We Need to Talk About NATO

29 Sep 2015

By Richard Reeve for Oxford Research Group (ORG)

This article was external pageoriginally publishedcall_made by the external pageOxford Research Group (ORG)call_made on 17 September 2015.

Corbynism in context

At the outset, two things need to be restated. The first is that Corbyn has just taken his place as the Leader of the Opposition. That is, he leads the party in Westminster that has just lost a general election. With fixed-term parliaments and a Conservative majority in the Commons, the next general election is unlikely to arrive before May 2020. Thus, beyond asking awkward questions, neither Corbyn nor his party are likely to have much impact on defence policy, such as this autumn’s Strategic Defence and Security Review (SDSR), for at least five years.

The second is that it is the Labour Party rather than its leader that sets party policies. Corbyn ought thus to preside over a party that, at least in the short term, remains committed to Trident renewal and an increase in UK arms exports, as per its doomed 2015 election manifesto. For now, the forum for the fiercest debate on British foreign and defence policy is likely to be within the Labour Party. The parliamentary party’s position towards the renewal of Trident, which aligns Corbyn more with the Scottish National Party (SNP) and Liberal Democrats than with many of his own MPs, may be particularly divisive ahead of the ‘Main Gate’ vote which would seek parliamentary approval to replace Trident, expected in early 2016.

More to the point, there does not seem to be any appetite within the Parliamentary Labour Party or the wider party for the UK to leave NATO. An external pageAugust 2014 opinion pollcall_made by Chatham House found that 60% of Labour voters (and 61% of all respondents) thought that NATO was ‘vital’ or ‘important’ to the UK’s security. Labour Party policy in the early 1980s (when Corbyn was first elected to the Commons) was to leave NATO but for the last three decades it has been squarely behind the alliance that the iconic Labour government of Clement Attlee co-founded in 1949.

All this means that Corbyn is highly unlikely to make UK withdrawal from NATO any sort of priority. However, he is known to ask difficult questions and some of these may include: What is NATO’s current purpose as a security alliance? Does NATO’s recent focus on ‘out of area’ operations contribute to European security? Would its further expansion enhance or undermine European and British security? What role must nuclear weapons play in the alliance’s deterrence strategy? What drives NATO’s commitment to its members spending a minimum 2% of GDP on their militaries?

NATO’s narrative of success

NATO has championed itself as “the most successful defensive alliance in history” (London Declaration, 1990), having precipitated the collapse of the Soviet Union and its Warsaw Pact alliance through its sustained superior technological development, mass communications and economic growth. At least in its early years, Stalin’s USSR was in expansionary mood and the alliance may well have safeguarded the fragile democracies of Western Europe’s frontline states, albeit neutrality or non-alignment seemed to achieve similar ends for such peers as Finland, Austria and Yugoslavia.

After 1990, when Corbyn has said that NATO should have been phased out, the ongoing legitimacy of the organisation has been bolstered by the clear desire of the majority of former Soviet satellites to join it. Since 1999, twelve formerly Communist states, including three former constituents of the USSR, have acceded to the alliance, with another three or four progressing towards membership. Post-2014 crises in relations with Russia have even prompted such stalwarts of democratic neutrality as Sweden and Finland to consider joining NATO.

For its part, NATO has repeatedly reaffirmed its ‘open door’ to all European democracies and its aim to unify Europe under a single security regime. The most significant success of the NATO alliance may well be to have created and enforced this security regime under which the economic and political structures of the European Union were nurtured and flourished. Tellingly, while the EU and European NATO are not coterminous, all but one (Serbia) of the EU’s 16 new and negotiating members in Central and Southeast Europe are current or aspiring members of NATO.

The view from Central and Southeast Europe is now at least as important to NATO as the perspective of Brussels, London or Washington. While Western Europe feels more irritated than threatened by the external pageRussian paper bearcall_made, and the US is far more concerned by the emergence of China as a genuine superpower, few in Central Europe have ever doubted that Russia would rise again as a major player in Eurasian geopolitics.

