Putin’s Russia: Exploiting the Weaknesses of Liberal Europe

31 Mar 2015

By Jonas Grätz for Center for Security Studies (CSS)

This chapter of Strategic Trends 2015 can also be accessed here.

Russia’s aggression against Ukraine has brought war back into Europe. In addition, it presents a threefold challenge to an already weakened liberal Europe: With regard to security, Moscow has spoiled the EU’s approach of transforming its neighborhood while disregarding the power of military coercion. Furthermore, Russia’s President Vladimir Putin can also exploit the existing weaknesses of the EU’s economic policies and the waning enthusiasm for the EU’s liberalism in member states. Collectively, those challenges result in a crisis of the EU’s liberal order.

In the run-up to 2014, Europe was preparing to commemorate the start of the First World War. The overwhelming mood was one of a chastened look back on a very different past that Europe has long left behind. One year later, Russia has annexed Crimea, robbing a piece of land from a post-Soviet country. Even more strikingly, it keeps fuelling a war that has killed thousands on the battlefields of Donbas. As events in Ukraine mirror broader disagreements between Russia and the West over the perception and the future of the European interstate order, fears of further military escalation have been revived.

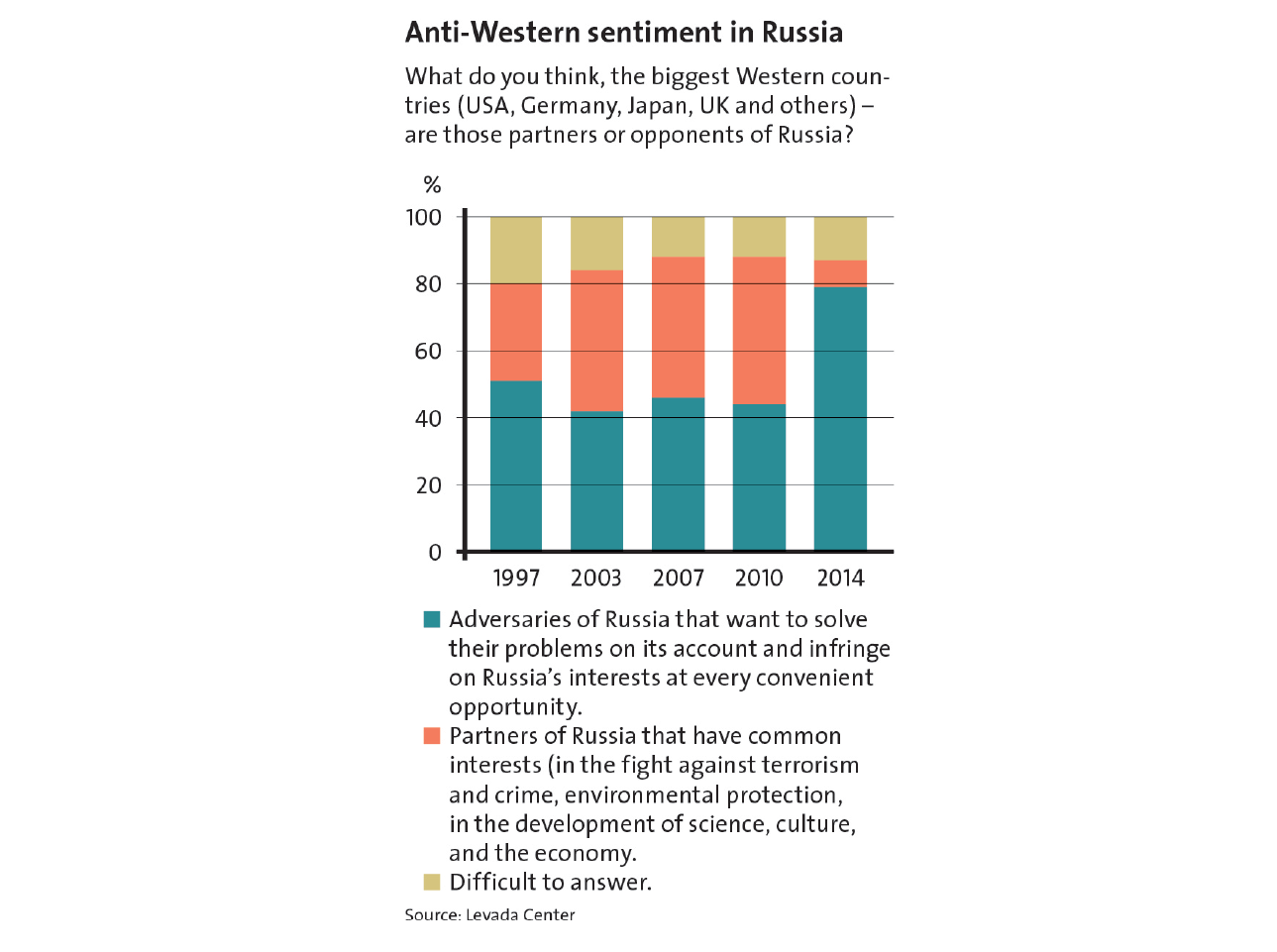

The conflict eludes any consensus of the two sides. The EU emphasizes that Russia’s actions have undermined the core principles of the European security order such as the 1975 Helsinki Final Act and the 1990 Paris Charter that had stabilized peace since 1975 and had settled the Cold War. Moscow believes that these rules have become outdated as they do not reflect Russia’s position as a great power but instead helped to spread Western institutions, such as the EU and NATO. Thus, where the EU argues that sovereign states are free to join alliances, Russia sees a threat to its own survival as a great power, engineered by the EU and the US. Hence, Russia’s main aim is to devise new rules and principles that would prevent Western structures from coming even closer to the homeland. To achieve this, Putin is eager to weaken Western institutions and to benefit from any emerging split between Western European nations as well as between them and their transatlantic partners.

The central argument of this chapter is that the EU’s liberal order is in crisis, as existing weaknesses are being exploited by Putin’s Russia. Moscow is confronting an EU that is militarily unprepared; it aims at exploiting the EU’s growing economic divergences, and it is deliberately targeting an already fraying domestic political consensus. This constitutes a threefold challenge in the spheres of security, economy, and political ideology.

Liberalism, with its focus on individual autonomy and rights as constituting principles of order, has been the blueprint of the EU’s integration model. It has allowed the EU to become a forward-looking project that aims to overcome historic and geographic determinism. By crafting common rules, the European world would become less discrete and more ‘flat’ and accessible to individual activity. Europe would not have a common past, but a common future. This vision is challenged by Putin’s traditionalist revisionism, by the failure to overcome economic crisis, and by the resulting return of the nation inside the EU.

