European Security After the 2014 Watershed

7 Sep 2015

By Andreas Wenger for Center for Security Studies (CSS)

The crisis-ridden developments of the year 2014 marked the end of the post-Cold War epoch in which European Security was determined by the vision of an integrative and liberal security order. The model of a liberal and open Europe, which had dominated since 1990, was predicated on the assumption that security in Europe was indivisible and rested on a foundation of shared norms and institutional enlargement. This vision, which went unchallenged internally, offered guidance for the enlargement policy vis-à-vis the Eastern and Southeastern neighbors who were clamoring for admission to NATO and the EU. For a long time, it also appeared to be unrivalled externally, as even Russia seemed to adhere to this vision or at least abstained from actively undermining it. As a political objective, it was influential precisely because it deferred the question of what role a resurgent Russia should play and what part the states of “Intermediate Europe” would have in a European Security system.

However, since 2014, the dual challenge to the vision of an integrative and liberal European Security order can no longer be overlooked: Internally, it is jeopardized by a groundswell of illiberal political forces in many EU and NATO member states, the political fragmentation of the EU amid the euro currency crisis and fear of a “Grexit”, and the wearing thin of transatlantic relations between the US – increasingly focused on the Pacific – and an increasingly self-absorbed Europe; externally, by the simultaneous nature of the crises in the Ukraine in the East and over the Islamic State in the South, both of which are unmistakable manifestations of alternative concepts of order and strategic narratives along nearly the entire periphery of Europe.

The realignment of European Security must begin with a root cause analysis that reflects both the commonalities and the differences between strategic challenges in the East and South of Europe. It should be conceived as a strategic challenge in the field of tension between West, East, andSouth rather than as a series of isolated operational challenges along sub-regional (Eastern Europe, Balkans, Caucasus, Middle East, North Africa) and functional categories (internal security, defense, foreign policy). And it must result in a renegotiation of regulatory policy roles among the major Western actors, integrating both national and multinational aspects.

