The Geography of Boko Haram: More Deadly but More Remote

16 Feb 2015

By Davin O'Regan for ISN

Boko Haram’s brutal wave of attacks seemed unstoppable in 2014. Deaths from the Islamic extremist group’s campaign of violence in Nigeria external pagemore than doubledcall_made 2013’s toll, surpassing external pagerates seen during the recent conflicts in Iraq and Afghanistancall_made.surpassing levels of violence seen in Afghanistan and Iraq. The group overranexternal pagemilitarycall_made external pagebasescall_made and external pagecirculated footage of a Nigerian Air Force jet it claimed to have shot downcall_made. By August, Boko Haram announced an external page“Islamic State” in northern Nigeriacall_made, eliciting external pagecomparisons to ISIS’scall_madesweeping seizure of vast territory in Iraq and Syria. Some reports have claimed that Boko Haram controls up to external page20 percent of Nigerian territorycall_made.

An analysis of the geographic distribution of the group’s attacks and movement in recent years suggests more limited and shifting territorial ambitions, however. Despite Boko Haram’s growing lethality and external pagetactical sophisticationcall_made, the group appears to be concentrating larger proportions of its resources in Nigeria’s more remote border areas. This concentration, in turn, represents an opportunity to contain and isolate the group, though one that would require a coordinated security response that the Nigerian government and its neighbors have so far struggled to realize.

