China's Economic Downturn: The Facts behind the Myths

13 Nov 2015

By Francois Godement for European Council on Foreign Relations (ECFR)

This article was external pageoriginallycall_made published by the external pageEuropean Council on Foreign Relationscall_made on 20 October 2015.

After years in which China’s economic hyper-growth was taken for granted and its technocrats were seen as unassailable, there has been a dramatic reversal in international sentiment. The Chinese economy is now widely believed to be faltering; in place of the “new normal” which Premier Li Keqiang has tried to project,[1] not to mention the former “Beijing Consensus”, a rather different “new consensus” is emerging. According to the prevailing wisdom, China is today struggling to deal with the simultaneous impact of several negative trends: overinvestment and overcapacity in several basic economic sectors, overborrowing by local governments, overstating of previous growth statistics, overvaluation of the Chinese yuan, and a coming demographic downturn.

China is not facing a deep-rooted economic crisis, however, but rather a crisis of expectations on the part of Chinese and international observers alike. There is truth in each of the trends identified by pessimists, but they are not new. Each of them, save the overvaluation of China’s currency, has been present for several years – and has been clearly recognised in Chinese economic debates. Indeed, the Chinese authorities had explicitly called for this slowdown, which started a year ago. None other than the former premier, Wen Jiabao, warned repeatedly at the end of his tenure that China’s growth path was “unsustainable”, and that the growth model had to change drastically. This kind of structural transition is the hardest course to navigate for any economy accustomed to the previous policies.

This paper will argue that the downturn should be seen as a sign that China has begun the transition from one economic model to another that is more consumption-driven and focused on service industries. Nevertheless the current state of the transition and the negative reaction it has provoked raise an important question: Is the process advanced enough that, with the proper blend of government steadfastness and encouragement, a new economy can replace the capital-intensive, export-oriented, and infrastructure-based model of the past? Or, as often happens to reform policies when their downside prevails in the short term over their upside, will the sense of crisis from the present market turmoil put a halt to the whole transition process? In that case, the familiar drivers of China’s hyper-growth – government control of the economy and of lending, the priority given to state-owned enterprises (SOEs) large-scale public works and infrastructure, and financial repression in the form of interest-rate gaps and currency manipulation – would reassert themselves.

Two other assumptions are accepted as part of the new consensus. One is that the slowdown in China – a country often considered as a driver, if not the driver, of the global economy – will precipitate a global downturn. This would not be unprecedented: in February 2007, a somersault by China’s stock markets provoked a short-lived storm of similar size on Wall Street and elsewhere. Never mind that the global economy’s actual exposure to Chinese exchanges back then was cited by almost no one. A psychological fear of contagion and its knock-on effects was enough to send markets into a tailspin.

But the psychological and the real links between China and other economies should be distinguished as far as possible. At present, just as uncertainty is the most deadly factor for domestic Chinese economic actors, there is little clarity about the likely effects of China’s downturn on other economies. Our thesis is that these effects have mostly been overestimated – but the ensuing losses, although limited in scope, can be very sharp where they apply.

The second assumption is that uncertainty about China’s economy will weaken China’s international diplomacy. China’s foreign policy has always had as a key goal to facilitate the country’s economic development. This has for a long time revolved around two priorities: defusing the criticism generated by China’s huge trade and current-account surplus, and translating China’s growing capacity to export or re-export capital into its own version of “soft power”. What would the consequences be if these two trends reversed themselves: if China was no longer the world’s major export force, and was hit by capital outflow just like other emerging economies? This would present a unique opportunity for developed consumer economies, with their low geopolitical risk and large market base, to seek out Chinese investment partnerships.

The choices that China is going to make in the coming months are huge, and will particularly impact other emerging economies. It will have to select a target exchange rate for the yuan, for example, choosing between financial stability that would help to legitimise China as a global stakeholder, or prioritising support for growth in a return to beggar-thy-neighbour policies. China might indulge in cut-throat price competition, or transition with slower growth to an economy that is no longer based on the same sectors.

To analyse the nature and consequences of the changes in the Chinese economy, we have structured what follows around a few basic questions:

•How deep is China’s slowdown, and is there an upside to the changes in the domestic economy?

•Is this slowdown the breakdown of a model, or a crisis arising from the transition to a new model?

•How much of an impact is China’s downturn having on the global economy? Are there identifiable winners and losers?

•What macroeconomic policies in China and Europe would be the best response to these developments?

How deep is China’s downturn?

China’s contrasting economic statistics point to a transition dilemma, more than to a financial crisis or a demand-led crisis. There are declines in the basic industries and sectors that experienced a bull run during the hyper-growth years, accompanied by a new growth pattern for consumption, service, and IT-related sectors that does not quite match this decline in absolute numbers.

Though China’s real GDP growth rate has steadily slowed in recent years, from 11.5 percent in early 2010 to 7 percent in the first half of 2015, and 6.9 percent in the third quarter, this average hides a more diverse reality. Within the country, the northern provinces are suffering a more severe downturn (Liaoning tops the list at 2.7 percent), while much of eastern and central China is still growing at a rate of above 8 percent.

