Professional Military Education as an Hegemonic Tool in US International Security Policy

14 Jan 2016

By Duraid Jalili for Strife

This article was external pageoriginally publishedcall_made in Special Issue I (2015) of Strife Journal.

‘Humble’ Beginnings

In 1949 the U.S. began training foreign military personnel as part of the “Military Assistance Program” authorized by Congress. Initially designed to help rebuild European forces (alongside Foreign Military Sales) as a barrier to Soviet influence, the U.S. perspective on the value of trans-national military education was underpinned by a division between the known value of such activities, and the nature of a closed-organisational model.

As shown in U.K. Cabinet Office archives, for example, on 27 November 1945 Field Marshal Henry Maitland Wilson, Chief of the British Joint Staff in Washington D.C. sent a confidential telegram to the U.K. Chiefs of Staff. His message was regarding an offer which had been made to the U.S. Chiefs of Staff to send U.S. officers to attend the U.K.’s Imperial Defence College (now known as the Royal College of Defence Studies). In the letter, Wilson outlined a personal conversation held with General George C. Marshall the U.S. Army Chief of Staff in which Marshall stated that: ‘...the U.S. Chiefs of Staff would be glad to reciprocate. However, [they] were concerned to keep the whole thing as quiet and informal as possible on the grounds that if it got about they would be inundated with requests to accept students at American colleges from all the Latin American countries.’1

Just under five years later on 7 September 1950 (and only one year after the commencement of the U.S.’s Military Assistance Programme), a U.K. Chiefs of Staff Committee meeting regarding the proposed creation of the NATO Defence College, noted that ‘the idea of setting up such a College has been conceived by the Americans as an alternative to acceding to a French request for vacancies at the U.S. National War College and Industrial College of the Armed Forces, and at the British Imperial Defence College.’2

Despite this initial reluctance, over the next sixty years the U.S. engaged in an exponential expansion of external foreign military training, as well as significantly widening its capacity to incorporate and integrate foreign military and civilian students within its own national training courses. In 1976, for example, it created its benchmark International Military Education and Training (IMET) programme, designed to centralise a wide range of leadership and management training for both current and (potential) future military leaders.

Such programmes were not devoid of criticism or controversy. In the 1994 documentary film ‘School of Assassins’ for example, Robert Richter chronicled the wide range of human rights abuses committed by graduates of the U.S. Army School of the Americas (SOA).3 Such criticisms over questionable human rights records, combined with Congressional in- fighting regarding the value of such programmes, led U.S. Congress to deny foreign training assistance to several countries over the years, impacting both upon individual foreign students and wider political and diplomatic relations between countries.4

Yet, despite these setbacks, total U.S. Government expenditure on foreign military training continued to increase as a part of the U.S.’s international security policy. Taking the most recent figures available, for example, over the period of 2003 to 2013 inclusive the U.S. Department of State and Department of Defence spent a combined $6,013,484,553 on foreign military training programmes, averaging 0.09% of total U.S. defence expenditure across the period. During this 11 year period alone annual PME expenditure rose alongside wider defence expenditure by over 50%, from a total of $490,537,172 in 2003 to a total of $738,321,586 in 2013.5

This essay will consider how this expenditure can be used to assess both the sustained contemporary emphasis on the value of ‘soft power’ within U.S. defence and security strategies, and the tactical implementation of such strategies on both a regional and national level.

Scholarship and Soft Power

Since its introduction by Joseph S. Nye in 1990,6 the concept of soft power has gained significant traction in both governmental and non-governmental strategic thought, with ‘visible impact on American foreign policy as well as that of other countries’7. As defined by Nye, the concept centres around the ‘ability to get what you want through attraction rather than coercion, or payments’, which itself ‘arises from the attractiveness of a country’s culture, political ideals, and policies.’8

If I am persuaded to go along with your purposes without any explicit threat or exchange taking place - in short, if my behavior is determined by an observable but intangible attraction - soft power is at work. Soft power uses a different type of currency - not force, not money - to engender cooperation - an attraction to shared values and the justness and duty of contributing to the achievement of those values. […] Co-optive power - the ability to shape what others want - can rest on the attractiveness of one’s culture and values or the ability to manipulate the agenda of political choices in a manner that makes others fail to express some preferences because they seem to be too unrealistic.9

