Power Politics in (Eur)Asia

23 Mar 2016

By Prem Mahadevan for Center for Security Studies (CSS)

This chapter of Strategic Trends 2016 can also be accessed here.

China is shaping its policy towards maritime disputes in Southeast Asia partly with a conviction that Western security efforts will remain concentrated against Russia. Its activities in the South China Sea resemble a maritime version of hybrid warfare. The US is keen to limit Chinese unilateralism by strengthening regional allies. However, Washington is also preparing to take a more prominent role in managing tensions.

Tensions between the United States and China are escalating. No longer is Washington a mere observer of maritime disputes in the South China Sea. Rather, it is a concerned actor. Recent Chinese actions indicate that Beijing wishes to unilaterally redraw political boundaries. The destabilizing factor is the appearance of seven artificial islands, constructed over the last three years, around which China is attempting to claim territorial waters. In effect, China is waging a maritime version of hybrid warfare, to impart political ballast to its anti-access/area denial (A2/AD) doctrine.

There is consistency on the part of both major powers. Beijing wants to limit the American naval presence in China’s so-called ‘near seas’. Washington wants continued access to these waters. Besides international law, what is at stake is the United States’ geostrategic advantage and the credibility of its alliance system, as reflected in its military relationships with Taiwan, Japan, South Korea and the Philippines. If China can contest the US Navy’s freedom to sail through the South China Sea, it would accomplish three objectives simultaneously. First, it would better protect its Sea Lines of Communication (SLOCs) to oilfields in the Persian Gulf and Africa. Second, it would gain partial control of the ‘first island chain’ that constrains its naval profile in the Indo-Pacific region. Third, it would crystallize doubts among American allies as to whether hedging against a rising China – which they are currently inclined to do – is a wise policy.