In addition, some sectors of the economy have fared far worse than others. Steel and cement, which were growing at a rate of 25–30 percent in 2010, have entered negative territory since early 2015. Electricity dipped into negative territory in early 2015 and has only slightly rebounded since – however, this overwhelmingly reflects the demand from large state enterprises. Domestic consumption of coal fell 6 percent from May 2014 to May 2015, while imports shrank 38 percent in the same period; consumption, overall, is thought to be down by 13 percent. Rail freight statistics are also down, due to falling coal consumption.[2]

However, these declines do not reflect economic catastrophe, but China’s changing economic structure. These sectors were targeted for growth reduction due to overcapacity, while the bloated real estate and infrastructure sectors – which consume the most electricity – were often based on overborrowing by local governments.

The cutbacks in steel production, housing, and infrastructure projects are desirable parts of the transition process because of both steel overproduction and environmental concerns. China’s mammoth coal consumption is the world’s biggest climate-change headache. In 2013, China produced half the world’s steel – 779 million tonnes – and in the process consumed half a billion tonnes of coal, equivalent to 10.4 percent of China’s annual electricity production. [3] Energy efficiency had been in decline in Chinese industry, with as much as 38 percent of all energy wasted. Housing also suffers from overcapacity. Incredibly, as some have noted, China now has more residential space per capita than Spain, a country that has become a symbol of the real-estate bubble. It is highly likely that China’s previous GDP statistics included a large quantity of “bridges to nowhere” – unnecessary infrastructure projects catering to local interests.[4]

The sudden revaluation of the yuan coupled with wage increases and a slowdown in global trade has unquestionably hit China’s exports – particularly from the bottom-rung assembly plants. However, this trend is particularly visible to foreign visitors, and may therefore be overemphasised. The truth is that the same thing happened in 2008, and yet China’s export business picked up handsomely a year later.

Booming sectors

Some indices stand out for their continued rise despite the downturn. For the last five years, household income has increased faster than the overall economy. Since 2010, household income and wages have increased as a proportion of GDP, reversing a trend of two decades. Reflecting this, retail sales have kept rising, increasing by 10.5 percent in the first three quarters of 2015.[5] In the third quarter of 2015, consumption reached 58 percent of GDP, with investment slowing to 42 percent. The discrepancy with lower GDP growth rates can be explained by a fall in fixed-asset investment growth rates (from 15 percent in 2013 to slightly over 10 percent by September 2015). Gross fixed capital formation itself – tracking all savings, private and public – has decelerated. Low-end incomes have increased more than any other since 2011: rural and migrant wages have increased at a faster pace than urban wages, reducing inequality.[6] Labour scarcity has finally lifted the incomes of these groups. This, and the anti-corruption drive, may explain the shift in consumption patterns, away from luxury or premium brands that are often foreign, in favour of more popular domestic brands. Previously, high-end incomes were wildly underestimated because of “grey” income and corruption.

At the same time, the service sector, which had always lost out under China’s previous growth model, stands at 51.4 percent of GDP in 2015, with an 8.4 percent growth rate between January and September. Crucially, urban job creation has not decelerated with the downturn – 14 million new urban jobs were created in 2014, and a further 7.2 million in the first half of 2015. This means unemployment has not increased so far, although there are far more positions open for blue-collar workers than for college or university graduates. Private enterprises, which today command the lion’s share of exports and job creation, with far more return on capital than state enterprises, have considerably increased in numbers since 2012. While overall fixed-asset investment steadily decelerated in 2013 and 2014 (from a 21 percent growth rate to a 15 percent growth rate), investment by private enterprises is now growing faster (at 18.4 percent) than its public counterpart. This extends a trend that has been much discussed for the years up to 2012. [7]

Some sectors have boomed even more. Chief among them is the e-commerce sector, where China is arguably a world leader in terms of market share, if not in the technologies that support the sector: online retail sales boomed 36 percent in the first three quarters of 2015. Previously, China’s distribution was archaic; now it is leaping ahead, along with the logistics sector, to become the most efficient in the world. Whether this will create jobs or destroy them, and at what wage levels, is debatable. But there is no question that this trend towards competitive e-commerce, coupled with the huge drop in imported energy and raw materials, has resulted in a key feature of today’s Chinese economic climate: price deflation, which pushes down GDP.

Can these booming sectors be sustained despite the downturn? It is not certain: there is a slow convergence of all wage trends with the GDP growth rate, weakening the evidence for a continuing structural shift. Indeed, it remains to be seen what will happen in a new environment where lower growth is expected. It is also necessary to wind down inventory. For real estate, this is happening now, with an increase in home purchases from existing stocks rather than from new construction.

Foreign trade

The same contradictory picture applies to foreign trade. Much has been made of the decline in trade this year, but this applies to imports even more than exports (exports recorded their first real decline in August 2015).

Several factors make this decline less significant than it might appear. First, China is a huge importer of primary and raw materials, whose price has tumbled – from oil to the base materials used in construction and manufacturing (aluminium, lead, copper, etc.), and also, more recently, agricultural products, from sugar and cotton to soybean and grain.

Second, while the declining value of Chinese exports to Europe has been much cited, it is likely that volumes of exports are in fact still rising. China’s currency revaluation of the last three years – essentially due to the dollar peg – has lifted it above any other Asian currency, with a 25 percent gain on the euro in a year. This decreases the value of all imports, including goods in process (which go into re-exported manufactured goods) and is also reflected in a drop of export prices. The decline of Chinese exports to the European Union, for example, is even smaller in value (5 percent) than the impact of revaluation would be, given identical volumes. The slow growth of the European market, compounded by zero inflation, also exercises a downward pressure. Given the decreased prices for goods in process incorporated into those exports, it is likely that the volumes of exports to Europe have kept increasing. Steel exports to the European Union in fact went up 50 percent in 2014. Strikingly, overall Chinese export prices have stayed at the same level since mid-2012, whatever else is being said of wage rises and inflation.

