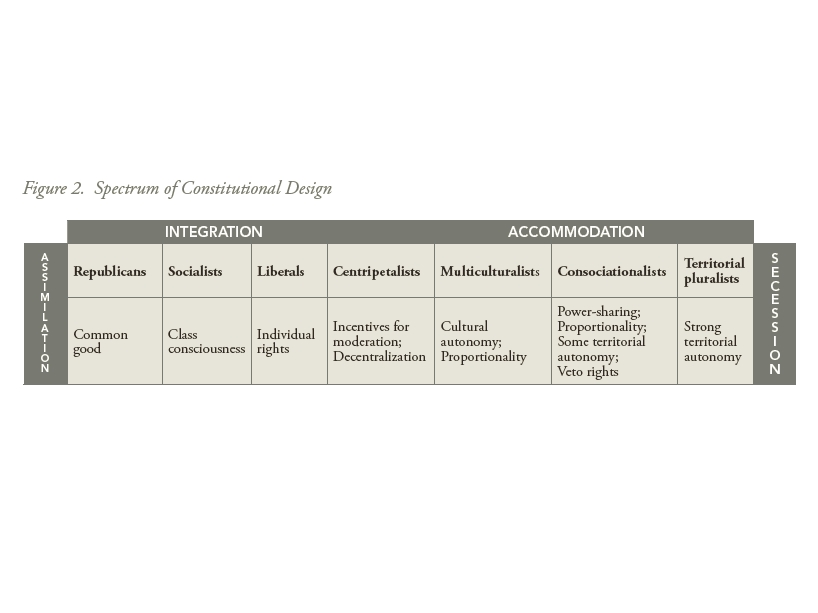

Shocks are defined as relatively sudden changes that affect the distribution of resources and power in a country, whether arising from economic, political, demographic, or environmental dynamics. Each shock creates societal winners and losers, which scholars explain can lead to violence via various means, including grievance,external page[1]call_made opportunities for predation,external page[2]call_made state weakness,external page[3]call_made or insecurity. external page[4]call_made Economic shocks include sharp changes in terms of trade, as well as resource windfalls or shortages. Political shocks include disputed elections, term-limit violations, land redistribution, assassinations, or other political acts – typically domestic but potentially foreign. Demographic shocks include sudden migration flows and epidemics. Environmental shocks include floods, droughts, famine, and rapid environmental degradation. In some instances, a shock may lead to an outcome that serves as yet another shock, in a domino effect. Constitutional design is defined as the formal and informal structures of countrywide governance. The CDCM project sought especially to engage the debate, among both academics and practitioners, regarding two opposing strategies of constitutional design. “Accommodation” provides guarantees to societal groups based on identity or geographic location, such as proportional representation, federalism, autonomy, quotas, economic redistribution, and vetoes. “Integration,” by contrast, aims to erode the political salience of groups based on identity or location, by instead promoting a single, unifying identity. Between these two ideal-types lies a spectrum of constitutional design strategies (see Figure 2). external page[5]call_made

Seven Case Studies

Each of the seven experts wrote a chapter-length case study. Below are thumbnail sketches of the main findings.

Burundi: Accommodation May Backfire without Precautions

This case contrasted two attempts at constitutional accommodation to mediate the shock of ending minority rule, which resulted in starkly different outcomes. The first attempt, in 1993, tragically led to civil war and genocide. By contrast, the second attempt, in 2005, appears successfully to have promoted peace, equity, and ethnic reconciliation. external page[6]call_made In each instance, the constitutional design aimed to accommodate both the traditionally dominant ethnic Tutsi minority, via security guarantees and representation, and the historically oppressed ethnic Hutu majority, via democratization. The study finds three main explanations for the far superior outcome of the latter effort. First, the revised accommodative institutions offered firmer guarantees of representation to the ethnic minority. Second, a regional peacekeeping force helped reduce the physical security concerns of that minority. Third, sufficient time had passed since the initial reform effort for the ethnic minority to be reconciled to its loss of political dominance. Although the case thus confirms the beneficial potential of accommodation, it also highlights an important caveat – that accommodation by itself cannot mitigate intense group insecurity. Accordingly, transitions of power should be implemented gradually, and be accompanied by third-party security guarantees, rather than relying solely on accommodative domestic institutions. Burundi also illustrates the counter-intuitive lesson that explicit acknowledgement of ethnic identity by government institutions can help reduce both the political salience of identity and the proclivity to inter-ethnic violence. This has important implications for neighboring Rwanda, whose government is attempting to mitigate a similar history of inter-ethnic violence with the opposite strategy – denying the existence of group identities – which seems inversely to be heightening ethnic salience and tensions. external page[7]call_made

