Afghanistan: Back to the Brink

8 Sep 2015

By Prem Mahadevan for Center for Security Studies (CSS)

In the foreseeable future, no terrorist attack on the scale of the 2001 strikes in the US is likely to be launched from Afghan territory. But this is no cause for complacency. However much Washington seeks to play down its failure to defeat the Taliban insurgency, Afghanistan is sliding into chaos comparable to the Soviet retreat in 1989, which was followed by a civil war. Even if public and media attention in the West is no longer focused on Afghanistan, the country’s future trajectory will still impact Western homeland security.

In all this, leadership struggles within the Taliban are crucial. July 2015 revealed that the Taliban’s supreme leader, Mullah Omar, had died in Pakistan more than two years previously. Yet, bizarrely, this same dead Mullah Omar had addressed his followers via a recorded message only a few days before his death was announced. In what must have been a fabrication, “Omar” exhibited a surprising willingness to negotiate with the Afghan government – something that the real Mullah Omar had opposed during his life.

Far more significant than the fact of the Taliban chief ’s death was the duration for which it had been covered up by the insurgent leadership. Suspicions arose that Omar may have been assassinated by his deputy, Mullah Akhtar Mansoor. Mansoor, a narco-trafficker and a protégé of the Pakistani intelligence service with strong ties to the al-Qaida-affiliated Haqqani network, had been acting as the Taliban’s lead negotiator with Kabul before news of Omar’s demise was leaked. That he held these negotiations in the name of his long-deceased chief threw his credibility into question. The haste with which he assumed the title of supreme leader stirred further opposition among veteran Taliban field commanders.