Third, China is not ceding the market in lower-end manufacturing, even though the competitive pressures from other emerging economies are widely reported. True, some of China’s exports are rising on the technology scale. But, to cite some glaring examples, Chinese exports of textile yarns, fabrics, and related products are at least 50 percent higher than in 2010, exports of footwear are up more than 70 percent, and exports of furniture are up 100 percent in the same period.[8]

China’s transition to a service economy, and move away from massive construction and excess capacity in industries like steel production, does have an effect on the international economy. Perhaps the strongest argument to show that China is having a major downward impact globally is that it is clearly creating much less demand for products from abroad. From January to September 2015, China’s trade surplus reached a historic peak of $424 billion. The ratio of trade surplus to GDP for 2015 will likely be between 5.5 and 6 percent. This reverses the trend of earlier years towards a more balanced ratio, but it is not the portrait of an economy likely to tip over any time soon.

Much has been said and will be said of China’s unreliable statistics. From the figures cited above, particularly those for electricity production, some economists conclude that the fall in GDP has been much more severe than official statistics recognise. Some alternative measures use freight, electricity, or bank loans as proxies for the “real” GDP. They point as a precedent to 1998, when GDP growth was hyped at 8 percent while electricity production grew by only 0.4 percent. But today it is precisely these sectors that have seen a voluntary curtailing of production: relying on these measures exaggerates the slowdown. Underestimation is as likely in other areas – such as individual income, commercial, or service sector output – as overcounting used to be, due to unsold inventories in sectors such as steel or housing. Two recent in-depth studies have concluded that there are many snags in China’s economic reporting, but no overall intentional bias.[9] If anything, mistakes appear above all in the underreporting of growth in the real estate and service sectors.

Breakdown of a model or transition crisis?

However, even if the downturn points to a transition dilemma more than a financial crisis, there are two important factors that indicate trouble ahead for China.

First, the sentiment of economic actors has been growing increasingly negative, both in China and abroad. The move towards a larger role for private investment and consumption and for the market would not be problematic if it translated into a positive psychology. However, the mixed signals sent by various arms of government since the stock market’s fall on 15 June, and the resulting uncertainty, have caused a shift in outlook.

Indicators of sentiment since the June 2015 stock market reversal are mixed, but some point to a recent fall: for example, auto sales, which were still in slightly positive territory in the first six months of 2015, started to decline over the summer. And China’s leading Purchasing Managers’ Index (PMI), which tracks the forward decisions of manufacturers, declined between March and August, but moved back into positive territory in September. Analysts often neglect Chinese investor and consumer sentiment, which plays an important role in the economy, with a noticeable herd instinct. This is evident in stock market fluctuations, and in the attention generally paid to government decisions. But market psychology can also work against domestic economic trends, as in the 1997 Asian financial crisis. Then, China was not greatly affected directly in the first stage, because of stringent capital controls. But the change in mood of Chinese consumers brought growth down very quickly.

The second factor pointing to trouble for China is the direction, or perceived direction, of government policy. The lack of clarity on intentions – or a series of genuine oscillations and disagreements on policy – is hurting China’s economy.

The current government’s economic policy often rests on a refusal to make profound structural changes. Under President Xi Jinping, official policy has strengthened both the state and the private sector. It curtailed overextended sectors, and supported them to prevent a major downturn. It let the market steer the direction of financial stocks, and guided them itself. It appears that the current government has seen no harm in letting different policies apply to different economic sectors and issues.

Previous waves of Chinese economic reform eschewed liberalisation, leaving the state’s centralised control of the economy intact. The first generation of reforms, from 1978 to 2007, mostly produced winners. However, it also created new entrenched interests, in the form of those who profited from real estate and from reinvigorated state enterprises. The period from 1994 to 2007 was singularly successful in recentralising public finance, which had become fragmented, and creating strong state enterprises while handing over many activities to the private sector. As a result, “reform” in China has not been equated with market liberalisation or decentralisation in its recent history. The success of economic statecraft generated a belief in the invincibility of Chinese economic decision-making, which has indeed overcome many dark predictions about bottlenecks, stumbling blocks, and limits to growth.

The hesitation about the next steps has been evident ever since the second term of the Hu–Wen leadership (2003–2013). There was a slowdown of reforms, and a turn against the foreign enterprises which had taken over the bulk of Chinese exports. The government sought to cool off hyper-growth and prevent more bubbles, alternating this monetary tightening with support for key economic sectors. This “stop-and-go” policy has not changed much since the Xi–Li team took over.

Xi’s economic policy

The Xi–Li team’s economic policy intentions have been obscured by a flurry of technical and administrative reforms,[10] but there are three major developments that define current economic policy.