A contracting zone of conflict

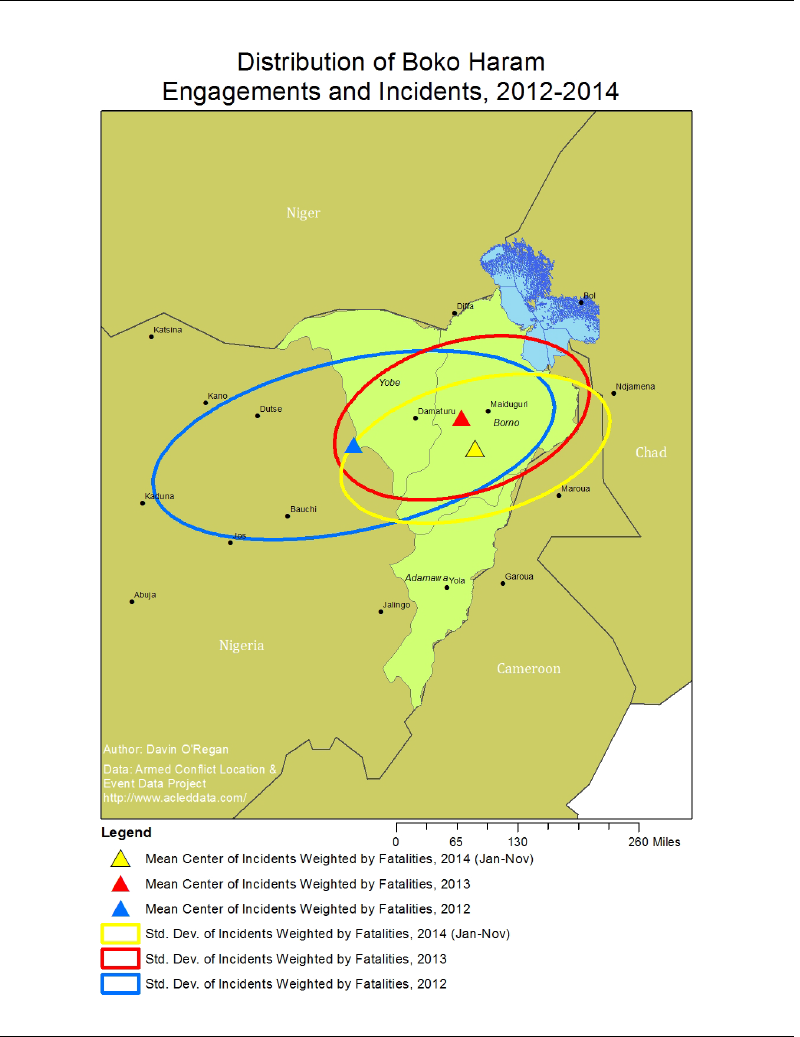

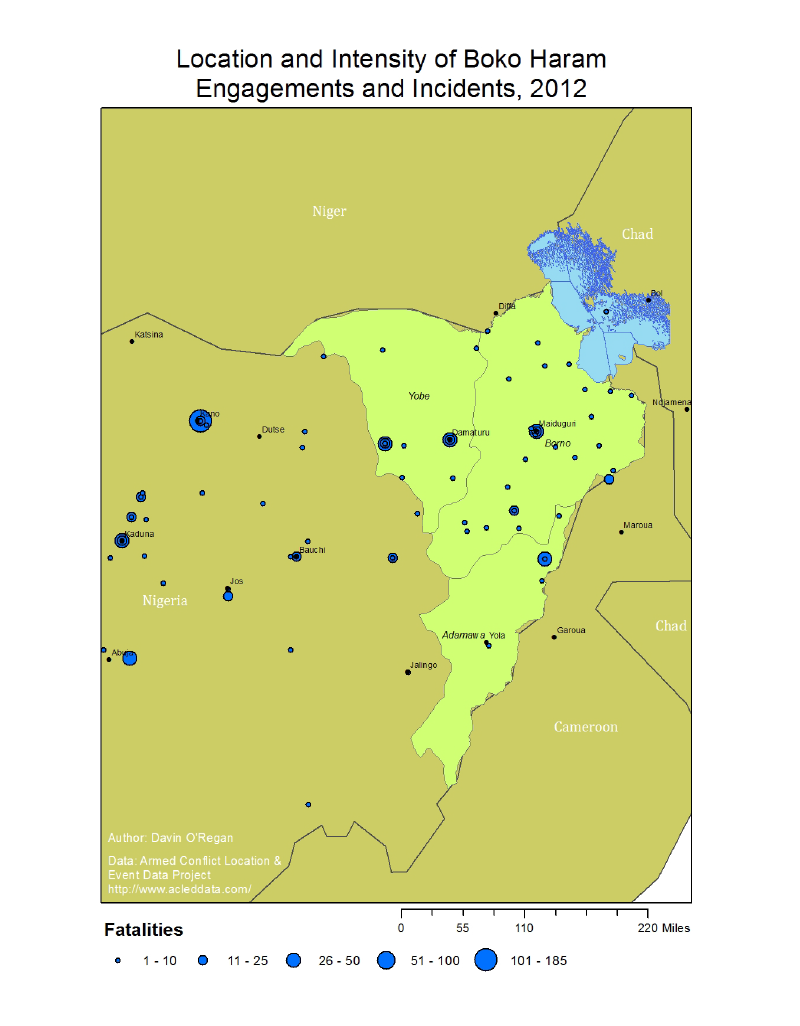

According to records from the external pageArmed Conflict Location and Event Data (ACLED)call_made project, in 2012 Boko Haram and its main splinter faction Ansaru operated over a wide stretch of Nigeria, conducting numerous attacks beyond Nigeria’s northeastern region, which has served as a hub for the group. The three northeast states of Yobe, Borno, and Adamawa have been under a external pagegovernment-mandated state of emergencycall_madesince May 2013 due to high levels of violence. However, in 2012 the geographic mean center of Boko Haram’s attacks – essentially their average latitudinal and longitudinal position weighted by number of fatalities – actually lay slightly west of Nigeria’s northeastern region (see maps below). Violent incidents typically occurred 220 miles from this mean point. About a third of the 269 incidents in 2012 – representing 40 percent of the fatalities for that year – were located outside the three states of emergency.