Sudan: The Hazards of Piecemeal Accommodation

The 2005 Comprehensive Peace Agreement (CPA), which successfully ended a long-running north-south civil war, represented a major constitutional accommodation to the country’s south, including a pledge (subsequently honored) to hold a secession referendum after six years. This study explores the two main shocks entailed by implementation of the agreement: first, in 2005, the sharing of power between adversaries who had fought each other for more than two decades; second, in 2011, the south’s vote to declare independence. Both events satisfy the project’s definition of “shock” – because they represent a sudden change in the balance of power and resources – so it is important to examine how the agreement’s constitutional design mediated each. external page[8]call_made Although there has been no recurrence of full-blown war between the north and south, local violence has erupted, not only in the disputed border area of Abyei, but also in other areas of the north (Blue Nile and South Kordofan states) and the south (Jonglei, Unity, Upper Nile, and Warrap states). The study finds that the CPA’s institutions to regulate core north-south issues did successfully foster compromise and peaceful management of conflict between the two sides, with assistance from international engagement. But the CPA failed similarly to establish political institutions to mediate interactions among the contending groups within each region, thereby contributing to the outbreak of violence in both the north and south, exacerbated by cross-border support to militants. The case thus illustrates the dangers of inequitable accommodation. The 2005 agreement made significant concessions only to the most violent opponent of the government, while essentially ignoring other aggrieved groups. “Comprehensive” was thus a misnomer. The flawed design not only permitted the grievances of other groups to fester, but aggravated them and encouraged these groups to resort to violence in hopes of earning similar accommodation. This experience suggests that accommodation must be equitable if it is to buffer effectively against shocks.

Ghana: Liberal Institutions

Mitigate Perils of Integration This study explores how and why the country has remained peaceful in the face of repeated shocks, despite having a highly integrative constitutional design, which many scholars claim is suboptimal for conflict management. external page[9]call_made The four shocks under examination are the construction of the Volta Dam that displaced 80,000 people in the 1960s, and then the turbulent elections of 1992, 2000, and 2008, which entailed accusations of electoral fraud, boycotts by opposition parties, and the defeat of incumbent presidents. Although each shock produced some political conflict, none resulted in significant violence. The beneficent effect of key individuals and culture cannot be excluded in Ghana, but several aspects of constitutional design also helped foster non-violent outcomes. Since 1992, for example, the president has been limited to two terms, thereby offering political opponents hope that they can accede to the top office peacefully, rather than having to fight for it. Although the government’s formal institutions are highly integrative, including first-past-the-post legislative elections, one informal aspect of constitutional design is highly accommodative – namely, by tradition, the cabinet and other executive positions are filled to reflect the country’s ethno-regional diversity. This may produce an effect similar to formal accommodative institutions, such as quotas or proportional representation. Perhaps most important, liberal institutions – including free media, an independent electoral commission, and courts with the power of judicial review – provide a separation of powers that can check abuses by the executive. Facilitated by these factors, Ghana’s integrative institutions produce many of the benefits typically ascribed to centripetal constitutional design: namely, there is a two-party system in which politicians make cross-group appeals, coalitions are fluid, power alternates, and the political salience of group identity diminishes over time.

Kenya: Backsliding on Accommodation Perpetuates Electoral Violence

This study explores how, since the late 1980s, the country’s constitutional design, characterized by partial accommodation, has failed to buffer four major shocks to its political system.external page[10]call_made The result of these shocks typically has been mid-level violence, followed by only marginal constitutional reform, leaving the system vulnerable to the next shock. The shocks examined are as follows: 1) In the early 1990s, popular demands for a multiparty system, combined with donor aid cutbacks; 2) In the mid-1990s, violent riots and protests; 3) From 2003-2005, the combination of three successive tremors, arising from the demise of incumbent parties and coalitions; and 4) In late 2007, accusations of a stolen election. Three broad lessons emerge. First, the integrative aspects of the country’s constitutional design, including a strong presidency, fostered and then failed adequately to buffer a series of economic and political shocks. Second, the constitutional design historically reinforced ethnic dominance, which contributed to a protracted national stalemate over that design. Third, endogenous and exogenous shocks eventually gave rise to a more substantial constitutional reform in 2010, but the robustness of these modified institutions will not be revealed until they are tested by future shocks.