With regard to security both sides have strikingly different perspectives on international relations, and there is no agreement over principles. Thus, while the security situation in Europe may not be militarily as threatening, it is nonetheless more volatile than during much of the Cold War. The EU has so far failed to improve its military capabilities, remaining a soft power in a more and more ‘hard-power’ world. It is thus liable to continue in the shadow of NATO for the years ahead. This, however, enables Putin to target the transatlantic link and stir underlying anti-American sentiments.

Economically, liberal economic integration has failed to bring about the necessary political convergence, as highlighted by the persistent Euro crisis. Economic imbalances have been strengthened between and within countries, giving rise to envy, resentment, and disenchantment with integration. As Germany has emerged as an economic powerhouse, effectively bankrolling other European countries, the old problem of German power in Europe has resurfaced. European integration and the Euro were conceived to hold the specter of German domination at bay. Germany’s strong position is therefore grist to the mill of those who think of the EU in terms of power politics rather than in institutions. This both encourages and justifies strategies of bandwagoning with Moscow, undermining the EU’s unity.

Politically, a chauvinist and illiberal alternative to mainstream and pro- EU parties has arisen on the back of economic problems. Playing on resentment against a ‘German Europe’ and the US, they oppose the EU’s most important institutions, such as the Euro and the free movement of people and services, instead seeking salvation in a Europe of sovereign, self-sufficient nations. Needless to say, these parties stance enjoys Putin’s monetary and ideational support. Similarly, they see Russia as a partner for a future European order, based on nation-states. This limits the EU’s space of maneuver towards Russia and poses questions over the durability of the EU and its commitment to liberal order.

This chapter will focus on how Russia has exacerbated both of the EU’s crises, external and internal, and how the EU has reacted to these challenges. It will therefore first outline why Putin’s Russia, as a ‘postmodern absolutist state’, presents an existential threat to the EU. Second, it will look into the crisis of Europe’s external security, of its economic principles, and of its political ideologies, which in turn prove to be open doors to be exploited by a determined Russia. Third, in conclusion, it will take a look at what this might mean for the years ahead.

A systemic challenge: Russia’s postmodern absolutism

As indicated in last year’s Strategic Trends, the Russia that annexed Crimea poses a distinct systemic challenge to the EU. To understand Russia’s actions, it is not appropriate to focus on theories of great-power competition. Russia’s behavior is governed by the country’s domestic order and associated constraints rather than the laws of international relations.