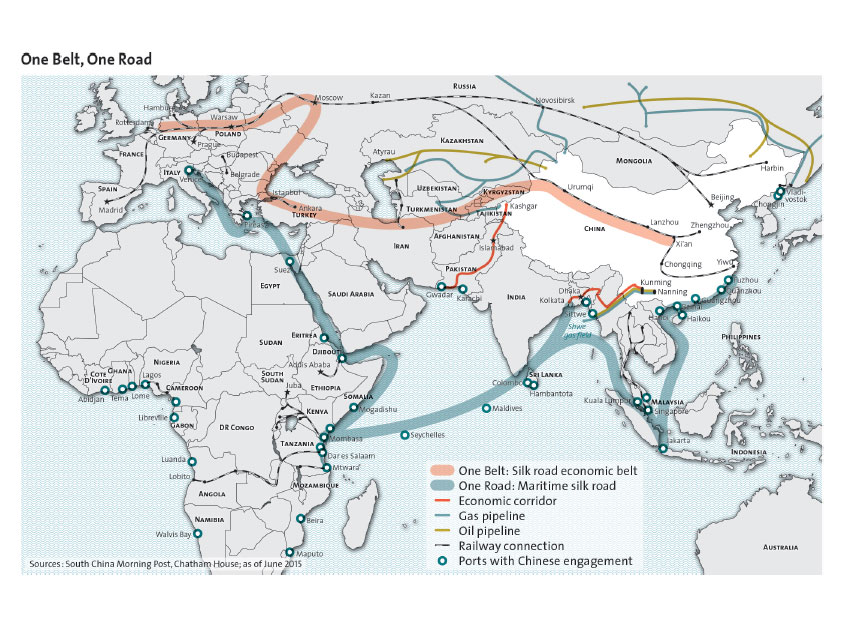

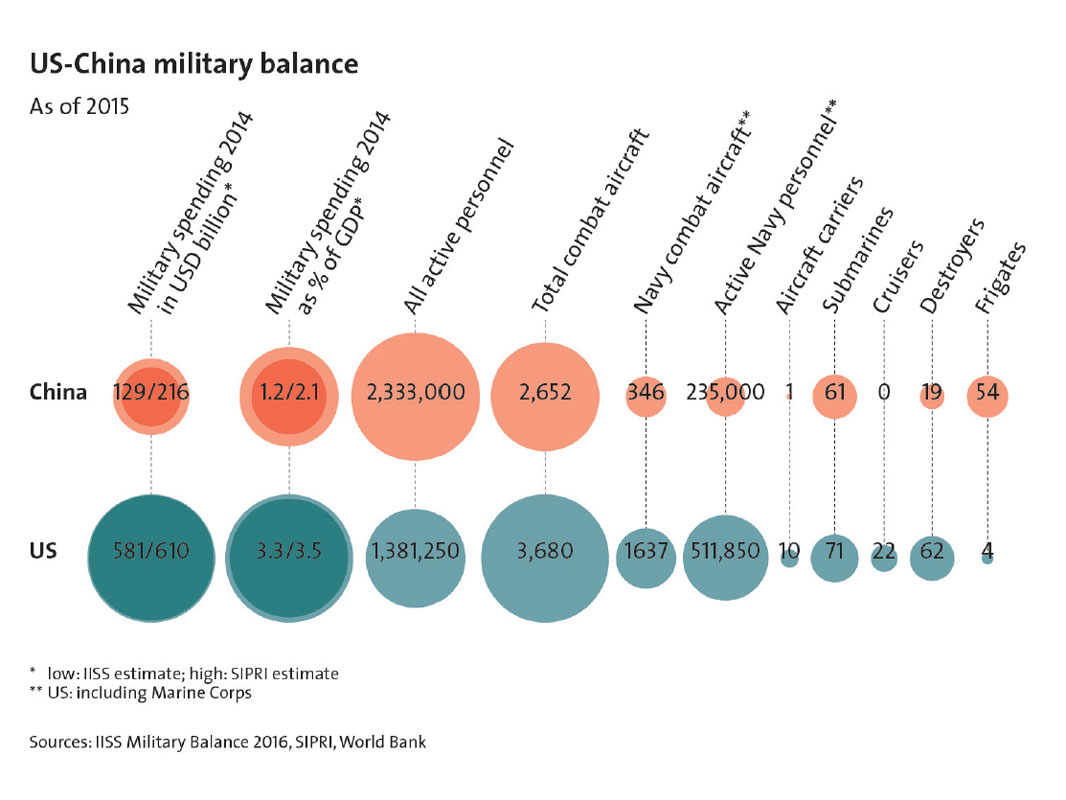

For its part, the United States faces a crisis of credibility vis-à-vis its regional allies. With Russian actions in Crimea and Eastern Ukraine having once more drawn the Pentagon’s attention towards Europe, and the ‘Islamic State’ posing a challenge to Middle Eastern stability, few Asian governments are banking on the longevity of the American military ‘rebalance’ towards Asia. They are aware of substantial cuts that American defense spending is likely to encounter over the next few years. The Obama administration is seen as risk-averse in matters of foreign policy, a belief strengthened by its failure to respond to the Syrian regime’s employment of chemical weapons. Meanwhile, Beijing seems poised to benefit from slowing-but-still-formidable economic growth that will bolster its claims to hegemony in Asia. High expectations are riding on its One Belt, One Road (OBOR) initiative, which could accomplish what Russia has long sought to do: drive a wedge between the United States and Europe.

The most salient feature of current Chinese foreign policy is the manner in which relations with the US are souring over maritime disputes in Asia, while those with some European Union members are blossoming. There is an inherent tension in how China approaches the broader Western community of states, which can be described as ‘geopolitics versus geo-economics’. However, differentiating between the medium and long term is necessary, as there is speculation that the ongoing slowdown in the Chinese economy would foster domestic instability in case China falls into the ‘middle income trap’ that plagues many developing countries. It is also uncertain whether the Chinese military can count on receiving double-digit budget increases every year, especially once competition for funding increases from the internal security agencies.

This chapter provides a pan-optic view of great power relations in Eurasia since 2014, before focusing on their local impact in the South and East China Seas. It will first outline how Russian actions in Eastern Europe have overshadowed similar Chinese tactics in East Asia, and driven Moscow into a state of quasi-dependency on Beijing that will work in the latter’s favor even as China bolsters its international standing without backing down on maximalist maritime claims. Thereafter, the chapter will turn to the claims themselves and elaborate on their present trajectory. Lastly, the chapter will discuss how the United States and its allies are preparing to deal with an anticipated increase in Chinese assertiveness.

Russia meets China, in Europe

In September 2013 Chinese President Xi Jinping announced plans to create a Silk Road Economic Belt that would connect China with Western Europe via Central Asia. High-speed passenger and freight railway lines would supplement Russia’s ageing trans-Siberian railway as the artery of overland trade in Eurasia. Closer to home, China would integrate its rail network with Southeast Asia by constructing new lines in Vietnam, Cambodia, Laos and Thailand. Accompanying this would be a parallel effort to strengthen maritime connectivity with members of the Association of South East Asian Nations (ASEAN). Initially announced in October 2013 as the Maritime Silk Road, the latter’s scope was expanded eleven months later to include the countries of South Asia.

The Ukrainian crisis of late 2013 and the subsequent Russian intervention in 2014 strengthened China’s negotiating position vis-à-vis its northern neighbor. Previously, Moscow had been either indifferent to, or suspicious of, Chinese keenness to conclude energy deals, seeing them only as a bargaining chip in Russia’s own negotiations with the European Union. However, once American and European sanctions were imposed in 2014, Russia courted China as a long-term business partner. Beijing leveraged this desperation to extract a generous gas deal, but the 2015 slowdown in the Chinese economy, together with sharp depreciation of the ruble, undercut the potential for increasing bilateral trade. Instead, China is now looking towards Central and Eastern European (CEE) countries to serve as its connector to the European Union, a role that these former communist states are eager to fulfill.

