Time to Seize the Greek Opportunity

22 Feb 2016

By Matthias Bieri, Zoran Nechev for Center for Security Studies (CSS)

This article was originally published by the Center for Security Studies (CSS)in its Policy Perspectives series (Vol. 4/3, February 2016).

Greece’s crisis is also a chance to improve bilateral relations with the western Balkans. Unique political circumstances have the potential to resolve longstanding issues and stabilize the region. However, the EU’s handling of the migration and economic crises will have a decisive impact on any such prospect.

Key Points

- The EU enlargement perspective is still essential for the stabilization of the western Balkans.

- Greece remains a vital player for EU enlargement in the Balkans, amid being the epicenter of Europe’s debt and refugee crises.

- The current political setup provides a unique chance for progress on longstanding issues, which the EU should take advantage of.

- Treating Greece once again as a partner on migration and economics will help the resolution of outstanding issues in the western Balkans.

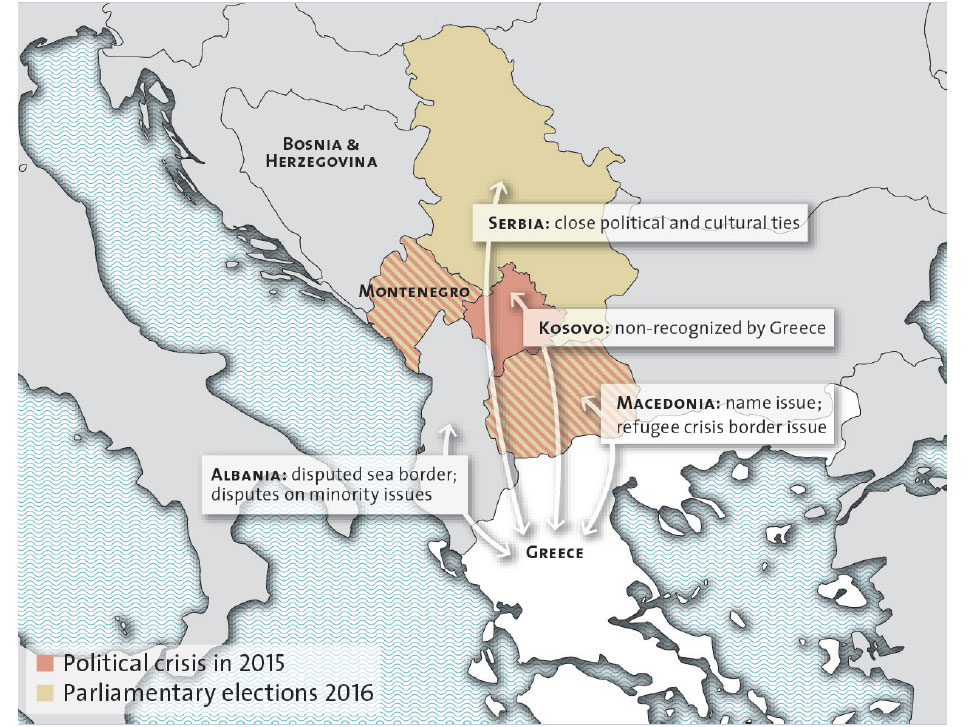

Al though the refugee crisis put a spotlight on the western Balkans, the region still does not get the attention it deserves. Unrest and instability are looming in several countries. Over 20 years of international stabilization through democracy promotion are at risk. One factor hindering the development of the region is that reforms towards strong statehood tend to lose their backing. The EU accession perspective proved to be the telling argument that convinced populations and governments of the need for reform. This perspective has become dimmer as long-standing bilateral issues obstruct the path towards EU accession. Efforts to eliminate these obstacles have had limited success until now. A decisive role in this regard is played by Greece. A strong EU enlargement advocate before the financial crisis, it is still a crucial player in the western Balkans and involved in disputes with Macedonia, Kosovo and Albania. Greek compromises on these issues are a precondition for the EU accession progress of these countries.

Being at the heart of the migration and Eurozone crises, facing nation- wide strikes and controlling just 153 of 300 seats in Parliament, the Greek government’s room for political maneuvering is limited. However, the coming months could offer a set of openings in the region, not least because Syriza is in principal a progressive partner in the western Balkans. Though, for these opportunities to open up, Greece needs to find itself treated again as a European partner.

The EU’s meaning for the western Balkans

Already before the latest crises, “enlargement fatigue” and growing internal challenges led to a loss of interest in EU enlargement. In July 2014, Commission president Jean-Claude Juncker announced an accession freeze until 2020, implying enlargement is not a priority in the near future. For the aspiring western Balkans, however, enlargement remains at the heart of their politics. After years of bloodshed caused by wars and ethnic conflicts, the EU membership perspective offered a vision that helped neutralizing separatist movements, resolving open border issues and bringing economic recovery. It represents the essential incentive for reforms towards a functioning market economy and the establishment of democracy and rule of law. It is in the EU’s core interest that these reforms take place and the western Balkans stand on their own feet. Without a successful reform process, the region will remain dependent on constant European financial support. Once this support vanishes, the region will most certainly be revisited by past troubles.