Nigeria: Federalism Requires More Devolution

This study examines the effects of three shocks arising from petroleum extraction in the country’s Niger Delta region. external page[11]call_made The first shock was the discovery of oil in the 1960s, which created a major revenue windfall that spurred secession by the Biafra region (that includes the Delta), leading to civil war and massive civilian victimization. The second shock was the pervasive environmental degradation by the oil industry that became politically salient in the 1990s, spurring a new rebellion. The third shock was the oil price spike of the 2000s, which magnified both the resources available to militants and their demands, thereby escalating the rebellion. Nigeria’s constitutional design has long contained elements of accommodation, notably federalism and requirements for diverse regional representation in government institutions. The case study demonstrates, however, that such limited devolution has proved inadequate to address local grievances about oil revenue-sharing and environmental justice in historically neglected areas populated by ethnic minorities. Except for federalism, the Nigerian government is highly centralized in its executive, legislative, and fiscal institutions, while lacking the resources to manage complex issues in the periphery. Prospective reforms to increase revenue-sharing and to devolve political authority to the community level may offer the best chance of reducing grievance and persistent rebellion in the Niger Delta.

Senegal: Inefficiency of Hyper-Centralization

This study explores how the country’s highly centralized constitutional design has mediated two shocks: rain-induced flooding that has produced widespread population displacement around the capital of Dakar; and secessionist rebellion in the province of Casamance. external page[12]call_made It finds that the highly empowered president has been able to take unilateral actions to address shocks superficially, thereby buffering their effects temporarily and averting large-scale violence, but without the urgency or ability to address the underlying vulnerabilities. As a result, the country’s populace remains persistently susceptible to shocks, and thus moderately aggrieved, but it has not yet resorted to large-scale, extra-systemic violence. To provide better protection against shocks, such a hyper-centralized constitutional design requires one of two types of reform. The first option is accommodation, such as devolving authority to local officials who could be more responsive to local concerns. The alternative is to bolster institutional checks on the executive, such as a strong legislature and independent judiciary, to foster greater accountability to constituents.

Zimbabwe: Exclusionary Authoritarianism Exacerbates Shocks

This study assesses how the country’s increasingly centralized and authoritarian constitutional design over the past three decades has mediated the effect of three shocks on political stability and inter-ethnic relations. external page[13]call_made At independence, the country’s constitutional design contained aspects of accommodation, both formal and informal, for minorities. The small White community was constitutionally ensured representation in the legislature and protection of property. The main Black minority ethnic group, the Ndebele, had been integrated into the ruling party (dominated by the ethnic majority Shona) after allying with it during the preceding war of independence. The first shock, in the early 1980s, was the emergence of violence between the government and its formerly allied, ethnic Ndebele paramilitaries. The outcome was the Gukurahundi massacres by the state of an estimated 20,000 Ndebele in the region of Matabeleland, eviscerating the informal accommodation toward this minority. The second shock, in the year 2000, was the defeat of the regime’s constitutional referendum. The result was the Third Chimurenga – the seizure and occupation of White-owned farms – which led to a breakdown of law and order, out-migration of White farmers, economic decline, and the effective end of the formal accommodation of Whites. The third shock was the 2008 election victory by the opposition Movement for Democratic Change (MDC). This led to the regime’s violent suppression of the opposition (Operation Ngatipedzenavo), followed by a nominal power-sharing agreement that effectively reversed the electoral outcome.

The case demonstrates, most obviously, that exclusionary authoritarianism can only temporarily suppress domestic opposition via force, because the government’s violence exacerbates economic decline and other sources of unrest. Less obviously, the study reveals a potential silver lining. President Robert Mugabe’s three decades of increasingly exclusionary and oppressive rule have helped unite his opponents across ethnic lines to forge perhaps the most inclusionary political alliance in any African country, comprising Shona, Ndebele, and Whites. This offers some hope for a future political transition in Zimbabwe.

