The Ideological Conflict Project: Theoretical and Methodological Foundations

29 Dec 2015

By Thomas Homer-Dixon, Steven Mock for Centre for International Governance Innovation (CIGI)

This article is an excerpt of a paper external pageoriginally publishedcall_made by the external pageCentre for International Governance Innovation (CIGI)call_made on 9 July 2015. The full paper can be accessed from our Digital Library.

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

We present in this paper the theoretical and methodological foundations of the Ideological Conflict Project (ICP).

Ideology is important to conflict. Shared beliefs create a sense of group identity, specify targets of hostility and enable coordinated action. Understanding ideology is key to effective conflict resolution and management. But up to now, ideology has been poorly understood. It is presumed to be something abstract or irrational, therefore best disregarded in the search for concrete explanations and solutions. Those who do pay attention to ideology tend to offer simple explanations for its role, often due to incorrect assumptions about the relationship between ideas and material objects, between mind and body and between individuals and the groups to which they belong. Political theorists examine the effect of ideology on society, while political psychologists examine either the biological, cognitive or social forces that shape individual beliefs. While all of these approaches contain insight, each explanation alone is too simple to yield effective predictions useful in dealing with real-world conflict situations.

Using complexity theory, we can account for the multiplicity of processes that combine to generate ideologies. At the same time, any effort to understand human behaviour must take into consideration the peculiar properties of the human mind, and so engage with cognitive science. Combining these approaches, we have developed two methods that can be applied toward clarifying the role of ideology in conflict situations:

- Cognitive-Affective Mapping (CAM): a method for depicting beliefs as networks of concepts that interact in a manner akin to the neural networks that process them. It offers a quick and easy means for depicting ideas as data, including the emotions attached to concepts that are crucial to decision making. CAM can be used in negotiation to locate points of difference and misunderstanding in the belief systems of disputants, as well as emotionally loaded concepts that could be hidden points of tension or, alternately, creative pathways for compromise. It can also be used to map the beliefs that are important to a group identity, so as to predict the effect of group membership on individual behaviour.

- Ideological State Space: a series of methods for classifying ideologies according to the fundamental dimensions on which they differ. This allows us to visualize how ideologies cluster around certain “attractors,” offering explanations for why seemingly unrelated or even contradictory positions bundle into coherent ideologies, how belief systems co-evolve in relation to one another, why they are resistant to change and why change can be so rapid and dramatic when it does happen. The latter phenomenon can be well-represented using the principles of catastrophe theory to model the rapid psychological changes that occur in groups during eruptions of violent conflict.

The ICP has developed these methods into a powerful set of analytical tools that researchers and practitioners can use to understand, manage and resolve conflict.

INTRODUCTION

Nelson Mandela was known to compare violent conflict to a bonfire: the wood is persistent economic inequality, ethnic and religious differences are the gasoline, and the spark needed to ignite it is the irresponsible actions of selfinterested politicians.[1]

This metaphor warns against any temptation to reduce conflict to a single cause, whether material deprivation, religious or nationalist fanaticism, or the manipulations of political elites. Anyone seeking a single general cause to conflict is more likely imposing his or her own theoretical or ideological predilections than capturing the essence of the phenomenon. It is not even enough to attribute conflict to a list of “necessary conditions.” Like a bonfire, it is not merely the presence of certain factors, but a particular interaction between them, that leads to the outbreak of violence.

The bonfire metaphor also captures the non-linear character of conflict. A person can pile wood, pour gasoline and increase heat continuously; at one point, fire appears where there was no fire the moment before, and once it has it can spread rapidly. So too does conflict often appear as a sudden, unpredictable event, even when it was the product of gradual underlying forces. And once this tipping point has been reached, it is not easy to reverse. Removing the spark that started a fire will not put it out; the fire remains, generating the heat that feeds it. So too with conflict, even when instigating conditions have been removed or corrected, the ideas and emotions they activate cause violence to take on a life of its own. This could be why the metaphor of a spreading fire is often used by commentators to describe an escalating conflict, or by revolutionaries to describe the spread of a social movement.

What is the role of ideas in conflict? This is the question that the ICP aims to address. But this seemingly simple question contains some of the most intractable problems in both the cognitive and social sciences. Ideas exist in minds; they are systems of mental processes that generate consciousness, emotion and agency in ways we are only beginning to understand. Yet conflict, in the sense that we use the term, is collective behaviour, demanding an understanding of social systems such as identity, culture and institutions. Explaining the intricate internal workings and structure of any one of these systems is difficult enough. We are tasked with explaining a phenomenon that is the product of multi-level interactions between them.