Even as the United States fulminated about Chinese intransigence in the South China Sea, many of its European allies were signing up to a Chinese-led project, the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank, which would fund the OBOR scheme. Having expected mainly to win support from governments in the global South, Beijing was pleasantly surprised by the eagerness of European Union members to join the bank in the hope of receiving economic favors. The alacrity with which the United Kingdom in particular, signed up to the AIIB and sought to position itself as China’s top lobbyist in the West was a disappointment for both the United States and Japan, and a diplomatic coup for China.

China seems to be using its economic heft to play a game of ‘divide and conquer’ against the Western alliance, and achieving a measure of success that has eluded Russia. Whatever trans-Atlantic consensus exists on Ukraine disappears when the issues at stake are the South China Sea and Chinese investment into sluggish European economies. Considering that China asserts ‘indisputable’ sovereignty over most of the Sea, despite this claim having no basis in current international law and being actively disputed by the Philippines and Vietnam, the comparison (and contrast) with Ukraine is pronounced. Beijing is backing its claim with shows of force on the water through coast guard patrols. It has commissioned the largest coast guard cutters in the world, whose size dwarfs even many American warships. Short of a shooting engagement, where the Americans’ superior firepower would be decisive, the cutters’ size allows for effective harassment of other countries’ ships inside Chinese-claimed waters.

With the consolidation of five maritime law enforcement agencies into a single force in 2013, China now possesses the largest coast guard fleet globally. It also has the world’s largest merchant and fishing fleets. Elements of the latter are travelling as far as the coast of West Africa and are engaging in large-scale fishing which is damaging to the economies of littoral states and maritime ecosystems. Their operations provide Beijing with plausible grounds to stand ready to ‘protect’ Chinese nationals far from home shores, even in waters that lie inside other countries’ exclusive economic zones. Meanwhile closer to home, the Chinese Navy is broadcasting to passing ships and aircraft in the vicinity of Chinese-claimed features in the Spratlys that these craft are intruding on sovereign territory and must leave immediately.

There are parallels between Chinese military settlements on artificial islands and the ‘little green men’ who appeared in Crimea during the spring of 2014, prompting the territory’s subsequent annexation to Russia. In both cases, the initial effort to alter the status quo was cloaked in defensive rhetoric that supposedly conformed to international norms. But there was a key difference: Whereas Russia denied that its forces were engaged on what was then Ukrainian territory, China did not disown its reclamation activities in the South China Sea. It did, however, mask its intentions, leaving the West to learn about the construction of military airstrips, harbors, radar and wireless installations through satellite imagery. A review of Chinese media coverage suggests that Beijing has taken a strong interest in how the West responds to territorial push-back from Russia. During the Russo-Georgian War of 2008, state-controlled reporting in China portrayed the conflict as a struggle for influence between a defensive Moscow and a rapacious United States seeking to bypass Russian dominance on Central Asian energy supplies by cultivating puppet states. Once the Ukrainian crisis erupted in 2013/14, Beijing was similarly quick to signal support for Moscow through its media. Apparently, on both occasions China calculated that the distant precedent of a nuclear power unilaterally imposing territorial changes through a combination of force and dissimulation would be useful for legitimating similar methods in its own backyard.

According to one assessment, the Chinese leadership has concluded that the Ukrainian crisis would give China an additional ten years to consolidate its claims in the South and East China Seas before any strong countermeasures are taken by the United States. Statements by top-ranking American officials that Russia constitutes the primary security threat to the US have pleased Beijing. It now hopes that Washington will have to split its attention between the Atlantic and Pacific naval theatres, as NATO members demand assurances of continued American commitment to their security.

The Sino-Russian dyad is a crucial influence on China’s behavior towards its Asian neighbors. Just as the diminished risk of land invasion from the Soviet Union emboldened Beijing to concentrate on building up its navy after 1985, so does the contemporaneous state of Russia-NATO relations shape its assessments of American pressure in the Indo-Pacific. Just as Russia has employed energy as a geopolitical instrument against the EU, so too does China dangle an economic carrot (and stick) to tempt European governments into dealing bilaterally with it, bypassing Brussels and ignoring Washington. Since 2007, it has used threats of closing off market access to deter international oil exploration in Vietnamese and Philippine waters. British Petroleum was the first major company to succumb to such pressure, a success which convinced China that the West would prioritize profit over principle, especially as the aftershocks of the 2008 economic crisis became evident. The OBOR initiative has now given China a mechanism for exporting its surplus industrial capacity (and incidentally, mitigating the effects of the economic slowdown) while buying influence overseas. By 2049, OBOR is expected to reach 65 countries, which presently account for 55 percent of global GDP, 70 percent of global population and 75 percent of proven energy reserves.