Lessons Learned

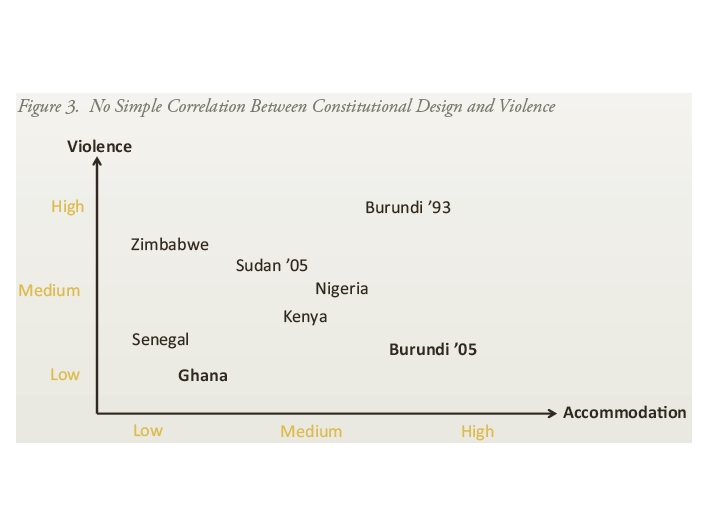

The broad lesson from the case studies is that neither of the two opposing constitutional approaches – integration or accommodation – is necessary or sufficient for buffering against shocks, but that each may do so if institutionalized appropriately. Indeed, as illustrated in Figure 3, the two most successful constitutional designs in the case studies – Ghana and Burundi-2005 – lie on opposite ends of the integration-accommodation spectrum. If implemented poorly, however, either approach can leave a society highly fragile to shocks, which may trigger instability, up to and including civil war and genocide.

The main danger of integration is that it tends to concentrate power in the hands of an executive that may be unaccountable, and therefore insufficiently responsive, to large segments of society. This can breed grievance among the neglected population, compelling the executive to rely on a narrower base, which further exacerbates societal resentment in an escalatory spiral. In such a situation, a shock can magnify grievance and create opportunities for offensive or preemptive violence by the government or its domestic opponents. Five of the seven cases – Kenya, Nigeria, Senegal, Sudan, and Zimbabwe – illustrate that pathology. This hazard of integration can be mitigated in two, very different ways, according to the case studies. One option is exemplified by Ghana, which balances its integrative design and strong executive with liberal institutions – including term-limits, courts with the power of judicial review, and an independent electoral commission – offering reassurance to the political opposition about a peaceful path to power. In this context, the country’s integrative electoral mechanisms – including first-past-the-post elections in a two-party system – encourage cross-group appeals by politicians, thereby fostering fluid, pre-election coalitions of societal groups, whose identity differences are thus gradually eroded.

The other option, accommodation, is the more obvious constitutional strategy for conflict management, because it addresses grievance through direct appeasement. This can work, but entails risks of backfiring gravely if not institutionalized appropriately. Three of the seven cases – Burundi, Kenya, and Sudan – illustrate the potential of accommodation. Burundi greatly reduced persistent interethnic tension and recurrent violence, and even the salience of identity, by accommodating both the Hutu majority and Tutsi minority in its 2005 constitution. Kenya broke its cycle of election-related, inter-tribal violence by adopting accommodative constitutional reforms in 2010. Sudan successfully ended decades of north-south civil war by accommodating the south via a referendum on secession.

But two of these cases also illustrate the dangers of poorly implemented accommodation. Burundi, in its first attempted transition to democracy, made the error of accommodating the ethnic majority too quickly, without adequate protection or socialization of the traditionally dominant ethnic minority. The tragic result was that the minority resorted to lethal force to retain its security and prestige, culminating in genocide and civil war. The lesson is that accommodation should be pursued in an evolutionary rather than revolutionary manner, providing sufficient time and security guarantees to enable traditionally dominant groups to overcome their psychological obstacles to surrendering power. Sudan made the error of accommodating only the country’s best-armed opposition groups, in the south, by permitting secession. This not only failed to accommodate other aggrieved groups in the north and south, but encouraged them to view violence as the path to accommodation. The consequence has been escalation of civil war and civilian victimization in both rump Sudan and South Sudan. The lesson is that accommodation should be institutionalized in an equitable rather than selective and discriminatory manner, if it is to provide a buffer against shocks.

Constitutional Tendencies in Africa

The CDCM project also compiled the first database of constitutional design in all of Africa, coded on a spectrum from integration to accommodation. external page[14]call_made This coding relies on three separate but interrelated institutional dimensions – executive, legislative, and administrative – including both de facto and de jure measures as of early 2011. As illustrated by a summary of the findings (see Figure 4), African countries have a strong bias towards integrative constitutional design. The two main elements of such integration are directly-elected presidents and centralized administrative structures that limit identity-based politics.

