Is Britain Back? The 2015 UK Defense Review

15 Feb 2016

By Daniel Keohane for Center for Security Studies (CSS)

This article was originally published by the Center for Security Studies (CSS) on 5 February 2016.

The government of the United Kingdom (UK) published a new security and defense review in late November 2015, amid ongoing renegotiations with the EU over Britain’s terms of membership and a debate on joining the bombing campaign against the so-called “Islamic State” (IS) in Syria (it had already done so in Iraq) following terrorist attacks in Paris the same month. The document combines a national security strategy with a strategic defense and security review (SDSR).

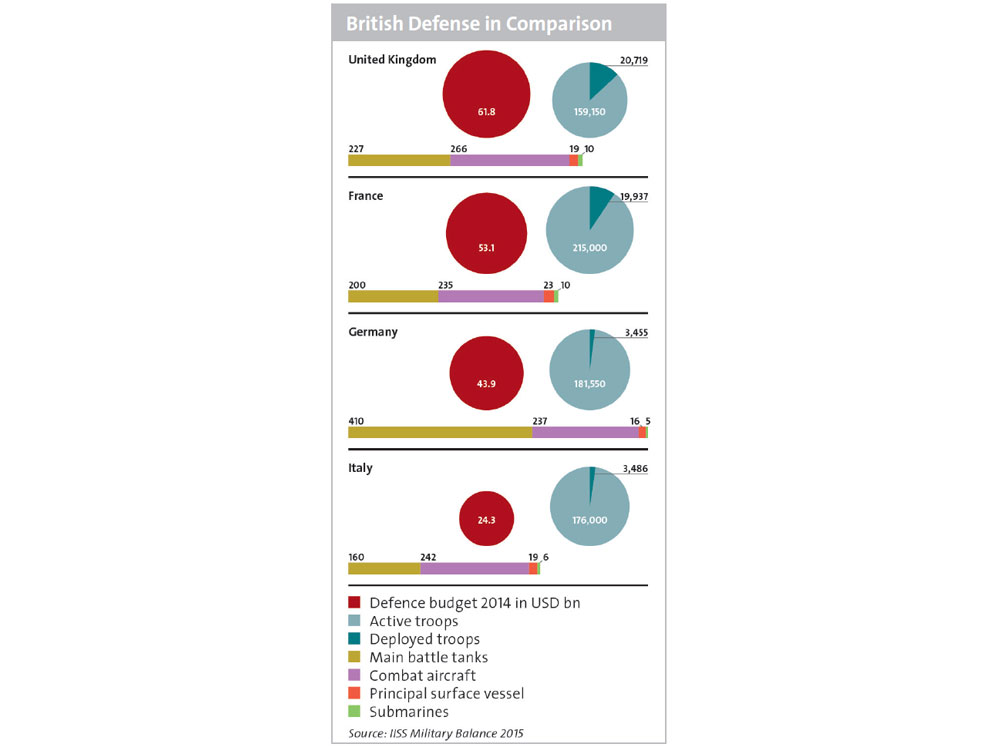

In recent years, some NATO allies and international security experts have criticized the UK for not contributing as much as it could to tackling the growing number of crises in and around Europe. Having long been considered Europe’s leading military power (alongside France), the image of the UK as a declining military power had taken hold in some expert and political circles, both domestically and internationally. In many respects, the new UK defense review is a response to these criticisms.

The Defense Review in Context

Following the May 2010 British general election, a coalition government was formed for the first time since World War II. Amongst many other things, the then Conservative-Liberal government introduced legislation to fix parliamentary terms for five years, and to carry out a review of British security and defense policies – the first full strategic defense review since 1998, following a defense white paper in 2003. They also committed the next British government to carry out another defense review following the 2015 general election (the Conservatives won a parliamentary majority in the May 2015 election).

The 2010 review was inspired more by fiscal austerity than by strategic concerns: the financial crash, and the ensuing economic crisis, had caused the government budget deficit to more than quadruple between 2007 and 2009 (from £ 36 billion to £ 156 billion, according to the UK Office for National Statistics). The defense budget was slashed by around eight per cent in the five years after 2010, and the army was reduced to its lowest manpower level since the Napoleonic era.