Even more important is the view from Moscow, which shares its former satellites’ zero sum evaluation of European security and sees NATO as an inherently anti-Russian alliance whose ceaseless expansion is part of an ongoing strategy to contain, encircle and neutralise it. Thus has Putin sought to rebuild both Russia’s economic and security alliances in its ‘near abroad’ through the Eurasian Economic Union and Collective Security Treaty Organisation. Georgia, Ukraine, Moldova and perhaps Serbia are the last torn states in Europe where Moscow and NATO vie for influence.

Where Corbyn is likely to challenge NATO is on its open door to admitting these former Soviet states, which he sees as unnecessarily antagonistic to Moscow. In this he may find that his views coincide with those of many of NATO’s military leaders. They worry about the alliance’s expansion as a political project despite its inability to defend new and ill-equipped territories to the east as well as entrenched anti-western attitudes among some post-Soviet security elites. In any case, Russian occupation, annexation or recognition of separatist regions claimed by Georgia, Moldova and Ukraine will stymie their ambitions to join NATO for the foreseeable future.

NATO in search of identity

Another sphere in which Corbyn is likely to question NATO orthodoxies is in relation to its post-1990s identity not just as a defensive alliance but as a proactive ‘Crisis Management’ organisation that mounts expeditionary, and sometimes offensive, operations well beyond its own borders.

Ironically, NATO made its first use of force only after the threat to Europe from its original adversary, the Soviet Union, appeared to have vanished. Since 1993, it has deployed and commanded armed forces in Bosnia, Kosovo, Afghanistan, Iraq, the Gulf of Aden and Libya on missions ranging from military training to counter-piracy to peacekeeping and civilian protection to regime change and territorial occupation.

While the Bosnia mission and the ongoing anti-piracy Operation Ocean Shield off Somalia have met with some success, interventions in Kosovo, Afghanistan and Libya have flouted or tarnished international law without obviously enhancing Euro-Atlantic security. At best, as in Kosovo, NATO has been left with an open-ended peacekeeping dilemma. At worst, as in Afghanistan, it has been sucked into a major war (even the meta ‘War on Terror’) without clear strategic objectives. In all three cases, but most acutely in Libya, the easy tactical victory of NATO’s superior military technologies has been belied by the strategic disaster of its attempts at (or aversion to) post-conflict state-building.

While NATO is expected to persist with the Strategic Concept it signed up to in Lisbon in 2010 until its 2020 summit, the alliance already appears to have moved away from that document’s focus on capacity to mount ‘crisis management’ operations ‘at strategic distance’. This reflects a number of issues. One is the strategic focus of the Obama administration on the Pacific and China, where other NATO powers have much more limited interests and capabilities. Another is the chastening experience of strategic failure in Afghanistan and Libya. More pressing since 2014 is the crisis in relations with Russia, which has focused minds on the original task of territorial defence, and the return to combat operations against Islamic State of the US, UK and at least six other NATO allies. This mission is commanded by the US outside of NATO structures, perhaps reflecting a concern that NATO is seen as a Western, Christian, even ‘Crusader’ alliance in the Middle East.

Few of these conditions seems likely to change much over the course of the current parliament. The post-Obama US presidency (from January 2017) is likely to have the largest influence over NATO’s next strategic concept but further US drift from European security appears likely. Of the three regions (Europe, Middle East, East Asia) of which the US has positioned itself as external security guarantor since 1945, Europe is still by far the most stable and best resourced and coordinated. Europe will therefore be expected to do more at home; if defence budgets are not to rise, that probably means less focus on expeditionary capabilities.

Violent conflict in the Middle East is likely to be a major feature of Mediterranean security for the generation to come and several NATO members will be involved in military activities along its frontiers, from Libya to Iraq. Invoking Article 5 (on collective defence) cannot be ruled out if Turkey, Greece, Italy or another member state were attacked, but the appetite to use NATO for more proactive military interventions in the Greater Middle East seems to have waned in favour of US and EU efforts to bolster Arab or African capabilities.