Conflict, broadly defined, refers to any state of protracted dispute between parties over divergent principles or interests. Although the parties in question need not be collectivities, these tend to be the focus in examinations of political conflict — which is to say, conflict relating to the exercise of social power. And although conflict need not necessarily be violent — involving the use or threat of coercive force with the potential to cause harm — violent conflicts tend to be of paramount concern and therefore dominate discussion.

Any meaningful explanation of how and why people engage in violent social conflict, when rational self-interest would nearly always seem to favour individual nonparticipation, must make some reference to ideology, which we define as a system of ideas, beliefs and values used to understand, justify or challenge a particular political and/or economic order. Shared beliefs and emotions are needed to give groups a sense of identity, specify targets of hostility, legitimize aggression and enable coordinated action.

But overall, the role of ideology in violent inter-group conflict remains poorly understood. In the 1960s and 1970s, scholars in the realist tradition introduced rational choice and equilibrium models to explain interactions between states. Such models, which continue to dominate the study of politics and international relations, tend to frame conflict in purely material terms, with conflict management policy focused on manipulation of material incentives. Realism tends to consider state interactions to be a direct result of the relative distribution of military strength and government’s sole focus on survival and the maximization of relative gains in power. Realism largely neglects the importance of ideas, beliefs, values and norms because actors’ interests are assumed to be exogenous and fixed over time. Hence, the question of how interests are formed based on values and beliefs about the world is not addressed. Approaches in the liberal tradition that emerged in the 1970s have broadened the theoretical “tool box” for explaining patterns of conflict and cooperation in two ways. First, liberal approaches acknowledge a wider range of political actors aside from national governments, including domestic and international civil society. Second, liberalism recognizes that actors’ interests may go beyond military security to also include economic prosperity. Neo-liberal institutionalism highlights that conflicts can be prevented and cooperation can occur if institutions are designed in a way that leverages common interests and thus makes everyone better off (Keohane 1984). Yet, liberalism still falls short of explaining the origins of specific interests and preferences; again, these ideational factors are assumed to be exogenous. Both realist and liberal approaches stay within a material ontology and are therefore able to draw on microeconomic methodology, including cost-benefit analysis, game theory and utilitarianism, in their analysis of sources of conflict. The notion of political actors as rational decision makers driven by material interests remains dominant.

Nevertheless, it is rare for realist and liberal scholars to deny the importance of ideas in driving human actions. (Finnemore and Sikkink 1998) emphasize that early realists recognized the enabling and restricting effects of ideas and norms. Obviously, people fight for things they feel strongly about, and beliefs, values and emotions are usually explicit in the way that parties understand and justify conflict. R. O. Keohane (2001), a neo-liberal institutionalist, points out how international relations theory needs to be extended to account for the crucial influence of values and beliefs in creating effective and normatively acceptable institutions. But even if one is prepared to acknowledge the causal significance of ideational factors, if these are seen as too complex to understand and measure, they are likely to be treated as random noise rather than structured signals, as opposed to actors’ observable behaviour and tractable material interests.

Despite the elusiveness of ideational factors and the methodological difficulties associated with their measurement, an ideational turn occurred in the study of international politics in the 1980s. In the school of social constructivism, ideational factors became the central object of analysis. Social constructivism is a broad label that subsumes multiple distinct approaches to analyzing and explaining conflict and security, but the uniting principle across these approaches is that ideas must be recognized as important causal factors in political behaviour, along with the intersubjective constructs generated by ideas such as nationality, ethnicity, religion, class and ideology.

Social constructivism assumes that identities and interests are endogenous and contingent on social practices and relations situated in time and space. Social constructivists aim to identify underlying reasons for political actions that are logically prior to the utilitarian models employed by rational choice theorists. Nevertheless, an excessive and exclusive focus on ideas can lead to overemphasizing their causal significance over the material realities to which they refer and with which they must interact. Therefore, J. G. Ruggie (1998, 33) claims, a combination of both material and ideational factors constrain actors’ decisions: “Constructivists hold the view that the building blocks of international reality are ideational as well as material; that ideational factors have normative as well as instrumental dimensions; that they express not only individual but also collective intentionality; and that the meaning and significance of ideational factors are not independent of time and place.”

But beyond the sensible premise that ideas matter, specific theories as to how they matter — how exactly intersubjective constructs form, change and impact collective behaviour — are notoriously difficult to verify or falsify. Certain social constructivist scholars have taken important steps in this direction, however. M. Finnemore and K. Sikkink (1998), for example, examine the formation, diffusion and the influence of norms on behaviour in international politics. A norm is defined as a standard of appropriate behaviour for actors with a given identity (ibid., 891). While norms are far from prescribing behaviour, normative change over time is considered able to alter actors’ interests. Nevertheless, instead of providing a full account of how exactly norms drive behaviour, Finnemore and Sikkink refer back to rational choice theory and suggest a reconciliation of their theory on norms with utilitarian approaches, rather than a replacement.