With its creation of the ‘16+1’ format to emphasize relations with former communist states in Europe, China is making substantial inroads into EU politics, much to the irritation of the Brussels bureaucracy. There are concerns that Beijing is playing off East-West differences between old and new EU members in order to gain political cover for its domestic human rights record and foreign policy in East Asia. But there are also reasons for Central and Eastern European states to be responsive to such overtures. Disappointed by the failure of EU accession to transform their economies swiftly enough, they are looking to China as a possible source of job generation. The statistics are both promising and suggestive: Trade between China and the 28-member bloc presently stands at 600 billion euros per year, and is expected to reach a trillion euros within five years. Fourteen EU member states are founding members of the AIIB, and the UK has agreed to Chinese investment in the construction of up to three nuclear power plants, a deal which would be unthinkable in the United States because of security concerns.

An important side-story is the interlinking of railway lines between Chinese and European cities. Since 2013, trains have been running partly on the infrastructure of the trans-Siberian line, introducing a rapid and inexpensive freight option to existing ones: air (fast but costly) and sea (slow but cheap). Although only 3.5 percent of China-EU trade occurs by land, despite the journey taking one-third the time as a sea voyage, this would change if China succeeds in coopting Central Asian states to host its expanding transport infrastructure. At the western end of the railway lines, the promise of fast connections to Beijing has Warsaw, Prague and Budapest jostling to be China’s preferred transit hub with the rest of Europe. The only major hurdle in this design would be a cooling of relations with Russia, which could occur if the EU eases sanctions on Moscow and allows the Kremlin to start reasserting Russia’s traditional dominance in Central Asia. Short of such an eventuality, the supporters of OBOR hope that it would become as crucial in shaping the geopolitics of the 21st century as the American Marshall Plan was to the 20th. Key to this process is the health of the Chinese economy, and whether Beijing would be able to export its domestic manufacturing surplus in the form of overseas contracts for infrastructure creation. To do so, it needs a steady supply of oil.

(Click to enlarge)

Mixing oil and water

As far as China is concerned, the South China Sea could constitute a ‘second Persian Gulf ’ and provide 30 years’ worth of hydrocarbons to fuel economic growth. Just where this estimate came from remains a mystery – Western experts believe that hydrocarbon reserves in the Sea are probably not as high as China expects and are likely to be found outside the waters claimed by Beijing. Even so, the intertwining of national sovereignty, energy security and bureaucratic self-interest has become so strong over the last two decades, ever since China became a net importer of petroleum products in 1993, that it has assumed a momentum of its own. At its leading edge is China’s infamous ‘nine dash line’.

The line dates back to 1936, a time when nationalist China was fearful of both Japanese and French expansion on its periphery and pre-emptively claimed 80 percent of the South China Sea as a buffer zone, along with 159 islands and islets. The line was a statement of intent rather than of fact, since China did not possess the naval capacity to enforce its claims to either the islands or the surrounding waters. In 1974, it carried out its first territorial seizure when it wrested the Crescent Group of the Paracel Islands from Vietnam, having already occupied the nearby Amphitrite Group unopposed. Beijing had picked its moment well: Knowing that South Vietnam was preoccupied with its civil war against the North, and that the United States was keen to balance against a revival of Soviet power in Southeast Asia following the anticipated North Vietnamese victory, it calculated the risk was minimal.

Between 1974 and the next outbreak of fighting in 1988, the international legal environment changed fundamentally. The 1982 United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) explicitly set a standard regarding the rights of coastal states. Islands capable of sustaining human habitation were entitled to 12 nautical miles of territorial waters plus 200 nautical miles of Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ), where the state which claimed physical possession of the island would have access to marine resources in the water and under the sea-bed. Rocks that lay above water at high tide received 12 nautical miles but no EEZ. Low-tide elevations which were mostly submerged received no privileges other than a 500-meter safety zone. Reclaimed islands built on low tide elevations (this includes all the islands recently constructed in the Spratlys by China) were only entitled to this same 500-meter safety zone.

Under these rules, which China ratified in 1996, the historical rights derived from Beijing’s adoption of the ‘nine-dash line’ would be overridden by a common set of norms that govern every UNCLOS signatory. Yet, China has persisted with its expansive claims, making them official in a map submitted to the United Nations Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf in 2009. Furthermore, it is interfering with the ability of marine traffic to come within close proximity of the seven artificial islands that it has constructed on low tide elevations in the Spratlys. While not explicitly claiming that the islands have generated new territorial waters or that the whole of the South China Sea within the nine dash line is China’s EEZ, Beijing repeatedly asserts that it has ‘indisputable sovereignty’ over the Sea. A major cause of concern for China’s neighbors and the United States is the combination of extent and vagueness inherent in this claim. Together with the growth of the Chinese shipping industry – ship construction has increased 13-fold in the last decade – Beijing can use the nine dash line to redraw international boundaries unilaterally. It had already seized Johnson Reef in 1988 after a battle with Vietnamese forces (another well-timed offensive, planned for a moment when Vietnam was diplomatically isolated) and in 1995, surreptitiously moved onto Mischief Reef near the Philippines.