History has shown that the loss of the EU’s credibility and ground-level engagement lowers both public support and political will for reforms. Growing instability is one very possible consequence. The recent months have shown what this could mean. In Kosovo, the EU has lost much of its credibility due to corruption cases and its co-operation with the unpopular political elite. Political unrest over the EU-brokered normalization deal with Serbia has proven that the country is far from being stable. In Macedonia, the “wiretapping scandal” and the security crisis in Kumanovo in May 2015 causing 22 casualties showed that the former EU model student, gaining EU candidacy status in 2005, is struggling to establish a healthy political environment. This is also due to progress being prevented by the bilateral issue with Greece. Also Albania, Bosnia and Montenegro have recently seen mass protests and massive political dissatisfaction.

Greece’s crucial role in the western Balkans

The role of Greece in the western Balkans is based on proximity and historic ties. Apart from being a determinant in EU enlargement, Greece is economically linked to the western Balkans. The decline of the Greek economy therefore also hit the already economically troubled region. Besides dropping foreign investment and dangers to the regional banking sector, migratory pressure in the countries grew again. For example, in 2007, approximately 600,000 Albanians were working in Greece. Tens of thousands of Albanian workers have had to return home since then, encountering a country without employment opportunities. Their return has cut off the inflow of remittances. The western Balkans would therefore strongly benefit from economic recovery in Greece.

Before the onset of the 2008 financial crisis, forcing Greek politics to focus sharply on internal politics, Greece was an active supporter of the EU enlargement in the western Balkans. Its Europeanisation efforts peaked in 2003 during the Greek EU Presidency. During these six months, Greece set in stone the direction of reforms needed to bring the region closer to the Union. The Thessaloniki agenda reiterated the EU’s unequivocal support for the European course of the western Balkans.

However, Greece’s enthusiasm for the region’s EU integration waned as bilateral issues became stumbling blocks. The dispute with Macedonia over its name, ongoing since 1991, became an ever bigger issue. Greece’s fear of a future Macedonian irredentism and an assumption of the ancient Macedonian heritage – a heritage it considers to be Greek – had major consequences. While the Interim Accord with Macedonia in 1995 nurtured hope for a negotiated solution, Greece in 2008 and in 2009 blocked the further NATO and EU integration process of its neighbor over the issue.

Also in 2008, problems with Kosovo aroused when this country declared its independence. Greece is one of five EU states which do not recognize Kosovo. The reason is twofold: Desire to avoid a precedent for the Cyprus conflict, and alignment with Serbia, a country with which Greece maintains close political, economic and cultural ties. Its non-consolidated position on Kosovo complicates the EU’s Kosovo policymaking.

Grave disagreement also exists with Albania. Albanian advancement in the EU accession process used to be accompanied by Greek pressure to resolve outstanding bilateral issues. The EU-Albania Stabilization and Association Agreement came along with a Greek ultimatum on World War II cemeteries in Albania. Currently, a dispute on the maritime border between the two countries imperils further progress. The ratification of an accord on the issue signed by both states was overturned by Albania’s Constitutional Court. Greece threatens to block the opening of accession negotiations with Albania if no solution is reached.

Finally in 2014, Greece took a symbolic move demonstrating its lack of support for enlargement, when it excluded enlargement from its EU Presidency priorities. Previous initiatives by high-ranking officials, such as Prime Minister Papandreou’s 2009 plan to integrate the western Balkans into the Union by 2014 had lost their practical meaning.

A changed, more flexible Greek position on the bilateral issues is a precondition for progress of the three candidates towards the EU. As long as it remains part of the Union – and that last resort has not been discussed in recent months – Europe needs Greek compromises for progress in the western Balkans.

A chance for engagement

The departure of conservative Prime Minister Samaras in 2015 raised hopes that talks on bilateral issues could find a new dynamic. Already in the 1990s, he represented the most uncompromising faction in the dispute with Macedonia.

The Syriza-led government, in power since January 2015, does not bear the burden of past governments, led by historically well-established political parties. Syriza, a far left non-nationalist party, is potentially far more flexible. How- ever, after coming into office, the government’s policy has adapted to the mainstream Greek foreign policy by shifting the foreign policy portfolio to its nationalist coalition partner, Independent Greeks.

However, the Syriza-led government has recognizably changed the tune in bilateral relations. In September 2015, Prime Minister Tsipras met his Macedonian counterpart to talk about the name dispute on the fringe of a UN conference in New York. Also the Foreign Ministers have met several times in the last year to discuss the matter. 2015 saw a high-ranking Macedonian minister visiting Greece for the first time since 2000. The tune has also changed towards non-recognized Kosovo. Greek Foreign Minister Kotzias reiterated support for Kosovo’s process towards membership in international organizations and integration in the EU. A comparable development seems possible in the future towards Albania.