J. Boli and G. M. Thomas (1999) examine the role of culture in world politics, arguing that international nongovernmental organizations function as carriers of world culture and work to diffuse cultural norms and values. They define culture as a “set of fundamental principles and models, mainly ontological and cognitive in character, defining the nature and purposes of social actors and actions” (ibid., 14). The diffusion of world culture, they argue, enables the emergence of a world polity, an international society with a cultural and legal world order that operates increasingly independently from states and shapes actors’ actions, identities and interests. However, their explanation as to how exactly culture shapes actors’ identities and interests and the substantial content of world culture remains rather simplistic. As M. E. Keck and K. Sikkink (1998, 210) point out, the notion of a developing world polity based on shared world culture negates the existence and uncertain outcomes of deep struggles over power and meaning in the process of normative change. In other words, Boli and Thomas have little to say about the conflicts arising along the way to a universal world culture — conflicts that stem from competing principles and models.

D. C. Thomas (2001) analyzes the fall of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR) to illustrate the crucial role of norms and identity concepts in effecting radical political change. He argues that the USSR signed the Helsinki Agreement on Human Rights in 1975 in order to gain legitimacy among Western European states whose identity was characterized to some degree by their adherence to human rights principles. A shift in state identity incentivized the USSR to comply with the Helsinki norms, although they are not legally binding because the USSR’s new identity implied that full acceptance by the West became more important than continuation of the communist system. Thomas (2001) concludes that constructivist theory with its focus on norms, identity and the endogenous formation of interests provides better explanation for the USSR’s behaviour than liberal theory with its focus on exogenous, utilitarian interests. Nevertheless, his analysis draws little general conclusions on ideational conflicts, beyond the general principle that ideas matter.

In summary, the study of conflict in international relations is balanced between, on the one hand, a realist-materialist ethos that tends to marginalize, if not discount, the role of ideas in favour of more easily tractable factors, and on the other hand, a social constructivist challenge that gives due emphasis to ideas but is not yet sufficiently integrated to generate a general model of exactly how ideas factor in to political behaviour. Acknowledgement on the part of rational choice theorists that the interests that define interest-seeking behaviour are not fixed properties, but rather can vary according to a context defined by differing culture and values, demands a method to account for culture and values as rigorously as one might account for more easily measurable material factors. And while the social constructivist emphasis that ideas matter is sensible on its face, it calls for a better, more concrete sense of just what “ideas” are. Particularly when these ideas take the form of norms and institutions — properties of groups rather than of individuals — a careful scientific understanding of how they form, where they are located and how they are diffused between the individual and the collective is needed to avoid reifying groups and attributing them with mysterious forms of agency. While social constructivist researchers have made significant progress in theorizing about the crucial rule of ideas in explaining political actions and conflicts between groups of actors, the specific mechanisms by which ideas come to be understood as properties of institutions such as states or organizations, or forms of community such as nations or ethnic groups and the ways in which such ideas can gain agency in social relations are still not fully illuminated. Our methods aim to build on the basic insights of social constructivism to meet these hitherto unaddressed challenges.

Classifying Conflict Stakes

In an effort to integrate the strengths of these approaches, M. Raymond and D. Welch (2014) developed a method of classifying conflicts by isolating the conflict “stake” — a specific object of dispute, the reason why parties care enough to engage in conflict — and determining whether that stake is “material” or “ideational.” Although any conflict stake is ultimately an idea in the sense that it is a concept contained within the mind, this approach offers a way to show how the dynamics of conflict will be impacted by the character of that idea; whether it refers to a concrete and therefore measurable property or to something more abstract, idiosyncratic and culture-dependent.