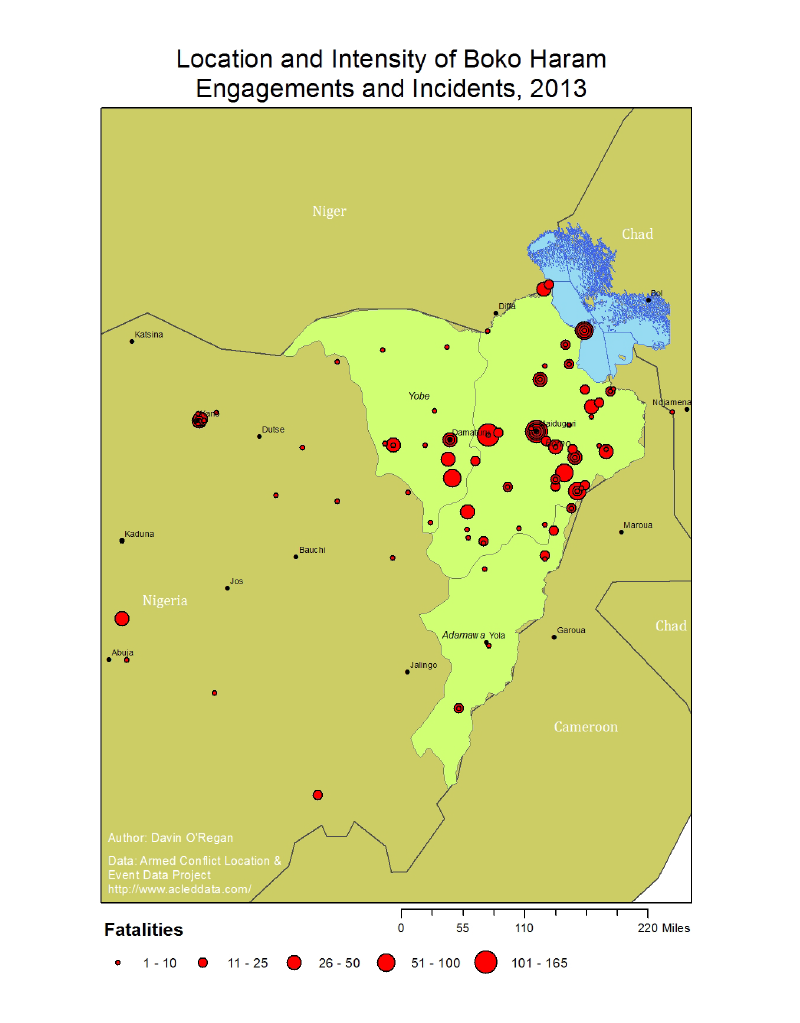

This pattern changed significantly in 2013. Of the 238 violent episodes that occurred in that calendar year, just 37 were located outside the three northeastern states accounting for just 10 percent of 2013’s total fatalities. The mean center of attacks in 2013 moved almost 130 miles eastward into central Borno, Nigeria’s most northeastern state. The average spread of attacks in 2013 also shrank by a third compared to 2012.