Some existing capabilities were decommissioned with immediate effect, such as the flagship HMS Ark Royal aircraft carrier, and some planned projects were cancelled, such as new Nimrod MRA4 maritime patrol aircraft. Other projects were delayed, including two new aircraft carriers (meaning the UK would not have carrier strike capability for a decade), or their acquisition orders were modified, for instance by switching from the Short-Takeoff-Vertical-Landing (STOVL) model to the cheaper conventional carrier version of next-generation F-35 fighter jets (this decision was reversed in 2012).

Because of the urgent focus on cost cutting, and a relatively rushed deliberation process, the November 2010 review had a cobbled-together feel and lacked strategic coherence. For example, it considered a large-scale military attack by other states to be a “low probability”, with terrorism and cybersecurity identified as strategic priorities. Nevertheless, acquiring two new aircraft carriers was classified as a priority capability investment, even though their role in tackling cybercrime or terrorism was not immediately obvious.

At that time, the UK was still heavily involved in the international counterinsurgency effort in Afghanistan, having removed combat troops from Iraq in 2009 (some trainers remained until 2011). These long-term external operations had taken up the majority of British defense resources for almost a decade. Because of mixed results in both Afghanistan and Iraq, and the urgency of the domestic economic crisis, in 2010 the British public was weary and starting to become increasingly wary of international military operations. For example, although he had co-led the 2011 NATO intervention in Libya, in 2013, Prime Minister David Cameron lost a parliamentary vote to bomb the forces of Syria’s Bashir al-Assad following their suspected use of chemical weapons.

However, between 2010 and 2015, a number of new strategic and operational challenges exposed some gaps in the approach contained in the 2010 SDSR. The NATO intervention in Libya in 2011, which the UK led with France, showed the usefulness of having carrier groups and exposed a shortage of precision munitions as well as some intelligence-gathering, surveillance, and reconnaissance equipment. The Russian annexation of Crimea in 2014, and subsequent incursions into NATO airspace and waters not only showed that state-based threats also needed to be deterred, but also exposed a lack of maritime patrol aircraft.

A Fuller-spectrum Strategic Approach

The 2015 SDSR is more coherent and ambitious than its predecessor. Because of intervening Russian aggression in Ukraine (alongside other crises and the rise of the IS) since 2010, it calls for the UK now to simultaneously tackle non-state challenges and deter state-based threats. For cross-border challenges, there is some continuity with 2010, as the 2015 document continues to highlight the threats from terrorism, cybercrime, and serious and organized crime. Notably, the UK will double the funds allocated to cybersecurity to £ 1.9 billion over the next five years. In addition, a new national cybersecurity strategy and program will be developed during 2016.

Despite the urgent security crises in Europe’s immediate neighborhood (Libya, Syria, Ukraine), the 2015 review emphasizes – like the 2010 version – that the UK should keep a global outlook. The usefulness and breadth of the country’s diplomatic network and development program (the UK is the first G7 country to spend 0.7 per cent of gross national income on development assistance) are spelled out in the 2015 review, more coherently than in 2010, as examples of the UK’s global influence and ways of building stability to complement other security efforts, including the use of military means.

Moreover, a desire to work more closely on security issues with African, Middle Eastern (like Bahrain), and Asia-Pacific partners (such as Australia and Japan) is spelled out more forthrightly than before. The UK intends to invest much more in “defense engagement”, and will establish defense staffs for training and capacity-building with partners in the Gulf, the Asia-Pacific region, and Africa during 2016.

Alliances are also heavily underlined in the 2015 review, with a strong emphasis on working through NATO, which the UK considers to be the “bedrock of our national defense”. The UK intends to remain “NATO’s strongest military power in Europe” and will continue to contribute to the Atlantic alliance’s defensive efforts in Eastern Europe, such as Baltic air policing and military exercises. In addition, the UK intends to deepen its bilateral cooperation with three key allies in particular: the US, France, and Germany.