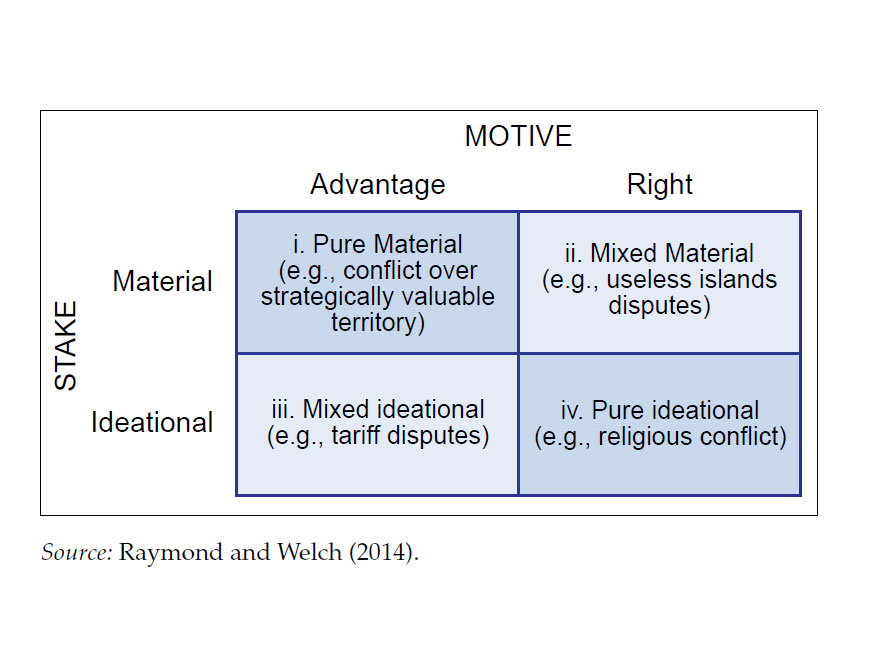

The first stage in classifying conflicts involves locating the conflict stake across two dimensions:

- whether the stake (the object over which conflict occurs) is material (concrete) or ideational (abstractsymbolic); and

- whether the motive (why combatants care about the object) is material (advantage) or ideational (right). These two dimensions yield four conflict types, identified in Figure 1.

Such a typology conveys more information than rational choice models alone, simply by accounting for types of conflict where ideational stakes and motives are causal factors, enabling recognition of cases where ideational strategies for conflict resolution might be effective. That said, it will be a rare case where a conflict stake or motive is purely ideational with no material aspect or purely material with no ideational aspect. Conflict motive and stake is, in practice, rarely easily classifiable according to such a simple scheme, as there might be multiple stakes and mixed motives involved. Furthermore, not all ideas have the same effect on conflict behaviour. Therefore, this scheme goes on to distinguish three types of ideational stakes: identity (concerning group membership and symbols that define a group), justice (relating to the rightful allocation of goods, both tangible and non-tangible), and rule or institution (relating to the rules that govern social interactions). Again, these must be understood as ideal types. Ideational stakes in actual conflict situations are more likely to involve a combination of identity, justice and rule components and different actors will emphasize different aspects of an ideational stake at different times. Of course, the specific symbolic content of what is important to a group’s identity, what is considered just and what makes for an intelligible and reasonable social rule will depend on each disputant’s culture.

When all of these complications are considered — the ideal-typical character of the categories, the possibility of multiple, mixed and mismatched motives and stakes and the context-dependent nature of cultural content, added to the fact that conflicts may involve more than two disputants with further opportunity for mismatch — we are left with more possible conflict types than are easily tractable. Nonetheless, the exercise of focusing on the character of conflict stakes has the immediate value of bringing ideas to the centre of the study of conflict.

The notion that conflict is shaped in part by the combatants’ understanding of what they are fighting over seems straightforward on its face. But this classification scheme offers means to test the intuition that conflicts may differ depending on whether they pertain to concrete measurable objects such as territory or resources, or more abstract psychological objects such as culture or religion.

However, questions as to exactly how ideas affect conflict remain to be answered. Merely counting the number of possible conflict types expressible by this classification scheme explains little, as not all combinations are likely to be useful or equally probable. Some conflict types will be found more often than others in examination of real-world cases. Further work is therefore needed to develop this framework into a predictive model, useful for informing practical policies for conflict resolution. For example, it is widely assumed that conflicts over material stakes that are concrete and measurable, such as territory or resources, are easier to resolve amicably through negotiation and compromise, while conflicts over abstract ideational stakes, such as identity or religion, tend to be more intractable. While this is a plausible hypothesis, there is already evidence to suggest that it is at best an oversimplification, if not a self-fulfilling belief stemming from the inability to adequately disentangle and measure ideational factors, causing them to appear indivisible. A early study undertaken by a group of CIGI Junior Fellows (Caverhill-Godkewitsch et al. 2012), in which this classification scheme was applied to a number of current and historical cases, suggested a more complicated picture, including instances where the introduction of notions of identity, justice and legitimacy to an otherwise material conflict improved prospects for conflict resolution.