One is the move to make China a capital-exporting country. The current government has encouraged investment abroad by Chinese state enterprises, extending the existing “going out” policy that encouraged manufacturing firms to produce abroad. The partial liberalisation of the capital account, the launch of a bevy of overseas investment projects – publicised by the Silk Road, or One Belt, One Road, initiative, but by no means limited to it – and the encoragement of mass tourism abroad, with the attendant export of cash, were a sign of confidence on the part of the leadership. It may have believed that the current-account surplus was inexhaustible. In the past, the authorities bought foreign currency from Chinese exporters. This resulted in swelling foreign-currency reserves and increased the amount of Chinese currency in circulation, with the side effect of massive bubbles in China’s domestic economy. Now, the export of capital as an alternative means of balancing the current-account surplus avoids these side effects. It also offers an outlet for the basic industry and state infrastructure sector whose further development in China is no longer desirable. Last but not least, it is a tool of China’s much-vaunted new “soft power”.

Indeed, the second leg of Xi’s policy has been the bid for global responsibility via plans to include the yuan among the IMF’s reserve currencies, and to make it a free-floating international currency. Free convertibility would certainly enhance China’s financial might. But this has always been a tricky objective, much debated in China as it runs against previous mercantilist policy. The changing target dates reflect a fundamental hesitation on this policy. In fact, freeing capital controls and moving to a floating currency can only be implemented on two conditions. China’s banking sector must first be brought up to international standards, not only in prudential terms but also in terms of management skills. The cosy relationships with parts of China’s political and administrative system must be severed. These are daunting tasks that Japan largely failed to achieve in the late 1980s, and are a core element of the famous “mid-level income trap”, where countries that make the jump to middle-income level find it hard to achieve the high income levels of developed economies. While Xi is willing to clean up the system through anti-corruption drives, and encourages private initiative at the periphery, he clearly does not want to dismantle the Party-state nexus at the centre of the economy.

Third, the lack of direction in Xi’s economic policy springs from his dualistic conception of China’s economy. Under this, two sectors – the public economy and a huge informal and shadow banking sector – can indefinitely coexist side by side. This may be based on Xi’s experience as Party secretary of Zhejiang province, home to China’s liveliest private entrepreneurs. They have filled the gaps in the state economy and public financing of the economy, occasionally subverting them through shadow financing schemes. The twin policies of the Xi–Li team – statist, rules-led, and even jingoistic, but also open to much “non-public” development – are best understood from this perspective. Tough reforms and marketisation of the state economy seem less necessary to the leadership, as it sees China as growing successfully with a dual economy.

The Xi–Li team’s support for an e-commerce economy and even e-banking is part of this dualistic economic policy. The former leapfrogs China’s archaic distribution sector, boosted by low labour costs. The latter creates interest rate competition for the official banking sector, weakening the margins which have always allowed the inefficient banking system to prosper at the expense of China’s savers and borrowers.

This two-track approach harks back to the first era of reforms under Deng Xiaoping – and Xi’s father, Xi Zhongxun, a high-ranking Party official who was behind the creation of the Special Economic Zones (SEZs), where foreign investment was encouraged. Instead of a frontal attack on the strongholds of the socialist economy, Deng surrounded them with new developments on the periphery. Strikingly, the Zhejiang model differs both from Shanghai – where a state economy clearly prevails, including in the financial sector – and from the so-called Guangdong model where foreign and private enterprises are far more prevalent. The approach of the Deng reform era, when different sectors of China’s economy could be managed very differently, is now much harder to apply, as there is a need for unified rules and a level playing field that go hand-in-hand with the nationwide transport infrastructure and IT connectivity.

In addition, Xi has launched an anti-corruption campaign that works like a Swiss army knife – useful for targeting political rivals within the regime, as well as rooting out vested interests that resist change. Today, the emphasis is more on the latter goal, that of disciplining China’s local governments and economic strongholds. The oil, electricity, and coal sectors have been purged, as have the transport sector and several provinces (Shanxi and Guizhou top the list, now joined by Fujian). At the last count, 120 vice minister-level cadres had been ensnared.

For a long time, there was an almost total absence of targets for the anti-corruption campaign in the financial sector, which probably reflected the lack of major reforms planned in this field. The stock market shock of June 2015 has changed this. While the judicial organs are going after “speculators” and deterring the sale of blocks of shares, several top financial cadres have been investigated by the Party’s anti-corruption team: the president of CITIC, the most emblematic public finance institution of China’s reform era; and the vice president of the securities regulatory commission, which serves as watchdog for the stock market. Still, in the short term, the anti-corruption drive has hampered initiative by officials, and is no substitute for a clear direction on economic reform.

Internal contradictions

There are important policy differences among China’s key economic decision-making bodies. The central bank’s adherence to a currency internationalisation and capital liberalisation scheme is well known, if not very influential. The National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC), the government body in charge of economic strategy, seemed to lose influence in the first year of Xi’s tenure. It has now regained its position, and is the clearing house for the Party-state’s diverse interests.

