A Nuclear Deal for Pakistan?

14 Mar 2016

By Jonas Schneider for Center for Security Studies (CSS)

This article was originally published by the Center for Security Studies (CSS) in March 2016.

Pakistan wants to join the Nuclear Suppliers Group (NSG) in order to enhance its global status. For the first time, the US has now signaled support for this goal – but only if Pakistan in return agrees to limit its nuclear weapons program. No agreement is in sight. However, Pakistan’s intention to respect the rules of global nuclear commerce should be seen as a positive step.

South Asia is faced with the danger of an escalating nuclear arms dynamic. Both India and Pakistan conducted nuclear tests in 1998 and have since expanded their nuclear arsenals. This development is taking place in the context of a longstanding rivalry between the two countries fed by the Kashmir conflict. Even after both states have acquired nuclear weapons, the Indo-Pakistani antagonism continues to manifest itself in terrorist attacks and serious military crises. As a result, the risk of nuclear weapons being used is probably greater in South Asia than anywhere else in the world.

Neither India nor Pakistan are signatories of the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT), which only recognizes the US, Russia, the UK, France, and China as nuclear weapon states. Due to their status as non-members of the NPT, the two South Asian nuclear powers are not bound by the same nuclear disarmament pledges as the nuclear-armed states that are NPT members. On the other hand, Pakistan and India as nuclear-armed non-members may not participate in international nuclear commerce.

Since neither India nor Pakistan are allowed to join the NPT while they retain their nuclear weapons, both countries are trying to overcome their outsider status with regard to the nuclear non-proliferation regime by way of the Nuclear Suppliers Group (NSG). The NSG establishes rules for exporting technology and materials that can be used for building nuclear weapons. With US support, Delhi already succeeded in 2008 in obtaining for itself an exception to the NSG rules. Ever since, this nuclear deal has allowed India to procure nuclear goods form NSG states. Moreover, since 2010, India has been trying to join the NSG as a member. Pakistan, too, would like to join the NSG. As members, both Pakistan and India could take part in shaping the rules of global nuclear commerce and would thus establish them- selves at least to a certain extent as “normal” nuclear weapons states on the international stage.

Membership in the NSG is tied to NPT membership. However, the US supports India’s membership bid even without NPT membership. Washington has hitherto portrayed this partial weakening of the international nuclear regime in favor of India as a one-off exception. However, the administration of US President Barack Obama now plans to support Pakistan’s bid to join the NSG, too, although this offer is predicated on a limitation of Pakistan’s nuclear arsenal.

(Click to enlarge)

Such a nuclear deal with Pakistan would be significant in two ways. First of all, it raises the question of whether and under which conditions “nuclear outsiders” such as Pakistan should be (re-)integrated into the non-proliferation regime. Secondly, the nuclear agreement with Pakistan as envisaged by the US is a rare, specific initiative for reducing the danger of a nuclear arms race in South Asia.

Any nuclear deal with Pakistan is closely linked to India’s possible accession to the NSG. For after joining the NSG, India could permanently block an NSG accession of its Pakistani rival. In view of this veto right, however, the conditions for both India and Pakistan joining the NSG can be influenced by all 48 NSG members, including Switzerland.

India’s Nuclear Deal

All deliberations on a nuclear agreement with Pakistan are predicated on the US nuclear deal with India. In 1974, India was the first state after the five recognized nuclear weapons states of the NPT to carry out a nuclear test. Subsequently, it was shunned for decades as an illegitimate nuclear state and largely excluded from civilian nuclear commerce. It was only in 2008, when the NSG members, prompted by the US administration of George W. Bush, agreed to make an exception from its rules to allow civilian nuclear trade with India, that the country was to some extent readmitted into the global nuclear order.

In return, India had to back up its claim to be a responsible “normal” nuclear weapon state with a series of steps demonstrating its commitment to non-proliferation: It had to separate its civilian nuclear facilities strictly from its military nuclear facilities and place all the former under International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) safeguards. Also, India’s regulatory framework on export controls was adapted to the guidelines of the NSG and the export control regime for biological and chemical weapons. Moreover, Delhi has committed itself to a continuation of its nuclear test moratorium and to supporting negotiations on an international Fissile Material Cut-Off Treaty (FMCT). Informally, India also appears to have signaled that it will only expand its nuclear arsenal very moderately in the future.