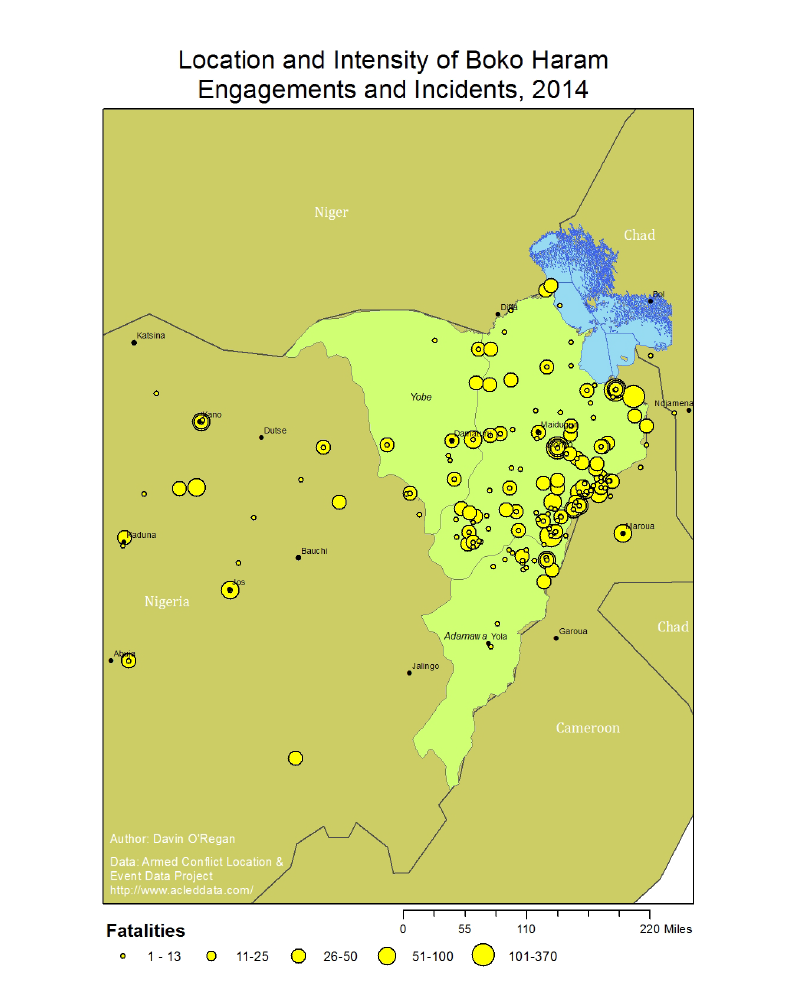

This more spatially concentrated distribution of violence has since held steady. The mean center of the 341 Boko Haram incidents and attacks in 2014 moved slightly eastward, closer to Nigeria’s border with Cameroon. Notably, it rests within just a few miles of the external pagetown of Chibok, where more than 300 girls were kidnapped by Boko Haram in April 2014call_made. The overall average spread of incidents in 2014 was roughly the same as in 2013.

But other more subtle differences distinguish the geographic patterns of Boko Haram violence in 2013 and 2014. Attacks in 2014 were clustered along the border between Nigeria and Cameroon. About 56 percent of all Boko Haram attacks and fatalities in 2014 occurred within 50 or fewer miles of this border, an increase from 40 percent in 2013. Similarly, in 2013 there were 43 Boko Haram attacks featuring 648 fatalities in Maiduguri, the capital of Borno State located about 100 miles from the border from Cameroon, yet there were just 10 attacks and 164 fatalities in the city in 2014.

The tri-border region where Adamawa and Borno States meet Cameroon experienced especially high levels of violence. Roughly a third of all attacks and all fatalities in 2014 took place within 50 miles of the Borno-Adamawa border with high concentrations near Cameroon. Many of the towns and villages along the border areas experienced repeated attacks throughout 2014, suggesting Boko Haram’s hold over some of these border areas is not entirely firm.

Types of targets and engagements also shifted between 2013 and 2014. Whereas the group was as likely to attack civilians in 2013 as it was to engage in battles with Nigerian security forces, in 2014 about 54 percent of all incidents of violence were attacks on civilians while just 39 percent were exchanges with the military and police.

To be clear, these figures reflect only general trends and geographic distributions. There were several large bombings in 2014 that featured dozens or hundreds of deaths in Kano, Jos, and Abuja, far from Nigeria’s northeast. But the group appears to be concentrating a relatively larger proportion of its wherewithal and energy on a smaller and more remote border area.

An intentional shift?

Why has Boko Haram concentrated its efforts along the eastern border? Or, more specifically, has it been pushed eastward or has the group chosen to focus there?

Unfortunately, the Nigerian government’s response to the violence has had only minimal effects. For several years Nigeria hasexternal pagemaintainedcall_made aexternal pagesizable deploymentcall_made of external pagesecurity forcescall_made in the northeast to combat the group. However, troops have often retreated from Boko Haram attacks, including from their own external pagebases and garrisonscall_made. But the official effort has been hobbled by surprising external pagelevels of mismanagement, indiscipline, and human rights abuses in the armed forcescall_made, especially given external pageNigeria’s performancecall_made during past peacekeeping and combat operations. The campaign has generated significant blowback. Out of deep frustration with the provision of limited and often unusable arms and supplies, Nigerian external pagetroops have even mutinied and fired on senior officerscall_made. Some have reportedly external pagecooperated with Boko Haramcall_made out of shared antipathy for the government. Overall, Nigeria’s military operations have achieved only marginal effects – perhaps occasionally counterproductive ones – on Boko Haram’s movements and operations.

The emergence in 2013 of several sizable external pageinformal civilian militiascall_madein population centers such as Maiduguri, the capital of Borno State, has provided some defensive gains against Boko Haram. With better knowledge of the local population and terrain, these dedicated groups have been able to more effectively prevent and repel some Boko Haram attacks. However, lacking oversight and discipline, they have also been linked to extensive human rights abuses, external pagegenerating other serious security challenges and local disputescall_made. Nor are the civilian militias particularly mobile. In general, they rarely pursue or engage Boko Haram offensively.