Decision-making has therefore arrived at a series of contradictions, forcing the authorities to pull back from their reform policies. Cooling off real estate and infrastructure spending depresses activity and encourages price deflation, which is fuelled by international trends. In recent months, the public financing of new infrastructure projects has again been encouraged. Credit restrictions in the real-estate sector (for example, discouraging multiple home ownership) have been eased. The Shanghai–Hong Kong Stock Connect programme (which allows for cross-border investment in shares from each market) has eased capital controls in the key zone of Shanghai, facilitating capital outflows in recent months. The opening of dollar accounts within China’s banking system has been authorised, and has been taken up on a massive scale – reportedly to the tune of $650 billion – as firms and individuals seek to protect themselves from a potential yuan devaluation.[11]

On 11 August, the central bank attempted a liberalisation of the currency, but was forced to return to an undeclared peg as the yuan rapidly lost value. The Chinese authorities had repeatedly raised the reserve obligations on banks and financial institutions, in an effort to cool the creation of new credit, but were forced to reverse this in order to maintain economic growth. Interest rates should in fact go down – driven both by low global interest rates and by the increasing competition for deposits by new e-banking entities. But lowering interest rates would cut into banks’ profit margins, and make it harder to subsidise state firms and quasi-public firms that are expanding abroad. A devaluation of the currency makes sense after its steep rise, but this would provoke sharp international criticism, as China is again recording a mammoth trade surplus.

When one does not want to address contradictions, it is tempting to deny their existence. The reality is that China’s economic policy is now based on incompatible goals. Until recently, the government was pursuing two goals: a gradual loosening of external capital controls, and keeping the yuan anchored to the dollar. High interest rates in China, in effect much higher than in other large economies even at times of massive monetary creation, were a recognition of the impossibility of maintaining an independent interest rate policy given these other two goals. But now, by accident more than by design, China is aiming simultaneously at all three goals – dispensing with external capital controls, pegging its currency to the dollar, and pursuing an autonomous interest rate policy.[12] It has now in effect repegged the currency, and vowed to stay the course. On 29 September, China’s financial institutions went a step further, intervening massively in the offshore currency market and in effect closing the gap between the offshore and onshore yuan. It is also pursuing the third goal, of lowering effective interest rates, furthered by the – correct – decision to create bonds for local governments, which had previously been legally prevented from borrowing.

This is a dangerous situation, perhaps akin to that prevailing in East and Southeast Asia prior to the 1997 financial crisis. Then, currency pegs, liberalisation of external accounts, and attempts at driving the economy through interest rates brought down the house.

However, China won’t go the way of Asia in 1997. There are various steps the government could take to mitigate the downturn. Currency reserves are immense and fungible, as are the various levels of debt. The rise in dollar account deposits could be countered by a heavy government tax – this would be unpopular but would stem the move to dollar savings. Recently, the vice president of the People’s Bank of China, the central bank, advocated a substantial Tobin tax on short-term capital outflows that would be a move in the direction of taxing flows to other currencies.[13] In spite of its commitment to stable exchange rates, if the government reimposes formal or informal capital controls, a step-by-step and incremental devaluation would again be perfectly possible. International justifications could easily be found: the quantitative easing in Japan and Europe, and the rise in US federal interest rates, which creates a massive pull effect towards the dollar. Finally, infrastructure spending can still reflate the nominal GDP.

However, most of these measures are short term and run counter to the objective of free-market reform. The change of model outlined at the beginning of this brief requires China to bite the bullet, accept a temporarily much lower rate of growth, and link its capital markets to the outside world in order to increase competitiveness.

In earlier days, the Deng leadership’s strategy was often to run down obstacles by speeding up and generalising reforms. It is much harder today for two reasons, one objective and one subjective: first, after three decades of fast growth, there are many more vested interests in China – from property owners to wage earners. The country’s top leader (and possibly many of his colleagues) is pragmatic but suffused with a sense of China’s success and ability to ride out storms without the need for fundamental reform. In fact, this is the precise image – “a big vessel hitting rough seas” – that Xi communicated to his US audience at the start of his September 2015 visit. His most trusted lieutenant, Wang Qishan, is the leader who popularised Alexis de Tocqueville among China’s leadership in 2012, drawing from him the lesson that reform is always a dangerous path to start on.

It is possible that the current government’s preference for minute administrative changes, and the top-level concentration of policy decisions, have resulted in an improper sequencing of reform. Freeing up some capital controls before liberalising the exchange rate or picking the moment of a major stock market shock to start a depegging of the currency both seem odd, at least in retrospect. Some of the same lack of sequencing seems to have happened with the One Belt, One Road policy initiative – a surge in uncoordinated projects, and many bids for the cash that is supposed to be available.

If that were the case, it would mean that China’s transition process is now plagued by the inconveniences of a top-down personal system, where there is not enough capacity for arbitration and planning beneath the level of the top leader. This is perhaps not so much a case of Xi refusing to carry out reforms, as a messy transition process from one economic system to another that fosters uncertainty and widespread anxiety.

China’s downturn and the world economy

The influence of the Chinese stock market on the global economy is widely overestimated. Its impact is essentially psychological, and it is the violence of its falls (in 2007 and 2015) after long periods of exuberance that has drawn the attention of foreign punters. Only two years ago, the same markets were going through a bearish trend that was completely uncoupled from global markets.

Two common misconceptions about China’s links to the global economy should be dispelled. The first is that China’s stock markets drive global equity trends. Their large capitalisation is tempered by the fact that only 30 percent of the shares issued by state firms – which constitute 80 percent of this capitalisation – are tradable and liquid, the rest being crossholdings mostly held by other state institutions. In addition, the stock markets have historically been largely closed to foreigners. Although backchannels have been established that allow ingenious foreigners to invest in “A” shares (previously reserved for Chinese citizens), these channels are illegal. The government has built up various “qualified investor” schemes that serve as a filter, requiring time and previous investment, for foreigners to hold shares. The recently established Shanghai–Hong Kong Stock Connect programme is the only significant channel that links the Chinese stock market to outside markets – chiefly, Hong Kong.

