Mind the Gap: Airpower in the Asia-Pacific Region

15 Oct 2014

By Paul Pryce for Offiziere.ch

This article was external pageoriginally publishedcall_made by external pageOffiziere.chcall_made on 2 October 2014.

With Japan external pageseeking to marketcall_made its new external pageSōryū-class diesel-electric submarinecall_made to Australia and other Asia-Pacific countries, it is clear the region’s arms race is set to continue for many more years to come. Observers have noted external pageconsiderably increased defence expenditures by China, Vietnam, and the Philippinescall_madeover the past few years, as each country struggles to gain a strategic advantage in maritime power or coastal defence. But airpower is a notable exception to this. A survey of Asia-Pacific air forces indicates a relative lack of procurement projects, suggesting that many countries in the region are willing to cede air superiority to China.

The external pageVietnam People’s Air Forcecall_made already operates 24 external pageSukhoi Su-30 multirole fighterscall_made and is in the process of acquiring another 12 from Russia. Aside from this Vietnamese acquisition, the only other significant orders among the Southeast Asian states is Indonesia’s contract withexternal pageLockheed Martincall_made for 21external pageF-16 Fighting Falconscall_made and the external pagePhilippine Air Force’scall_made recent agreement withexternal pageKorea Aerospace Industriescall_made to provide 12 external pageFA-50 Golden Eaglescall_made. It is also important to note that the remainder of the combat aircraft available to these countries consist predominantly of second-generation fighters like theexternal pageMiG-21call_made or the external pageNorthrop F-5E Tiger IIcall_made.

Elsewhere in the Asia-Pacific region, South Korea is working hard to replace its own contingent of F-5E Tiger II’s with a total of 60 FA-50 Fighting Eagles over the course of the decade. But all of this pales in comparison to China’s ongoing production of combat aircraft. The external pagePeople’s Liberation Army Air Forcecall_made (PLAAF) has at its disposal more than 1,600 combat aircraft, including 165 external pageShenyang J-11 air superiority fighterscall_made. The J-11 is a fourth-generation fighter based largely on the design of the external pageSukhoi Su-27call_made and was intended largely as a competitor to the external pageEurofighter Typhooncall_made, external pageDassault Rafalecall_made, and the external pageF-15 Eaglecall_made.

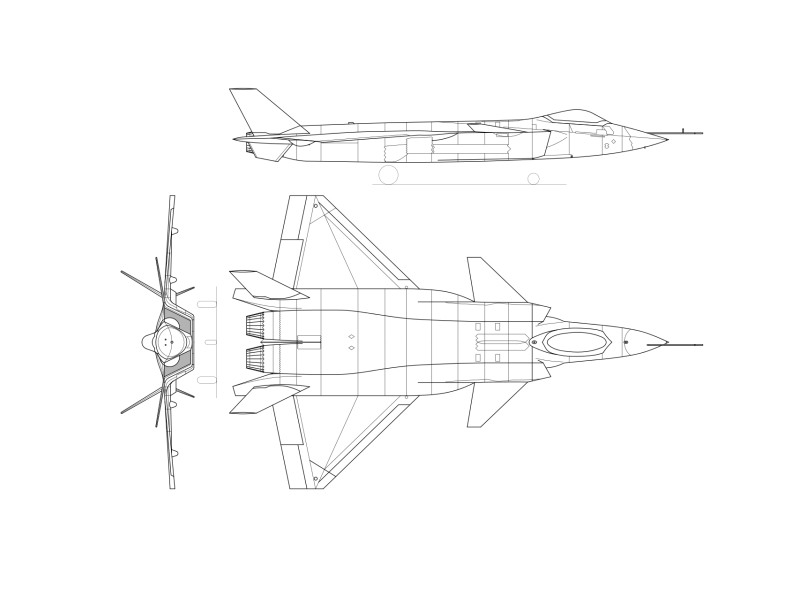

Image: Chengdu J-20

China has other designs undergoing development which would cement its airpower dominance in the region. A fifth-generation stealth fighter, the external pageChengdu J-20call_made, external pageis expected to be operational sometime between 2017 and 2019call_made. Only four prototypes currently exist and China has external pagereportedly encountered a number of significant technical challengescall_madein the development process, but the J-20 could in principle become a highly capable long-range strike system in the Asia-Pacific region. Less is known about the external pageShenyang J-31call_made, another fifth-generation stealth fighter reportedly in development. It is not yet known whether the J-31 would be land-based or carrier-based or in fact whether it is intended to be an entirely separate procurement project or if external pageShenyangcall_made and external pageChengducall_made were set up to compete with each other to provide one fifth-generation fighter model. Nonetheless, China is clearly striving to develop capabilities comparable to the external pageF-35 Lightning IIcall_made, far exceeding the airpower of other Asian countries.

