Arms Procurement (I): The Political-Military Framework

16 Nov 2015

By Martin Zapfe, Michael Haas for Center for Security Studies (CSS)

With Russia’s annexation of Crimea and the open advances of the so-called “Islamic State” (IS) during 2014, the ability of European states to ensure their security is being scrutinized with a new sense of urgency. In the medium term, one crucial element in this context is the procurement of armaments, especially of main weapons systems such as combat aircraft and warships. The underlying structures and processes are, in principle, comparable across all European states – regardless of whether they are NATO or EU members or not.

This analysis deals with the politico-military framework for future arms procurement in Europe. At its core are two questions: What are the basic structural problems of European arms procurement, and in which areas might conditions still be favorable for closer European cooperation? Our accompanying analysis goes one step further and looks at the dynamics of current and future armaments programs alongside the implications of military-technological developments for arms procurement.

In the past, high hopes were frequently placed in cooperation projects and the “Europeanization” of both arms procurement and the weapons industry – and nearly every time, those expectations have been disappointed. This is unlikely to change fundamentally. One factor that applies to all aspects of European arms procurement is that governments remain sovereign, and decide what they wish to buy and with whom to cooperate. Thus, arms procurement in Europe will continue to be determined by national concerns for the foreseeable future. While some steps towards more Europeanization of arms procurement have been taken, they will likely only return results in the medium to long term. Furthermore, any tentative progress will most likely be achieved via armed forces and the arms industry.

Challenges of Arms Procurement

It is important to sketch the basic parameters of arms procurement in Europe. The arms industry is not mainly driven by the logic of economic efficiency. Its first, and most fundamental task, is to serve as a reliable source of equipment supplies for the armies of individual states. Accordingly, security of supply and technical superiority have always been – and still remain – conceptually more important than economic efficiency. At the same time, defense spending is subject to a great deal of domestic scrutiny, and the financial determinants have been becoming more constrained over the decades, irrespective of whether defense budgets in individual European states are rising or falling.

The reason for this is the so-called “defense economic problem”: The rapidly increasing technical complexity of modern weapons systems requires states to maintain huge research and development (R&D) capacities, in turn continuously increasing the price of weapons systems – for high-tech defense goods, average inflation is often around 10 per cent per year. Since national defense budgets are not increasing proportionally, and in many cases have decreased substantially, fewer weapons systems are being purchased. However, in extreme cases, fewer purchases hardly results in any savings, since fixed R&D investments and production costs cause the unit price to rise. This is especially problematic for Western countries, whose defense spending is relatively low when compared with their economic power, although their armies remain high-tech by global standards.

The desire to break out of this vicious circle is the fundamental economic motivation for inter-state cooperation in arms procurement. The core problems of cooperation become clear when analyzing the classic market actors in arms procurement – sellers, buyers, and regulators.

For buyers, closer cooperation between states is meant to enhance the efficiency of their procurement. For instance, R&D costs can be shouldered jointly, and unit quantities increased, to attain economies of scale. Among the best-known multinational cooperation projects for developing and producing sophisticated weapons systems are the Panavia Tornado (involving three project nations) and the Eurofighter Typhoon (four nations). These types of projects not only provide a long-term framework for cooperation between national defense industries; they also require harmonization of military capability planning, and as such are the most publicly visible symbols of multilateral cooperation. But even here, the constellation of interests among European purchasers is not uniformly “European”: smaller member states in particular, that lack a substantial armaments base of their own, often prefer to purchase armaments from the US and are less interested in a consolidated European market. While a desire to avoid committing to complex and expensive multinational projects plays a role here, the decisive factor (more often than not) is the desire to further cement a close alliance with the US.

One of the fundamental conditions for inter-state cooperation is that various national military requirements should at least be compatible. In Europe, it is mainly NATO and the EU that promote more harmonization of military requirements. Within NATO, the Defense Planning Process is supposed to encourage the harmonization of defense planning; in the EU framework, the European Defence Agency (EDA), founded in 2004, has a similar role. High hopes had been attached to the EDA in particular. However, the results so far have disappointed even its most ardent advocates. The agency is tightly controlled by its member states, which have shown little interest so far in seeing it become more independent and active. Despite decades of military cooperation within NATO and the EU, European states continue to go about defense planning in a largely uncoordinated manner. This is particularly true for land-based systems. For instance, Poland, France, and Germany currently develop and procure most of their land vehicles largely uncoordinated, and overwhelmingly from national producers.