Consider, for example, conflict between Mexican drug cartels and the Mexican state between 2000 and 2012. Although both sides had been known to use certain symbols of religion and culture, the connection between these and the core stake of the conflict was at best superficial. Rather, the stakes — wealth and control of the state — make this as close as one can imagine to being a purely material conflict. But therein lies the problem; a non-state actor that employs extra-legal means, especially violence, to strictly material ends is by definition criminal and illegitimate. When the National Action Party came to power under Vincente Fox in 2000, interrupting seven decades of rule by the Institutional Revolutionary Party, it was on a platform of overturning corrupt clientelist networks, including those that prevailed between the state and drug cartels, a policy that continued under Fox’s successor, Felipe Calderón. Although this policy led to a dramatic increase in violence, it could not easily be reversed, as any accommodation to the interests of a criminal organization would compromise the principle of rule of law in Mexico. This would not have been the case if the violence served a cause that was not strictly material, but rather could be understood as a matter of justice, identity or legitimacy. Compromise, or at least negotiation, would be easier to justify with an indigenous or ethnic minority group seeking cultural rights, or a political movement seeking to change state institutions according to an alternative conception of social justice, such as, for example, the Zapatista Army of National Liberation.[2]

Another example can be found in the conflict that led to the secession and independence of South Sudan. So long as this conflict was perceived by the Sudanese state as a material issue — retaining sovereignty over territory, along with the human and material resources it contained — there was little basis for compromise over the nationstate’s territorial integrity. But when Sudanese identity, as understood by the state, changed from being civic and secular to one based around Islamic culture, religion and law, a narrative allowing for the succession of the south on the basis of its different ethnic and religious character became more palatable.

These cases may be exceptional, and the hypothesis that abstract ideational factors tend to exacerbate conflict may still hold as a general rule. But it is a rule that must be subjected to more rigorous testing. And even if it stands, the existence of such outliers highlights the need for better methods for unpacking the role of ideology in conflict dynamics on a case-by-case basis.

Background to the Study of Ideology[3]

For the first half of the twentieth century, the study of ideology was the domain of historians and political theorists who examined belief systems thought to have had significant social impact. But with the rise of behaviouralist approaches to political science after World War II, particularly in the United States, scholars, using quantitative methods to measure political attitudes, found that real-world belief systems tended to be more varied and fluid than fixed terms such as “liberal,” “conservative,” “fascist” and “communist” implied. They concluded that ideological attachment was less significant than had previously been assumed, and ideology was devalued as a legitimate topic of study. It came to be seen pejoratively as an irrational and therefore largely unfathomable obstacle to rational calculation that only confounded preferred material and strategic explanations of political behaviour (Converse 1964; Jost 2006).

The study of ideology has been revived somewhat over the past two decades, although research remains fragmented. Positivist political science in the United States tends to focus on factors that determine an individual’s ideological outlook, treating ideology as a dependent variable. These factors include genes (Hatemi et al. 2011) and brain physiology (Amodio et al. 2007; Kanai et al. 2011; Chiao et al. 2009), as well as the social and psychological variables modelled by Systems-Justification Theory (Jost 2009), Moral Foundations Theory (Haidt 2001; 2007; 2012) and Terror Management Theory (Greenberg et al. 1990). Conversely, approaches grounded in sociology and anthropology and in the critical theory prevalent in European scholarship view ideology as an independent variable shaping political power, discourse and institutions. These bodies of work include Critical Discourse Analysis associated with the work of N. Fairclough (2001), R. Wodak and M. Meyer (2009), and T. van Dijk (1995; 1998); poststructuralist approaches such as those of S. Žižek (1994), E. Laclau (1997) and A. Norval (2000); and the morphological approach developed by M. Freeden (1996; 2003).

There remains a need for an approach that can integrate these disparate insights on the causes and effects of ideological attachment, into a comprehensive model that bridges disciplines and levels of analysis. At present, theorists who examine the causes and determinants of ideological attachment at one level — genetic, physiological, psychological, cognitive or social — tend to ignore other levels of analysis, as well as, crucially, interactions between factors at different levels. In fact, no factor is independent, and the true determinants of ideology bridge all levels through complex cross-scale interactions. Theorists also tend to assume simple mechanisms of causation. This is true both of those who examine the psychological and social determinants of ideological adoption and those who examine the function of ideology in shaping personality and society. In fact, causation is multidirectional, involving feedback effects between these two sets of processes. What’s more, one can often detect normative judgements that call into question the objectivity of these endeavours. Different approaches have the tendency, and at times even the intention, to subtly elevate either conservative or, more often, liberal ideologies as superior; more evolved as opposed to primitive, more proactive as opposed to reactive or more integrated as opposed to narrow. A truly comprehensive approach must directly confront these ethical questions. While remaining primarily analytical — seeking to better understand past and existing ideologies and processes of ideological change — it must be prepared to acknowledge and address questions of what distinguishes a good, functional or constructive ideology from a bad, dysfunctional or destructive one.