That South Korea, Japan, and the members of the external pageAssociation of Southeast Asian Nationscall_made (ASEAN) are not rushing to purchase the F-35 or some other fifth-generation fighter is interesting and breaks with a trend seen in other frictious regions of the world. In the Middle East, the United Arab Emirates external pageis upgrading its air force with 60 Eurofighter Typhoonscall_made, external pageQatar will obtain 72 Dassault Rafale jetscall_made, and Saudi Arabia purchased 84 new F-15 fighters from the United States in 2011. The members of the external pageGulf Cooperation Councilcall_made have been rapidly expanding their airpower capabilities long before the collapse of external pageBashar al-Assad’scall_made regime in Syria and the rise of the so-called external pageIslamic Statecall_made. In contrast, the Islamic Republic of Iran is struggling to develop its own airpower capabilities. Unable to import aircraft, Iran’s most successful domestic weapons manufacturing project has external pageconsistedcall_made of the reverse engineering of the American-made external pageNorthrop F-5call_made. The resulting design, the external pageHESA Saeqehcall_made, is essentially a second-generation fighter, comparable to the bulk of the aircraft operated by Vietnam and the Philippines than to the state-of-the-art equipment employed by Iran’s Gulf neighbours.

This may seem an odd contrast. In the Middle East, the Gulf states are rushing to develop airpower capabilities despite already possessing a massive advantage over Iran. Meanwhile, in East Asia, the ASEAN member states seem undaunted by China’s air superiority. At first glance, it would seem more likely that ASEAN would be making large orders from Lockheed Martin and external pageDassaultcall_made while the Gulf Cooperation Council would be more cautious. However, the explanation from this discrepancy may lie in the historic power disparity between China and its neighbours. Even prior to the Chengdu J-20 and Shenyang J-31 development projects, China possessed a considerable arsenal of combat aircraft, while the air forces of other regional actors were almost non-existent. The only country which could be said to have anything approximating Chinese airpower in the late 20th century was Vietnam, which amassed a large number of MiG designs during the external pageVietnam Warcall_made and the subsequent external pageinvasion of Cambodiacall_made.

Image: Shenyang J-31

In this context, the rapid expansion of Southeast Asian air forces would upset an established power relationship in the region. China could regard the procurement of fifth-generation fighters by Vietnam and the Philippines as a threat to its security, further escalating tensions. Since Vietnam already possesses a submarine fleet that gives China pause, the acquisition of Sōryū-class vessels from Japan or other such maritime procurement projects does not upset regional security dynamics. Meanwhile, the rapid expansion of Gulf airpower is due to a lack of historical air superiority on the part of those countries. If Iran were to gradually close the capability gap, it could lead to increased risk of regional conflict, and so the Gulf states desire overwhelming air superiority as a deterrent.

Nonetheless, the rapidity with which China is attaining greater airpower capabilities should be of concern. PLAAF pilots are now attaining 100 to 150 flight hours per year. This is substantially less than the average among external pageNATO member statescall_made: for example, British pilots average 200 flight hours per year and French pilots generally reach 180 flight hours. China is seeking to best its neighbours in both the quality of its combat aircraft and its pilots. Although Chinese strategic planners continue to place heavier emphasis on the development of ground forces, neglecting airpower could create for the Southeast Asian countries too substantial a strategic vulnerability for China to pass up. In order to forestall such a scenario, it may be worthwhile for the United States and other concerned countries to step up joint training activities with the air forces of South Korea, Vietnam, the Philippines, and Indonesia. The pilots of ASEAN and other countries might not reach the same number of flight hours as PLAAF pilots, but the quality of the hands-on training with American pilots could go some way toward offsetting this, ensuring the Philippines gets the most out of its small contingent of FA-50 Golden Eagles in any potential confrontation with China. The sheer imbalance of the status quo demands action because of the nature of the dispute between China and its neighbours. Territorial aggression by the Gulf states against Iran would result in the mining of the external pageStrait of Hormuzcall_made and numerous other negative consequences. The external pageBasijcall_made, Iran’s extensive militia, could be just as powerful a deterrent as the Gulf states’ airpower. But PLAAF’s capacity to project power, if left unmatched, would make a smash-and-grab attack on disputed islands inexpensive indeed. The focus should be on raising the cost of such aggression.