Beyond these non-proliferation concessions, support for an agreement with India among several NSG member states seems also to have been based on additional considerations. For instance, in the US, the prospect of strengthening India’s position vis-à-vis China while simultaneously intensifying relations between Delhi and Washington by way of the nuclear deal seems to have played an important role. At the same time, the outlook for lucrative sales of nuclear power plants to India has clearly raised the willingness among major nuclear exporting nations to turn a blind eye to India’s nuclear weapons to some extent. Under the terms of the 2008 agreement, however, the question of India’s admission to the NSG was not yet discussed at all. Delhi has only been pursuing the goal of NSG membership since 2010.

From the Pakistani point of view, the Indian nuclear deal and Delhi’s aspirations to join the NSG have been devastating. On the one hand, Islamabad fears that India could rapidly step up its production of weapons-grade fissile material. Pakistan believes that since India, having secured access to global nuclear trade, can now procure uranium for its civilian nuclear program on the world market, its domestic uranium resources can be funneled exclusively to the Indian nuclear weapons program. On the other hand, India’s partial admission into the global nuclear order has triggered massive status concerns among Pakistan’s elites, who constantly strive for parity with India. The upshot of this two-fold apprehension is that Pakistan has accelerated its nuclear armament program even more, while simultaneously demanding a nuclear deal for itself, too.

Pakistan’s Nuclear Armament

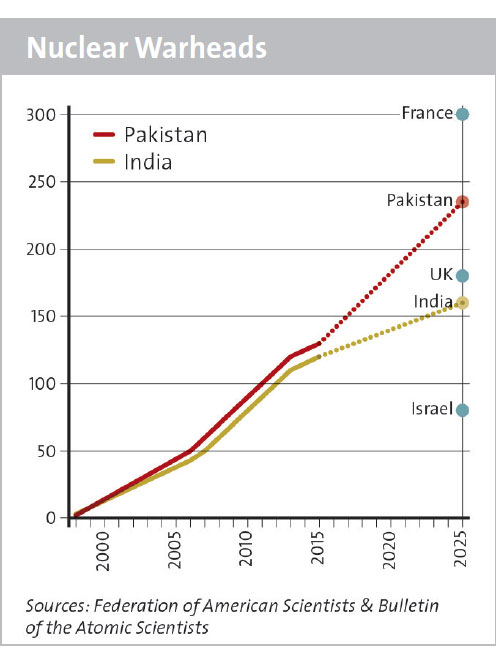

For a number of years, Pakistan has been rapidly stepping up its nuclear arms procurement. Experts estimate that Pakistan already possesses more nuclear warheads than India. Moreover, since Pakistan’s nuclear arsenal is growing much faster than that of India, this divergence will increase even more. Additionally, assuming that this dynamic continues, Pakistan’s nuclear arsenal will in ten years exceed that of the UK as well (cf. box).

Pakistan’s nuclear doctrine has also changed. In the past five years, Pakistan’s military has lowered the threshold for nuclear weapons use by increasingly relying on tactical nuclear weapons as part of its nuclear first-use policy. The newly developed, nuclear-capable “Nasr” short-range missile with a range of 60km is mainly intended for battlefield use. Pakistan has already produced large numbers of the Nasr missile and recently begun deployment. With tactical nuclear weapons such as these, the Pakistani military hopes to compensate for its conventional inferiority vis-à-vis India. Pakistan has therefore announced that, should the feared scenario of a surprise conventional attack by Indian forces materialize, it would retaliate at an early stage with tactical nu- clear weapons. It hopes that this doctrine will deter such an attack by India.

However, there are specific dangers arising from Pakistan’s tactical nuclear arms – especially in combination with the willingness to use them early in a conflict. This relates firstly to the physical security of the weapons. In order for tactical nuclear weapons to have the intended deterrent effect, they must be mated with delivery systems and deployed as close to the likely battlefield as possible. Also, decision-making authority for their use should be delegated to a frontline commander in advance.

This, however, inevitably diminishes the ability to prevent nuclear theft or the unauthorized use of the weapons during crises. In view of the extremist groups operating in Pakistan, and of the numerous Pakistani military commanders who sympathize with those groups, the risks seem considerable.