Suppliers have traditionally been government-owned or semi-state industries. Because they were exempt from the rules of the European common market for over half a century, these industries largely remain structured along national lines. Substantial consolidation only emerged at the beginning of the last decade – the Airbus Group and MBDA (a company specializing in guided missiles) being among the best-known examples. This development was largely restricted, however, to the R&D-intensive aerospace industry. The European industry for ground and naval defense systems, however, remains highly fragmented. Advocates hope that further consolidation will result in a reduction of excess capacities and redundancies. Critics note the emergence of European monopolies in an environment with insufficient competition, resulting in positions of unhealthy, politically uncontrollable market power.

Overall, the EU’s efforts to promote consolidation of the industry into a European Defence Technological and Industrial Base (EDTIB) have shown few results. The interests of states with strong defense industries are too disparate to those who have none, with the former seeming to be insufficiently prepared to jeopardize their own jobs and interests in favor of consolidated industries. Ambitious EU plans thus do not seem promising, and the EU will unlikely evolve from its important advocacy role for the time being.

With regard to the regulation of arms procurement, the picture is different. For decades, this has essentially consisted of national protectionist measures. It was only in 2009 that the EU’s “defense package” forced an expansion of the single market to include defense products – notably, as a compromise package that included numerous important exceptions. It is true that the governmental process of awarding arms contracts, which had still been a largely national affair, was constrained to some degree, and the decades-old practice of excluding all arms deals from the European single market ended. Nevertheless, the two EU guidelines included in the package acknowledge the continuing reality of national protectionism, explicitly allow cooperation in major projects without competition, and tend to assume a creeping Europeanization of the awarding of weapons contracts over the long run. Accordingly, those aspects of armaments deals that have long been criticized, but simply underscore the political nature of arms procurement, will continue to require attention. Both the frequently inefficient division of work packages in accordance with the share of funding contributed by individual states in cooperation projects (juste retour), and ubiquitous offset deals, will be more regulated but not prevented in the foreseeable future.

This is all the more true since, for the foreseeable future, arms exports are not conceivable without such arrangements. Moreover, in this context, the critically important legislation for exports to non-EU states remains a strictly national affair, constituting a substantial obstacle for any multinational cooperation. Significant differences remain between arms-exporting countries in terms of the strategic and moral aspects of arms exports – especially since European weapons systems and the countries that use them are often direct competitors on the export market. However, as long as profitable orders within Europe remain rare and most states refrain from directly subsidizing the arms industry, exports are increasingly the most profitable source of income for the weapons-producing industry. A binding harmonization of export rules therefore remains off the table, given the deep-seated political differences between European governments.

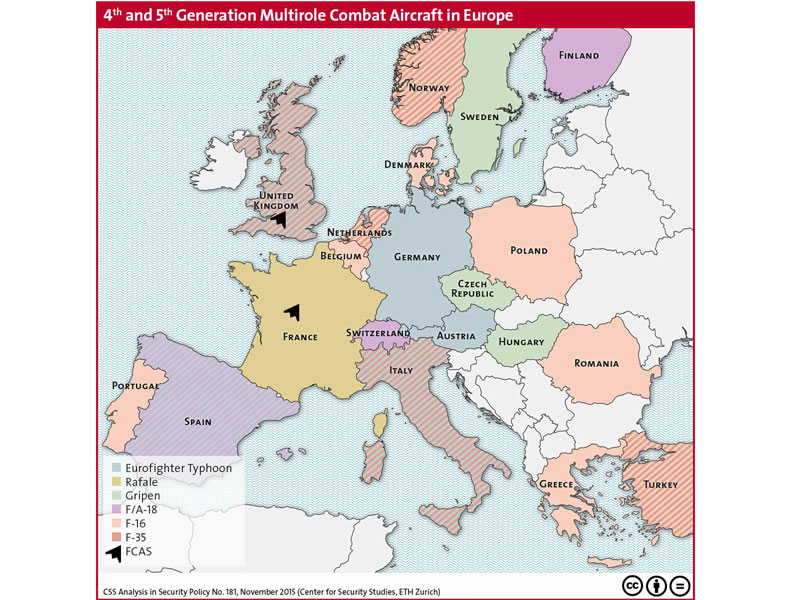

Map: 4th and 5th Generation Multirole Combat Aircraft in Europe.

Consolidation through the Backdoor?

Overall, some important steps towards a regulated European defense market have been taken, which may produce better results over time. Regarding the EU’s role as a defense market regulator, though, it appears that the scope for legal measures may largely be exhausted for now. Other developments on both the buyer and the seller side – specifically, military and industrial policy dynamics – may be more promising and possibly more important in the short term.

Military Dynamics

Institutional attempts by NATO and the EU to harmonize capability requirements have so far remained ineffective. More promising may be projects to jointly use existing weapons systems, and to create interdependencies among national armed forces through shared maintenance, and the further upgrading of these systems. At least in this regard, the political-military zeitgeist appears favorable, especially in the case of NATO.