Within this framework, education provides a significant means of facilitating this power. In outlining this, Nye quotes a 2001 statement by then Secretary of State Colin Powell, in which he promotes the U.S. State Department’s Fulbright Scholarship programme with the assessment that ‘I can think of no more valuable asset to our country than the friendship of future world leaders who have been educated here.’10 For Nye, the value of such an asset is self-evident, in that many ‘of these former students eventually wind up in positions where they can affect policy outcomes that are important to Americans.’11 Indeed, as stated by Eric D. Newsom, former U.S. Assistant Secretary of State for Political- Military Affairs:

I believe, for the most part, we do not fully appreciate how IMET and similar programs impart American values to the recipients in foreign militaries, both directly and indirectly. The stability we saw in military forces around the world during [the] recent radical decrease in defence budgets would have resulted in coups which today never materialized, in part because of the learned respect for civilian control of the military.12

Although it is difficult to quantitatively define the extent to which the policies and actions of foreign governments and militaries have been influenced by foreign military education, it is possible to gain significant qualitative data on individual cases. In John A. Cope’s 1995 study of the IMET programme, for example, we find evidence that foreign PME and shared educational experiences: enabled greater U.S. cooperation with Middle Eastern officers during the Persian Gulf War ‘because most of the high ranking [officers] had attended military training in the U.S. and understood how to work with us’13; reduced ‘emotional and uninformed reactions [...] against the U.S.’ by Brazilian military officials14; and even ‘produced at least two unauthorized channels of communication between senior Argentine and U.S. officer-classmates’ during the Malvinas/Falklands War in 198215. Perhaps the most interesting encapsulation of this, however, is found in the 1993 Congressional testimony of Lieutenant General (Ret) William E. Odom, former Director of the U.S. National Security Agency:

Another kind of desirable influence through IMET is demonstrated by US- Pakistani relations immediately after the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan. General Zia, the President of Pakistan, was being urged by his foreign minister to scorn US offers of assistance in favor of coming to term with Moscow. Because Zia had attended two US Army schools, and because he had made extremely close friends with ordinary American citizens during those two years, he was subjectively inclined toward the US offer. As a party to the meeting with him in Pakistan when he made the decision to accept the US offer, tying his policy to US strategy for Afghanistan, I gained the impression that his IMET experience was a critical factor in his decision.16

Indeed, both before and after Nye’s original definition of ‘soft power’ in 1990, it is this effort to influence both individual decisions and wider critical thinking of foreign military and civilian leaders which has defined and incentivised governmental and military expenditure on foreign military training. As reinforced by Cope’s analysis of the IMET programme:

As U.S. foreign aid continues to collapse under strong congressional pressure to economize, this “bonsai” appropriation in the vast forest of security assistance programs has gained in standing, potency and importance to national security far surpassing that envisioned by its political framers in 1976.17

Through these efforts, the U.S. has sought to counteract the critical belief that ‘soft power, and particularly culture as soft power, is often something over which governments have little control but with which they must reckon.’18 Indeed, in recent years this focus has been further enhanced by a new tactical emphasis on areas such as influence operations which (as defined by the U.S. Army Leadership Centre) engage with ‘planning and enacting behaviors that are intended to alter another’s beliefs, attitudes, and/or actions’ across ‘intergovernmental groups, other militaries, [...] and others that fall outside the traditional chain of command’19.

The Who, the What, the Why, the When and the Where?

If foreign military training can be used to create influence, therefore, then who should be influenced, in what ways, to what ends, at what times, and in what countries? Practically speaking, the means of engagement can be divided into two categories: ‘education’ and ‘training’. Education refers to courses whereby foreign officials are taught strategic and tactical aspects of contemporary defence and security. The goal of such teaching is to provide current and future leaders with the analytical skills and knowledge to enable them to engage at the highest levels of operational, policy and strategy roles. In doing so, governments create a network of future international leaders, with potential sympathy to U.S. culture and strategic interests, as well as a means of conceptualising political and military problems based on ‘U.S.’ best practice.

Although such education occurs at the Staff Colleges for mid-career officers, at its most senior level it is specifically designed to target an elite of military and civil service officials, who have been hand-chosen by their representative governments as potential future leaders. In the U.S. such ‘fourth-tier’ education takes place at one of six colleges: the U.S. National War College, the Dwight D. Eisenhower School for National Security and Resource Strategy and, at the service level, at the U.S. Army, Air, Naval and Marine Corps War Colleges respectively.