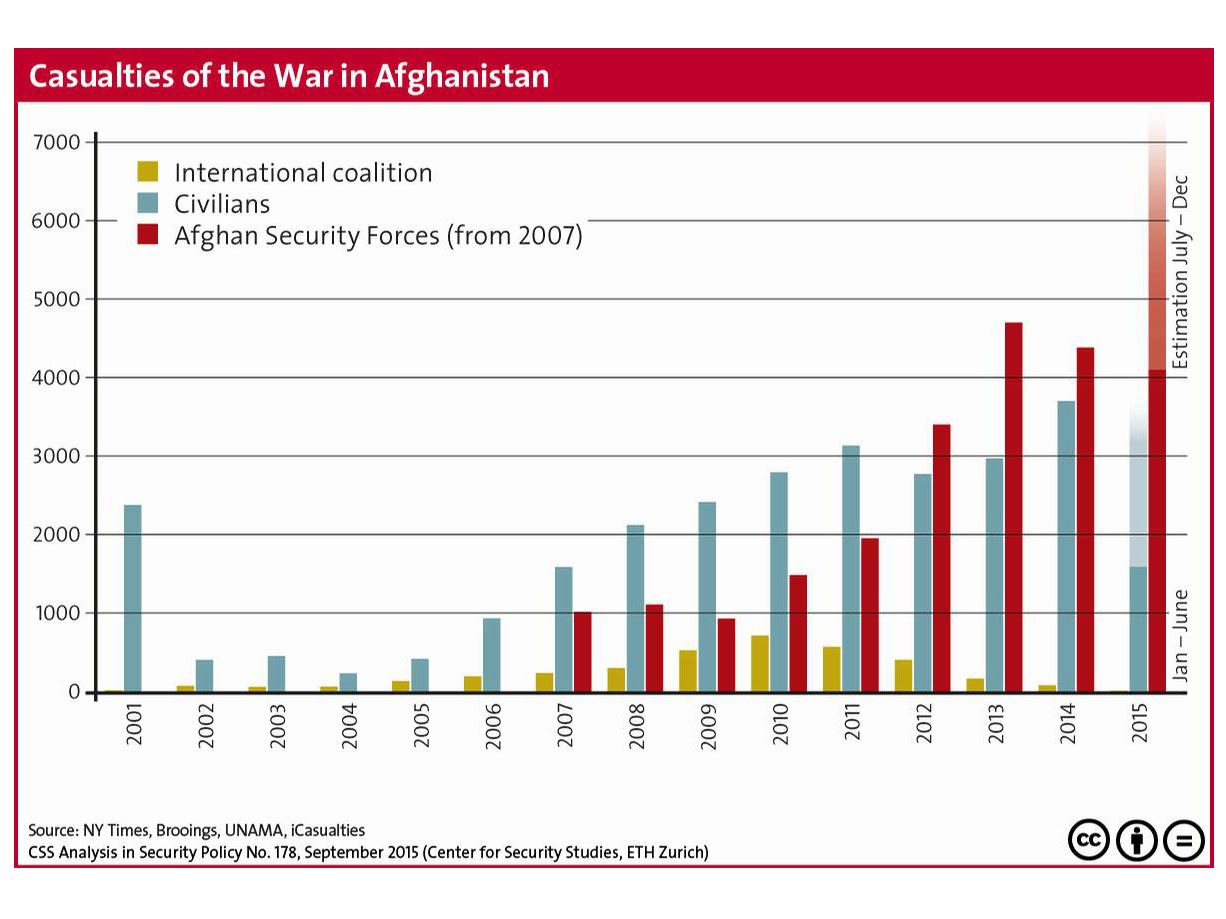

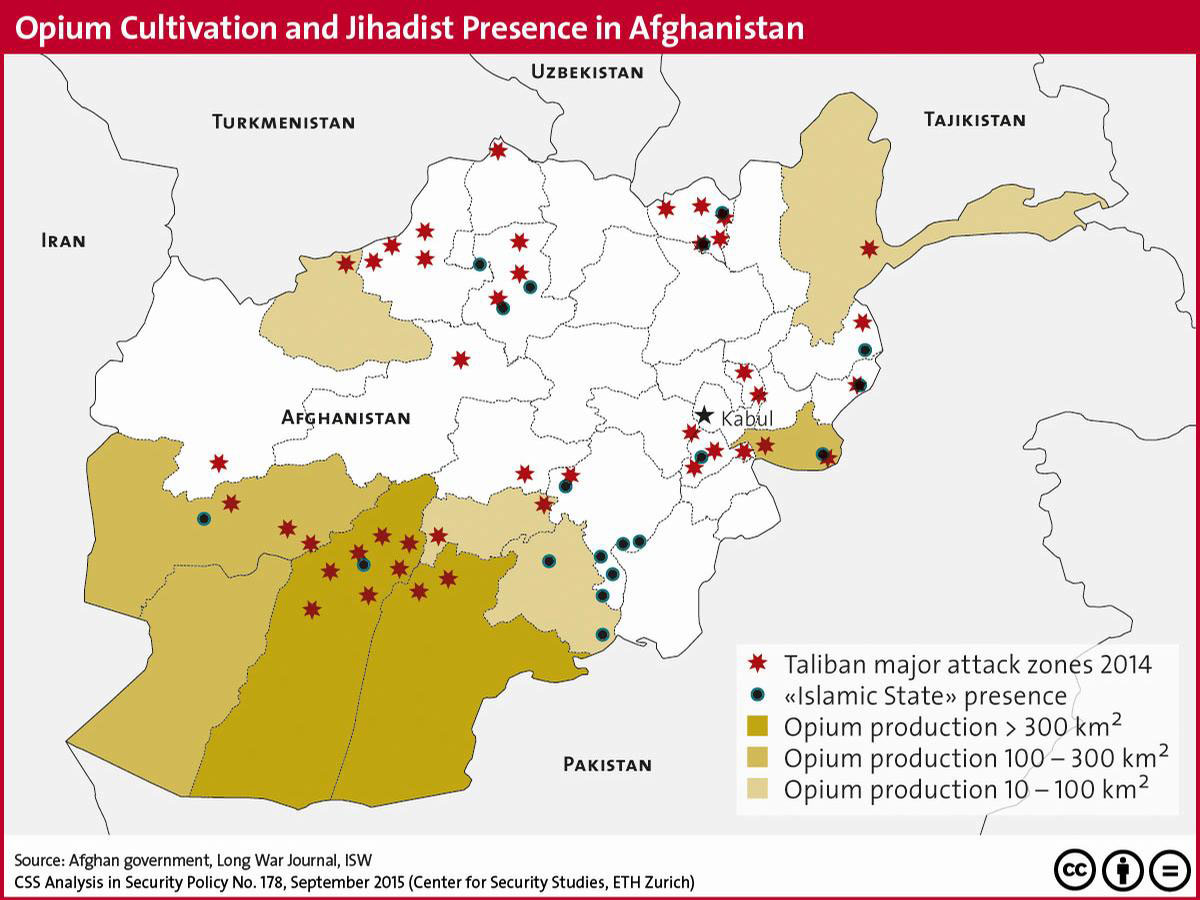

These developments suggest that the war in Afghanistan is about to enter a new phase of intensity. The statistics speak for themselves. Afghan security forces are suffering casualties including dead and wounded of up to 300 personnel per week, which is not sustainable in the long run due to their limited manpower base. On average, nine civilians were killed every day between January and July 2015. The bulk of civilian deaths are now occurring in ground com bat operations as opposed to bombings, indicating that the Taliban have moved to a more territorially-defined stage of insurgency. Their 2015 spring offensive was launched from the northern areas of Afghanistan, indicating a geographic expansion of their operational space. In previous years, their spring offensives had come from the south.

The elevation of Sirajuddin Haqqani, leader of the Haqqani network, as Mansoor’s deputy and the Taliban’s top military strategist suggests that al-Qaida is finally about to get its long-awaited moment of re-entry into Afghanistan. Western intelligence agencies believe that the Haqqani network is more operationally connected with global jihadist groups than the majority of the tribally-organized Taliban who possess a localized worldview. Sirajuddin is reportedly a member of al-Qaida’s Executive Council, and the US has offered a USD 10 million reward for him, the same as had previously been placed on the head of Mullah Omar. This should end hopes that the Mansoor Taliban might act as a moderate force in Afghan politics, if they enter into a power-sharing arrangement with Kabul. Rather, one should expect a process of factionalization within the Taliban insurgency that could benefit not only al-Qaida, but potentially also rival jihadist groups such as the “Islamic State” (IS).

One of the reasons for the defection of Taliban fighters to the IS was a suspicion that Mansoor was only negotiating with Kabul to secure political appointments in Afghanistan for members of his own Ishaqzai tribe. He was perceived as betraying the interests of other Taliban leaders. Desperate to consolidate his position as the Taliban’s new leader, Mansoor has now felt compelled to announce the intensification of jihad in Afghanistan.