Russia’s order today can best be understood as a form of postmodern absolutism. It combines absolutism’s traditional elements – a single ruler with a strong coercive capacity, a belligerent army, a subservient economic class, mercantilist economic policy, and a subservient church – with the postmodern notion that reality can be constructed in the mass media. With the help of communication technology, the absolute ruler can construct his or her own reality in order to maintain power. Hence, postmodern absolutism relies less on coercion of the masses than on their manipulation. Also, Orthodox faith is only one source of legitimacy; while Russia is being positioned as a traditionalist, anti-Western great power in order to legitimate the regime.

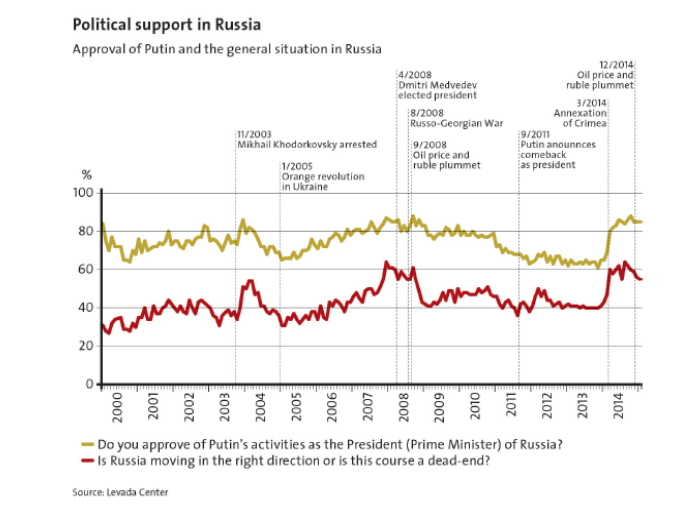

Postmodern absolutism works for Putin, as Russians despise the authorities, yet overwhelmingly believe that their country is a great power that has to be supported at any rate. Hence, Putin can muster support from the population as long as he can present himself as defender of a Russia that is great, but under threat. A great Russia must never show weakness. Putin’s weakness would become evident if he tried to reform the economy. His re-ideologization is thus defensive and experimental; he is acting out of anxiety rather than out of strength.

Popularity is Putin’s main focus, and it hinges on showing strength. This also implies that his actions will depend on the resistance he encounters. To remain in power, Putin therefore has two main tasks. For one, he has to nurture the basic foundations of Russia’s identity as a traditional great power. It would be shattered if Ukraine or other neighbors with close ethnic and historical ties adopted a Western trajectory. Second, Putin must constantly prove that Russia is a great power. Hence, he increased funding for the military. Also, he founded the Eurasian Economic Union in his effort to talk with the EU on equal terms. In Ukraine, both of these tasks converge: It is the most vital neighbor for Russia’s great power identity and is engaged with the rival EU. If Ukraine adopted a different path, the underlying narrative and the potential to shore up power vis-à-vis the EU would be in tatters. It is these tasks of ensuring regime security that dominate Putin’s policies, rather than abstract notions of ‘national security interests’. But Putin’s dependence on popularity also means that there are limits to his actions. Two factors have made Putin hesitate in Ukraine. First, the appetite for conducting war is checked by the risk of casualties. So far, these have been limited as Putin has been able to arm volunteers from Donbas, Russia, and elsewhere. However, a broader war would necessitate greater involvement, which would have an impact on Putin’s rating. Wanting to believe in propaganda is one thing, especially if it is favorable to one’s own cause, but should he decide to sacrifice the lives of thousands of Russian sons and husbands, a different propaganda effort would be necessary. Another weakness is the economy: Economic decline will over time reduce the resources that Putin can bring to bear – both internally and, crucially, also to prove Russia’s capabilities as a great power. Therefore, were the conflict only about Ukraine, the challenge to the EU would not be existential; however, as is argued below, it goes well beyond the Donbas.

The roots of the conflict in Ukraine run deep – at the fundamental level, it is also a systemic conflict between the antagonistic political orders of a liberal EU and Russia’s postmodern absolutism. The orders produce different fears: EU leaders fear nothing more than military conflict, and Putin fears nothing more than the breakdown of his regime. On the contrary, Putin’s Russia has proven to have a higher tolerance for war, obviously accepting physical coercion as a substantive element of power. This is why he has the upper hand over the EU as long as he can extract concessions by waging a limited war.

Security: the military’s power to frustrate

Putin’s embrace of postmodern absolutism has led to conflict with the EU. Not limited to Ukraine, this struggle presents the first real challenge in decades to the security of EU members as well as to its ‘soft security’ focused external policies. Worse still, the conflict in Ukraine came unexpected: The EU was lulled by its transformative success in Eastern Europe and on the Balkans, assuming an apparent liberal consensus where there was none. Meanwhile, Europe seems to have lost the ability for strategic, politico-military thinking that prevailed during the Cold War. The EU has now been forced to acknowledge that it needs a credible ‘stick’ to complement the economic ‘carrots’ of its liberal agenda.