The emphasis on influential trans-national connections that occurs within these colleges is encapsulated perfectly in Judith Hicks Stiehm’s overview of the U.S. Army War College induction process for new students, which involves a presentation graphic with pictures of graduates who went on to become ‘strategic leaders’. After photos of six U.S. Commanders in Chief and seven senior U.S. Generals, the presentation then features four international graduates, ‘including one from the Czech Republic, who is quoted as having learned at the USAWC the importance of “civilian supremacy over the military” and of having the skills that let one exercise “leadership of the armed forces in the democratic spirit.”’20

Complementing this higher-level of engagement, the process of ‘training’ centres around the provision of practical and technical assistance to soldiers and officers engaged in role-specific activities. Examples of such training range from counter insurgency, drug interdiction, peace-keeping and counter piracy operations, to de-mining, firearms training and mechanical engineering courses. In principle, the overarching goal of ‘training’ versus education is to ensure that the practical and technical aspects which underpin the military function occur in the most proficient possible manner, both in and out of theatre. In comparison to education, this ‘training’ process provides the main complement to foreign military sales, as well as acting as a potential force multiplier for the U.S. military (ie. creating a network of foreign troops trained to U.S. standards, who can therefore be relied upon to engage in regional conflicts which the U.S. may wish to engage in by-proxy or as part of a coalition operation).

Underlying this two-part structure of influence, is a vast substructure of subject-, rank- and regional-specific programmes run separately and jointly by the U.S. Department of Defence and U.S. Department of State. These include Department of State funded programmes such as the African Contingency Operations Training and Assistance (ACOTA); Global Peace Operations Initiative (GPOI); International Military Education and Training (IMET); and International Narcotics and Law Enforcement (INL) programmes. Department of Defence specific programmes include Combatant Command Security Cooperation Activities; Regional Defence Combating Terrorism Fellowship Program (CTFP); Section 1004 Drug Interdiction and Counter-Drug Training Support (CDTS); Section 1206 (‘Global Train and Equip’); the Service Academy Foreign Student Program; the Aviation Leadership Program; and Professional Military Education (PME) exchanges. In addition to these direct programmes there exist a range of regional programs with Department of Defence funding, such as the Asia-Pacific Center for Security Studies (APCSS), the George C. Marshall European Center for Security Studies (Marshall Center), the Center for Hemispheric Defence Studies (CHDS), the Near East South Asia Center for Strategic Studies (NESA Center), and the Africa Center for Strategic Studies (ACSS).

Although, as previously mentioned, it may be impossible to quantify the impact of this influence, it can be argued at the very least that this range of programmes allows the U.S. government to: increase military-to-military and military-to-government influence (especially by identifying and training future national leaders); promote self-sufficiency in partner nations (eg. in technical, economic, judicial, socio-political, and military areas); expand foreign understanding of and subscription to U.S. culture and values; encourage adherence to democratic thinking and human rights concepts in foreign militaries; prepare for and pre-empt emerging security concerns; enhance operational capabilities in a by-proxy or coalition military capacity within conflict hotspots; participate in international narcotics control; facilitate economic ties through foreign military sales; and normalise U.S. standard operating procedures, as well as wider strategic and tactical doctrine, as a global standard for military forces.

As has been shown, therefore, by analysing U.S. foreign military education programmes it is possible to achieve a greater understanding of how the U.S. Government and its Armed Forces conceive of notions of ‘influence’ and ‘soft power’, as well as contextualising PME as a means of creating strategic and tactical gains in the global socio-economic and politico- military spheres.

In addition to this, however, investment in foreign military education programmes provides an interesting framework by which to analyse the implementation of U.S. strategic aims on both a regional and national level. If we take into account, for example, the overall spending trends on foreign PME across both Department of State and Department of Defence agencies, it is possible to see clear regional trends.

In assessing such figures, we find a microcosm of the U.S.’s wider strategic aims21. The Near East region, for example, shows a spending climate significantly informed by energy interests in the Gulf, and military engagement in Iraq and Yemen. Interestingly, however, the dip and rise in spending across the period cannot simply be attributed to the start and end of U.S. engagement in Iraq. In fact, training expenditure in Iraq seems almost a process of homeostasis rather than forward planning, with major investments occurring mostly on a triennial basis. Instead, we find the figures influenced by a significant reduction in training investment in Egypt (-49%), the U.A.E. (-65%) and Israel (-70%) respectively. In comparison, the notable increase in investment towards the end of the period is heavily influenced by the steady increase in expenditure across the period in Yemen (313%), Oman (419%), Saudi Arabia (522%), Lebanon (2,902%), and a rapid increase in funds for Libya (3,473%) between 2007-2014.