The manner in which China occupied Mischief Reef raised the first suspicions about its long-term intentions in the South China Sea. Previously, its offensive actions had solely been directed at Vietnam. But when the Philippines, an American ally and ASEAN member, found that a body of water traditionally visited by its fishermen had been declared off-bounds by Chinese vessels and was the site of military construction, wider concerns were echoed. China’s response was almost identical to that associated with the term ‘hybrid warfare’ nowadays: Beijing at first denied any of its boats were near Mischief Reef. When confronted with photographic evidence, it changed its explanation to admit that maritime law enforcement agencies were in the area, but not Chinese naval vessels. Subsequently, it modified this story as well to acknowledge that the Navy had participated in the occupation, but claimed that this was the work of junior officials who acted without orders. Considering that a significant degree of logistical support for the Chinese occupation was manifest, this line of argumentation carried little credibility with the Philippine government or anyone else. However, without an act of overt aggression involving loss of life, as Vietnam had experienced, Manila could not count on American military support in its confrontation with China and had to reluctantly accept the new status quo. Beijing refused to discuss the matter in regional forums and bilaterally offered joint oil exploration – the likely trigger for the occupation itself had been the Philippines’ prospecting activity near the reef. Since this would have amounted to recognizing Chinese territorial claims in a part of the South China Sea which had long been free of disagreements, the Philippine government refused the offer.

A similar pattern of creeping encroachment is now evident in the waters around China’s artificial islands. No regional navy has the potential to withstand a confrontation with the Chinese Navy. Yet, accepting the new islands as entitled to territorial waters would not only flout UNCLOS, but would indirectly enhance China’s long-standing opposition to American surveillance of its shores. The issue here is that China believes that maritime intelligence collection cannot be carried out within its EEZ, although UNCLOS does not explicitly prohibit this. The US has been forthright about its desire to track Chinese naval deployment and force posture by over-flights and sailpasts from within the 200 nautical mile EEZ off the Chinese mainland. In 2001, a crisis arose after a US surveillance aircraft even collided with a Chinese fighter jet. If the newly reclaimed islands in the South China Sea are allowed to generate territorial waters, there would be little to stop Beijing from claiming an expanded EEZ around them by citing its ‘indisputable’ nine dash line. This EEZ could then be closed off to US naval vessels as the Chinese Navy grows more capable of long-distance operations and ventures into the Indian Ocean, ostensibly to guard the infrastructural investments that would accompany the Maritime Silk Road.

Although China denies that it intends to set up naval bases along the Indian Ocean rim, its sustained interest in gaining upstream control over energy supplies would necessarily draw its navy closer towards the Persian Gulf and Africa. There has been speculation that Beijing might set up as many as 18 bases, mostly in South Asia and along the east coast of Africa, to protect its SLOCs. The fact that China is building civilian ports in many countries along the oceanic rim has raised concerns about possible dual usage. The Chinese Navy would not need a large local footprint in order to operationalize an overseas base, if it already has Chinese state-owned companies waiting to receive its ships in harbor. Djibouti on the Horn of Africa has become significant in this regard: Already host to American, French and Japanese ships, it is likely to become the site of China’s first overseas naval base.

Timescales are crucial. No one is predicting anytime soon that China would physically interfere with American maritime surveillance, or establish naval bases far from its shores. But the shock generated by the rapid appearance of seven artificial islands in the Spratlys has made observers wary of absolutist predictions. Within a matter of two years, Beijing reclaimed 20 times as much land from the seabed as all other littoral states had over the previous four decades. It has constructed airstrips and harbors which could serve as forward deployment positions for naval aviation as well as surface and subsurface fleets. For instance, it is believed that China prioritized the reclamation of Fiery Cross Reef – which it first occupied in 1988 ostensibly for the purpose of scientific research – in order to build submarine pens there. With its Yalin naval base on Hainan Island located in shallow waters, subsurface assets of the Chinese South Sea Fleet were exposed to both peacetime observation and potential wartime strikes. Fiery Cross Reef is a possible alternate site due to the depths of its surrounding waters and proximity to the Straits of Malacca, a likely energy chokepoint that the US Navy would seek to exploit in the event of hostilities.

Sporadic rebalance

The US ‘pivot to Asia’ (subsequently branded as a ‘re-balance’ in order to convey greater durability) was partly triggered by China’s anti-satellite missile test in January 2007 and simultaneously by the impending American drawdown from the Middle East. At the time, relations with Russia were frigid but far from hostile, with the Russo-Georgian War yet to occur. This left Asia as the logical theater in which US combat forces would likely have to fight in the future.