Ukraine: The Return of Geopolitics

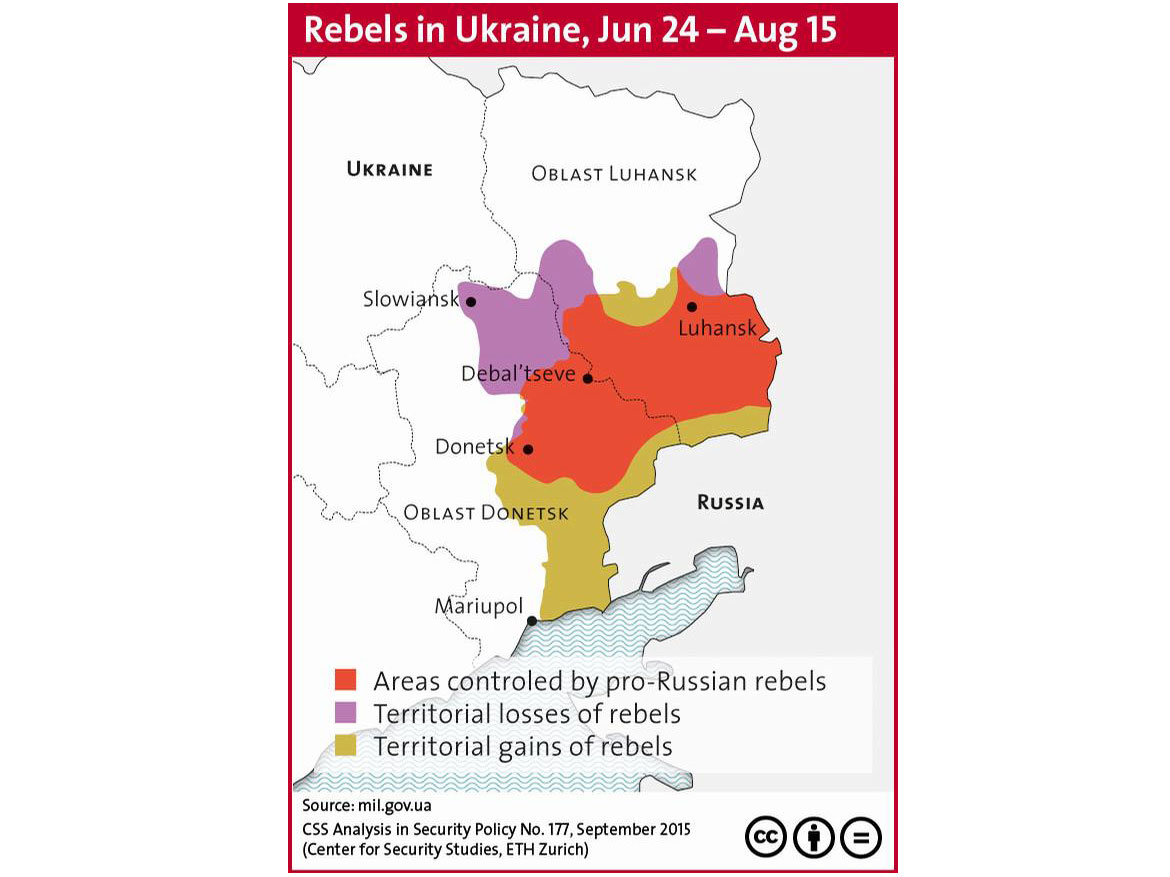

In the course of the Ukraine crisis, geopolitics has once more become a challenge to European Security. In two wars waged since 2008, Russia has made clear that it will no longer acquiesce to Western conceptions of order or the attendant expansion of Western institutions in its “near abroad”. In the war in Georgia, the aim was to prevent the strategic integration of Georgia into NATO. In the Ukraine war, the purpose is to prevent Ukraine’s political and economic integration into the EU.

Although the strategic estrangement between the West and Russia has been long in coming, the escalation of the crisis in 2014 came as a surprise to both sides. The overthrow of Viktor Yanukovych’s government and the signing of an association treaty with the EU was a strategic fiasco for Russian President Vladimir Putin. His newfound patriotic stance and the emphasis on Russia’s cultural uniqueness also reflected the fear that the “Orange Revolution” might threaten the country’s internal stability. On the other hand, the annexation of Crimea in flagrant violation of international law as well as Russia’s military intervention in Eastern Ukraine shocked many Europeans, who were stunned by Moscow’s ruthlessness in blocking the integration of Ukraine into the Western structures.

The events of 2014 have made obvious to all that the crisis between Russia and the West is of a geopolitical nature. Essentially, it is a conflict between two irreconcilable political and economic integration projects, namely the EU and the Eurasian Union, and over power and influence in the regions of Intermediate Europe. The Russian-controlled areas in Ukraine, Moldova, and Georgia effectively constitute territorial pawns that can be used to block the integration of those areas into the EU and NATO. Furthermore, Russia’s military action in Intermediate Europe had effects on the military balance between NATO and Russia. In the Baltic States and in Poland, the desire for security-policy reassurance grew, in turn setting off a debate within NATO over adapting the deterrence strategy.

The key question is in which direction Russia will develop, and how permanent its revisionist turn will prove to be. Russia is not a global power that enjoys a broad base of power. The relations that give shape to the structures of geopolitics are those between China and the US. Neither is there any functioning coalition of illiberal forces between Russia, China, and Iran that might attain dominance in Eurasia. Putin’s Russia is fragile domestically and vulnerable externally. It remains to be seen how the Russian elites will react to the high cost of pursuing a neo-imperial control over the country’s near abroad, or how they will position themselves with respect to the mutual economic interdependencies of the international order. One determining factor for the security of Europe is the fact that Russia’s future remains highly uncertain for the time being.