A Forgotten but Escalating War

Although the International Security Assistance Force (ISAF) terminated its mission in December 2014, the US still retains 9,800 troops in Afghanistan, mostly for guard duties, training missions, and special operations. These troops are still scheduled to be withdrawn by the end of 2016. With the Afghan President Ashraf Ghani keen to compromise with the Taliban, hopes had been raised of a negotiated peace. These are however, fading due to four factors. The first is political: Ghani’s own legitimacy is shaky, considering that he was only able to assume the presidency after his election opponent, Abdullah Abdullah, conceded defeat despite an ambiguous voting result. Abdullah accepted the lesser post of chief executive. The two men have differing views on the Taliban. Abdullah sees the insurgents as representing a medieval ideology that has no space in the country’s developmental vision, while Ghani believes that unless they are brought into the political mainstream and their growing military capability is acknowledged, the country is condemned to more violence.

The second factor that has diminished hopes for peace is economic: Afghanistan is thought to require USD 7 billion annually over the next decade just to pay civil servants’ salaries, keep infrastructure maintained, and provide domestic security. Afghan revenue at present accounts for 29 per cent of the national budget, the remainder coming from foreign aid. With the economy stalling for the first time since 2003 and the Afghan currency depreciating sharply, the government will remain dependent on foreign funding. The insurgents know of this weakness and thus see little reason to compromise. For them, history is merely replaying itself according to the script that followed the Soviet withdrawal in 1989 – a weak regime, sustained by overseas donors, is holding off armed rebels only as long as its finances last. Sensing that the West has no interest to continue with nation-building or subsidizing a lost cause, the Taliban feel that victory is within reach and view peace talks as merely a prelude to marching on Kabul once again.