In the African region, the significant increase in investment can be broadly attributed to counter-terrorism and maritime piracy concerns, as well as wider peace-keeping engagement, and securing of future trade and energy links. Yet, interestingly, a significant proportion of this rise in investment is directly linked to a focussed increase in training funds for six countries: Cote D’Ivoire (1,170%), Burkina Faso (1,571%), Niger (2,248%), Somalia (3,377%), Uganda (4,940%), and Burundi (7,450%). As seen in Table V, this reveals a trend of counter-terrorism investment which not only focuses on individual cases, but also results in a geo-strategic barrier between Boko Haram in West Africa and Al Qaida in North West Africa.

Increased investment in the East Asia & Pacific region bears clear linkage to wider U.S.-Chinese strategic manoeuvring. Of specific interest is the increase in investment in Cambodia (932%) and Vietnam (1,185%), as well as the status of Singapore as the country with the highest level of investment across the entire 2003-2013 range, with a total expenditure of $830,366,014 (surpassing Saudi Arabia, in second place, by nearly $300million). In South Central Asia, there is a predictable concentration of PME investment in Afghanistan, Pakistan and India (which, when combined, constitute over 74% of expenditure within the region). Yet, despite this, we find a broadly similar ratio of investment growth in Kyrgyzstan (179%), the Maldives (360%), and Tajikistan (436%), as we do in Pakistan (114%), Afghanistan (229%), and India (796%).

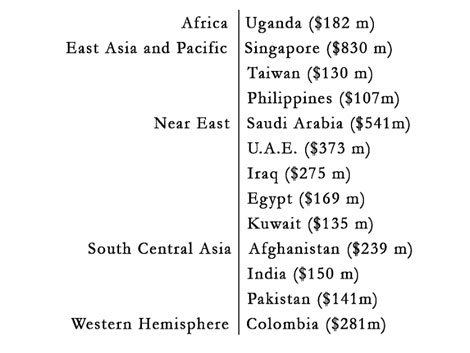

At the top end of the spectrum, there are 13 countries in whom the U.S. has invested over $100 million across the 2003-2013 period:

Although a total of $6billion has been spent across 178 countries and protectorates across the 2003-2013 period, over 59% of that total expenditure is concentrated across these 13 countries. This spectrum suggests that, despite the potential for small-scale tactical manoeuvring through PME investment, the brunt of U.S. foreign training investment is based on a strategy of focussed engagement with key countries, who can be defined within one or more categories: current conflict environment, rich in natural resources, tactically advantageous in terms of geography, and potential exporter of drugs or terror threats to the U.S.

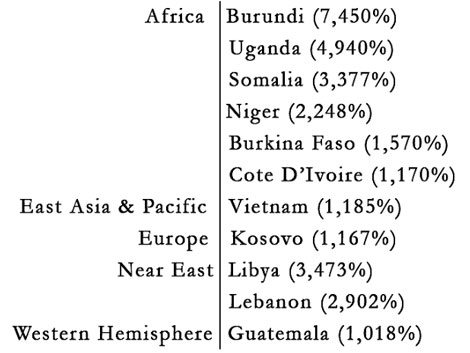

As a means of contrast, however, only one of these nations features on the list of 11 countries for whom the U.S. has increased PME investment by over 1000% across the same period:

This contrast supports the data previously shown in Table IV, revealing that although the U.S. does use PME to maintain key strategic partners within each continent, it remains engaged in a shifting regional focus with significant emphasis on both counter-terrorism specific and wider politico-economic engagement within Africa.

Based, therefore, on the spectrum of contexts and statistics available for foreign PME investment, and wider strategic trends, it is possible to draw a broad range of general conclusions and potential theories for the future of U.S. hegemonic aims. Perhaps most obviously, it is evident that the U.S. will continue to engage in a wide spread of foreign military training activities across Latin America, Africa, the Near East, East Asia & Pacific, and South Central Asia. Central to this will be a focus on ‘key’ nations with whom the U.S. has long-term pre-existing links, based on energy resources, tactical geographical placement, or their potential for fostering and exporting terrorism and/or narcotics.

As part of this, it seems likely that there will remain stable investment in Latin America, with the potential for gradual reductions in counter- narcotics spending as individual U.S. states slowly legislate towards de-criminalisation. Investment in Africa will likely continue to increase at a higher rate than other regions, both in line with continuing issues regarding political instability, counter terrorism, and maritime security, and as part of a wider mission to counteract increasing Chinese socio- economic influence and foreign military sales prospecting with regional trade allies.