A second set of dangers arises from the enhanced escalation risks resulting from different assessments about the credibility of Pakistan’s use of tactical nuclear weapons. Pakistan’s military may be convinced that Delhi regards the use of tactical nuclear weapons by Pakistan in the event of a conventional Indian attack as credible (and will thus be deterred from carrying out such an attack). The Indian side, however, has described Pakistan’s threat of employing tactical nuclear weapons in the case of a limited invasion as not credible – not least because Delhi itself has threatened massive nuclear retaliation even in the event of a nuclear strike against Indian forces located on Pakistani territory. Pakistan, in turn, has stated that it seriously doubts the likelihood of such a reaction. Even a limited conventional attack by India could thus unintentionally escalate into a strategic nuclear exchange between the two countries. In particular, such an escalation might also be triggered by attacks by Pakistani terrorist groups such as Lashkar- e-Taiba (LeT) against targets in India, if Indian forces were to respond with force against LeT targets on Pakistan’s territory. These escalation risks, together with the difficulty of physically protecting Pakistan’s tactical nuclear arms, have been major factors in the US initiative for a nuclear deal.

Obama’s Proposal

The Obama administration, after a series of talks, made Pakistan a concrete offer for a nuclear agreement in the run-up to a bilateral summit in October 2015. This proposal appears to envisage that Pakistan should agree to limit its nuclear arsenal to such weapons types and to deploy only such delivery missile platforms as are necessary for deterring, or defending against, the nuclear threat emanating from India. Pakistan’s ability to deter Indian nuclear attacks stems primarily from its own strategic nuclear forces. If the US had its way, Pakistan would thus strictly limit the number of its tactical nuclear weapons and end the development of these weapons. Pakistan would then “mothball”, i.e., refrain from deploying, the Nasr missiles it has already produced. Moreover, Pakistan would not be allowed to deploy any missiles with a range extending beyond India’s territory (and thus including Israel).

(Click to enlarge)

In return, the Obama administration is apparently prepared to support Pakistan’s bid for admission to the NSG. This would allow Pakistan to have access to international nuclear commerce and have an equal vote in determining its rules. However, Pakistani membership in the NSG would be beneficial to other countries too, since, once admitted to the NSG, Pakistan would be integrated into the intense sharing of intelligence on nuclear exports among the member states, which would be advantageous to all parties concerned. Moreover, as an NSG member, Pakistan would be bound more closely to the group’s export guidelines, which also stipulate a de-facto moratorium on exports of sensitive technologies such as those used for uranium enrichment and plutonium separation. Bearing in mind the often-discussed scenario of Pakistan potentially passing on sensitive nuclear technology to Saudi Arabia, this step towards strengthening Pakistan’s commitment to nonproliferation would be a good idea. Against this background, the NSG has already set up outreach meetings with Pakistan regarding its exports.

The NSG and Pakistan

Admission to the NSG would give Pakistan “green light” to participate in the global trade in nuclear technology and materials. However, from a purely economic perspective, accession to the NSG is hardly attractive for Pakistan. For already today (despite its nuclear arsenal, which violates the NPT), Pakistan receives nuclear power plants from China, which is thus in violation of its own NSG obligations (Beijing’s argument that it is now merely fulfilling a delivery commitment to Pakistan that was made before China joined the NSG in 2004 is not tenable). The other member states would most likely not engage in civilian nuclear trade with Pakistan even in the event that the country was to join the NSG. The country’s credit-worthiness is so diminished that financing of nuclear projects in Pakistan is out of the question purely on economic grounds. Only China is willing to do so – based on geopolitical considerations.

Islamabad’s interest in NSG membership is mainly motivated by considerations of status. Joining the group would underline Pakistan’s claim to parity with India at the bilateral level, while sending the message internationally that the country is accepted as a responsible, “normal” nuclear weapons state. However, this prospect of enhanced status for Pakistan is exactly why the idea of a nuclear deal with Pakistan will probably be met with serious reservations on the part of the other NSG member states. Most of them plainly do not view Pakistan as a responsible nuclear weapons state, for two reasons: First of all, the country still suffers from the reputational damage caused by the A.Q. Khan proliferation network, which sold uranium enrichment technology and blueprints for nuclear warheads to Iran, Libya, and North Korea until 2003. The Pakistani state was involved in this nuclear smuggling business at least through tacit acquiescence; moreover, to this day, Islamabad refuses to conduct a full and open investigation of these cases. Secondly, many are skeptical about the prospect of a nuclear deal because the support extended by parts of the Pakistani security establishment to anti-Indian terrorist groups such as LeT is viewed as irresponsible by many states, considering the risks of nuclear escalation.