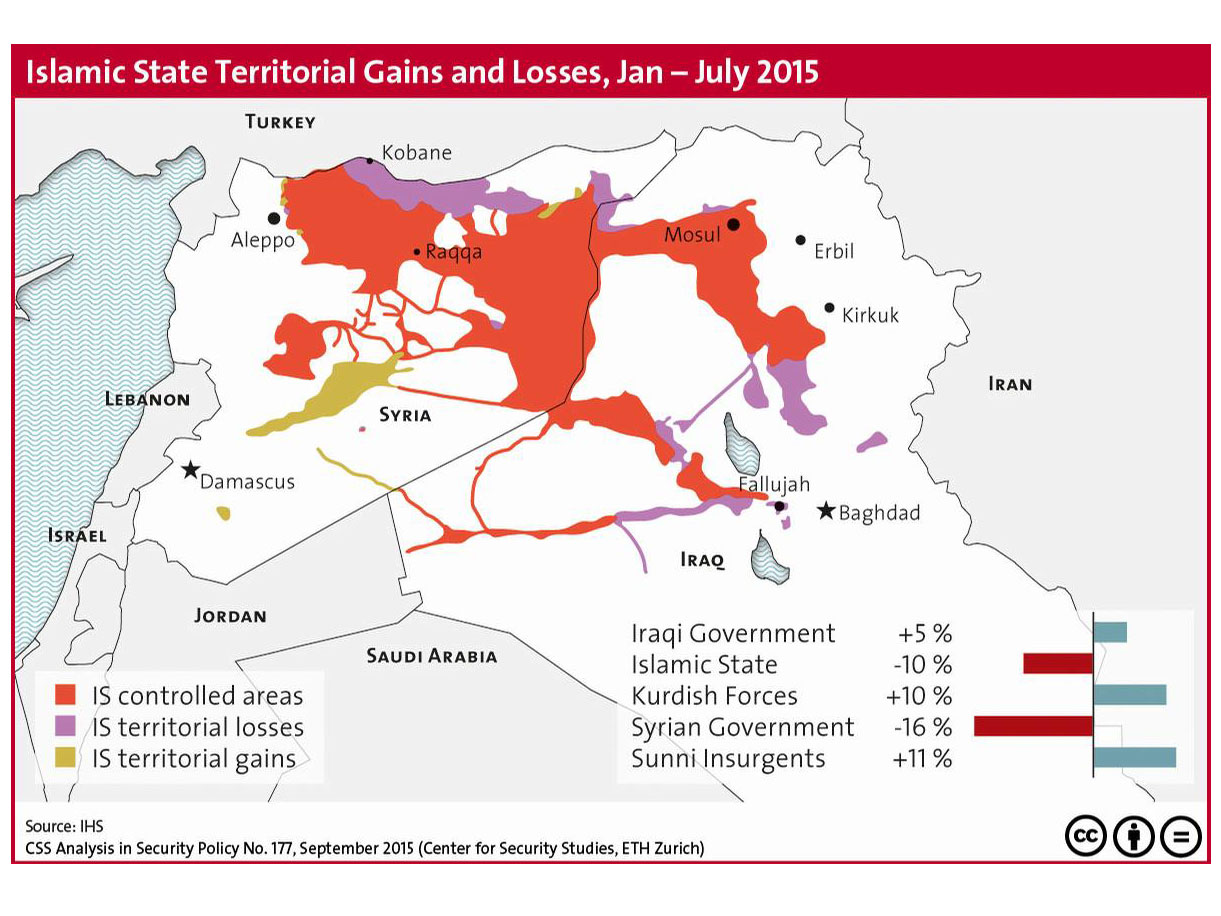

The IS: Alternative Statehood

When Europe turns its gaze southward, it finds that here, too, alternative notions of order have manifested themselves since 2014. However, from a European point of view, this challenge is not primarily a geopolitical one. The narrative of radical political Islam is fed by a combination of anti-Western and anticolonial pan-Arabism and Islamism conceived as a religious and social revival movement. In its radical version, it constitutes a challenge to the Western concept of statehood.

The hope that the societal reform movements might gain the upper hand in the long term, which had still been prevalent in 2011, soon gave way to an increasingly sober view. Both in Egypt and in the Gulf monarchies, reactionary and authoritarian forces doggedly remained in place. The rise of the Islamic State (IS) in 2014 made it increasingly clear, moreover, that the Arab Spring had not eliminated the breeding grounds of radical Islamism. On the contrary: In Syria and Iraq, the central state disintegrated, with secular and religious concepts of statehood competing for influence, while fighters and refugees alike increasingly ignored meaningless border demarcations in their movements. At the same time, these opaque and confusing civil wars were superimposed with the proxy wars of external powers, for instance the tensions between Iran and the Shi’ites vs. Saudi Arabia and the Sunnis or those between the US and Russia.