It is difficult to predict the future course of US foreign policy let alone the nature of NATO-Russian relations or the Islamic State in 2020. However, European NATO members’ perceptions of their security environment and threats have been transformed since 2014 such that their military resources will be directed much more within NATO’s original area of responsibility: Europe and the Mediterranean. The drifting debate on NATO’s raison d’être, identity and strategic concept has thus already begun to focus away from out-of-area operations and back towards its collective defence origins.

NATO military spending

Much of the discussion on British defence policy around the 2015 general election and SDSR has focussed on whether or not the UK would commit to the highly symbolic spending level of 2% of GDP (a measure of national production) on its military. Chancellor George Osborne made this commitment publicly in July, although there is still external pagemuch discussioncall_made about how this spending level will be met.

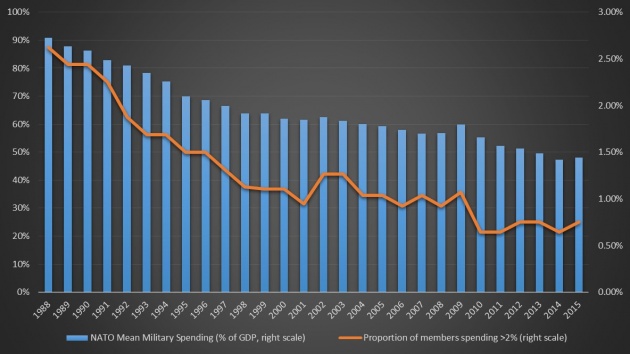

The 2% target is an entirely arbitrary figure without serious reference to the threats or responses that Europe considers realistic or the effectiveness with which such sums are spent. NATO has been promoting it for some time, largely in an attempt to encourage low-spending European members (current average: 1.4% of GDP) to close the spending gap with the high-spending US (about 3.5% of GDP). This has singularly failed. As Figure 1 shows, average spending has fallen almost every year since the end of the Cold War and three-quarters of all members now fail to meet the 2% threshold. Despite loud commitments to meeting this target at the external pageNATO Summit in Walescall_made a year ago, the post-2014 trend has been to stabilise military spending rather than to increase it.

Figure 1: NATO Military Spending as % of GDP, 1988-2015

As Malcolm Chalmers of the establishment defence think tank RUSI external pageputs itcall_made, “The Atlantic Alliance has done itself serious reputational damage by giving so much emphasis to a target that so few of its member states have managed to meet.” The 2% target thus undermines confidence between the US and its European allies. Whether or not the leading actors in NATO are yet willing to recognise it, the NATO 2% target is already a lost cause and ripe for re-evaluation against the actual capabilities that European states need to deter or defend against likely threats.

One of the strongest arguments for NATO is that it offers the genuine possibility of burden-sharing, including costs, through collective defence. Lest we forget, the size of the European economy (whether defined as the EU or European NATO) is slightly larger than that of the US, nearly double that of China, and ten times the size of Russia’s. While it spends a low proportion of its income on defence, European NATO still spends almost $300 billion per year on its combined military, much more than China and well over three times what Russia spends. As Table 1 shows, that spending translates into a very significant quantitative advantage in virtually every field of conventional military strength even without the addition of US forces.

Country/

Bloc

Active Personnel

Combat Aircraft

(4th Gen+)

Attack Helis

Active Main Battle Tanks

(3rd Gen+)

Frigates/

Destroyers/

Cruisers

Aircraft Carriers

Missile Subs

(SSBN/SSGN)

Attack Subs

(nuclear/diesel)

USA

1,400,000

2,800

990

2,800

90

10

18

54/00

European NATO

2,000,000

1,900

450

2,900

149

2

8

12/59

Russia

770,000

1,300

350

950+

25

1

19

17/16

China

2,350,000

850

230

700+

74

1

5

08/55

India

1,350,000

450

200

1,000

24

2

0

01/13

Note : Figures are estimates from several sources and include active personnel and equipment only. Most states have larger numbers of long-term stored main battle tanks of modern and older design.

