The Weakening Foundations of Western Power

1 Jun 2015

By John Rapley for ISN

From today’s vantage-point, it seems incredible that scarcely a dozen years ago some Western governments persuaded themselves that they had the wherewithal to invade a major Middle Eastern power, remove an inconvenient leader and install a friendly regime. The conviction that no threat was beyond the capacity of concentrated Western military power seems a distant memory in an age when America is trying to withdraw from its battlefields and ‘pivoting’ to concentrate its military resources. Today, Western military budgets – those of the US and its NATO allies, not to mention Japan – are either flat or declining. Lest one think this vindicates the camp which believes the world is getting less violent, one must caution that the trend is largely confined to the West. In 2013, while global military expenditure declined overall, simply removing the US from the calculation reveals a global military budget that external pagerosecall_madeby nearly two percent. As the West retreats, new powers, especially but not only China, continue rising.

Of course, it’s not the first time that the superpower has retreated from a foreign fight with its tail between its legs. Thoroughly chastened in Vietnam, the American fighting-machine came roaring back in the 1990s – new, improved and having digested the lessons of its earlier mistakes, which it put to good use in the first Gulf War. All the same, this time does appear to be different, because the economic landscape has changed markedly. Indeed, this time the foundations of Western power seem far more fragile.

The sources of relative decline

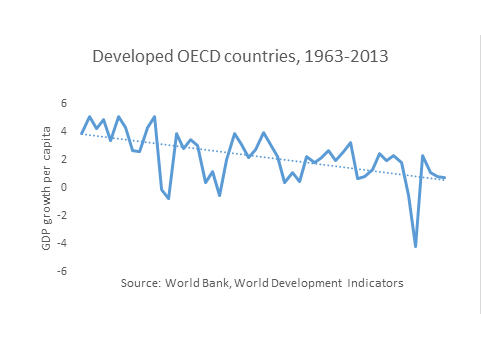

When the Vietnam War ended, rising oil prices and surging inflation had brought an end to the decades-long growth phase that had characterised the post-World War II West. Annual economic growth rates that had averaged in the 4-6% range in Western countries now slowed to zero. The apparent inability of the then-dominant Keynesian model of state-managed economic expansion to restore growth yielded a major political change. The election of Margaret Thatcher in the UK in 1979, and Ronald Reagan in the US the next year, ushered in a new economic model of free markets and a minimalist state – what came to be known as neoliberalism. Among the dominant features of this new model were trade liberalisation and a weakening in the power of unions, two changes which reinforced one another. Trade liberalisation made it possible for firms to outsource their production to low-wage zones, which in turn enabled them to threaten restive unions with job cuts.

The result was that real wages fell while profits rose. In the quarter century after 1980, for instance, corporate profits in the US nearly tripled as a share of GDP while real wages stagnated (according to the US Bureau of Economic Analysis). Initially, this new policy orientation seemed to be just what the doctor ordered for Western economies. By the late 1980s, growth had resumed. Assisted by declining interest rates (driven down by austerity policies and wage-repression), the West, led by the US, was scaling unprecedented heights of economic prosperity by the 1990s. The remaining opposition to neoliberalism then caved and re-oriented itself around a new generation of politicians led by figures like Bill Clinton and Tony Blair.

But while the 1990s were filled with heady talk of a ‘new paradigm,’ the boom obscured underlying trends, which remained less promising. In a nutshell, the shift of national income away from labour and towards capital had driven up returns on the latter, which produced a stock-market boom. Low-interest rates encouraged everyone to join the ride, and Americans bought stocks on credit with an abandon last seen in the 1920s. This fuelled a bubble, creating a so-called wealth effect. Feeling richer, Americans in particular went shopping. But rather than cash in their profits, they borrowed against their capital gains to spend, further stoking the boom.