Added to this is the fact that – unlike with the deal secured by India in 2008 – the concerns about security and proliferation in the case of Pakistan are not alleviated by the prospect of lucrative sales of nuclear power plants. Moreover, the agreement with India was tied to hopes of strengthening Asia’s democracies vis-à-vis China; there is no comparable outlook in the case of Pakistan, which is only partially democratic and also closely aligned with China. For all these reasons, Islamabad – unlike India in 2008 – will most likely have to make concessions regarding its military nuclear program if it wants to come to an agreement with the NSG. Such concessions will center on its tactical nuclear weapons. Furthermore, it is conceivable that NSG states will raise demands for Pakistan to become more flexible and step away from its hardline rejection of an FMCT and the Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty (CTBT).

Pakistan’s Position

Delhi and the Obama administration share the view that India should be accepted as an NSG member without restrictions on its nuclear arsenal and based on the non-proliferation concessions it made in 2008. If India is to be admitted to the NSG, Pakistan demands that it should be allowed to join on the same terms. For Pakistan already meets most of the non-proliferation criteria that India had to fulfill for the 2008 agreement: All Pakistani research reactors and nuclear power plants are subject to IAEA inspections, thus meeting the requirements for a separation of civilian and military nuclear facilities. Pakistan’s export control laws and regulations, and the country’s export control decision-making process were also reformed and adapted to international standards after the A.Q. Khan scandal. Furthermore, Pakistan has already instituted a moratorium on nuclear tests. It is also conceivable that the country may adopt a more flexible position regarding FMCT negotiations – without committing itself to joining a treaty regime.

The crux of a nuclear deal with Pakistan is that the US and most of the other supplier countries will demand concessions from Pakistan regarding its tactical nuclear weapons in return for admission to the NSG: Washington regards Pakistan’s growing arsenal of tactical nuclear arms as one of the main threats to stability in South Asia. The Pakistani military, on the other hand, views these weapons as indispensable for deterring limited conventional invasions by India.

The assumption by Pakistan that tactical nuclear arms are effective in deterring an enemy who enjoys conventional superiority is controversial, but cannot be disproven. However, this supposed feature of tactical nuclear weapons is fraught with grievous risks – as even NATO has found out: In a process that began in the late 1970s, the alliance withdrew almost its entire tactical nuclear arsenal from Europe because the security risks associated with these weapons and the large numbers of allied civilian casualties their use would have inflicted were judged to be unacceptable. Thus, the argument often cited by the Pakistani military that tactical nuclear weapons were an indispensable element of NATO’s military strategy is only partially applicable.