The second misconception – that China is the locomotive for global growth – explains the psychological fallout from its stock market fluctuations. In reality, though China is the largest component of global growth, its ability to pull others is limited and localised. An economy whose trade and current-account balance is consistently positive does not promote growth outside its own borders. China’s capacity as an external lender matters much more, especially vis-à-vis the United States and some energy- and raw material-producing economies, but this can be seen as a mere balancing process. While China’s outward investment has grown in size, and now balances inward direct investment, it does not yet create an overall surplus.

True, the reduction in the relative size of China’s current-account surplus (from 10 percent to 2.7 percent of GDP between 2010 and 2014) has returned capital in the form of flows to China’s partners, though the current explosion might reverse the trend again. The very recent rise in the trade surplus, however, is partly balanced by a smaller rise in capital outflow – mostly hot money in anticipation of a deeper devaluation of the yuan. Chinese firms, especially major state firms in key sectors (airlines, telecoms, transport) had unexpectedly become large borrowers on the international market, at a reported total of $550 billion by mid-2015. Given that the expectation is now for a rising dollar, they have an incentive to draw down their dollar debt now, while the new peg holds up the yuan. China matters by itself, of course, but its pull effect on the global economy should not be exaggerated. The price deflation that China has caused for many consumer products boosts standards of living worldwide – and a Chinese recession or devaluation would only increase this boost to consumer markets and commodity-importing economies. Of course, the picture is completely different for producer economies and emerging economies competing with China in the same export markets. The Chinese slowdown is not without impacts, but they are very different depending on where one stands. Overall, this undermines the accepted narrative about the international transfer of power to emerging countries.

Trade dependence

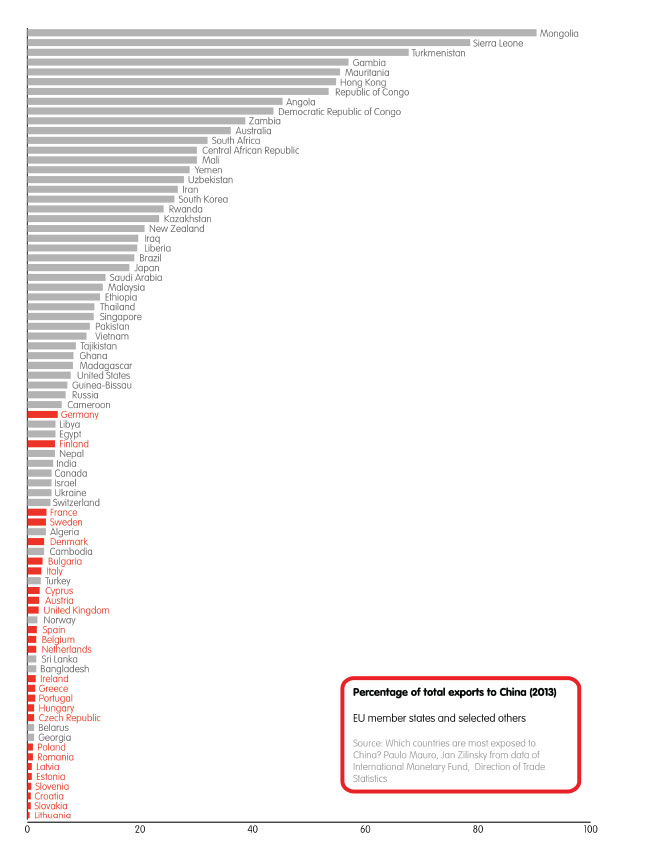

China’s linkages with the rest of the world can be analysed through trade dependence figures – the percentage of each country’s exports that go to China. This gives a very diverse picture, with some surprises. Mongolia and Sierra Leone lead the pack (over 90 percent of exports going to China), with several energy-rich or mining African states following, joined farther down the line by Australia and Brazil (36 percent and 19 percent, respectively). East Asian powerhouses that export both final and in-process goods to China come next, with South Korea at 26 percent and Japan at 18 percent. The US is above average at 13 percent, in the upper range for the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) economies. Europe deserves a special mention, as only one country, Germany, places above 5 percent (5.4 percent, to be precise), with another nine countries at between 2 and 5 percent. The rest (24 countries, including non-EU members) are below 2 percent, with the United Kingdom at the top of this list and Lithuania bottom at 0.4 percent. In sum, Europe, which is China’s leading export market, is less oriented towards China for its own exports than any other region, save Latin America.

Trade in value-added (TiVA) goods is even more significant, but the figures are harder to gather.[14] This data shows a reduced Chinese deficit with East Asian economies, and a reduced surplus with Western developed economies. The foreign content of China’s overall exports stood at 33 percent in 2009, a figure higher than the OECD average and consistent with China’s deep integration into the global value chain.

Do these deep links mean more impact from a Chinese slowdown? Quite the contrary. Certainly, China’s slowdown and price deflation are disastrous for the world’s producers of energy and raw materials. They have a positive impact for those who invest in China and import its goods, though not for those who export to China. Other emerging economies may engage in competitive devaluation: for the time being, almost all currencies have devalued relative to the yuan. But we should not confuse cause with consequence: Brazil and Venezuela are being hit by their own dependence on commodities, not by China’s importance for the global economy. China’s difficulties still matter less than the huge shortfall for oil producers and emerging economies that have entered a phase of currency war.

