The Renationalization of European Defense Cooperation

21 Mar 2016

By Daniel Keohane for Center for Security Studies (CSS)

This chapter of CSS' Strategic Trends 2016 can also be accessed here.

European governments need to cooperate on defense matters. Orthodoxy holds that this cooperation should be directed by NATO and the EU. In fact it is national governments that are driving European defense cooperation, and they are doing so in a variety of ways. Their methods include bilateral, regional and ad hoc arrangements, as well as working through the Brussels-based institutions. The success of European defense cooperation, therefore, will depend on the convergence or divergence of national policies.

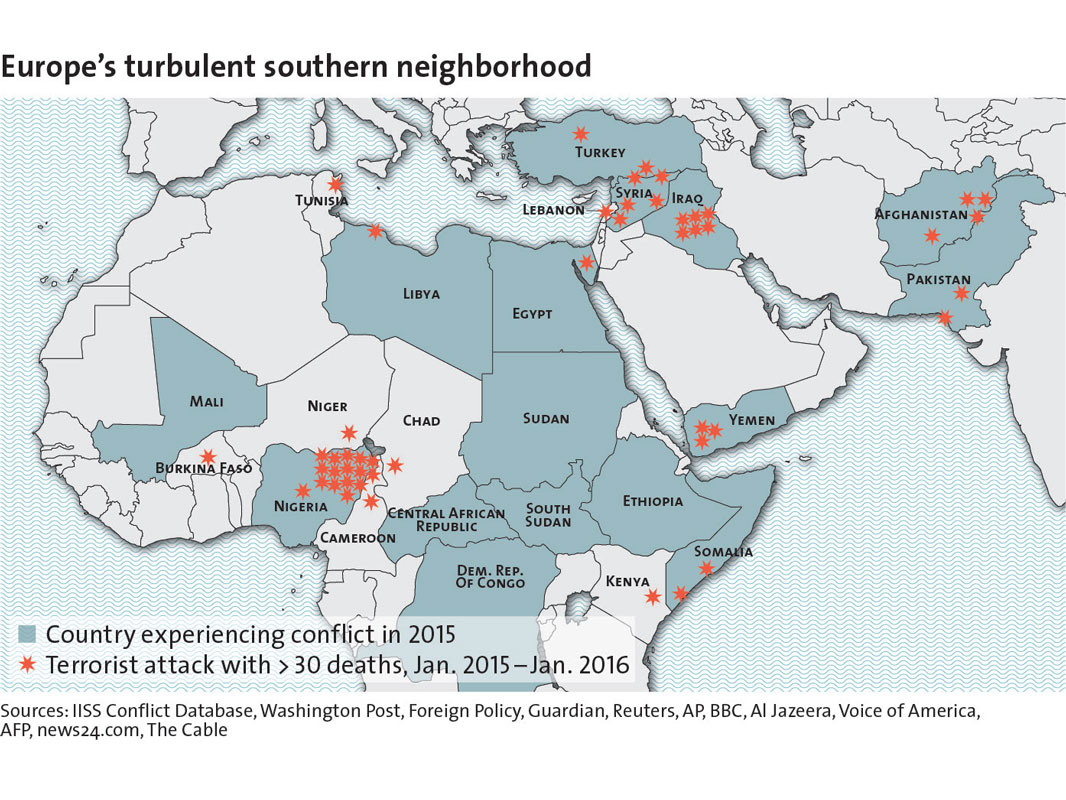

Europeans face a complex confluence of security crises, which may further overlap and intensify during 2016. These include an unstable Ukraine and an unpredictable Russia; a fifth year of war in Syria, which has generated extensive refugee flows into the European Union; the emergence of ISIS in Syria and Iraq, which has created a new terrorist threat within the EU; and state failure in Libya, where ISIS-aligned militants are increasingly active and large numbers of migrants and refugees have passed through on their way to Europe.

Aside from their complexity, one key new dimension of this set of security challenges is that Europeans now have to defend their territories and manage external crises simultaneously. Another important aspect is that the lines between internal and external security are increasingly blurred.

Against this backdrop, the EU is expected to adopt a new ‘global strategy’ at a summit in June 2016, which will set out priorities and guidelines for EU foreign, security and defense policies. A few weeks later the North Atlantic Treaty Organization will hold a summit in Warsaw, where its members will discuss the Alliance’s role in coping with Russian aggression in Eastern Europe and disorder across the Middle East.

These institutional processes are extremely important for European defense cooperation, since European governments need to cooperate with each other. But European defense cooperation will be driven more by the coming together of national priorities than by the efforts of institutions such as the EU and NATO. European security and defense cooperation will continue, but it will be mainly bottom-up – led by the national governments – not top-down, meaning directed and organized by the institutions in Brussels.