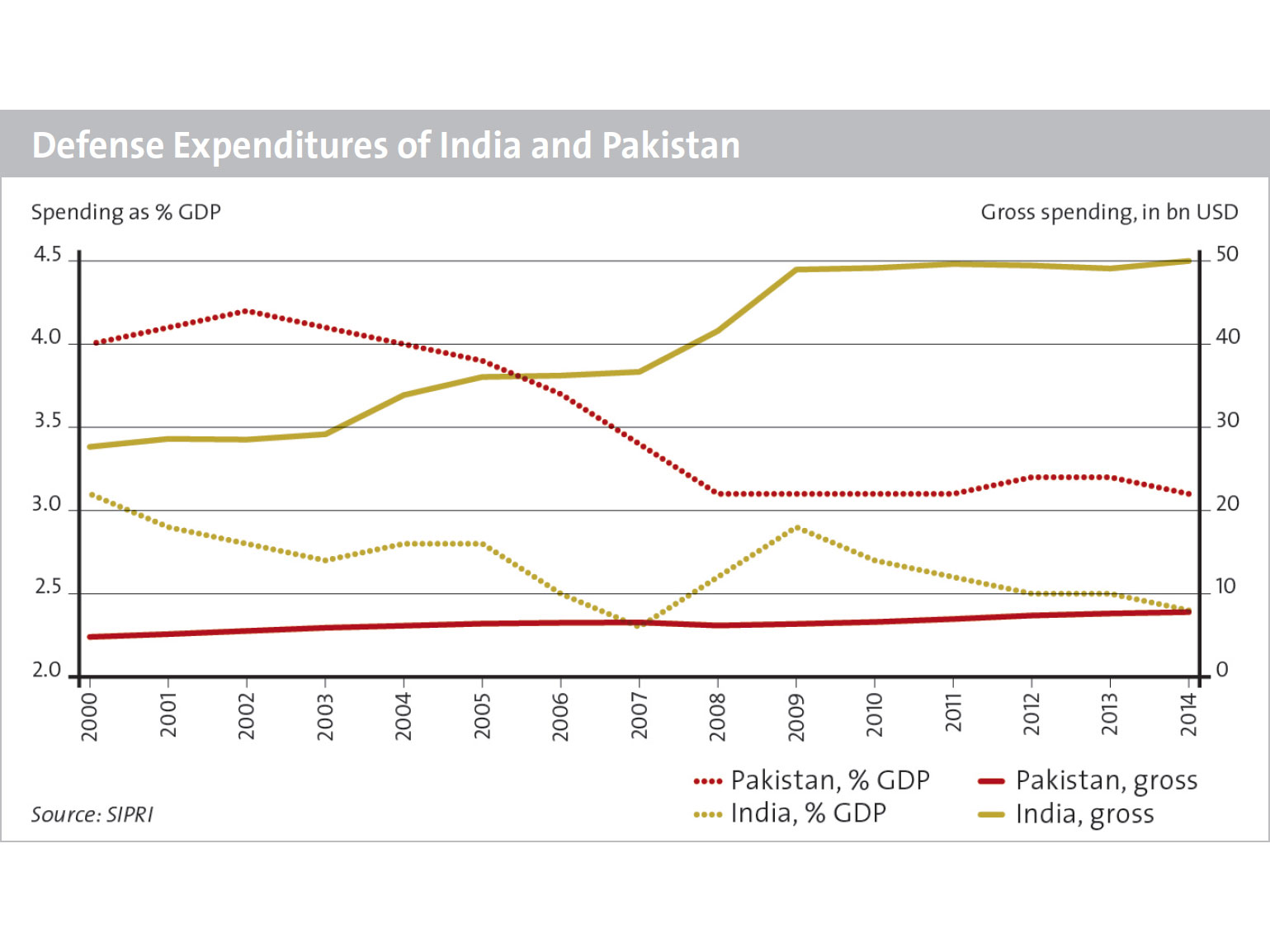

A further risk for Pakistan is that a steady expansion of its tactical nuclear arsenal could cause India to follow suit. However, in the ensuing arms race, Pakistan could only lose: India’s economy is ten times the size of Pakistan’s, and Delhi’s defense expenditures are five times as high as those of Islamabad (cf. box above). Therefore, limiting its nuclear program would also be in Pakistan’s interest. However, so far, Islamabad appears willing to incur both the risk of a nuclear arms race and the risk of severe destruction in the case of its tactical nuclear weapons being used on Pakistani soil in order to deter a perceived threat from India.

Annex 1

Switzerland and NSG Admission

India’s government aspires to secure approval for its membership in the NSG at the next annual meeting of the group in June 2016. However, no consensus on India’s admission is discernible yet among the NSG member states: For Switzerland – as well as a number of other European states, including Austria and Ireland – there are still many questions that remain to be answered. Its views on India’s desire for membership – as well as a possible nuclear deal with Pakistan – are primarily predicated on the question of how the NSG should generally handle relations with the four nuclear weapons states that remain outside the NPT (India, Pakistan, Israel, and North Korea). Regarding admission of these states to the NSG, Switzerland prefers that the NSG should lay out clearly defined criteria that would strengthen the non-proliferation regime and would be equally applicable to membership bids from all four of these countries. Berne is of course aware that before such a regime for granting membership could be introduced, some of the most difficult questions of nuclear policy and procedural matters would need to be resolved.

Decisions are unlikely to be made in the near term. For China is opposed to admitting India while its ally, Pakistan, is refused membership on the same terms – irrespective of the nature of those conditions. Unless China receives assurances from the NSG states that Pakistan would also be allowed to join, Beijing will veto India’s admission. There is therefore no need at this point for Switzerland to make a final commitment one way or the other concerning admission of India and/or Pakistan to the NSG.