In comparison, it appear probable that there will be a continued decrease in investment within Europe, with a geographical movement towards increased training in North- and South-East Europe (both due to fear of Russian expansionism and the ambiguous status of Turkey as a regional influencer). Linked to this, as well as natural energy resource requirements, it is possible that there will be a dual increase in both education and training for a certain selection of the ‘-stans’ in Central Asia (yet this may be more gradual due to their comparative strength as regional powers, and comparative lack of current internal conflict).

On the wider level, it is feasible that, either in a concerted government-wide effort, or due to individual actors within specific training programmes and colleges, there will be an increasing tendency towards generating new methodologies to cultivate and exert influence through alumni and other ‘non-formalised’ student networks. In addition, there may be a movement towards increased regularity of U.S. educational engagement with foreign officers throughout their career, achieved through short, in-country or distance learning refresher courses, in order to maintain and enhance personal ‘affinity’ with U.S. culture and strategic priorities through frequency of access. What is certain above all, however, is that the use of foreign military education as an hegemonic tool will remain a valuable asset in U.S. strategic policy.

Footnotes

1 National Archives, UK. CAB 120/8. Secret Cypher Telegram, received by O.T.P. From J.S.M., Washington to Cabinet Officers. FMW 214. 27 November, 1945.

2 National Archives, UK. DEFE 6/13. Section 89. Previous Reference: J.P. (50) 88 (O). COS (50 97th Meeting, Minute 3.

3 School of the Americas Assassins. Dir. Robert Richter. Richter Productions, 1994.

4 M.A. Pomper, ‘Battle Lines Keep Shifting Over Foreign Military Training’, Congressional Quarterly Weekly (29 January 2000), pp. 193-196.

5 All data on PME investment used within this study is taken from the annual ‘Foreign Military Training’ report to U.S. Congress, compiled by the U.S. Department of Defense and Department of State. Available at http://www.state.gov/t/pm/rls/rpt/fmtrpt/ (Last accessed on 16 February 2015)

6 J.S. Nye, Jr., Bound to Lead: The Changing Nature of American Power (Basic Books, 1990).

7 K. Ifantis, ‘Soft Power: overcoming the limits of a concept’, in McKercher, B.J.C. Routledge Handbook of Diplomacy and Statecraft (Routledge, 2012), p. 441.

8 J.S. Nye, Jr., Soft Power: The Means to Success in World Politics (PublicAffairs, 2004).

9 Ibid, p. 7.

10 Ibid, p. 44. Original quotation by C. Powell, ‘Statement on International Education Week 2001’. Available at http://2001- 2009.state.gov/secretary/former/powell/remarks/2001/ 4462.htm. (Last accessed on 31 October 2014)

11 Ibid, p. 45.

12 Quoted in Pomper, p. 196.

13 Response to Institute for National Strategic Studies (INSS) Research Survey, Fort Bragg, NC. 27 January 1995. See J.A. Cope, International Military Education and Training: An Assessment. A report for the Institute for National Strategic Studies, at the National Defense University (Diane Publishing, 1995), p. 30.

14 Response to INSS Research Survey, Washington, DC. 30 January 1995. See Cope, p.27.

15 Response to INSS Research Survey, Miami, FL. 3 February 1995. See Cope, p. 28.

16 LtGen (Ret) W.E. Odom, ‘US Military Assistance After the Cold War’, Testimony before the Senate Foreign Relations Sub-Committee on International Economic Policy, Trade, Oceans and Environment. 16 June 1993.

17 Cope, p. 1.

18 Ifantis, p. 433.

19 R. Mulvaney et al., ‘A Grounded Model of Leadership Influence Techniques’, Conference Presentation at the Annual Meeting of the International Military Testing Association. Lucerne: Sept/Oct, 2010. IMTA. Available at external pagehttp://www.imta.info/pastconferences/Presentations.aspx?Show=2010call_made (Last accessed on 10 October 2014).

20 J.H. Stiehm, The U.S. Army War College: Military Education in a Democracy (Temple University Press, 2002), p. 58.

21 It should be noted that PME as a complement to Foreign Military Sales plays a significant role in the figures shown. Although it could be argued that this factor places an anomalous link between U.S. soft power aims and countries with enough finances (and relevant offset programmes) to invest in U.S. technology, it can equally be argued that such investment by these countries is a key indicator of their preference towards U.S. influence versus that of its competitors. Thus, although the data provides a valuable perspective, a larger analysis in which this data is correlated with the respective GDP and defence investment data of each country has the potential to provide alternative results.

.jpg)