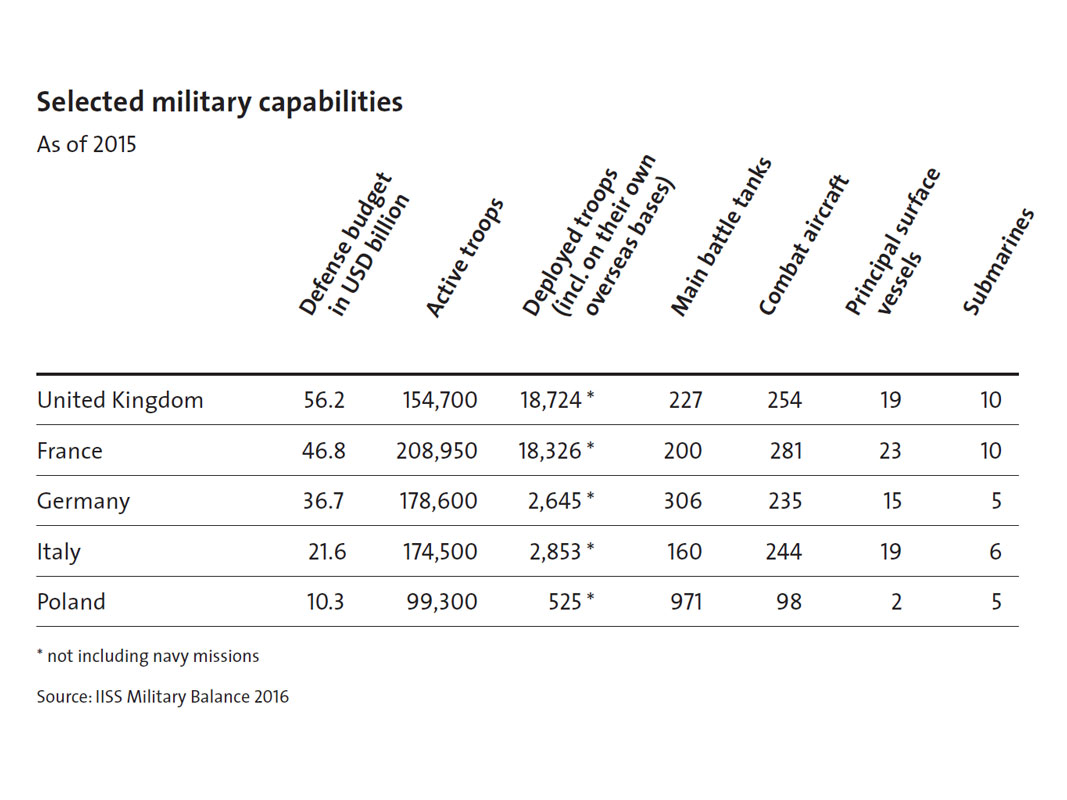

Furthermore, the ‘Big 3’ – France, Germany and the UK – aim at substantially higher levels of defense ambition, whereas other European governments are forced to prioritize. And sometimes national priorities diverge decisively. This poses tremendous challenges for European defense cooperation, but it may also provide a framework for more fruitful cooperation.

National governments retake center stage

The EU and NATO should and will continue to encourage deeper European cooperation, not only to help avoid excessive fragmentation or duplication of European collaborative efforts, but also to coordinate and support disparate national policies.

However, European defense cooperation is increasingly driven by the coming together of national defense policies in various different ways rather than by the efforts of European or trans-Atlantic institutions alone.

Institutional orthodoxy

Considering the range of security crises that Europeans face, the case for deeper European military cooperation is strong. For one, there has been mounting ambiguity over the role of the United States across the EU’s neighborhood, although there is currently an intense debate in the US about increasing the American military presence in Europe and the Middle East. The Obama administration announced in February 2016 that it plans to quadruple its military spending in Europe, and to increase the budget for its anti-ISIS campaign by 50 percent. Even so, the US appears unwilling to manage all the crises across Europe’s neighborhood, meaning Europeans may sometimes have to respond without American leadership or assistance.

For another, no single European country has the military resources to cope with all the crises alone. European defense budgets have been cut considerably since the onset of the economic crisis in 2008. According to the most recent figures from the European Defense Agency (EDA), national defense budgets in the EU decreased by around 15 percent between 2006 and 2013. The good news is that in early 2016 (in his Annual Report 2015) the NATO Secretary-General announced that the decline in European defense spending has now stopped.

Institutional orthodoxy in the EU and NATO holds that reduced national defense budgets, especially for equipment, should surely spur more cross-border collaboration. European armed forces have a number of capability shortfalls, such as intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance equipment, and the cost of advanced equipment typically rises by around 5 percent a year. This message has not reached the national capitals. Between 2006 and 2011 EU governments spent around 20 percent of their equipment budgets on pan-European collaboration each year – by 2013 this figure had fallen below 16 percent, according to the EDA. Just over 2 percent of the combined defense spending of EU governments is spent on European collaborative equipment procurement.

Similarly, European governments have become less willing to send soldiers abroad for peacekeeping operations, and more selective about which missions they participate in. The average number of soldiers EU governments sent abroad fell from about 83,000 in 2006 to just over 58,000 in 2013. All the European members of NATO contributed to its operations in Afghanistan during the 2000s, but less than half participated in NATO’s 2011 military intervention in Libya. The EU has deployed around 30 peace operations since 2003, but 24 of these were initiated before 2009, and the pace and size of new missions has dropped considerably since then. In addition, Europeans accounted for less than 7 percent of the 90,000 United Nations (UN) peacekeepers deployed during 2015.