The third factor is military: up to one-third of Afghan territory is at high risk of insurgent violence. Although this is insufficient to translate into a swift seizure of power, the extent to which Afghan security forces have grown reliant on Western air and intelligence support over the past decade is now hampering their operational response. The Afghan air force has few ground-attack aircraft for counterinsurgency duties, and is struggling to recruit pilots who can be trusted not to change sides. During the Taliban’s rise to power in 1994 – 6, much of their success came from the defection of Afghan army and air force personnel, together with their equipment, at crucial battlefield moments. To avoid similar occurrences, Kabul has intensified personnel screening. However, the discovery in 2015 that several weapons captured during the latest spring offensive came from government arsenals suggests that the insurgents still have facilitators within the Afghan security forces.

The fourth factor is geostrategic: Afghanistan’s simmering tensions with Pakistan. The US, China, and Russia want Pakistan to broker a peace settlement between the Afghan government and the senior Taliban leadership. Islamabad for its part is fronting its preferred faction of the Taliban, the Mansoor faction, as the only negotiating partner with Kabul. The Pakistani intelligence service has quietly ousted all other Taliban factions who wish to retain a degree of political independence and who chafe at the stranglehold that Islamabad exercises over Afghan affairs. This situation is analogous to the Soviet-Afghan War, when Pakistan insisted on being the West’s sole intermediary with the Afghan mujahideen and then used this position to strengthen its own proxies, all radical Islamists, while marginalizing more moderate resistance factions.

Terrorist Group Power Struggle

To some extent, the war in Afghanistan already represents a worsening threat to the West, regardless of how events play out. If the Mansoor Taliban, with its Haqqani-provided manpower and firepower, prevails over dissident Taliban factions, al-Qaida would be a beneficiary. Western experts worry that the latter, stung by personnel losses in Afghanistan-Pakistan as well as in Yemen, is actively seeking to carry out a spectacular attack in the West. Having already lost a great deal of its recruitment base in Syria and Iraq to the IS, al-Qaida urgently needs to regain credibility as a functional actor if it is to remain relevant in jihadist politics. Since operational success has been the key to the IS’ appeal among new-generation terrorists, al-Qaida will have to compete on similar terms. The expansion of its existing safe havens in Haqqani-controlled areas for attack planning and logistical preparation is exactly what the group needs at this juncture. Several past al-Qaida plots against Western homelands have been traced to Haqqani territory, which in turn has been prioritized for US drone strikes.

On the other hand, if the Mansoor Taliban fails to assert control over the insurgency in Afghanistan, the country could see further a splintering of jihadist groups. Already, former Taliban members who have been expelled for disciplinary infractions or are disillusioned with the luxurious lifestyle enjoyed by their leaders in Pakistan have rallied under the IS banner. There is a perception that revenues gathered from the Afghan drug trade are not being put to common use, and are instead being appropriated by the top leadership for personal benefit. Reliable sources allege that 70 – 80 per cent of all narco-trafficking proceeds obtained by the Taliban go directly to the leadership, while the Taliban fighters on the ground have to divide the remainder among themselves. Since they run the majority of risks, such an unequal distribution of rewards has sparked resentment among local commanders.

Unlike the 1990s, when senior Taliban clerics practiced austerity, many political figureheads in the insurgency today show off their wealth in the form of flashy vehicles and palatial residences in the Pakistani cities of Peshawar and Karachi. This has prompted a generational upsurge from younger commanders in the field and created conditions for the latter to defect towards the IS. Part of the appeal is also egotistical: the leader of the Taliban is merely a regional “emir”, who according to Islamic convention, is theoretically one among many emirs worldwide all owing allegiance to a higher “caliph”. Taliban fighters who rebrand themselves as warriors of a global caliphate are promoting themselves to a higher status than mere foot soldiers of an Afghan emirate. Thus, the IS label has gained some currency in Afghanistan despite socio-cultural and linguistic barriers.