Complexity and Cognition

The principles and methods of complexity theory provide us with the means to develop such tools. Complexity theory describes a body of concepts suited to explaining how interaction between densely connected systems, often operating at different levels of analysis, can generate emergent properties and behaviours. It initially emerged from research in mathematics, physics, computer science, systems engineering and meteorology. More recently, ecology has made important contributions, and researchers now apply complexity to systems as diverse as fresh-water lakes, immune systems and financial markets (Beinhocker 2011; Michell 2009; Strogatz 1994).

Efforts to apply complexity theory to social phenomena have thus far relied mainly on analogies to processes observed in physics and ecology. Consider, for example, a classic illustration of complex animal behaviour: a murmuration of starlings. The flock appears to move as a whole according to a graceful pattern, yet this pattern is not contained in the mind of any individual bird. Each individual merely follows a set of simple rules of conduct in response to adjacent birds, with the complex pattern emerging from collective adherence to these simple rules. So too could it be said that humans following simple rules — say, a drive to maximize material well-being and sense of security around those who are culturally similar — will generate political constructs that function as a unit such as nations or states. Another example is the use of epidemiology models to show how ideas can spread across social networks in ways similar to how a virus spreads in a population.

Such analogies have proven insightful, generating knowledge about the nature of social behaviour that would otherwise be difficult to conceptualize. But if we are to take this approach beyond the level of metaphor — even useful metaphor — and apply it to practical situations, we must acknowledge the limits of these analogies as well as their insights. Humans are not birds; we can hold in our minds images of our selves and our communities, and conduct ourselves according to those images. Humans are not viruses; we do not adopt ideas passively the way we catch diseases, but wilfully embrace them. And humans are not a bonfire. A bonfire does not choose whether to burn. When a certain set of conditions are met relating to the presence of oxygen, fuel and heat, a fire will catch. But in the case of conflict, as in all such examples of collective human action, there is choice involved. And these choices — to conform to group behaviour, to embrace an idea, to participate in violence — are personal and emotional: I will follow an army or join the revolution; I will adopt a new ideology or vote for a different political party; I am prepared to change deeply held beliefs and risk disrupting my social order; I am willing to risk being killed or severely beaten, to put my family at risk or to overcome my aversion to inflicting harm on others.

What makes social phenomena different from physical and non-human biological systems is the involvement of a peculiar sort of complex system: the human mind, with its unique capacity for abstract representational thought and consequent properties of consciousness, identity and agency. Any useful method for understanding social behaviour must account for the human mind and what is known about how human minds work. This requires direct engagement with cognitive science, the multidisciplinary study of mind and intelligence.

We recognize that a statement so categorical will be controversial, so it is important that we clarify what we mean by it to reassure that we are not advocating a kind of psychological reductionism whereby social behaviour and dynamics can be explained solely and entirely with reference to the individual human mind. On the contrary, it should be clear that we recognize social structures as sui generis realities that are the emergent products of the interactions of systems at multiple levels, including systems of social communication and systems observable in the material environment. But the sine qua non of any social construct — the only irreducible component without which intersubjective belief could not exist — is a mind capable of abstract representational thought. So, while other levels of analysis are undoubtedly needed to fully explain social phenomena, any explanation that stands in contradiction to how human minds work must necessarily be wrong. Therefore, correct understanding of how human minds work must be factored into any working model.

Cognitive science has developed rich models of the psychological and neural processes involved in perception, problem solving, learning and emotion, but up to now these have been used mainly to describe phenomena that operate within the individual. They have only rarely been applied to social phenomena such as inter-group conflict. Bridging the social and cognitive sciences requires difficult collaboration between disciplines as diverse as neuroscience, psychology, artificial intelligence, linguistics, anthropology, philosophy, sociology, political science, economics and history, which operate with different methods, terms and background assumptions. But such collaboration is necessary, as the mobilization of groups of people to engage in collective action must involve dense interaction between systems of social communication and systems of individual cognition. The concepts, beliefs and values that make up political ideologies ultimately reside in individual human minds. Yet, they are created, shared and changed by and across social groups. Comprehensive understanding of political behaviour demands an approach capable of exploring links both “up” and “down” across molecular/neurological, cognitive/psychological and social/institutional levels of analysis.

Four concepts drawn from cognitive science are particularly important to understanding ideology and its role in political behaviour: mental representation, coherence, motivated inference and neuroplasticity:

- Mental Representation: Every belief or idea derives from the basic ability, unique to the human species, to create and manipulate images in our minds that stand for objects in the external world, whether we are immediately perceiving these objects or not. While it may be beyond our current abilities to precisely determine every neural process that contributes to creating a particular mental representation, it must nonetheless be understood that ideas and emotions are ultimately brain processes and thus should be examined as objects in nature rather than as abstract or mystical properties.