A hard landing for the ‘soft’ neighborhood policy

Traditionally, the EU’s policy towards its eastern neighborhood has been stimulated by the more or less successful waves of enlargement. But while it was strong on its ambition to transform new members and extend the liberal order to further regions, its key flaws have always been a lack of resources and incentives. This ambiguity reflected policy disagreements in the EU: Whereas some members, such as Poland and Sweden, were strongly in favor of a robust policy or even offering membership to Ukraine, continental Western Europe had largely succumbed to ‘enlargement fatigue’, whereas Southern Europe was essentially indifferent.

It was only after Russia’s war against Georgia in 2008 that the EU decided to shift up a gear. The argument was that the countries left in between Russia and the EU should be given more attention in order to reduce Russian leverage. Hence, the EU negotiated ambitious association agreements that would help those countries to transform into liberal market economies. However, the EU still wanted to offer those countries an alternative to Russia on the cheap: enlargement fatigue prevailed – the agreements did not provide for the free movement and settlement of people. Fear of work migration and competitive pressure were among the main reasons why the EU still did not hold out any membership perspective.

Matters of hard security went totally unheeded, leading to a grave miscalculation. Some even thought that the EU offer would be the catch-all solution to regional problems: Purportedly, it would not be seen as a threat by Russia, unlike NATO, while it would assuage the states to the east. Nevertheless, hard security soon came to trump the EU’s offers: Those partner countries dependent on Russian security guarantees, such as Armenia, had to cease cooperation.

When Putin turned to Ukraine and annexed Crimea, the EU was supportive of Kyiv, but still loath to confront Russia directly. Economic interests are strong for many members, as is Russia’s outsized diplomatic role in many of the world’s arenas. Even more important was the general desire for friendly relations with Moscow in many corners of the EU. This is joined by considerations of power politics in some small EU countries that see Moscow as a partner to balance against an EU dominated by large states.

It is notable that even the Visegrad states of Central Eastern Europe were not coherent: Warsaw was hawkish, whereas Prague, Bratislava, and Budapest joined Western Europe in prioritizing the economy. Initial sanctions were symbolic as a result, mostly targeting political relations and individuals. More ‘hawkish’ EU members, mostly Poland, Sweden, and the Baltics, were placated with a three-stage plan to eventually escalate sanctions.

It took the Kremlin’s excalation in the Donbas to galvanize the EU. The decisive catalyst came on 17 July 2014, when what were probably Russian forces accidentally shot down Malaysian Airlines Flight 17 with a BUK anti-aircraft missile. Now, Germany came around in support for sanctions and took the lead in coordination. This was supported by the UK, the Netherlands, and eventually France. The smaller dissenting states could no longer resist the general trend. At last, the EU was ready to impose financial restrictions against selected banks and companies, as well as export restrictions for military, dual-use, and certain energy extraction technologies.

The EU’s growing firmness, joined by a tanking oil price, did not go unnoticed with Putin. Firstly, while his goals remain unchanged, he went back to the negotiation table to agree on the Minsk protocol in September 2014. As this did not end the fighting, Putin limited himself to a comparatively light footprint in Donbas and concentrated on destabilizing Ukraine rather than on a full-fledged assault. Secondly, the worsening economic outlook in Russia has reduced Putin’s resources at home and abroad, even though the population has so far rallied behind the leader. Disillusionment among the middle class and the elite may grow over time, making Putin more amenable to negotiations with the West over kick-starting his economy.

However, in February 2015, Putin again sensed an opportunity. Some of the sanctions were soon to expire, and the EU’s internal political crisis was bleeding into foreign policy: Elections in Greece had added a firm voice of resistance to renewing, let alone thinking of further sanctions. Thus, a new ground offensive by the separatists was again supported with the latest Russian equipment. Putin’s basic logic continues to produce results: Every day the war continues, Ukraine grows weaker as a state and the EU loses out on establishing a workable regional order.

Hard security: Washington, the savior?