To set up a new identity for themselves, dissident Taliban factions have emulated the IS trademark brutality, beheading their former comrades and burning poppy fields in an effort to “cleanse” society. They have been joined by Uzbek militants fleeing counterinsurgency operations in northwest Pakistan. Gulbuddin Hekmatyar, an Afghan Islamist who is a long-standing rival of the Taliban, has also reportedly announced his affiliation with the IS. Interestingly though, there have been few accounts of foreign fighters from outside the South Asian region travelling to Afghanistan to join the IS.

Funding IS in Afghanistan

Anecdotal reports suggest that IS cadres in Afghanistan are flush with cash. Although the expert consensus is that there are few direct contacts between the IS franchise in Afghanistan and the central leadership in Syria-Iraq, it is possible that seed money has been provided to the new cadres. There is already a precedent for skill-sharing between the Iraq and Afghanistan theaters: In 2005, Iraqi jihadists taught the Taliban how to assemble powerful improvised explosive devices and use suicide bombers to maximum effect. The result was a sharp rise in terrorism-related casualties from the following year, which has never abated. It is thus possible that clandestine contacts have been created to transfer funding and technical knowledge to the Afghan branch of IS, even if the latter remains largely autonomous of Iraqi control.

Another possibility is that IS, with its demonstrated talent for racketeering in Iraq, is taking over parts of the Afghan drug economy while attacking those controlled by the Taliban. Reliable reports suggest that opium cultivation is booming in Afghanistan. One of the provinces being contested between the IS and Taliban, Helmand, accounts for almost 50 per cent of opium production in the country. In the eastern province of Nangarhar, where the IS drove the Taliban from six of the province’s 22 districts, they have tried to shut down the drug economy, possibly out of concern that they might not be able to exploit it themselves due to Nangarhar’s close proximity to Taliban strongholds in Pakistan. And there are strong grounds for believing that at least part of the opposition to Mullah Mansoor from within the Taliban itself, mainly comes from his having cornered large portions of the drug trade at the cost of other insurgent leaders who are now in open revolt.

Which Way Forward?

Between 7 and 10 August 2015, at least 80 people died in a series of terrorist attacks centered on Kabul. The Taliban claimed responsibility for operations targeting government installations, but not those primarily directed at civilians. Even so, patience seems to be waning in the Afghan government. President Ghani has bluntly accused Pakistan of spurning his goodwill overtures and continuing to wage what he called an ‘undeclared war’ on Afghanistan, using the Taliban as a proxy. Islamabad for its part insists that it is committed to an Afghan-owned and Afghan-led peace process. Given how dependent the Taliban leadership is on Pakistan’s support, however, there are doubts as to whether the latest surge in attacks is the merely work of rogue elements within the insurgency, possibly the IS, or is in fact a negotiating tactic to further weaken the Afghan regime before another round of talks. In either case, much will depend on whether Mullah Mansoor can assert his authority.

For the immediate future, the continued presence of US soldiers in Afghanistan and the ability to employ drones for targeted killings of jihadist leaders, even if on a diminished scale, limits the chances of a major attack being launched by al-Qaida on the West. What is almost certain is that the number of international terrorist plots being planned on Afghan territory will rise, in anticipation of a total withdrawal of US troops at the end of 2016. In the interim, the Afghan government is trying to slow the spread of insurgency by recruiting tribal militias as local vigilantes. This could once again lead to the emergence of a warlord political economy, as existed during 1992 – 4 immediately before the Taliban first appeared as a force in Afghan politics.

However, in the event that sanctions on Afghanistan’s neighbor Iran are substantially eased, following the recent nuclear deal, Kabul might be poised to reap a windfall. The development of the Iranian port of Chabahar through international investments could significantly lessen Afghanistan’s economic dependence on Pakistan in the long term, and thus indirectly weaken Islamabad’s current negotiating position. Many Taliban attacks over the past decade have been aimed at forestalling such an eventuality by attacking road construction parties working to improve links between Afghanistan and Iran. If the Afghan economy and military show sufficient resilience over the next 18 months to withstand the intensification of insurgent violence, then the final departure of Western troops might not automatically herald a return to civil war. This question is especially important for the security of Western homelands, as the two alternate scenarios – a Taliban/Haqqani entry into the Afghan government or a splintering of the Taliban in favor of IS – would ensure that Afghanistan once again becomes a terrorist safe haven.