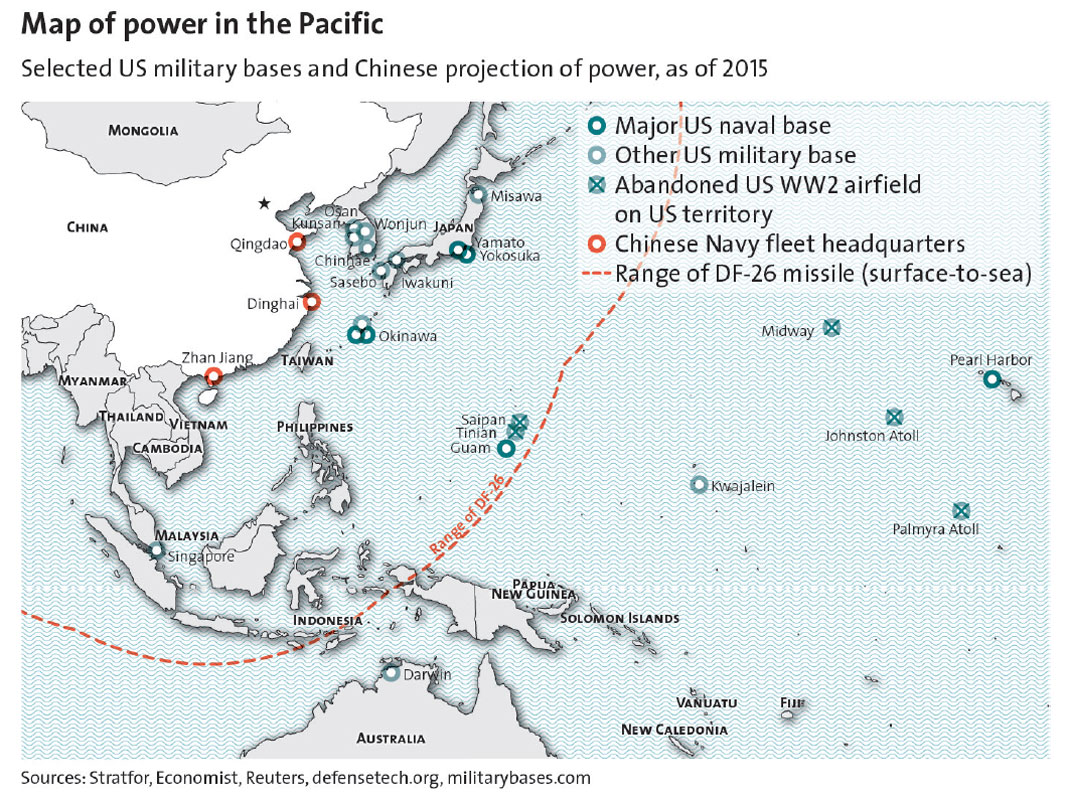

To maintain its dominance in the Pacific Ocean, the US Navy relies on two types of strategic assets: Satellites for communications and imagery intelligence, and on aircraft carriers. The Chinese missile test of 2007 and the development of anti-ship missiles, especially the DF-21D (dubbed the ‘carrier killer’) and its successor the DF-26, threatened both these asset categories. As the range of Chinese ballistic missiles increased, the infrastructure undergirding America’s war plans in the Pacific would be jeopardized and possibly made redundant. Anticipating this, from summer 2008 the US government began to assert that it had an abiding interest in Asia. China’s internationalization of its nine dash line in May 2009, when it made its submission to the UN Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf, gave Washington an advantage in its search for security partners.

The Asia Pivot/Rebalancing, at its core, aims to resurrect old alliances and establish new partnerships. The goal is to either steer Chinese behavior to conform to international norms or, if that fails, to contain the potential for aggression. Since the end of the Cold War, US basing arrangements in Asia have been political liabilities, stoking resentment among local populations in Japan and the Philippines. The rebalancing would avoid a heavy infrastructural footprint, instead relying on surge capacities to host US air and naval assets in the event of hostilities, while building up a stronger presence in American overseas territories in the Pacific. Considerable effort has been put into emphasizing the flexible nature of US basing agreements, both to assuage local politics and to keep the Chinese uncertain about how to orient their campaign planning. Forward deployments are considered necessary for the American naval force posture because average sailing time from the US west coast to East Asia would likely exceed ten days – too long for Washington to effectively intervene in a regional crisis.

There is general agreement among security experts that the South China Sea is only the outer layer of a larger security problem facing the US: guaranteeing the security of Taiwan and Japan. Since 1996, the Chinese Navy has planned for a Taiwan-related confrontation with its American counterpart, using asymmetric tactics and technologies. China’s anti-access/ area denial concept builds on ideas developed by the Soviet Union during the Cold War. The intention is to keep the US Navy as far from Chinese shores as possible by relying on submarines and land-based airpower and missilery. For its part, the US has developed its own doctrine to hit the Chinese mainland in the event of an onshore threat to the Pacific Fleet. Known initially as Air-Sea Battle, it has now been rechristened ‘Joint Concept for Access and Maneuver in the Global Commons’ (JAM-GC).