Benefits from China’s slowdown

Where China’s slowdown does have a major impact abroad, this impact is mixed. For consumer markets such as Europe, which are neither producers of primary material nor large exporters to China, the benefits from a Chinese slowdown are twofold: the downward trend in primary material prices benefits all importers; and the reduced price of Chinese exports is a boon to living standards.

There are two caveats, however: first, indebted economies (whether public or private debt) will find the debt burden even less sustainable if price deflation sets in. Price deflation from China and commodity producers, and a rise in interest rates from the Fed, would be a double whammy for these indebted economies. Second, economic difficulties in China may incite aggressive price-dumping – displacing domestic producers in other countries.[15] The first negative effect is likely to hit European economies with high debt levels. The second is hitting emerging economies that compete with China on the same range of exports.

All in all, the potential effects of a Chinese downturn are mixed. To take Europe as an example, the effects on Eastern Europe will be mostly positive (lower primary prices and cheaper consumer products from China, while exports to China are not significant). The effects are negative for Germany (which is more energy efficient, and relies on China as an export market). Southern European economies (to which we add France) have much to fear from price deflation that will increase their relative debt burden.

Much of the above, however, is based on a static picture and not a dynamic scenario, where China and its partners take different courses of action that change the outcome. A recent analysis outlined the dilemma for Europe.[16] On the surface, external trends have been extremely positive for the eurozone: the boom in exports to third markets (the US, the UK, and Canada), as well as the reduction in import cost factors, have put the eurozone’s current account deeply in the black (€115 billion for the first half of 2015). In fact, Germany now has a 9 percent ratio of trade surplus to GDP, while the Netherlands has a ratio of 11 percent. Since 2011, it is global exports alone that have lifted the eurozone recession into a modest and uneven growth. However, that lift came from exports to the US and UK, not from trade with China or other emerging countries. The Chinese slowdown, and the simultaneous difficulties for emerging economies and commodity producers, signals that trading with these countries will not improve Europe’s growth prospects. Since the end of the 2001-2014 commodity supercycle, the eurozone has benefited from improved terms of trade. It must now channel some of these proceeds towards domestic investment and consumption, its public debt notwithstanding. In that sense, China’s slowdown highlights the importance of the eurozone’s domestic economic policies over the drive during recent years to export its way out of stagnation.

Policy implications

China can still choose to be part of the solution rather than a problem. Speeding up its move to a service- and market-driven, consumer-oriented economy will lessen the risks of another investment bubble resulting in unsustainable debt (so far, even the largest estimates, at 300 percent of GDP, are still serviceable). So long as this transition is not channelled through nationalist economic policies, it would also balance China’s external accounts and lessen the pressure for currency revaluation. If China makes this choice, it will drive growth in developed economies, if no longer in developing economies that are primary producers.

On the other hand, turning the clock back with government stimulus for traditional industries, thereby increasing the already-high capital cost of China’s growth, and returning to a mercantilist policy resting on a lower yuan and the reimposition of capital controls would have two consequences. One is a pile-up of debt inside China. The second is an international controversy over this policy, most likely originating in other emerging economies.

So far, China is staying the course, sticking to a very minor devaluation, and mostly preserving the partial lifting of capital controls it has carried out in recent years. To achieve the third phase of transition – market-driven interest rates – China must move towards a currency that is less and less managed, if not free-floating. This cannot be achieved without a much deeper reform and marketisation programme than the myriad of technical measures announced over the last two years. This choice is the most important question facing the Chinese leadership.

Europe’s China policy

All this has direct consequences for European policy towards China.

First, when capital outflows, intended or spontaneous, occur from China, they open a window of opportunity for Europe. The search for opportunities by Chinese investors is not fulfilled either by China, with its excess capacity, or by Silk Road projects in narrow Eurasian markets with high geopolitical risk and a slump in energy and metals prices. Safer returns are to be found in European markets, dwarfing anything on the Eurasian routes. More liberal economies – chiefly, the UK and Sweden – and Eastern European economies are right to seek China as a main funder of infrastructure projects, albeit with Chinese suppliers. The terms for long-term financing have never been so good; China’s supply prices, thanks to deflation and excess capacities, are becoming almost unbeatable; and the quality gap with Western supply has decreased in all but the very top technologies.

Europeans must act together if they are to acquire any leverage with China. In doing so, they may well explore formulas based on ownership or leasing rather than lending – requiring risk-taking by those who bring capital, rather than by borrowers. This is the only way that the profitability of projects can be assessed. Three complementary building blocks of this policy are: the so-called Juncker plan or European Fund for Strategic Investments (EFSI), a widening of the formula to include more possibilities of public-private partnership in ownership and management, and a bilateral investment treaty with China.

Second, the turn in China’s economy towards services and the changing trends in consumption – away from luxury brands and towards cost-sensitive products – means that any investment or free-trade negotiation with China must include the opening of the service sector, and of Chinese firms. China’s negotiators have been closed to this in the past, but criticism about a ballooning trade surplus might make them more flexible. There is also less likelihood than ever of China forming a united trade front with other emerging economies, as they are locked in deep competition. Finally, there is now a capital outflow from China in any case. This may help Europe make the case for a more balanced negotiation.