Policy Recommendations

Given that most African countries have highly integrative constitutional designs, which leave them susceptible to shocks, foreign aid to promote democracy and good governance could follow either of the two strategies identified above. One option would be to promote a radical transformation of domestic institutions from integrative to equitably accommodative. The alternative would be to promote only marginal changes in constitutional design by complementing the existing integrative institutions with liberal elements – such as term limits, empowered legislatures, and independent courts and electoral commissions – to counter-balance and thereby mitigate the pathologies of strong executives.

In theory, either pathway could work. In practice, however, it is difficult for outsiders to induce major changes in a country’s constitutional design, due to countervailing dynamics of culture, politics, resistance to perceived neo-imperialism, and historically rooted path dependency. external page[15]call_made As a result, foreign pressure to adopt full accommodation could well result in only piecemeal reform that is inequitable or provides inadequate guarantees to insecure groups, raising the grave risks illustrated by Burundi and Sudan (see Figure 5). Accordingly, aid donors should consider instead promoting liberal reforms of Africa’s existing, integrative constitutional designs – rather than their radical replacement with accommodative designs – despite the general academic preference for the latter, if they wish to foster both peace and democracy in Africa.

external page[1]call_made Lars-Erik Cederman, Andreas Wimmer, and Brian Min, “Why Do Ethnic Groups Rebel? New Data and Analysis,” World Politics 62 (2010): 87-119.

external page[2]call_made Paul Collier, Anke Hoeffler, and Dominic Rohner, “Beyond Greed and Grievance: Feasibility and Civil War,” Oxford Economic Papers 61, 1 (2009): 1-27.

external page[3]call_made James D. Fearon and David D. Laitin, “Ethnicity, Insurgency, and Civil War,” American Political Science Review 97, 1 (2003): 75-90.

external page[4]call_made Barbara F. Walter, “Designing Transitions from Civil War,” in Civil Wars, Insecurity, and Intervention, eds. Barbara F. Walter and Jack Snyder (New York: Columbia University Press, 1999), 38-69.

external page[5]call_made For further information on the methodology, see Alan J. Kuperman, “Can Political Institutions Avert Violence from Climate Change?” CCAPS Research Brief No. 1 (Austin: Robert S. Strauss Center for International Security and Law, 2011).

external page[6]call_made Analysis based on the CDCM case study by Filip Reyntjens, Professor of African Law and Politics, Institute of Development Policy and Management, University of Antwerp, in Belgium.

external page[7]call_made John McGarry, Brendan O’Leary, and Richard Simeon, “Integration or Accommodation? The Enduring Debate in Conflict Regulation,” in Constitutional Design for Divided Societies: Integration or Accommodation? ed. Sujit Choudhry (Oxford University Press, 2008), p. 69, Table 1.

external page[8]call_made Analysis based on the CDCM case study by Karly Kupferberg and Stefan Wolff, Department of Political Science and International Studies, University of Birmingham, in the United Kingdom.

external page[9]call_made Analysis based on the CDCM case study by Justin Orlando Frosini, Assistant Professor, Department of Law, Bocconi University, in Milan, Italy, and Director, Center for Constitutional Studies and Democratic Development (CCSDD), in Bologna, Italy.

external page[10]call_made Analysis based on the CDCM case study by Gilbert M. Khadiagala, Chair of the Department of International Relations, and Jan Smuts Professor, University of the Witwatersrand, in Johannesburg, South Africa.

external page[11]call_made Analysis based on the CDCM case study by Eghosa E. Osaghae, Vice Chancellor and Professor of Comparative Politics, Igbinedion University, in Okada, Nigeria.

external page[12]call_made Analysis based on the CDCM case study by I. William Zartman, Hillary Thomas-Lake, and Arame Tall.

external page[13]call_made Analysis based on the CDCM case study by Andrew Reynolds, Chair of Global Studies, and Associate Professor of Political Science, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

external page[14]call_made Analysis based on the CDCM study by Eli Poupko, J.D., who is a Ph.D. Candidate, LBJ School of Public Affairs, at The University of Texas at Austin.

external page[15]call_made Donald Horowitz, “Constitutional Design: Proposals Versus Processes,” in The Architecture of Democracy: Constitutional Design, Conflict Management, and Democracy, ed. Andrew Reynolds (Oxford University Press, 2002): 15-36.