(Click to enlarge)

The new Chinese-occupied islands in the South China Sea are not a serious military obstacle to the US Navy – any threat they pose could be eliminated through ship-launched missiles. However, they serve as a diversion that will consume at least some of the ordnance which would otherwise be used in a Taiwan contingency. Vertical Launch Systems (VLS) onboard American surface and subsurface vessels cannot be reloaded at sea. Once fired, they remain empty until the vessel calls at a friendly port. By increasing the sortie range of its land-based airpower and missile shield, China hopes that in a war involving Taiwan the US Navy will have to expend a larger percentage of its munitions merely protecting its assets than interfering with amphibious landings by Chinese ground forces.

On the other hand, China cannot expect an easy takeover of Taiwan as long as US security guarantees to the island remain in place. Beijing has warned that any political steps towards the assertion of Taiwanese independence, or even inordinate delays about reunification with the mainland, could constitute a casus belli. With the victory of the independence-inclined Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) in the January 2016 Taiwanese general election, cross-strait relations are likely to become chilly. A formal declaration of independence seems most unlikely in the foreseeable future, but anti-mainland sentiment has been mounting for some years in Taiwan and the DPP’s electoral success reflects this.

Taiwan has little capacity to resist an invasion for long; at most, its small armed forces can only stall a Chinese invading force long enough for the United States to intervene militarily. This is where the doctrinal race between A2/AD and JAM-GC becomes crucial. Although the Chinese Navy is larger than its American counterpart in terms of hull numbers, its ships are at least two technological generations behind. Beijing is trying to make good on this deficiency by spending on capability upgradation: Between 2004 and 2011, the percentage of modern units in its surface fleet increased from 10 to 30 percent while the corresponding change in the submarine fleet was from 10 to 50 percent. The US can offset the enhanced threat to its Pacific fleet by reactivating old naval and airbases in South-east Asia (which it has already begun to do in the Philippines) and forward airfields in the Pacific.

The standoff regarding China’s newly reclaimed islands is thus a sideshow to the bigger question of whether the US Navy will continue to have unrestricted rights to sail through East Asian waters, several years into the future. Few Asian countries are willing to bet completely on this. Japan in particular feels vulnerable due to its long-standing dispute with China over the Senkaku/Diaoyu Islands in the East China Sea. Like the Spratlys and Paracels, the real issue is not the status of the islands themselves, but the possibility that the surrounding seabed is rich in hydrocarbons. China’s interest in the Senkakus/Diaoyus was prompted by a 1968 – 69 survey which suggested oil and gas finds in the area. For many years, the weak state of the Chinese Navy (traditionally the lowest priority for military spending among the armed forces) precluded any assertion of Beijing’s claim. The islands therefore remained under Japanese administration. Starting in 1999, Chinese naval vessels began to conduct maneuvers in their vicinity. Since 2008, Chinese ships have routinely breached the 12 nautical mile territorial seas that possession of the islands gives Japan. Fighter aircraft have conducted over-flights with increasing frequency, to patrol an air defense identification zone (ADIZ) that overlaps with Japan’s, prompting Japanese fighters to scramble in response. Japan has accused China of reneging on an agreement to jointly develop hydrocarbon resources in the East China Sea, by building gas platforms near the equidistance line between the two countries (which have not yet agreed on EEZ delimitation).

In September 2015 Japan passed legislation to permit the overseas deployment of forces in support of allies (read: US). This move was criticized domestically but viewed as a necessary step towards tying the US closer to Japan’s security. Washington has asserted that although it takes no position on sovereignty issues, the Senkakus/ Diaoyus are covered by the mutual security treaty of 1960, which means that a Chinese attack might provoke an American response. Tokyo feels that it must take a firm stand on the islands, having already lost the southern Kuriles to Russia and the Dokdo/ Takeshima islands to South Korea following its defeat in World War II. Japan is as dependent on energy imports as China and the prospect of oil and gas fields in the Senkakus is sufficiently attractive for the Japanese government to remain firm on retaining them. Accordingly, it has begun efforts to raise a marine assault capability and expand its Maritime Self-Defense Force (already one of the most sophisticated navies worldwide) by acquiring more submarines and aircraft. However, it is unclear whether even this enhanced posture would succeed in repelling a Chinese occupation of the islands after a 10 – 15 year timeframe, as China continues to expand and modernize its navy. The alliance with Washington is thus crucial. With Sino-Japanese relations being clouded by historical animosity dating back over a century, the island dispute in the East China Sea is more publicly emotive than those in the South China Sea.