Table 1: Personnel and Equipment Strengths of Major Militaries and Blocs

The UK is the largest single military spender within European NATO, with an annual defence budget of about $60 billion (£39 billion) or 20% of total. However, this does not go very far in European terms. British forces generally have a qualitative edge in equipment, training and deployability but, with the exception of the Naval Service, they constitute barely a tenth of European strength. Alone, the UK would still be a significant regional military power, with or without its nuclear weapons, but its capabilities would be miniscule compared to NATO or even Russia.

There is therefore a strong efficiency argument to be made for NATO membership: UK defence is potentially cheaper and more effective through coalition burden-sharing. However, without a focused idea of what NATO is defending against and a realistic assessment of what potential adversaries’ capabilities and strategic ambitions are, it is impossible for NATO to have a meaningful conversation about what that burden is and how it can fairly be shared. Focusing the debate on an arbitrary spending target and symbolic spending increases is a major distraction from such a conversation.

Alternatives to NATO?

If NATO did not exist, would the UK and its neighbours be forced to invent it? In the current context of European Union, probably not, since the CFSP covers much of the same ground and without NATO would probably be compelled to be a much stronger component of EU policy. Indeed, the messy overlap of EU and NATO security structures and policy means that there is a lot less certainty about the UK’s commitment to the defence of non-NATO EU member states like Sweden, Finland and Malta than there would be without NATO.

Yet this ignores two factors. The first is perhaps historical, that the EU would not have coalesced or expanded in the way it has without the security guarantees and common purpose that NATO has provided. The second is both historic and ongoing and refers to the trans-Atlantic alliance with the Unites States. NATO’s security guarantee during at least the Cold War was dependent on the massive overt and implicit US commitment to European defence at a time when European powers lacked both the resources and confidence to work together effectively. That is no longer the glue that binds European security cooperation. It certainly makes the ongoing alliance far more potent, for better and worse: most European states feel more secure; Russia feels more threatened.

Things look different from Washington, necessitating the question: does the United States need to talk about NATO? Only about 63,000 US military personnel, or less than 5% of total, are now based in Europe but the continent’s security and the sabre-rattling with Moscow is an increasing distraction from the Middle East and Western Pacific.

If NATO did not exist, would the United States be forced to invent it? It seems unlikely that it would in its current form, although it would be anomalous if Washington did not have some sort of alliance with the cluster of European democracies that is its biggest market. Apart from NATO, the United States has mutual defence agreements with virtually every democracy in the world, from the hemispheric commitments of the Rio Treaty to the Australia-New Zealand-US (ANZUS) Treaty to bilateral agreements with Japan, South Korea and the Philippines. True, most of these treaties were not made in the name of democracy, and there are many autocracies in the US sphere, but in Washington’s current web of military alliances post-ISAF NATO is but one among many.

What of the vaunted Special Relationship between the United States and the UK? While US generals have talked up the UK’s unique position of being able to deploy division-sized ground forces as well as ships and aircraft in US-led operations, this is more of a nice-to-have than a must-have for the US. The greater value of the relationship is likely to lie in privileged intelligence arrangements of which we know little. This includes the sharing of facilities in and intelligence from such outposts of the empire as Cyprus, Ascension Island and Diego Garcia, as well as the UK mainland. Given the controversies surrounding Anglo-American mass surveillance operations in the current decade, such arrangements might be a more obvious target of future Labour policy, rather than NATO per se, and potentially more damaging to trans-Atlantic relations.

It seems unlikely that either the United States or Europe would have forged an alliance as strong as NATO if it did not already exist in 1990. But it seems even less likely that the intimately linked societies of Europe and North American would not have some form of security relationship. It is less inevitable that NATO should expand to incorporate all of Eastern Europe, play a role in military operations outside of Europe or fund military forces disproportionate in size to those of neighbouring states. These are some of the questions that should be asked over the current term of the UK parliament. Whether there is the political courage or vision to try to answer those questions remains to be seen.