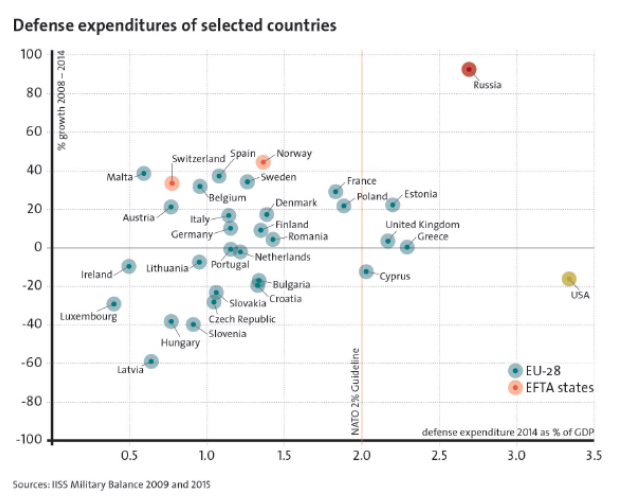

Under any scenario – continuing with a liberal neighborhood policy or accepting Russia as a great power in Europe – the EU’s member states would need strong military forces. However, the EU’s military power is weakening in the wake of economic crisis. To be sure, the conflict has brought hard lessons with regard to the continued utility of military force, but these have not, as of now, translated into a higher commitment to military affairs. Even after the events in Ukraine, most EU members are still reluctant to increase their below-norm defense budgets.

This has only added to the EU’s traditional ‘Venus’ character: Attempts at making the EU a full-fledged security actor have fallen flat. The European Security Strategy dates from 2003. Military cooperation between EU members has been affected as well: Franco-British cooperation, the most ambitious partnership, is lingering due to budgetary constraints and conflicting political agendas. Only small members such as Sweden and Finland are trying to build up closer military ties. As a result, after years of trying to build a common European defense capability, NATO and thus the US are still the main guarantors of European security. This trend has only been reinforced by the Ukraine crisis – not so much because the US wanted to, but rather because many EU leaders do not have many viable alternatives. Facing the choice between a well-known US role as security provider and Russia’s preference, a ‘multipolar world order’ with its inherent instability, many naturally opted for the former.

However, doubts remain whether the underlying premise of the renewed pivot to the US is credible, which might reinforce instability. The priority that the US attaches to European defense is uncertain, given the Pentagon’s already stretched commitments, turmoil in the Middle East, and Washington’s increasing strategic introspection. Nerves are frayed in Eastern Europe, and Putin may be tempted to test the US commitment to those countries. In any case, the outsized role ascribed to the US in the defense of a majority of EU members allows Russia to conveniently equate the EU with NATO and the US, which provides fuel to a regional conflict and pushes it right up to the global level, elevating the stakes. It also adds fuel to Russia’s propaganda machine in the EU, where many are made to believe that the EU is being dragged into a conflict that is in Washington’s interest.

On balance, the EU’s security is in a dangerous limbo. If the EU wants to uphold its liberal order, it either needs unambiguous assurances from the US about its future long-term commitment, or it must start investing into a higher military profile itself. If things continue as before, the low profile of NATO’s European members and the uncertain US outlook might well invite Russia to test the commitment of major EU member states and of the US to defending Eastern Europe and the Baltics.

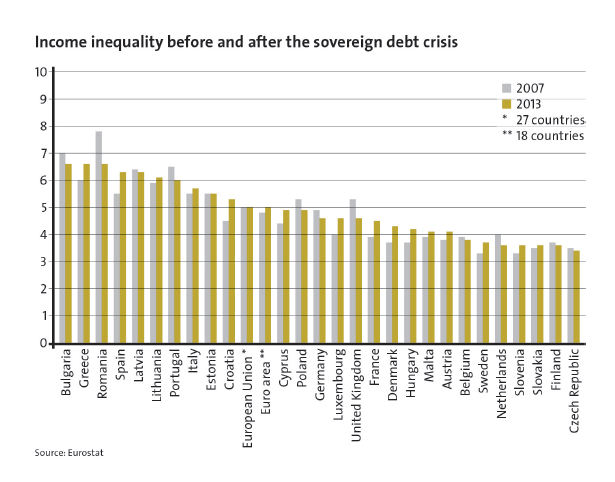

Economy: dividing the EU

While Putin’s Russia faces the EU from outside, its economy is a challenge coming from within. Having started as an economic project, the EU might also fall due to economics – most vividly expressed in the continuing crisis of the Euro, which is weighed down by heavy public debt burdens. The lagging growth is only a syndrome, however. More severe for the political coherence of the EU are the growing divergences between EU member states. Those, in turn, are driven by the underlying political blockades that have been further deepened by the crisis response policies. These policies and their economic effects have undermined the EU’s legitimacy in the eyes of large parts of the European population. The lack of economic performance also supplies additional arguments to those that look towards Moscow as an alternative to Brussels.

The EU’s crisis response: fuelling realism

When the Euro crisis hit in 2008, not many countries were keen to take a lead: France had a high debt load and rising unemployment rate itself. Italy was hit hard by the crisis. The role of crisis manager thus fell to Germany. Germany was ready to provide the EU’s financial assistance with the necessary firepower, but together with its northern partners, it demanded strict reforms and spending cuts in return. Five years on, unemployment and poverty have declined to a long-term low in Germany, while the opposite has happened in Southern EU countries, especially in Greece. This has undermined the trust in the EU.