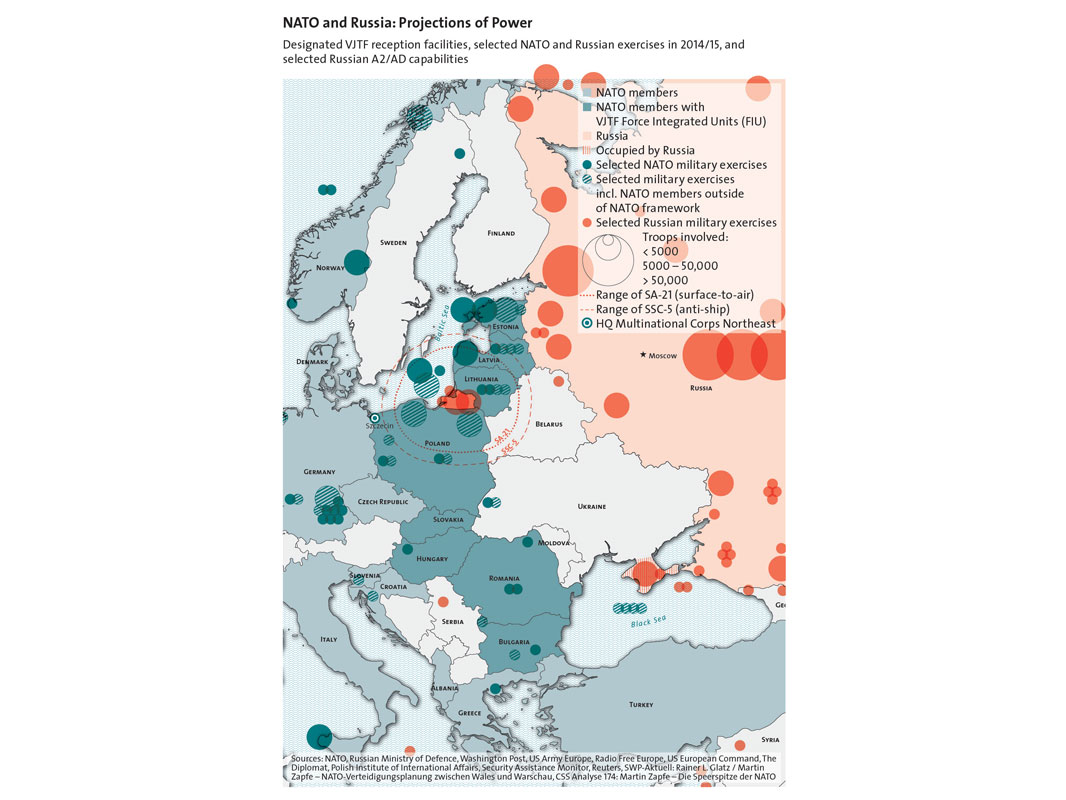

It is true that NATO’s central role in European territorial defense has been reinvigorated since 2014 by Russia’s aggression in Ukraine. Conventional deterrence is back in Europe, as a core task for European governments. But so far even these efforts have remained relatively modest. With a strength of only 5,000, the headline NATO formation for responding to Russian revisionism in Eastern Europe, the multinational Very High Readiness Joint Task Force (VJTF, within the broader NATO Response Force) prompts questions about its usefulness in some military scenarios. According to a 2016 RAND war-gaming study, the longest it would take Russian military forces to reach the Estonian and/or Latvian capitals of Tallinn and Riga would be 60 hours.

Regional clusters, bilateralism & ad hoc coalitions

However, even if the EU and NATO are struggling to encourage much deeper collaboration between their members, it would be wrong to think that there is no progress on European defense cooperation. For example, according to a June 2015 analysis from the European Union Institute for Security Studies (EUISS), in early 2015 there were nearly 400 ongoing military cooperation projects in Europe. These include initiatives such the European Air Transport Command in the Netherlands, which manages the missions of almost 200 tanker and transport aircraft from seven countries, and the Heavy Airlift Wing based in Hungary, which has helped 11 European countries procure and operate a fleet of C-17 transport planes.

Some countries are also working more closely in regional formats, such as Baltic, Nordic and Visegrad cooperation. And a number of European governments are pursuing deeper bilateral cooperation, including integration of parts of their armed forces in some cases. Examples include Franco-British, Belgian-Dutch, German-Dutch, Polish-German and Finnish-Swedish initiatives, amongst others. A few European governments, such as France, Spain and the United Kingdom, are also deepening their bilateral cooperation with the US.

(Click to enlarge)

Cooperation on operations has also become more ad hoc in recent years. The 2011 military intervention in Libya began as a set of national operations (run by France, the UK and the US) that were later transferred to NATO command. France intervened alone in Mali and the Central African Republic during 2013 (with some equipment assistance from allies like the US), both of which were followed by (small) EU capacity-building missions and UN peacekeeping operations. And the current coalition bombing ISIS in Syria and Iraq is exactly that: a coalition of the willing. Furthermore, the UK and Germany only stepped up their contributions to the anti-ISIS coalition following the November 2015 terrorist attacks in Paris. At the time of writing, another coalition of four countries – Britain, France, Italy and the US – was considering intervening in Libya to attack ISIS-aligned militants there.