As important as the changes on the Greek side are movements on the other side of the table. Macedonia has recently shown signs of ceding further ground to Greece on the name issue. In addition, the country will see early elections by summer 2016, hopefully overcoming its political crisis. At the same time, a new government could mean a more flexible approach finds its way into office. More than 80 percent of Macedonians still support the path towards EU accession.[1] Whoever heads the next government will feel pressure to advance towards the EU. Progress in the name dispute will bring a new dynamic to the EU accession track with the population recognizing the government’s achievement. Similar motives will also provide an incentive for governments in Albania and Kosovo to aim for progress in their disputes with Greece.

The western Balkans provide Greece with an opportunity to improve its international standing through better relations with its neighbors, which suffered badly during the economic and refugee crisis. But the EU’s engagement on the issue is needed, as soon as opportunities open up. The situation is not conducive for engagement yet. Forcing Greece to make concessions in the region in exchange for flexibility on economic measures or migration will not be sufficient. According to media reports, this approach already has failed in the summer of 2015 with EU officials trying to strike a deal on Kosovo with Greece. However, the interconnectedness of political developments in Greece can also lead to an engagement of the Greek government on the regional issues. First, political conditions need to normalize and Greece needs to feel that is being treated as a European partner again. The government needs to show political successes at home. These can only be realized with European support. On the most pressing issues, the migration crisis and the Eurozone crisis, Greece has recently become isolated, with solutions considering exclusion or circumvention of Greece.

The migration crisis’ impact

The ongoing migration crisis has severe consequences for the Balkan states, contributing to instability in the region and straining the states’ capacities. Better crisis management is what the European actors are currently trying to establish. This is also a precondition for progress between Greece and the western Balkans. For the western Balkans, a better handling of the migration crisis would eliminate a destabilizing element. The region became, while completely unprepared, a transit corridor for migrants to the north of Europe. Still, the situation is tying down resources that are well needed for internal crisis management. Macedonia in particular, bordering Greece on the north and still on the frontline of the crisis; would profit from a regularized process of migration on the Turkish-Greek border and within Greece. A focus on other political fields would become possible.

Talks on regional issues would also be facilitated. This is the logical consequence of the most promising approach to crisis management. For the situation to improve, it is crucial that Greece needs to deliver on migration. Reception capacities need to be improved, a functioning registration system has to be established and an operative border control system needs to be put in place. Much of this is achievable with EU member states’ assistance and with enhanced Frontex engagement. However, all these improvements can only be implemented if Greece, in addition to Turkey, is convinced of the validity of the measures and thus shows a will to comply with them. The deployment of Frontex, in this exceptional case, on the Macedonian-Greek border is a case in point. Greek reluctance to implement certain measures in the refugee crisis can be seen as an attempt to keep a bargaining chip in case the Union moves in the direction of sanctioning Greece. Athens is worried because the Commission’s Schengen Evaluation Report on Greece has mentioned that the country “is seriously neglecting its obligations under the Schengen rules and that there are serious deficiencies in the carrying out of external border controls”. It is only a credible partnership that will lead the country away from this policy. The operationalization of the EU commission’s recommendations and assessment of their implementation is expected to finish by the end of the summer. It will be a decisive moment in the normalization of relations between Greece and the EU on migration.

A need for enabling conditions

A political or economic collapse of Greece will prevent an engagement with Macedonia, Kosovo and Albania for the conceivable future. The hope of the region’s countries to join the EU will be shattered due to Greek inability to engage on EU enlargement. Greece used to be a role model for European integration for the region. Today, this seems to be a situation from a distant past. However, putting the blame on Greece for the recent Eurozone and migrant European crisis would not solve the problem. Negative policies towards Greece have a direct influence on the western Balkans. Greece should be seen not only as a troublemaker, but as a potentially positive regional factor and be treated accordingly. Imposing solutions will lead to Greek resistance or half-hearted implementation, as we have seen numerous times before with regards to the financial crisis, contributing to a further deterioration of the situation. The EU and its northern member states therefore have to treat Greece as a partner on migration issues, not as a mere subordinate. In return, Greece will be able to engage on the western Balkans; thus, creating a positive dynamic for the resolution of outstanding foreign policy issues with the region. With the removal of bilateral issues, the EU would regain leverage on internal reforms in these countries that it has somehow lost in recent years due to the blurring accession perspective.

Notes

[1] International Republican Institute survey poll 2015. external pagehttp://www.iri.org/resource/iri-poll-macedonians-concerned-about-economy-political-stability-support-representativecall_made (13 July 2015).

Further Reading

How is the sovereign debt crisis affecting Greece’s relations with the Balkan countries and Greece’s standing in the region? Ritsa Panagiotou and Anastasios I. Valvis, Athens 2014.

A comprehensive overview on the effects of the Greek crisis on the eco- nomic and political links to the Balkans until 2014.

T. Dokos,“Greek foreign policy under the Damocles sword of the economic crisis”, No. 2, Konrad Adenauer Stiftung, Berlin, 3 April 2015. The brief offers an analysis of current developments in Greek foreign policy.

BiEPAG,“Removing Obstacles to EU Accession: Bilateral disputes in the Western Balkans”, Policy Brief, August 2015.

The study explores the bilateral disputes in the western Balkans that hinder the EU integration process and offers possible solutions.