A little-noticed feature of the decade’s global politics, one which was entirely cyclical, reinforced this trend. When a financial crisis broke out in East Asia in 1997, and spread the next year to Russia and Latin America, the global economy teetered on the brink of catastrophe. This prompted the US to act, lending the International Monetary Fund enough money to boost its war chest. The IMF then started bailing out crisis-stricken governments. However, a condition for IMF assistance was that recipient governments could not use capital controls to limit the rush to safety by panicked investors. So as Asian countries got bailout funds, a flood of money into Western, and particularly US, treasury paper followed. This drove down interest rates even further, giving a mature stock market yet a bit more room to run. But it was ultimately a blip. The long-term trend remained: Capital was moving to ‘emerging markets’ to take advantage of abundant cheap labour supplies, which were only being augmented by the continued opening-up of China.

When the panic of the Asian Crisis subsided and capital began flowing back to the developing world, the carpet was pulled out from under the stock market. In 2000, it duly crashed. As central banks tried to shore up asset values by cutting interest rates, a series of bubbles ensued, beginning with real estate. Each bubble led to a new crash in a rolling series of crisis-and-response that continues to this day. Meanwhile, deep in the foundations of the Western economy, there had apparently been an ominous development.

Research on productivity reveals that underlying productivity growth has been slowing for decades. A recent book by Tyler Cowen, The Great Stagnation, sums up the various arguments cogently, but he merely speak for a rising chorus of opinion which is growing more pessimistic. Technological optimists, led by our politicians, insist that the information revolution will so transform our lives that we will experience our next industrial revolution. But so far, there has been little evidence of this happening. Some, like America’s leading scholar on productivity Robert Gordon, now wonder if the major technological leaps of the past, like the steam engine and electrification, were essentially fortuitous one-offs which there is no reason to expect will be repeated. Technology is revolutionising our lives, to be sure. But it doesn’t seem to be doing that much to increase economic productivity.

Worsening the picture is the relative demographic decline of the West. Often overlooked by those who read future progress into past performance is that the two centuries of economic growth which transformed the modern world coincided with a demographic expansion which appears now to have run its course. Population growth has already turned negative in Japan and Germany, while economic crisis has reversed growth in Greece and Spain as well. Across the West, only immigration has kept the population from declining. The abundant cheap labour of the past two centuries which drove rapid economic expansion can in principle be replaced with still-cheap supplies from the developing world. But as the recent upsurge in nativist politics reveals, there are clear limits to the immigration option.

The end of growth?

The 2007-2008 financial crisis more or less brought growth to a halt in the West. Economists are divided over how to break out of this rut. Keynesians call for continued reflation while more orthodox economists insist on further austerity to keep interest rates low so that investment picks up. But most of them agree that the current slow-down can be overcome.

This comity may reveal less about the state of the economy than it does the state of economics. Take Britain, for example. Over the last decade, house prices external pagehave risencall_made by a fifth. However, in the same period, productivity has flat-lined (according to the UK Office of National Statistics). Driving house prices, in no small measure, has been the Bank of England’s loose monetary policy, which has flooded the economy with cheap money. Government policy, in other words, has further encouraged house-buying. But if property-owners are feeling sufficiently flush that they have loosened their purse strings, leading the country back out of recession in the process, the effect is likely to prove temporary. Unless rising wealth leads to renewed investment in productivity-enhancing technology, the experience will likely end as recent episodes of rising asset values did – which is to say, quite badly.

Relative decline is hardly a new topic in Western intellectual debate, and the pessimists have often appeared too quick to play chicken-little in the past. Nevertheless, optimists who maintain that Western growth rates will return to those of old may have an even worse record of prediction, at least so far. Despite regular reminders that we are on the cusp of a technological new age, the trend-line of growth in the Western world speaks volumes.

Unless evidence of a new age actually emerges, Western governments will continue to face the need to do more with less. Meanwhile, pressure from powerful constituencies, and in particular the rising demands of an aging population for pensions and health care, will inevitably prod politicians to look for savings outside their domestic budgets. Military budgets will prove irresistible targets, meaning that the West’s fighting-forces will need to become leaner and more efficient. This means that Western governments will have to pick their battles judiciously, use diplomacy more creatively, and practice a triage of sorts in deciding from which parts of the world they will need to scale back or even withdraw.

It won’t be an easy task, and if history is any guide, the transition may produce a less stable world.