Worse still, the crisis response policies, while technically and morally justified, were in part self-defeating. They had a counterproductive effect on the ability of the periphery to reform: Contributing to higher inequality, they undermined societal readiness to accept reform. Instead, they fuelled fears of social decline and mistrust of elites. As argued below, this has given rise to radical right- and left-wing alternatives.

The EU’s concrete policies contributing to these trends were the bank bailouts, austerity, and quantitative easing. First, bank bailouts were designed in a way that emphasized the responsibility of states and discounted the responsibility of creditors. Hence, taxpayers in the EU and especially the crisis states were held responsible, while the financial system and its decision-makers were saved. Only in the case of Greece did private creditors have to accept a ‘voluntary haircut’ – equal to only one eighth of total Greek debt. While there might have been good systemic reasons to bail out the banks, this policy was the ‘original sin’ of crisis response with long-term distributional consequences. This precedent can also be used to agitate against the EU as representing the interests of financial markets.

Second, the austerity policies that have been negotiated by the Troika of the EU, the International Monetary Fund (IMF), and the European Central Bank (ECB) foresee a radical reduction of expenses and structural reforms to put the state budget on a positive long-term trajectory. Usually quite heavy on the expenditure side, these programs again tend to impact mainly the middle classes and the poor rather than the rich, amplifying the effects of the economic crisis. This is all the truer as the rich successfully exercised their power to avoid accountability in crisis-ridden states – which is an issue wholly, unrelated to the Troika policies. For example, it is estimated that wealthy Greeks hold the equivalent of 65 per cent of their country’s GDP in assets abroad.

Third, the ECB’s quantitative easing is a concession to periphery states. It was not officially supported by Germany and is intended to somewhat reduce the impression of German domination of the EU. The ECB’s main trick is to buy government bonds so that their yield stays low, regardless of the risk perceived by market actors. The economic results are excess liquidity and ultra-low or negative interest rates. The latter penalize savers and future pensioners – again, the middle class. Excess liquidity has to be invested somewhere, which elevates asset prices. Hence, stock and property owners profit. The only positive effect for the poor may be in terms of investment and employment rising due to a weakened currency, but investment has not been boosted so far.

The EU thus finds itself in a vicious circle. Countries have to improve competitiveness, but the EU’s policy responses to the crisis have further worsened the societal foundations needed to achieve it. To be sure, local elites are also to blame. But the policies followed by the EU under German leadership have constituted a useful target for those who prefer to view the EU as an imperial project, weakening its coherence.

Putin’s economic attraction

With the EU in a profound economic and institutional bind, and helped by the growing divergences, Putin’s Russia holds considerable attraction as a partner for trading and balancing against German influence. This has already weakened the resolve of the EU when it comes to sanctions. It also bolsters those who want to sacrifice the existing European order for the sake of profits.

To be sure, the crisis in Ukraine and the falling oil price have somewhat weakened Russia’s economic soft power for the time being. The South Stream gas pipeline, Russia’s main project in the EU, is an obvious casualty of the conflict. With this pipeline, Russia planned to divide and rule by attracting the Balkans and Central European countries economically. But the financial sanctions and the worsening outlook for Russia’s Gazprom have killed the project.

Nevertheless, Putin has not given up on his game of ‘divide and rule’: Now, he is trying to capitalize on the new government in Athens, choosing Greece as the new end point of the proposed gas pipeline to Turkey. The tactic is always the same: Promising construction contracts and transit revenues, Russia lures its partners to toe a pro-Russian line in the EU, be it with regard to foreign policy or energy laws.

While the EU’s sanctions and Russia’s counter-sanctions did not have a large impact on overall growth, they do impact local economies. The reduction of economic cooperation with Russia is an easy target for those forces critical of the EU. The sanctions thus add to the prevalent criticism of the EU’s economic policies. The rise of alternative elites and their non-mainstream parties is now driving this point home – with a little help from Putin.

Politics and Putin: ideological subversion

The economic crisis with its growing imbalance between EU countries has led to a political backlash against the EU and the liberal ideology it stands for. As liberalism puts the individual with its freedom and rights in the center, it breaks down traditional communities and identities that act as stabilizers. This tends to be compensated if liberal markets are perceived to bring overall benefits, as individuals adopt a positive, progressive outlook on the future. If markets do not deliver enough benefits, however, the balance tilts against liberalism: Fear of decline and distrust of elites results in renewed calls for community.