Renationalizing cooperation

European governments are increasingly picking and choosing which forms of military cooperation they wish to pursue, depending on the capability project or operation at hand. Sometimes they act through NATO and/or the EU, but almost all European governments are using other formats as well, whether regional, bilateral or ad hoc coalitions of the willing. The combination of more complex security crises and reduced resources has meant that European governments are more focused on their core national interests than before, and both more targeted and flexible on how they wish to cooperate.

In many ways this renationalization of European defense cooperation is not new. As the aforementioned EUISS analysis put it, European defense collaboration is going ‘back to the future’, in that most major collaborative projects initiated from the 1960s to the 1990s – such as Eurofighter jets, A400M transporters and the Eurocorps – were ad hoc inter-governmental projects. The difference today is that more European defense cooperation is needed because Europeans face a wider range of complex threats and have significantly reduced resources for their defense. National priorities are driving European defense cooperation, which is why analyzing disparate national policies helps to understand the potential for greater convergence or divergence of those policies, and the prospects for deeper European defense cooperation.

The ‘Big 3’, Italy and Poland

This section shows the diversity of national defense policies in Europe, by surveying five countries – the United Kingdom, France, Germany, Italy and Poland. These five were selected based on their size (strength of armed forces, defense budgets and percentage of GDP spent on defense), membership of both the EU and NATO, and geostrategic priorities. Other major European countries – such as Spain, Turkey, the Netherlands, Romania and Sweden – are beyond the scope of this chapter, but they are no less important for European defense due to this. For each of the five countries surveyed, the basic outlines of their geostrategic and operational priorities, institutional preferences, and main capability investments are considered.

It becomes clear that the ‘Big 3’ are increasingly ambitious and aim to cover the full spectrum of military tasks, although there are some differences between them over geostrategic priorities, institutional preferences and willingness to contribute to some types of operations. All the others, basically, have to pick and choose, and their choices are dramatically diverse: Whereas Poland is looking east, Italy is focused almost exclusively on the south. While clear in their priorities, the relative narrowness of outlooks of most European governments compared to the ‘Big 3’ can strain the institutional frameworks for cooperation, whether NATO or the EU.

The United Kingdom – towards full-spectrum and global

In November 2015, the UK published a new security and defense review. In recent years, some NATO allies and international security experts criticized the UK for not contributing as much as it could towards tackling the growing number of crises in and around Europe. Having been long-considered Europe’s leading military power (alongside France), the image of Britain as a declining military power had taken hold in some expert and political circles, both domestically and internationally. In many respects, the 2015 UK defense review carried out by the Conservative government is a response to these criticisms.

The previous review, carried out in 2010, was inspired more by fiscal austerity than by strategic concerns: The economic crisis had caused the government budget deficit to quadruple between 2007 and 2009. The defense budget was slashed by 8 percent in the five years after 2010, and the army was reduced to its lowest manpower level since the Napoleonic era. The 2015 version is more coherent and ambitious. For example, the 2010 review considered a large-scale military attack by other states to be a “low probability”. Because of intervening Russian aggression in Eastern Europe (alongside other crises and the rise of the Islamic State) since 2010, Britain should now aim to simultaneously deter state-based threats and tackle non-state challenges.

Despite the urgent security crises in Europe’s immediate neighborhood, the 2015 review emphasizes that Britain should keep a global outlook and develop closer military ties with partners in the Asia-Pacific, the Gulf and Africa. Alliances are also heavily underlined in the 2015 review, with a strong emphasis on working through NATO, which the UK considers to be the bedrock of its national defense. The UK intends to remain “NATO’s strongest military power in Europe”, and will continue to contribute to the Atlantic Alliance’s defensive efforts in Eastern Europe, such as Baltic air policing and military exercises.

In addition, the UK intends to deepen its bilateral cooperation with three key allies in particular: the United States, France and Germany. Later this year, for example, a French general will become second-in-command of one of the British army’s two frontline divisions, as part of a permanent exchange of military officers that underpins deepening Anglo-French military cooperation. A section on security cooperation through the EU comes after those covering NATO and bilateral collaboration, stating that the EU has “a range of capabilities to build security and respond to threats, which can be complementary to those of NATO”. London would also like the EU and NATO to work together more effectively in tackling security challenges, such as countering hybrid threats.

For military tasks the review highlights two aspects in particular. One is the ongoing need for strong deterrence capabilities, represented by the continuation of the Trident nuclear program (some members of the main opposition party, Labour, question its usefulness). Another aspect is to be able to respond quickly and robustly to a variety of international security crises, meaning to be able to deploy externally rapid strike capabilities, ranging from special forces to aircraft carrier groups. Longer-term Afghanistan-style counter-insurgency deployments, which had characterized British military operations in the 2000s, are no longer viewed as an operational priority. Instead, projecting military power globally quickly (‘in and out’) and acting robustly will be the main operational priority, alongside a greater emphasis on deterrence.