These sections covering NATO and bilateral cooperation with key allies are followed by a section on security cooperation through the EU. The document states that the EU has “a range of capabilities to build security and respond to threats, which can be complementary to those of NATO”. Those capabilities include EU missions, both military and civilian, alongside development and security support. The UK would also like the EU and NATO to work together more effectively in tackling security challenges, such as countering hybrid threats.

Regarding military tasks, the 2015 review highlights two aspects in particular. One is the ongoing need for strong deterrence capabilities, represented by the continuation of the Trident nuclear program. Another aspect is the ability to respond quickly and robustly to a variety of international security crises, i.e., to deploy strike capabilities overseas rapidly, ranging from special forces to aircraft carrier groups. Longer-term counter-insurgency deployments of the type that had characterized British military operations in Afghanistan and elsewhere during the 2000s are no longer viewed as an operational priority. Instead, the main operational priority will be the capability of projecting military power globally quickly and robustly, alongside a greater emphasis on deterrence.

Spending and Capabilities

This fuller-spectrum strategic approach will need resources, and among the military establishment, there had been fears before the review that the UK would continue to cut its defense budget. This was because following the May 2015 general election, the Chancellor of the Exchequer, George Osborne, made clear that he wished to continue with deficit-cutting policies. However, to the surprise of some, London intends to increase defense expenditure by around five per cent by 2020, and promises to meet the NATO target of spending at least two per cent of GDP on defense each year over the same period.

Meeting NATO’s 2 per cent target is important for two reasons. First, the target was agreed at a 2014 NATO summit hosted by the UK (in Wales), implying that Britain should try to set an example to other NATO allies. Second, according to NATO estimates, only three other European members – Estonia, Greece, and Poland – met this target in 2015, so London is and intends to remain in the vanguard of European defense spenders in the coming years. But at least two factors may challenge the ability of the UK to meet the 2 per cent target in real terms over the next five years. This pledge is based on economic forecasts anticipating at least two per cent GDP growth each year to 2020, so any drop below this rate would imply a real reduction (even if not a nominal fall) in the defense budget (bearing in mind that the real price of advanced equipment projects typically rises by around five per cent a year).

Another uncertainty is the economic fallout following a possible British exit from the EU (sometimes referred to as “Brexit”) – the UK government has to hold a referendum on its EU membership by the end of 2017, and is expected to do so during summer or fall of 2016. Estimates vary wildly as to the potential economic consequences of a Brexit, but any resulting drop in GDP would impact real defense spending. For example, a 2015 study by two respected German research institutes, the Bertelsmann Stiftung and the ifo Institute, calculated that a worst-case scenario Brexit could knock some 14 per cent off the UK’s GDP, costing the economy more than € 300 billion.

More specifically, London intends to invest £ 178 billion (€ 236 billion) in military equipment over the coming decade, an increase of £ 12 billion (€ 16 billion) over previous plans. That money will be spent both on preplanned projects, such as maintaining the Trident nuclear deterrent and developing two new aircraft carriers, and on closing some capability gaps that resulted from the austerity-driven 2010 review. For example, the air force will acquire nine new maritime patrol aircraft to monitor Russian submarine incursions, together with fielding 24 stealthy F-35 fighter jets on the two new aircraft carriers within a total of 42 aircraft by 2023 (the UK remains committed to buying 138 F-35s overall).

The navy will receive new combat ships, but only eight new Type 26 frigates are guaranteed – admirals had hoped for 13 – with perhaps around five smaller and cheaper vessels filling the gap. Some British maritime experts are concerned that the UK will not have an adequate number of surface combatants to perform an increasing number of missions in the coming years. The overall externally deployable strength of the combined British armed forces will increase from 30,000 in the 2010 review to 50,000 by 2025. Roughly 40,000 of these troops will come from the army. More specifically, the army will be able to deploy at very short notice two 5,000-strong “strike brigades” equipped with new Ajax armored vehicles. Moreover, almost 2,000 additional intelligence officers will be recruited by MI5 and MI6 (the domestic and foreign intelligence services) and GCHQ (the signal-intelligence agency) to track terrorists and cyberthreats.