As the EU has never been able to foster a ‘thick’ identity with redistributive institutions, this call is directed at the nation-state. As a result, demands are heard for ‘real’ national elites that will reinstate borders and protect the nation instead of following the demands of global markets. The EU is being hit twice: Both as a liberal project that has been advocating the completion of the internal market since the Maastricht treaty, and as a supranational institution, because demands for national sovereignty do not mix well with the spirit needed to make common institutions work. This feebleness of the EU’s ideology is again being exploited by Putin’s Russia.

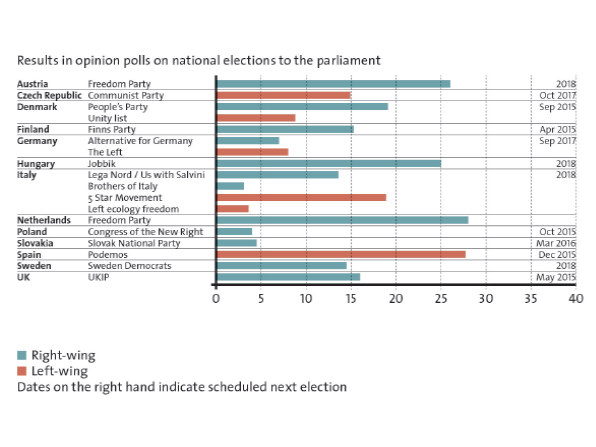

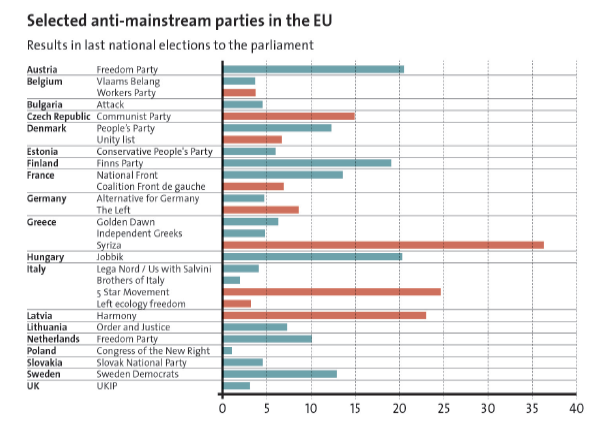

The rise of anti-mainstream parties

The EU’s party landscape is witnessing a rapid transformation. Anti-mainstream parties from the right and left are rising, and they are forming new lateral partnerships on an illiberal and social axis. In Northern Europe, far-right nationalism is on the rise, which is often directly opposed to EU membership. In Southern Europe, where austerity is the defining feature of life, nationalist left-wing parties are more prominent. All of them promise a return of politics, ‘real change’ instead of the endless administration of political life under current governments. As the Syriza-ANEL coalition government in Greece illustrates, there is not much enmity between left and right. While they disagree on identity politics and chauvinism, both agree on their state-centric and social agenda, as well as their staunch opposition to the US and the EU.

Far-right nationalist parties react to the fears of solitary economic decline. Taking their cue from Putin, they seek to revitalize the community of the nation with its traditions as a source of inspiration and mobilization. Muslim immigrants are often the main target, while the EU is a secondary target limiting national autonomy. Far-right nationalists are now the third-largest force in France, the Netherlands, Austria, Greece, Denmark, Finland, and Sweden. In the UK, France, and Denmark, they won the 2014 elections to the European Parliament, EP, while the ‘Alternative for Germany’ came fifth. Those parties either want to leave the Schengen Agreement, the Euro zone, and the EU, or substantially renegotiate existing treaties so as to minimize the impact of transnational cooperation to the bare minimum level, for example, to fight crime. To make the renovated national home more comfortable, most of them vow to invest strongly in social protection of the elderly.

In Southern Europe, which is suffering from austerity and a profound malfunctioning of its state institutions and elites, more ‘progressive’ causes are taking root. Some parties, like comedian Beppe Grillo’s ‘Five Star Movement’ in Italy, which came in second in both national and EP elections, rally against the mistrusted institutions of representative democracy, but do not have an elaborate ideology that would let them take up the key questions. Grillo’s success is not likely to last.

More traditional left-wing parties rallying for a strong welfare state and against the ‘austerity diktat’ are likely to have a more profound impact. The landslide victory of Alexis Tsipras’s Syriza in the 2015 Greek elections will have repercussions in Spain and Italy. The concessions that he will be able to extract will also be demanded elsewhere. In Spain, the leftist Podemos movement draws heavily on Tsipras’s experience and is now the most popular party, having come fourth in the EP elections.

Interestingly, strong anti-systemic parties are not easy to be found in the new EU member states of Central Eastern Europe. For one, the economic crisis has hit them less severely or has been overcome quicker due to the better societal cohesion. Secondly, Muslim immigration is not an issue in these societies. Third, the mainstream parties have traditionally been more inclusive of Eurosceptic attitudes and social conservative values. Hungary, where radical ethno-nationalist and anti-Semitic Jobbik party is the third-largest political force, is an exception.