This fuller-spectrum strategic approach will require resources. London intends to increase defense expenditure by around 5 percent by 2020 and promises to meet the NATO target of spending at least 2 percent of GDP on defense over the same period. Furthermore, Britain will invest GBP 178 billion (USD 262 billion) in military equipment over the coming decade, an increase of GBP 12 billion (USD 18 billion). That money will be spent both on preplanned projects, such as maintaining the Trident nuclear deterrent and developing two new aircraft carriers, and on ways to fill some capability gaps that resulted from the austerity-driven 2010 review (such as maritime patrol aircraft and new combat ships and armored vehicles). Plus, almost 2,000 additional intelligence officers will be recruited to track terrorists and cyberthreats.

This renewed level of British military ambition is important for NATO, as the UK is the largest European defense spender in the Atlantic Alliance. Following recent grumbling by some NATO allies, especially Washington, about Britain’s declining military willingness and ability, the main political message that emerges from the 2015 defense review is that Britain is back as a serious military power. Whether this proves to be the case in practice remains to be seen, as unforeseen events may expose glaring capability gaps or budgetary difficulties may hamper some equipment projects. But the intention is clear.

The 2015 UK defense review is an ambitious defense plan by European standards, but the threat of a British exit from the EU (known as ‘Brexit’) hangs over British strategic ambitions. The UK government has to hold a referendum on its EU membership by the end of 2017, announced for 23 June 2016. Opinion polls in the UK currently show supporters and opponents of a Brexit in a dead heat. In the worst-case scenario, the UK outside of the EU would probably remain a significant military power (depending on the economic fallout), and both a member of NATO and a permanent member of the UN Security Council. But a Brexit would diminish the UK’s standing as a diplomatic player since it would lose influence in Europe, no longer having a say over the EU’s socio-economic, security, defense or foreign policies.

France – global outlook, regional priorities

The main parameters of French defense policy were set out in a White Book published in 2013, which maintained a considerable level of strategic and operational ambition relative to most other European governments, despite its announcement of cuts to French defense spending (from around 1.9 percent to 1.76 percent of GDP) and personnel (24,000). Guaranteeing European and North Atlantic security is considered the second strategic priority (after protecting national territory). Paris has responded to intervening Russian aggression in Ukraine by sending an armored task force to Poland, increasing maritime patrols in the Baltic Sea, and cancelling the planned sale of Mistral amphibious assault ships to Russia.

Beyond Europe, French geostrategic priorities were narrowed in the 2013 White Book, prioritizing Africa (mainly North Africa and the Sahel) and the Middle East from the broader “arc of instability” – stretching across Africa, the Middle East, the Indian Ocean and Central Asia – highlighted in the previous 2008 version. The Indian Ocean was underlined as the next geostrategic priority, while highlighting the potential for strategic trouble in East and South-East Asia. In other words, France intends to be a “European power with global reach”, continuing to strengthen military ties with a number of partners in the Gulf and the wider Indo-Pacific, even if it should prioritize security challenges to Europe’s south.

Following the November 2015 terrorist attacks in Paris, French President Hollande declared that France is “at war” with ISIS, meaning that the geostrategic focus on the Middle East, North Africa and the Sahel has been reinforced. This seems unlikely to change during 2016, but it does put added strain on French defense resources, given increased domestic deployments of French forces and the intensified bombing campaign against ISIS in Syria and Iraq (with perhaps another front to be opened in Libya). Plus, France has been the most internationally militarily active European country over the last five years. Alongside intervening in Libya and Côte d’Ivoire in 2011, Mali in 2013, and the Central African Republic (CAR) in 2013/14, France has kept 3,000 soldiers in West Africa (stationed in Nigeria, Niger, Chad and Burkina Faso) and sent its aircraft carrier, the ‘Charles de Gaulle’, to the Persian Gulf.

As a result the French asked their EU partners to support their anti-ISIS operation and/or relieve French forces elsewhere, such as in Mali or Lebanon. Both Germany (in a support role) and the UK have joined the anti-ISIS bombing campaign in Syria, while (at the time of writing) some other EU partners have indicated that they will send peacekeepers to relieve French forces elsewhere. However, increased domestic and Middle Eastern commitments may reduce France’s ability to contribute substantially to defending NATO territory in Eastern Europe. For example, some 10,000 soldiers have been deployed domestically during 2015 to protect sensitive targets.

(Click to enlarge)

The French invocation of the EU’s mutual assistance clause (article 42.7) in November 2015 also highlights France’s long-standing commitment to a stronger EU defense policy, especially among French Socialists, which form the current government. The 2013 White Book, for example, mentioned the utility of an EU White Paper on defense policy. But for Paris, EU defense should remain an inter-governmental endeavor, which is why it activated article 42.7 and not article 222 (the solidarity clause) which foresees a strong role for EU institutions.

An additional practical reason (amongst others) to act via the EU, rather than invoking NATO’s article V, was to keep open the option of working with Russia against ISIS in Syria. But as their national interventions in Mali and CAR showed, the French do not assume that other European governments will always support their military activities, and Paris is prepared to act alone if necessary. In fact, the most supportive NATO ally of French military actions in recent years has been the US (which, for instance, provided aerial refueling and troop transportation for the Mali intervention).