There are few indications that current efforts are effectively putting pressure on Boko Haram. Rather, the contraction of Boko Haram’s reach and its shift eastward into Nigeria’s border regions may reflect an intentional decision. Unsatisfied with a strategy of widespread terrorist attacks in 2012, perhaps the group has progressively shifted focus to closer and more accessible targets in the northeast.

While Boko Haram continues to orchestrate deadly bombings in distant cities such as Kano and launch attacks on military positions, on average it seems to prefer repeated attacks on lightly guarded remote towns where it can destroy homes and kill unarmed civilians or seize comparatively understaffed security posts. Border regions may hold particular appeal. Boko Haram can easily launch attacks and retreat across jurisdictional boundaries that security forces are often unable or disinclined to cross.

In other words, Boko Haram has recently been opting for low-hanging fruit over more ambitious targets. While the body count from the group’s more frequent attacks continues to increase, these numbers are driven by a growing focus on peripheral civilian targets, suggesting the group is less preponderant than is often described.

An opportunity for containment

If correct, this shift towards the border may offer an opportunity in the short-term to contain the further expansion of violence in the region and erode Boko Haram’s capacity. But a significant long-term challenge looms if this opening is not seized.

The border with Cameroon is critical. A stronger deployment of security forces in key areas along the frontier zone may lower the incidence of attacks on civilians and lead to more occasions to engage and weaken Boko Haram units. This would require tight security coordination with Nigeria’s neighbors to encircle Boko Haram, thereby limiting the group’s mobility and the benefits it realizes from operating across borders. It must also balance a population-centric deployment in which military units remain in high-population border areas to defend against attacks on civilians with mobile support units that can respond quickly to intelligence and Boko Haram maneuvers.

Nigeria, Cameroon, Chad, and Niger, all of which have experienced Boko Haram attacks, have in the past agreed to pool their resources and collaborate against the group, most notably by establishing a “multinational” military base near Lake Chad in November 2014. However, external pagethe base was run almost entirely by Nigerian forces and seizedcall_made during a Boko Haram attack in January 2015. Collaborative efforts will need to be greatly improved to permit joint operations against Boko Haram from multiple flanks. Recent announcement of external pagean African Union security forcecall_made of 7,500 troops to be deployed against Boko Haram followed by several successful offensives by Cameroon, Chad, and Nigeria may help catalyze such coordination.

This opportunity to contain Boko Haram may prove temporary. Since 2012, the group has increasingly focused its energies on comparatively small towns and villages along the Nigerian-Cameroonian border, but by doing so it is slowly encircling Maiduguri, the largest city in the northeast. Eventually, the group will be able to attack the city from multiple vantage points, providing it a huge operational advantage against the city’s defenses. A stronger and more coordinated counter-insurgency effort along Nigeria’s border would split the horseshoe shaped area of operations that Boko Haram has focused on in 2013 and 2014.

Of course, the conflict in Nigeria’s northeast is complex. Boko Haram was born of and is driven by a broad range of factors, including significantexternal pagesocioeconomic inequalitiescall_made and a variety of long-running external pagepolitical grievancescall_made in Nigeria’s north and northeast. Military operations will not resolve these deep and complicated conflict drivers.

Yet a more concerted and assertive security effort along Nigeria’s borders would drive at the heart of Boko Haram’s strategy. The group has not become the unshakable force that its gruesome 2014 death toll at first suggests. The conflict’s booming casualty rate is a product primarily of the group’s increasing exploitation of remote and weakly guarded border areas, not necessarily its operational dominance. A stronger and more regionally coordinated counter-insurgency response along Nigeria’s northeast frontiers could reverse this advantage and spare the region another year of tragically high civilian deaths.

Maps (click to enlarge)

Distribution of Boko Haram engagements and incidents 2012-14

Location and intensity of Boko Haram engagements and incidents 2014

Location and intensity of Boko Haram engagements and incidents 2013

Location and intensity of Boko Haram engagements and incidents 2012

These maps, including a full explanation of the sources and methodology used to produce them, areavailable for download in the ISN Digital Library.