The increasing destabilization in the South remains just as much of a challenge to European Security as the developments in the East. The US is attempting to facilitate an evolutionary development in the region while preserving national borders, without becoming caught up in yet another war. Besides stabilization efforts in Syria and Iraq, its attention is focused on recalibrating its relations with the rising powers on the periphery of Arabia (Iran, Turkey, Israel). The Europeans, for their part, are primarily concerned with the repercussions that the regional dynamics might have for systems of internal security in Europe. Their main concerns are the phenomena of returning “foreign fighters”, irregular migration across the Mediterranean, and the risk of disruptions to the energy flow from the region. European Security must be prepared for sustained instability on the Southern periphery.

Realignment: West – East – South

So far, the West has reacted to the Eastern and Southern security policy challenges without relating the different regional and functional challenges on Europe’s periphery to one another. The disunity in operational matters will be easier to overcome, however, if the respective challenges are considered in a broader strategic context. The various attempts to grapple with the realignment of European Security must take place in a comprehensive field of West – East – South tension.

The contemporaneous nature of the crises in the East and South of Europe necessitates a comprehensive debate over the question of what the alternative concepts of order and strategic narratives on the European periphery mean for the self-conceptions of the West and of Europe in particular, as well as for the future of European Security. The challenge from Russia cannot be reduced to a classic geopolitical conflict; too strong are its manifestations in the economic sphere and in the form of a hybrid threat that includes targeted disinformation, cyberattacks, and political infiltration. Nor can the challenge in the South be explained as the work of non-state actors exclusively, being as it is closely enmeshed with regional dynamics of regulatory policy and the specific interests of individual Western actors.

A debate over the future of European Security that is fixated on Russia will tend to focus narrowly on the incompatible extreme positions of “Putin sympathizers” and “Putin isolators”. The former regard the Western expansion strategy as the main reason for the current crisis in relations with Russia and emphasize the role of the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE) as a pan-European Security institution; the latter believe that Putin’s revisionist turn is the cause of the crisis and argue that the security of the Eastern European alliance members as well as the right of the Intermediate European countries to choose alliances freely can only be ensured by expanding a forward defense and accelerating their convergence with the Western institutions. Neither of these two explanatory approaches can contribute new strategic guidelines for the realignment of European Security that are commensurate to the complexity of the challenges.

A strategic debate that considers the Russian question in a broader regional and global context, on the other hand, opens up new avenues for action: It minimizes the potential for tension between the Europeans and the US by taking into consideration the potential for selective cooperation between the West and Russia (Iran, Islamic State, the Arctic, etc.) and acknowledging Russia’s role in the international organizations. At the same time, it also minimizes the potential for intra-European tension between Northern and Southern Europeans by positioning the security-policy challenges in the East and South in a common strategic context.

Consolidation Before Expansion

In view of the internal and external erosion of the European Security order, the strategic focus of the West must shift from expansion to consolidation. Europe must accept the fact that its norms, and the concepts of order associated with them, are not shared by all its neighbors. The fact that the prospect of accession evokes, and will continue to evoke, high expectations in many countries do not make the situation any easier. The West must not question its own norms and values, nor must it take the prospect of accession off the table. The institutional expansion processes of NATO and the EU deserve judicious appreciation as appropriate and successful responses to the strategic upheaval of the early 1990s.

Today, however, it should also be acknowledged that an overly narrow focus on a selfcentered expansion strategy can no longer ensure sustainable solutions for pan-European security questions. What is needed is a set of more flexible solutions that leave space for divergent values and concepts of statehood. Primarily, it is the instrument of conditionality that will have to be reconsidered; it should no longer be kept at the center of economic and political relations with neighboring states at the cost of ignoring the dynamic of alternative incentive systems. The conditionality of accession is increasingly reaching its limitations, first of all because the reforms demanded are more difficult to carry out in the context of an acute security crisis, and secondly, because the cost-benefit calculations of local elites are subject to positive and negative incentives (rewards and threats) from third states (e.g., Russia).