France also announced during 2015 (after the January ‘Charlie Hebdo’ terrorist attacks in Paris) that the French defense budget would rise by EUR 3.9 billion from 2016 – 2019, resulting in a 4 percent increase in real terms, and keeping French spending at around 1.8 percent of GDP up to 2019. France is spending this money on maintaining its nuclear deterrent (which consumes 12 percent of the French defense budget), and on developing a variety of capabilities to ensure it can continue to project armed force abroad, but with a greater emphasis on intelligence-gathering and rapid response. The overall numbers of fighter jets, tanks and ships (to a lesser degree) are being cut, but some of those capabilities are being replaced with more advanced models – and are being supplemented with more drones, satellites, transport planes, guided missiles and special forces.

Germany – the European pivot

Germany is currently undergoing a defense White Book process that should conclude during the summer of 2016. A set of defense policy guidelines were published by the German defense ministry in 2011, which focused on broadly defined generic threats (rather than country-specific ones) such as failing states, international terrorism, cyber-security and the spread of weapons of mass destruction. It also emphasized the importance of multilateral frameworks, such as the UN and the EU, adding that NATO is the centerpiece of German defense efforts.

Germany’s non-participation in the 2011 NATO bombing campaign in Libya (and its abstention from the UNSC vote on the same) had a negative impact on Berlin’s relationship with its closest allies. Moreover, Germany’s unwillingness to take on combat roles in Mali in 2013 and CAR in 2014 – although it did send trainers and other support assets – fed into an image of a country that was happy to let other Europeans shoulder the heavier military burdens. In early 2014, speeches by the German president, foreign minister and defense minister all underlined that Germany should be prepared to take on more responsibility for international security, including with military means.

In response to the Russian annexation of Crimea in March 2014, Germany not only led European diplomatic undertakings such as placing EU economic sanctions on Russia, but also pledged to reinforce rotating air-policing capacities in the Baltic States, sent a vessel to the NATO naval task force in the Baltic Sea, and doubled its presence in NATO’s Multinational Corps Northeast headquarters in Szczecin, Poland. In addition, Germany has integrated its land forces into NATO’s military exercises scheme to strengthen its troop presence in Eastern Europe. All this is intended to demonstrate Germany’s firm commitment to NATO’s defense and assuring Eastern allies, as well as deterring Russia.

However, in some respects this is not new. West Germany played a crucial front-line role in NATO’s territorial defense during the Cold War. In this sense, there could be a danger that Berlin is now comfortably going back to the future, focusing mainly on NATO’s territorial defense rather than developing a more responsible full-spectrum role in international security.

Yet, the consequences of the November 2015 Paris attacks may influence the 2016 White Book debate on Germany’s participation in external operations. Berlin moved quickly to get parliamentary approval to send reconnaissance and tanker aircraft as well as a frigate to support the intensified French and allied anti-ISIS bombing campaign in Syria. While this is not a full-blown combat role, it amounts to much more than Germany’s previous rather modest support efforts to French-led combat operations in Mali and CAR.

Part of the reason for Germany’s relatively rapid response to French requests for help in fighting ISIS was not only to show solidarity with France, but also to demonstrate its commitment to EU defense policy (alongside its firm commitment to NATO). Although not an EU operation, France formally asked for European support in fighting ISIS via article 42.7, the mutual assistance clause, of the EU treaties. Furthermore, the current German government, a grand coalition of Christian Democrats and Social Democrats, is rhetorically committed to the future establishment of a European army. Whether or not such an army ever comes into being, European cooperation is central to Germany’s worldview and strategy for coping with international security challenges – as stated in Germany’s 2014 foreign policy review.

European military cooperation – indeed integration – is also important for Germany from a more practical viewpoint. Although Germany is boosting its defense spending by around 6 percent by 2019, there remain a number of capability gaps and shortages, especially adequate numbers of usable aircraft (as highlighted in the 2016 German defense ombudsman report). In January 2016, the German Defense Minister announced a plan to invest some EUR 130 billion in defense equipment by 2030. Berlin also strongly pushes for more pooling and sharing of (mostly European) capability efforts, having proposed the ‘Framework Nations Concept’ for deeper capability development within NATO since 2013. Germany is putting its rhetoric into practice by integrating a Dutch mechanized brigade in the German 1st Armored Division, placing a German battalion under a Polish brigade, and investigating ways to further develop the Franco-German brigade.

Italy – looking southwards

Italy is the largest defense spender, by some distance – after Britain, France and Germany – of the remaining European members of NATO (and the EU), and has been an active contributor to NATO, UN and EU operations over the last 20 years. In 2015, Italy produced a new defense White Paper, replacing a White Book published in 2002. The 2015 White Paper is important for a number of reasons, since it lays out Italy’s strategic vision, operational priorities and spending intentions. In particular, the center-left government elected in 2014, led by Matteo Renzi, has been keen to show its reformist credentials, including on defense policy. The document assigns a central role to an interest-based approach to international security, and is unambiguous about the need to use military force, including for deterrence purposes.