- Coherence: Just as a multiplicity of neural processes interact to generate mental representation, so too do multiple mental representations interact to create a belief. Each mental representation leads to the activation of others that are logically and/ or emotionally related according to a stable overall pattern. If, for whatever reason, the pattern is rendered unstable by means of an illogical or emotionally incoherent association, connections and valences in the system will shift and adjust until stability is restored.

- Motivated Inference: A process that distorts reasoning in favour of maintaining cognitive and emotional coherence, it occurs when a mental representation is so integral to the stability of a belief system it is conflated with an external fact. This leads to a selective weighing of evidence that tends to disregard information that reacts incoherently with the favoured representation.

- Neuroplasticity: While it is accepted that the brain is the source of all behaviours that make up the social environment, it is also true that the social environment can affect the structure of the brain. If mental representations are ultimately brain processes, then changes to one’s mind instigated by inputs from the social environment that alter coherent patterns of thought must be understood as physical changes to the architecture of the brain that can have profound and durable significance.

Varieties of Complexity

Complexity, in the scientific sense of the term, arises from the multiplicity of causal processes that result from dense interaction between dynamic systems. A system is an assemblage of elements — matter, energy and connective processes — that through their interaction produce a whole distinct from the sum of its parts, yet to which each part contributes. A system is considered complex, as opposed to merely complicated, if elements have a measure of latitude as to how they interact with their environment and with other elements of the system. The result is that changes to the behaviour of individual parts can have disproportionate effects on the whole, a phenomenon referred to as “non-linearity.” Small causes do not always produce small effects; large causes do not always produce large effects (Menck et al. 2013): power grids, arrays of coupled lasers and the Amazon rainforest are all characterized by multi-stability. The likelihood that these systems will remain in the most desirable of their many stable states depends on their stability against significant perturbations, particularly in a state space populated by undesirable states. Here we claim that the traditional linearization-based approach to stability is too local to adequately assess how stable a state is. Instead, we quantify it in terms of basin stability, a new measure related to the volume of the basin of attraction. Basin stability is non-local, non-linear and easily applicable, even to high-dimensional systems. It provides a long-soughtafter explanation for the surprisingly regular topologies of neural networks and power grids, which have eluded theoretical description based solely on linear stability. We anticipate that basin stability will provide a powerful tool for complex systems studies, including the assessment of multi-stable climatic tipping elements. This is the result of feedback effects: systems of circular causality, where the effects of one set of processes serve as causes of others and vice versa, forming a circuit or loop. This includes negative feedbacks, which keep systems in states of equilibrium despite whatever pressures and perturbations they might be subject to, and positive feedbacks, whereby relatively small pressures and perturbations can trigger chain reactions that disrupt systems or push them into new equilibrium states. These processes cause complex systems undergo critical transitions, sudden shifts or “flips” between equilibrium (Bertuglia and Vaio 2005; Scheffer 2009).

Consider, by way of illustration, a system such as a vehicle engine, which is complicated insofar as it consists of multiple components that must interact in a particular way for it to perform its function. But it is not complex, in that the manner in which each component functions and interacts is fully determined — if any one element fails to act in the prescribed manner the system as a whole ceases to perform its designated function. In contrast, in a complex system such as the flock of starlings, the sudden death of an individual bird will not severely affect the flock as a whole. However, the choice of direction made by any individual bird, even if it remains within the established parameters of behaviour, may affect the choices made by adjacent birds, leading to feedback effects that could alter the shape and direction of the entire flock.