Not only in terms of economic policy, but also from the security-policy point of view, a key question remains whether the European states will succeed in framing their relations with neighboring countries increasingly in terms of shared interests and pragmatic cooperation. This would contrast with the current policy approach, which operates by codifying uniform intra-state norms and through a process of juridification of political relations. The EU will not find it easy to leave behind its technocratic approach, based on a stance of “take the acquis or leave it”. Nevertheless, it will have to do so, initially on the national, bilateral, and minilateral levels. The quest for new regional convergence mechanisms in the field of tension between less strict conditionality and a deferred process of accession remains one of the key challenges in the deadlocked EU Neighborhood Policy.

The US Remains Important

The “Watershed of 2014” also necessitates a renegotiation of the roles that the main Western actors will play in regulatory policy both at the multilateral (NATO, EU, OSCE) and at the national, bilateral, and multilateral levels. The realignment of European Security requires a high degree of coordination and is predicated on a broad strategic approach. The point is to ensure that the initiatives pursued by NATO, the EU, and the OSCE are not mutually obstructive. What is needed is loose coordination by a group of realigning key actors.

In the future, European Security will be conceived more as a transatlantic affair again. Even though US engagement may become more selective, it remains a central regulatory force in Europe. NATO is increasing in terms of regional political importance, and remains the mainstay of Euro-Atlantic stability in the face of Russian imponderabilities. Conceptually, it can continue to orient itself along a twofold Harmel Policy that combines political dialog with deterrence and defense. A key remaining question is how far to expand the military infrastructure and stationing of heavy equipment in the Baltic states as well as in Poland, Bulgaria, and Romania as part of a display of alliance solidarity and reassurance. Furthermore, striving for geopolitical balance at the transatlantic level and undertaking integrative efforts for regulatory policy at the pan-European level are not mutually exclusive options. A strengthened OSCE can serve as a pan-European bridge in terms of both economic connectivity and security-policy cooperation. Nevertheless, due to the consensus principle, its scope of action will still never extend beyond what constitutes the lowest common denominator of political will in all member states in the years to come.

The EU, on the other hand, is declining in importance as a force of international order due to its military deficits and its plodding mechanisms of decisionmaking. In terms of security policy, however, it remains important: On the one hand, the concept of security through integration will remain the normative foundation of European Security. On the other hand, the EU still plays a central role with respect to comprehensive domestic security provision (police, justice system, infrastructure). Considering Russia’s hybrid warfare in the East and the challenges of non-state actors in the South, the internal robustness and resilience of European societies is a question of crucial importance.

The security-policy challenges in the East and South resemble each other to the extent that the discernible risks and challenges cannot be suitably grasped using traditional functional categories such as “internal vs. external security”, “civilian vs. military instruments”, or “state vs. nonstate actors”. The importance of collaboration in the realm of internal security is increasing not only in the EU; but also in NATO. The concept of resilience, which emphasizes a decentralized form of governance, offers new options for police, civilian, intelligence, and military cooperation between NATO and EU states.

Coordinated Political Leadership

In the future, European Security will again be conceived and practiced in increasingly national and minilateral formats. Security policy challenges – as well as the instruments designed to deal with them – have become so complex and convoluted that more flexible forms of cooperation involving a multitude of state and non-state actors are becoming more important. Uncoordinated national decisions are not to be expected because the ability to deal with security policy challenges purely on the national and state level is further declining in the context of budget cuts and globalized markets.

The disparate national reactions to the crises in the West, East, and South are nevertheless crucial for the reorientation of European security. One key question is whether the new and old main actors will succeed in ensuring coordinated political leadership. In many respects, Germany has a key role to play, and is challenged, both in the field of foreign policy and strategically, on more fronts than ever before. However, for structural reasons, it continues to depend on functioning partnerships with France (West and South) and the US (East and South). The UK, caught up in the debate over EU reform, is maintaining a low profile and has lost influence at least temporarily. Poland, on the other hand, has gained importance; in the axis Poland-Germany-France, it strongly advocates in favor of isolating Russia. For the time being, the ball is in the Europeans’ court. However, close coordination with Washington remains indispensable if the crises in the East and South should continue to escalate.