(click to enlarge)

Reactions and Prospects

Overall, reactions to the new review have been moderately positive in the UK defense establishment, in large part because of the promise to stop the decline in defense spending. As one analysis from the Royal United Services Institute described it: “Over the last five years, the UK has been increasingly seen by its allies […] as a power in retreat. This SDSR […] should help reverse this perception”. However, another analyst from Chatham House worried that this review contained hidden problems for the future, and was driven more by inter-service political lobbying than by the need to match appropriate means with what should be strategic priorities.

Furthermore, the new leadership of the main opposition party, Labour, has raised questions about the increasing cost and utility of the Trident nuclear deterrent, ahead of an expected parliamentary vote during 2016 to continue with the program (known as the “main gate” decision). The estimated cost of replacing the submarines carrying Trident missiles has risen from £ 25 billion (in the 2010 defense review) to £ 31 billion over the next decade.

The UK’s renewed level of military ambition is important for NATO, as the UK is the largest European defense spender in the Atlantic alliance. Following recent grumbling by some NATO allies, especially the US, about London’s declining military willingness and capability, the main political message of the new defense review is that Britain is back as a serious military power. Whether this proves to be the case in practice remains to be seen, as unforeseen events may expose glaring capability gaps or budgetary difficulties may hamper some equipment projects. But the intention is clear.

Within the European context, it will be interesting to compare the British document with two other ongoing review processes that will conclude later in 2016: the German defense white book and the EU global strategy, which will set out priorities for EU foreign, security, and defense policies. It is unlikely that those two documents will aim for similar levels of military ambition as the British review.

Even so, as mentioned above, the UK review underlines the value of cooperating closely with European allies, including through the EU as well as NATO, highlighting France and Germany in particular. This is sensible, not only because European cooperation is vital for managing the myriad of cross-border security challenges the UK faces in and around Europe, but also to bolster the UK’s international influence. A pre-review UK defense ministry study, entitled “Future Operating Environment 2035”, noted that London’s global clout could decline within 20 years due to the growing number of influential powers such as Brazil, China, and India.

The 2015 UK defense review is an ambitious defense plan by European standards, but the threat of a British exit from the EU hangs over British international ambitions. Opinion polls in the UK currently show supporters and opponents of a Brexit in a dead heat. In the worst-case scenario, the UK outside of the EU would probably remain a significant military power (depending on the economic fallout), and would remain both a member of NATO and a permanent member of the UN Security Council. But a Brexit would severely diminish the UK’s standing as a diplomatic player, since it would lose influence in Europe, no longer having a say over the EU’s socio-economic, security, or foreign policies.

Concomitantly, a Brexit would greatly damage the EU’s already-struggling defense policy and, by extension, its foreign policies. Worse, a Brexit could also further harm the credibility of the whole EU project, coming on top of coping with Eurozone woes, the refugee crisis, terrorist attacks, the rise of nationalist politicians, a revisionist Russia, and Middle Eastern disorder. A more unstable EU is not in the UK’s strategic interest. As the 2015 defense review says, “a secure and prosperous Europe is essential for a secure and prosperous UK”.

Further Reading

Ian Bond, «Cameron’s Security Gamble: Is Brexit a Strategic Risk?», in: CER Insight, 21 December 2015.

Malcolm Chalmers, «Steady as She Goes: The Outcome of the 2015 SDSR», in: RUSI Commentary, 23 November 2015.

Daniel Fiott und James Rogers, «The Strategic Defense and Security Review 2015: ‹Offshore Balancer› and ‹Strategic Raider›?», in: European Geostrategy, 24 November 2015.

James de Waal, «This SDSR Hides Problems for the Future», in: Chatham House Expert Comment, 2 December 2015.

«UK augments military and counter-terrorism capacities» , in: IISS Strategic Comments, 25 November 2015.