European objectives remain the same: breaking into areas of China’s economy beyond the free exchange of goods – the ownership of firms, the service sector, and public procurement. This can be achieved through a bilateral investment treaty, but China is currently seeking a free-trade agreement, primarily to lock in its status as a market economy and to avoid further anti-dumping measures. The goals of each side are not symmetrical, and any negotiation must recognise both. A deal whereby Europe would participate more in China’s new economy while opening itself to the older Chinese sectors seems like a win-win proposition. Such a European opening would also apply to other actors, such as Japanese and Korean firms and investment funds. However, none of this will be possible if the new European Union competence over investment, acquired through the Lisbon Treaty, is not implemented. So far, many member states are trying their luck through separate bilateral negotiations with China, ignoring the fact that, if better coordinated, they might have more leverage with Beijing and bring about a change in the rules.

Acknowledgements

This brief has benefited from comments on its first draft by Anthony Dworkin and Agatha Kratz. Under pressure of time, it has been edited by Anthony, Hannah Stone and Gareth Davies, who have helped to clarify the economic arguments. I am also thankful to Abigaël Vasselier, our Asia programme coordinator, who made it possible to take the necessary time for this exercise, and Richard Speight, who designed the graphics and helped promote this paper.

Notes

[1] See his September 2015 speech at the World Economic Forum in Dalian.

[2] In 2009, for example, coal made up 48 percent of all rail cargo transport in China. See Mark C. Thurber and Richard K. Morse (eds.), The Global Coal Market: Supplying the Major Fuel for Emerging Economies(Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2015), pp. 657–658.

[3] “China as the World’s Largest Steel Producer”, Research Institute of Economy, Trade & Industry, 11 July 2014, available at http://www.rieti.go.jp/en/china/14071101.html.

[4] The term “bridges to nowhere” was used in Japan in the 1990s when the government launched stimulus packages that catered to local interests.

[5] For this and subsequent figures for 2015, see China’s National Bureau of Statistics, “Overall Economic Development was Stable in the First Three Quarters of 2015”, 19 October 2015, available at http://www.stats.gov.cn/english/PressRelease/201510/t20151019_1257742.html.

[6] “China Economic Update – June 2015”, The World Bank, p. 11, available at http://www.worldbank.org/en/country/china/publication/china-economic-update-july-2015.

[7] Nicholas Lardy, Markets Over Mao: The Rise of Private Business in China (Washington, DC: Peterson Institute for International Economics, 2014).

[8] Statistics from Trading Economics, available at http://www.tradingeconomics.com/china/exports-of-textile-yarn-fabrics-and-related-prod.

[9] See Carsten A. Holz, “The Quality of China’s GDP Statistics”, Stanford Center for International Development, Stanford University, 27 November 2013, available at https://www.nottingham.ac.uk/gep/documents/china/conferences/2013-14/ningbo/holz.pdf; and Daniel H. Rosen & Beibei Bao, Broken Abacus? A More Accurate Gauge of China’s Economy (Washington, DC/Lanham: Center for Strategic & International Studies/Rowman & Littlefield, 2015).

[10] These were heralded by a mammoth Party resolution in November 2013, while Xi Jinping has vaunted, for 2015, the completion of “108 reform tasks with 370 reform outcomes”. See “Full Transcript: Interview With Chinese President Xi Jinping”, the Wall Street Journal, 22 September 2015, available at http://www.wsj.com/articles/full-transcript-interview-with-chinese-president-xi-jinping-1442894700.

[11] To put this in perspective, total bank deposits in China are estimated at $15 trillion. An IMF study estimates that full lifting of capital controls would result in much higher outward than inward flows.

[12] Among macroeconomic laws, few are as recognised as the Mundell triangle, named for Robert Mundell, the Nobel prizewinning economist who ironically has long advised the Chinese government and is a Green Card holder in Beijing. It is also called the “impossible trinity”: a country cannot simultaneously conduct an autonomous interest rate policy, peg its currency, and dispense with external capital controls.

[13] Economist James Tobin originally developed the idea of a tax on currency movements to curb high-frequency trading. Yi Gang made the same suggestion in the CCP’s journal Qiushi in January 2014. See “PBOC vice-governor Yi Gang suggests Tobin tax on foreign exchange”, Agence France-Presse, 5 January 2014, available at http://www.scmp.com/business/economy/article/1397784/pboc-vice-governor-yi-gang-suggests-tobin-tax-foreign-exchange.

[14] The OECD–WTO database only extends to 2011, with cross-data analysis available only to 2009.

[15] A recent study – sponsored by an alliance of European manufacturers – warns of dire consequences for employment in Europe if China is granted market economy status, i.e. allowing it to avoid most anti-dumping charges. The figures quoted seem to be a stretch, but would be credible if China carried out monetary devaluation. See Robert E. Scott and Xiao Jiang, “Unilateral Grant of Market Economy Status to China Would Put Millions of EU Jobs at Risk”, Economic Policy Institute, 18 September 2015, available at external pagehttp://www.epi.org/publication/eu-jobs-at-risk/call_made.

[16] Simon Tilford, “Global slowdown: The eurozone to reap what it has sown?”, CER Bulletin, Centre for European Reform, 21 September 2015, available at http://us2.campaign-archive2.com/?u=e5ac52c2f8bd1b249ef1a8d18&id=fcd338b47a&e=dcaf61543a.