Putin: investing in a new Europe

For Putin, these new anti-mainstream parties represent a huge opening in his effort to undermine the EU. They are exactly the force that he needs for realizing his goals: They are mostly opposed to the US and NATO, while advocating stronger ties with Russia. In most cases, they also want to dismantle the EU, striving for a Europe of self-sufficient sovereign nation states instead of rules-based integration. Ideologically, they are on the same line, emphasizing at least resistance to global capital and at most adherence to the same traditional values. This would allow Russia to re-emerge as a great power with its own sphere of influence, and to wield greater influence in Europe. Even if such parties do not come to power, they will lead to a more cautious approach in the EU too, as they will be a credible threat to existing elites.

The love is reciprocal – most of the alternative elites to the right and left of the spectrum exhibit sympathies for Putin’s Russia. For one, they see him as a truly sovereign ruler who has resisted the anti-political forces of an US-dominated global market. Ideationally, they are fond of him for cherishing national traditions over liberalism and multiculturalism. Thus, for many alternative elites, Putin is coming to the rescue as the white knight in their ‘anti-imperialist’ fight against the US-based Western order and its ‘lackeys’ in Brussels.

Putin’s support for anti-mainstream parties comes in three ways: informational, organizational, and financial. Informationally, the parties profit from Putin’s propaganda networks such as the TV station RT. They grant extended coverage to the party leaders and their views, as well as portraying key common enemies, such as the US and global capital, in a negative way. Organizationally, the Russian ruling party United Russia has developed strong ties to many of the anti-mainstream parties and sends members to their party congresses. The party leaders are also regular participants in Russia-based political conferences, discussing possible layouts of an alternative Europe. Financially, the EUR 9 million loan of the Russian-owned First Czech-Russian Bank to the French Front National stands out.

The Ukraine crisis and the unity that European leaders have shown over the war in Ukraine have further alienated the inherently anti-Western parts of the electorate, giving the same parties an additional boost. With the victorious ‘lateral coalition’ of left- and right-wing parties in Greece, the days of EU unity over Russia may now be counted. Putin’s investment in political alternatives may soon pay off.

In general, the emergence of anti-mainstream parties has already caused a political shift to the right, as a strategy of marginalization and defamation can only serve as a temporary fix. The preferred strategy of leaders has been to adopt part of those parties’ agenda, as can be seen in the UK or in Hungary. While this stance undermines the EU’s principles such as freedom of movement, the swing to the right has largely been grist to the mill of the alternatives.

Conclusion: EU leaders at a crossroads

The current crisis of liberal Europe is grave, rocking the EU to its very foundations from without and from within. Externally, it is about the ability of the EU to establish a workable order in the neighborhood. So far, EU leaders have failed to come to grips with Putin’s ambition to create a different Europe based on relations between the great powers. Internally, the EU’s liberal approach to order is questioned as well – both by the economic divergences between member states, and by the political movements arising on their back. This rise of anti-establishment parties and governments shows that functionalist integration has run its course and politics can no longer be ignored. The war in Ukraine connects all of those three challenges, as it resonates deeply inside the EU and acts as a booster to the prevalent internal problems. Acting on those challenges, Putin has intentionally deepened the EU’s crisis.

The crisis now compels the EU’s leaders to prioritize, to concentrate on the essence, and to make decisions. To some extent, this has already happened over the war in Ukraine: The severe, even though belated sanctions on Russia are a positive sign of unity. But that unity remains very fragile, and more resourceful efforts would be needed to solve the huge task of establishing regional order. Internally, the rise of anti-mainstream parties has become acute in Greece. While this poses many challenges, the new government has also one main advantage: The greater trust of voters, which would allow them to implement the reforms that the EU needs.

The downside risks for the EU are huge. If the alliance of far-right and left-wing ‘anti-imperialists’ were to gain additional ground, the Eurozone might unravel. The EU itself would become more and more blocked by disputes, with smaller regional integration projects arising on the continent. In any case, Russia would emerge as one of the new centers, realizing its dream of a Europe based on great powers. The new era could be marked by instability on a greater scale and on more dimensions.

Conversely, if the EU pulls together and embraces a forward-looking discourse that reaffirms its basic values and backs them up with resources, it may emerge stronger from the crisis. This would prevent Putin’s Russia from emerging as a key actor on the European scene and transforming the regional order. It would also transform the challenge itself: Russian politics has always mirrored developments in Europe, and the decline of the EU has empowered those advocating a traditionalist and isolationist Russia. An EU that re-emerges stronger and more united from this crisis is thus the best precaution against a belligerent Russia.