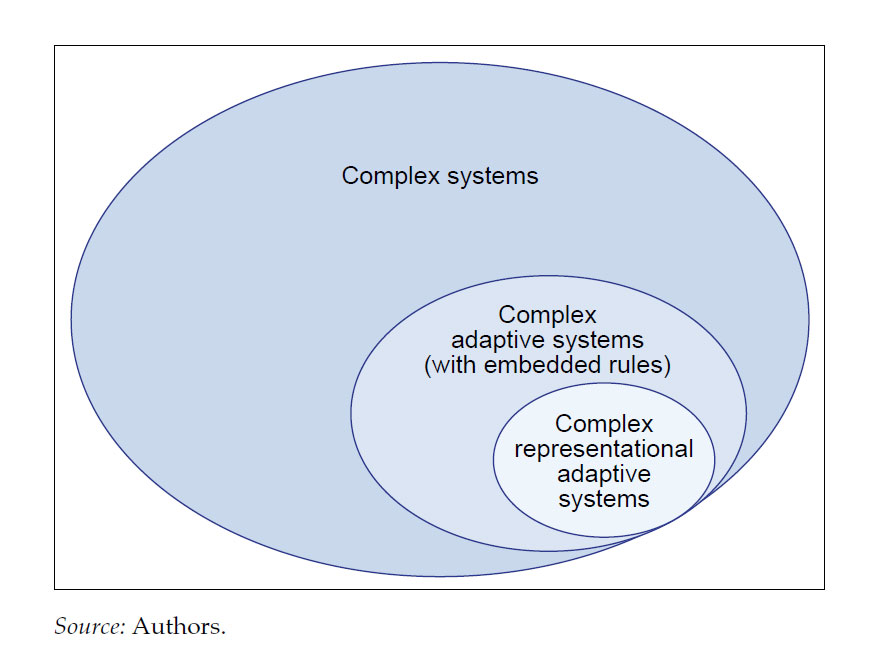

Complex adaptive systems have all the features of complex systems, such as additive and multiplicative causation, positive and negative feedbacks, and disproportional causation or non-linearity. In addition, they survive, reproduce and evolve; enabled by embedded rules or “schemas” — representations of their external environments that guide action in that environment in response to selection pressures (Gell-Man 1995). DNA can be considered a type of schema, as are instinctive or autonomic behaviours built into the neural networks of organisms. As these rule sets are subject to random mutation, systems whose schemas are more adaptive to their environment will be more likely to survive and perpetuate, along with the schemas themselves. The presence of such schemas, and the adaptive nature of the system, could be understood as the simplest, most irreducible test for defining life.

In human societies, shared concepts such as ideologies and identities can be understood as the internal schemas of complex adaptive systems. However, we propose that these belong to a further subset of complex systems: the complex representational adaptive systems. Such systems have all of the features of complex adaptive systems, allowing us to apply the tools of evolutionary and complexity theory to their behaviour. But their schemas are products of abstract representational thought, necessitating the application of cognitive science understandings of mind and intelligence. If complex adaptive systems constitute life, then complex representational adaptive systems constitute human life, and all systems of which human life is a necessary part.

Four concepts drawn from complexity science have proven useful for understanding ideologies as complex representational adaptive systems. The first two — networks and state space — provide ways of conceptualizing the domain in which ideological systems form and operate. The next two — attractors and threshold change — describe processes that contribute to shaping ideologies.

- Networks: Ideologies can be understood as the emergent products of multi-level interactions between the neural and conceptual networks that make up individual minds and the networks of social communication that constitute political communities. We can apply analytical tools developed by network science, a subfield of complexity science, to both kinds of networks. Such a multi-level systems approach to ideology offers a means to simultaneously account for factors usually examined in isolation, from genetics and neuroscience to cognitive psychology and social history.

- State Space: Ideologies must necessarily — whether explicitly or implicitly — take positions on certain basic questions relevant to political or economic order; for example, the relative importance of the future versus the past or the degree to which individuals can choose their fate. Therefore, it should be possible to classify ideologies in relation to one another within a hypothetical space defined by the dimensions according to which of their positions on such questions might differ. Such an approach offers greater explanatory depth than existing bipolar (left-right), two-factor or multi-factor schemes for classifying ideologies, offering as well a means to understand how particular social environments generate particular ideological groups and introduce constraints to ideological change.

- Attractors: Not all locations within the state space are equally probable, as not all possible combinations of answers to the questions are equally coherent. Within a given social or cultural context, certain combinations of values will prove more coherent than others, and it is at these points that groups tend to cluster around shared belief-systems. These constitute attractors; discrete points of equilibrium where ideological groups are likely to form.

- Threshold Change: When an ideology changes, it moves through the state space. If the state space has attractors, then this change — whatever its cause — is unlikely to be gradual and incremental. Rather, it will appear rapid and dramatic, similar to a gestalt shift or flip between psychological states, as multiple individuals transition from one attractor within the state space to another in a manner that presents as mass-conversion. Methods used to model critical transitions or “tipping points” can be useful for demystifying this phenomenon.

A synthesis of cognitive science, with its rich theories of mental representation, and complexity science, with its understanding of the structure and dynamics of large multi-level, multi-element systems, offers great potential to advance our understanding of ideology and its role in conflict.

To continue reading please access the full paper from our Digital Library here.

Notes[1] We cannot rigorously document that he made this observation, but Lucie Edwards, in her capacity as Canada’s High Commissioner to South Africa (1999–2003), heard him use this metaphor on a few occasions.

[2] The Zapatista Army of National Liberation is a leftist, mostly indigenous group involved in armed insurgency in the 1990s with whom the government has since been able to come to at least an uneasy modus vivendi.

[3] For further elaboration on the existing literature on ideology, we recommend two works by members of the ICP research team: Leader Maynard (2013) and Mildenberger (2013).