The US, for its part, is encouraging its allies and partners to cooperate more with one another, as part of a burden-sharing process that would both deter China from attacking any single disputant and facilitate a common response if hostilities erupt. Thus, it is tacitly approving Japanese efforts to boost the patrolling capacity of the Vietnamese and Philippine coast guards through donating ships. Joint exercises with these countries, as well as India and Australia, are becoming more common. To challenge Beijing’s effort at claiming territorial waters around its artificial islands in the South China Sea, Washington has authorized freedom of navigation operations (FO-NOPS) which assert the right of US ships to sail anywhere outside internationally recognized territorial waters. The first FONOP, conducted in October 2015, was shadowed by an American carrier group, just in case the Chinese response would be escalatory. Although China strongly criticized the maneuver, it avoided direct confrontation. This would almost certainly not be the case if Japan were to carry out its own FONOP in the Spratlys, as occasionally suggested in media reports. Chinese pressure therefore acts as a brake on how far US allies can go in antagonizing Beijing, as long as overt hostilities do not break out.

To some extent, China is testing American resolve already. Nearly two months before the US FONOP in the South China Sea, five Chinese naval vessels sailed close to the US-administered Aleutian Islands in the Pacific. Whether this was intended for domestic consumption, to suggest to an indignant Chinese public that the forthcoming American move was only a ‘response’, is unclear. Some analysts speculate that China might in fact have hoped for American push-back in the Spratlys, which would give it an excuse to further strengthen its military footprint on the islands. What is clear though is that Beijing is not afraid of challenging the US on the finer points of international law. While it objects to military craft entering its own EEZ, since 2013 it has been sending Chinese Navy vessels (including Type 815 spy ships) into the American EEZ around Guam and Hawaii. It has also exercised the ‘right of innocent passage’ inside US territorial waters. Thus, at a perceptual level, China is prepared to match the United States, move by move, in a slow-paced contest for legitimacy and naval presence across the Pacific.

Expectation (or superstition?) of change

Military reforms announced by Beijing in September 2015 point to the future: Chinese ground forces will be downsized and more funds freed up for the Navy and Air Force. China is counting on Russia’s economic dependency to scale down the size of its army and devote greater attention to the likely theater of conflict: the ‘near seas’. Chinese President Xi Jinping has proven uncompromising on maritime disputes – the first US FONOP took place shortly after a meeting with US President Barack Obama, during which no understanding could be reached regarding artificial islands in the Spratlys. Xi has associated himself closely with the military reforms and is likely to compensate for their unpopularity with the army by taking a firm stance on issues that interest the other services. He would have the weight of public opinion behind him: With Chinese expatriates coming under threat from terrorist groups and political rebellions abroad, the government has been looking to strengthen its expeditionary warfare capability. The 15,000 strong marine force, which is under the command of the Navy’s South Sea Fleet, has lately been training for desert operations – a sign that China is not going to let itself be confined to the Pacific rim. The likelihood that Chinese and American ships will shadow each other on the high seas while on training and humanitarian missions seems strong. However, this need not necessarily lead to an escalation of tensions, unless China makes further efforts to enforce its nine dash line. In the event that it does so, China’s enhanced capability for force projection would ensure that the US Navy and those of American allies would have a formidable, but still manageable, opponent to confront.

(Click to enlarge)

With a US presidential election looming in 2016, there is a belief that coming months will see major changes in the Sino-American geopolitical contest. One forecast holds that Beijing may want to trigger a limited-scale crisis with Japan over the Senkakus/ Diaoyus, as a way of humbling Tokyo and demonstrating Chinese power while the US is preoccupied with domestic politics. Another scenario could be one of growing tensions between China and Vietnam, especially as China recently moved an oil exploration rig into Vietnamese-claimed waters in the South China Sea. Unlike an earlier crisis in summer 2014, this time China has been less overtly provocative in its placement of the rig, which raises concerns about whether it intends to keep the rig in place despite Vietnamese protests. Its economic slowdown is unlikely to induce the Chinese government to scale back maritime claims; it may provide an incentive for Beijing to seek an overseas distraction from domestic troubles.

China will have noted with satisfaction that the US in February 2016 announced a build-up of conventional forces in Eastern Europe, designed to deter Russian adventurism. It continues hoping that Washington’s attention will remain divided between slow-burning tensions in Europe and Asia, and a fight against the so-called ‘Islamic State’. Meanwhile, the Sino-Russian relationship will be crucial to the realization of China’s OBOR scheme. And, even as it pushes west-ward over land, China is likely to enhance its naval presence around the Indian Ocean rim according to the One Road plan. Whether this will serve to protect its SLOCs or to widen the theater of naval competition with the US, potentially drawing in other regional powers such as India, remains to be seen. In any case, a drastic escalation of tensions is unlikely but shows of force – partly designed to mirror those conducted by the US – are more likely to occur than in the past.