Traditionally, Italy has been strongly committed both to NATO solidarity and European integration. The 2015 White Paper places both the EU and NATO on an equal footing for Italy’s contribution to international security. Moreover, NATO’s role is primarily defined in defensive and deterrence terms, both for the defense of national territory and Europe as a whole. The EU is presented as important for Italy in two ways. First, Italy intends to pursue cooperation on capability development more vigorously with other European allies, and the EU – specifically the European Defense Agency – is a vital conduit for such cooperation.

Second, working through the EU is also important for carrying out external operations, since EU defense policy forms part of broader EU foreign policy and mainly performs out-of-area missions. As a result, Italy, like Germany, is more relaxed than some other Europeans about discussing shared European sovereignty on defense matters, such as a stronger role for the European Commission in defense market and research issues.

Italy’s economic difficulties in recent years, coupled with more austere government budgets, has meant that fewer resources are available for Italy’s national defense effort. Italian defense spending as a percentage of GDP fell from 1.3 percent in 2011 to 1 percent in 2015 (according to NATO estimates). The 2015 White Paper, therefore, is very clear on what Italy’s strategic and operational priorities should be. In particular, the ‘Euro-Mediterranean’ region is highlighted as its primary geostrategic focus. This region is conceived in broad terms, covering the EU, the Balkans, the Maghreb, the Middle East and the Black Sea. But it is clear that Italy, which had previously sent troops as far afield as NATO’s mission in Afghanistan, will now primarily worry about its immediate neighborhood.

This is probably not surprising, given the turbulence that has affected some of these regions in recent years, especially North Africa and the Middle East. Turmoil in Libya, for example, has greatly contributed to the large numbers of migrants being smuggled across the Mediterranean to Italy. Interestingly, Italy does not only intend to contribute to international coalitions (whether NATO, UN or EU) in this Euro-Mediterranean space. It is also prepared to lead high-intensity full-spectrum crisis management missions across this region.

In other words, even if the geostrategic priority for Italian defense policy is narrower than for other large European powers, its external operational ambitions remain relatively robust. As three Italian analysts described it in a December 2015 RUSI Journal article, Italy intends to be a “regional full-spectrum” military power. At the time of writing, it seemed that Libya may become the first stern test of the approach outlined in the 2015 White Paper, as an Italian military intervention (probably in coalition with France, the UK and the US) may be required to fight ISIS-aligned Islamist militants in that country.

Poland – looking eastwards

Poland’s geostrategic and operational approach contrasts quite markedly with Italy’s. For one, Poland is primarily geographically focused on Eastern Europe. For another, its operational priority is to improve both national and NATO’s defensive efforts, rather than contributing to robust external missions. Poland for example did not participate in NATO’s air bombing campaign in Libya in 2011. The Russian annexation of Crimea in 2014, following the war between Russia and Georgia in 2008, strongly reinforced a perception in Poland that Warsaw must invest more in its national defense, including through NATO.

(Click to enlarge)

In November 2014, Poland published a national security strategy which makes this defensive focus clear. It stated that “Poland concentrates its strategic efforts principally on ensuring the security of its own citizens and territory, on supporting the defense of allied states … and, afterwards, on participating in responses to threats occurring outside the allied territory”. The national security strategy added that, in line with these strategic priorities, “Poland will focus on measures supposed to consolidate NATO’s defensive function, including strategic strengthening of the eastern flank of the Alliance”.

Poland also wishes to enhance EU efforts in security, in order for “the Union to have adequate security capacities at its disposal, including defense ones”. In other words, Poland favors a stronger EU defense policy, if it can contribute to Poland’s defensive efforts. In addition, the document says that Poland wants to deepen its bilateral military cooperation with the United States, and “will strive for the broadest possible military presence of the US in Europe, including Poland”.

Since 2014, Poland has pushed hard for NATO allies to beef up their military presence in Poland, through exercises and at the Multinational Corps Northeast headquarters in Szczecin, and to implement NATO’s Readiness Action Plan more quickly. Like its predecessor, the new conservative government elected in September 2015 would like NATO allies to install permanent military bases on Polish territory. To help convince more skeptical southern NATO members, who are focused on Middle Eastern disorder, Warshaw signalled in February 2016 that it would be willing to increase its military involvement in the Middle East. That same government will host a NATO summit in July 2016 in Warsaw.

Poland is also putting its money where its mouth is on national defense. According to NATO estimates, Poland met the Alliance’s agreement to commit 2 percent of GDP to defense expenditure for the first time in 2015 (as did only three other European members of NATO – Estonia, Greece and the UK). In 2001 Poland passed a law committing the government to spend at least 1.95 percent of GDP on defense each year, and during 2015 the previous government modified this law, increasing defense spending to at least 2 percent of GDP. The new government has promised to consider raising this percentage further, having suggested during its pre-election campaign that Poland should spend as much as 2.5 percent of GDP on defense.

The Polish defense minister would also like to increase the size of the Polish army, starting with creating three new brigades for territorial defense on its eastern border. Prior to the election of the new government, Poland was already implementing an ambitious national military modernization plan, having committed itself to spending around USD 37 billion on military modernization by 2025. This money will be spent on upgrading armored and mechanized forces, anti-seaborne threat systems, new helicopters, air and anti-missile defense systems, submarines, and drones.