Russia’s annexation of Crimea, the war in Ukraine, and the looming prospect of a casus foederis (invocation of Article V of the North Atlantic Treaty) on the southeastern perimeter of the alliance have caused NATO and its member states to refocus on planning for alliance defense – despite so-called “hybrid” threats, these are essentially military preparations for higher-intensity conventional warfare. These scenarios tend to require capabilities that involve both high-tech and heavy equipment. High-tech, since the air-based weapons platforms and guided munitions, that would be critical in case of hostilities, typically involve a huge R&D effort. Heavy, since NATO’s rapid reaction forces would be mainly centered on mechanized and armored task forces. Current pooling and sharing models, however, are patterned on the expectation of lower-intensity conflicts, and do not offer sufficient impulses for shared procurement programs – a situation that is unlikely to change anytime soon.

The reorientation of European security policies in 2014 has thus resulted in a more promising outlook for R&D-heavy cooperation projects, even after the expiration of production for European customers of the current large-scale armaments programs such as the Eurofighter Typhoon, the A400M transport aircraft, or the Tiger attack helicopter. This especially applies to the various technological prototypes for armed and unarmed European drones (see the accompanying analysis) and, to a lesser extent, to the development of next-generation combat vehicles. Smaller Eastern European states in particular have demonstrated a renewed interest in European land systems, but lack funding for the procurement of new vehicles as well as for maintenance and training installations. This opens up new prospects not only for joint procurement, but also for heretofore overlooked options such as leasing main weapons systems, a possibility that was last properly discussed in the 1970s, although ISAF leased equipment for its operation in Afghanistan during the 2000s. In this way, larger states can lease material from their inventories to Eastern European NATO members, support them on maintenance and training, and thus create the basis for later cooperation in arms procurement. Taking recourse to conventional defense could thus provide new impulses for shared procurement programs between European states.

Industry Dynamics

The defense industry, too, has recently made some moderate progress towards consolidation. Mergers and takeovers in the arms business do not take place without the assent of the governments in question – but neither must they necessarily be initiated by governments. Here, some leeway remains for further convergence, even without a governmental “master plan” for the integration of the arms industry.

While the European aerospace industry was rapidly consolidated into a handful of mostly transnational market leaders during the 2000s, there have been no substantial adjustments since then. Major corporations such as Thales, the Airbus Group, or BAE Systems remain strongly interlinked by mutual ownership of shares and joint ventures. However, the leading national defense industries remain essentially distinct. After political resistance in 2011 prevented the fusion of the Airbus Group and BAE Systems, which had been touted as the “big push” for the European aerospace business, no major changes are expected in this area for now. The market for naval and land-based weapons systems is much more fragmented. Land-based vehicles in particular require less R&D; also, the vicious circle of the “defense economic problem” has had less effect here in pushing states towards cooperation – a situation that is compounded by the fear of losing defense-related jobs. Existing and planned procurement programs for land-based systems show clearly that, even today, the inclination towards procurement from national suppliers remains unchanged.

Against this background, the merger of land systems producers Nexter (France) and KMW (Germany), agreed in August 2015, is significant. Despite the concerns of some observers, there is currently no danger of a quasi-monopoly; instead, the deal appears to have created a transnational corporation that continues to face strong competition, including from other European companies. Certainly, national interests remain dominant, and the French government continues to safeguard its interests with a “golden share”, including with respect to future export markets. Nevertheless, this step is more in line with the laws of the market than earlier mergers, and the actors in question continue to hold out the prospect of additional acquisitions. Considering the importance of these two companies for the production of main battle tanks, such a step sends a strong signal.

It is possible that this fusion will have a trickle-down effect on the fragmented landscape of land-systems producers. The obstacles are high, and in important states such as Poland, a reverse trend is discernible, as the procurement of land-based systems has been re-nationalized across the entire spectrum of vehicle types. However, if European governments could find the courage to leave the initiative to market forces, and shape the dynamic of market consolidation more constructively, a more efficient defense industry could result in the long run.

Slow Ahead?

From the political-military point of view, there is little reason to expect decisive breakthroughs in European armaments procurement. The defense industry will never be subject to pure economic logic in a comparable way to the “civilian” branches of the economy. Whether or not additional tentative progress will be possible depends on a number of factors, including whether the “conventional turn” in the wake of the Ukraine crisis will form a sustainable basis both for new joint long-term procurement projects, and for innovative short-term approaches – for instance, the leasing model, which has been hitherto viewed askance by some governments, or shared maintenance of main weapons systems. This will primarily be possible in the framework of NATO. Additional initiatives towards consolidation of the industrial base are primarily expected to come from the industry itself. In the long term, all of these developments can contribute to more efficient weapons procurement at a manageable political cost. In any case, any changes will be difficult to implement without the consent of the European governments – and certainly impossible to implement against their wishes.