Outlook: convergence and divergence

In many respects there are increasingly common views among European governments on a number of security challenges. Practically all European governments care about the threats concerning terrorism, cyber-security, organized crime, the spread of weapons of mass destruction and state failure. And all agree in principle on the need to work together on developing costly military capabilities, with many investigating closer forms of military integration, not only cooperation with other countries.

But in some aspects there remain major differences among national defense policies, especially on geostrategic priorities. Only France and the UK retain a truly global outlook, although France is clearer that its priorities are Europe, Africa and the Middle East. Germany and Poland prioritize European security, especially the challenge of Russia, while Italy is more focused on North Africa and the Middle East. In a similar vein, only France and the UK, and to a lesser extent Germany, can simultaneously aim to perform a wide range of territorial defense and foreign intervention tasks. Other Europeans have to be choosier for a mix of geostrategic, political and budgetary reasons.

A Tale of Three Cities – Berlin, London and Paris

France, Germany and the UK collectively account for almost two thirds of EU defense spending, and just over 60 percent of defense expenditure by European NATO members. This means that their national defense policies have an enormous impact on European defense as a whole. There are a number of similarities in their approaches, alongside many clearly-identified shared interests. Each country is aiming to be as full-spectrum as possible, maintaining the ability to both adequately defend territory and deploy abroad.

Each of them has also promised to increase defense spending in the coming years, reflecting the difficult confluence of security crises that Europe faces today. All three have made important contributions to NATO’s reassurance measures to allies in Eastern Europe, such as participating in Baltic air policing. And all three have deployed forces to help fight ISIS and other Islamists in Africa and the Middle East, such as in Mali.

But there are some important differences between these three European heavyweights, too. Britain and France, for instance, are nuclear- armed powers and permanent members of the UN Security Council (UNSC), whereas Germany has no nuclear weapons (nor any intention of acquiring them) and is not a permanent UNSC member.

Britain and France are also much more experienced and more willing to carry out robust external military interventions, whereas Germany, up to now, has been more hesitant, preferring post-conflict peacekeeping and state- building efforts. France and Germany are relatively comfortable acting militarily through the EU, and support a stronger EU defense policy (alongside NATO) – although Berlin is more relaxed than Paris about sharing sovereignty on defense matters – whereas Britain strongly prefers to act militarily through NATO or other formats.

There are reasons to think that there may be some more convergence between Franco-British-German defense policies during 2016 and beyond. Following the terrorist attacks in Paris in November 2015, France stepped up its military operations against ISIS in Iraq and Syria, the UK joined in the bombing campaign in Syria (it already participated in Iraq), and Germany beefed up its support effort to the anti-ISIS coalition beyond sending weapons to the Kurdish Peshmerga, by sending a frigate and reconnaissance and tanker aircraft to support French bombing sorties. Additionally, all three will continue to contribute towards NATO’s defensive efforts in Eastern Europe. But there is potential for some divergences as well, for example between the UK and France-Germany on EU defense policy, or between Germany and Britain-France on burden-sharing in the Middle East and Africa.

Prioritization tests for the rest

Due to a mix of security priorities, lower levels of resources for defense and smaller size, Italy and Poland – and other European governments – face a different set of challenges to those of the ‘Big 3’. On the one hand, they are more dependent on cooperation with other countries, including through NATO and the EU. On the other, in comparison to the more powerful countries, they have to prioritize more narrowly where to direct their defense efforts, both geostrategically and operationally.

Many of these countries, like Italy and Poland, have produced new national security strategies or defense plans in recent years, and most are mainly concerned about instability in their immediate neighborhoods. However, there are some divergences in their geostrategic and operational priorities as well as their levels of defense spending.

For example, some like Italy are more focused on the Middle East and North Africa, others like Poland are focused on Russia and events in Ukraine. Similarly, a number are increasingly investing in territorial defense capabilities, while some others are more concerned about projecting force abroad. At the same time, strategic signals (even if only symbolic in some cases) such as Spain leading NATO’s Spearhead Force for deterring Russia (the VJTF) or Poland indicating a willingness to boost its military engagement in the Middle East, do offer encouragement for improving the overall coherence of European defense cooperation.

Capitalizing on convergences, managing divergences

The effectiveness of European defense cooperation will depend to a large extent on the ability of Britain, France and Germany to not only agree, but to also convince other European governments to support their approaches. Germany, as the largest and most powerful EU country, will play a pivotal role in coordinating European defense cooperation efforts, if it is able to “lead from the center” (to quote German Defense Minister von der Leyen). Germany shares much of the outlook and ambition of the UK and France, but with more constraints, which in turn gives Berlin a good understanding of the limits of other Europeans.

As much as the orthodox model of European defense cooperation – the institutionalized, top-down approach of the EU and NATO – has struggled, the current security crises and concomitant need for cooperation could contain the nucleus for future progress. The renationalization of European defense cooperation can lead to stronger European defense, including through the EU and NATO, if European governments capitalize on the convergences and manage the divergences of their disparate national defense policies. In turn, the EU and NATO should continue to help coordinate national policies and encourage cooperative projects, and treat the renationalization of European defense cooperation as an opportunity to reinvigorate their institutional efforts.