Global Disaster Politics Post Sendai

18 Apr 2016

By Tim Prior, Florian Roth for Center for Security Studies (CSS)

This article was originally published as CSS Analyses in Security Policy, No. 173 by the Center for Security Studies (CSS). It is also available in German and French.

As the global costs of disasters continue to rise, a new global framework for disaster risk reduction was negotiated at a high-level conference in Sendai, Japan in March 2015. Newfound global attention to the topic increased the difficulty of negotiations, but also created opportunities, especially for Switzerland as an active leader in disaster risk reduction in international development.

Floods, earthquakes, wildfires, and tropical storms are all examples of recurring natural hazards, but they are only classified as disasters when lives or property are lost. While there is debate about whether the frequency of natural disasters is increasing, growing populations and continued urbanization (especially in developing countries) are placing more people and property at risk of the consequences of natural hazards; the recent earthquake in Nepal being a catastrophic example of this. Disaster Risk Reduction (DRR) is the practice of reducing this hazard exposure and sensitivity.

From 14 – 18 March 2015, the international community gathered in Sendai, Japan, for the Third World Conference on Disaster Risk Reduction. The purpose was to negotiate a global framework to guide disaster risk reduction until 2030. Conference participants were galvanized to reach this goal by memories of the 2011 East Japan earthquake, the resulting tsunami, and the Fukushima nuclear melt-down on the one hand; and on the other hand, by the prospect of leveraging the new global framework for DRR off a synchronization of post-2015 global agendas in development cooperation, environmental sustainability and climate change, sustainable development, and humanitarian aid.

The Sendai conference aimed to produce a successor agreement to the Hyogo Frame work for Action (HFA), negotiated soon after the catastrophic Indian Ocean Earthquake and Tsunami (2004). While legally non-binding, the HFA (2005) brought the topic of DRR to new prominence, triggering important advances in domestic risk management and international cooperation. Prior to the new agreement being negotiated in Sendai, many observers held high expectations that the post-HFA agreement would bring a new level of international commitment to DRR, including concrete goals and actions.

In the end, however, the conference in Sendai yielded mixed results. On the positive side, the new Sendai Framework Agreement (SFA) highlights the key importance of preparedness and preventive actions for reducing vulnerability to disasters and for building resilience. Further, the SFA provides several global targets to guide DRR for the next 15 years. However, overly politicized negotiations curtailed the inclusion of ambitious and concrete indicators that could track the new framework’s progress toward its goals, and prevented the inclusion of institutional mechanisms to monitor the implementation of the agreement. Ultimately, the SFA is an aspirational framework that must be filled with life and purpose through effective implementation, meaningful investment, and political will.

The Road to Sendai 2015

The road to Sendai began in 1989. Until then, international cooperation and coordination in the context of DRR was mostly restricted to humanitarian aid during the response phase of disasters, and few global mechanisms to coordinate disaster risk reduction existed. By 1989, the broad notion of “global security” was extending beyond military threats and conflicts to include environmental, industrial, and technological problems, and the political climate became increasingly amenable to global governance approaches. This change was triggered by the end of the Cold War, and by the recognition that the rising costs of natural and technical disasters were unsustainable. In response the United Nations declared the 1990s the “International Decade for Natural Disaster Reduction”.

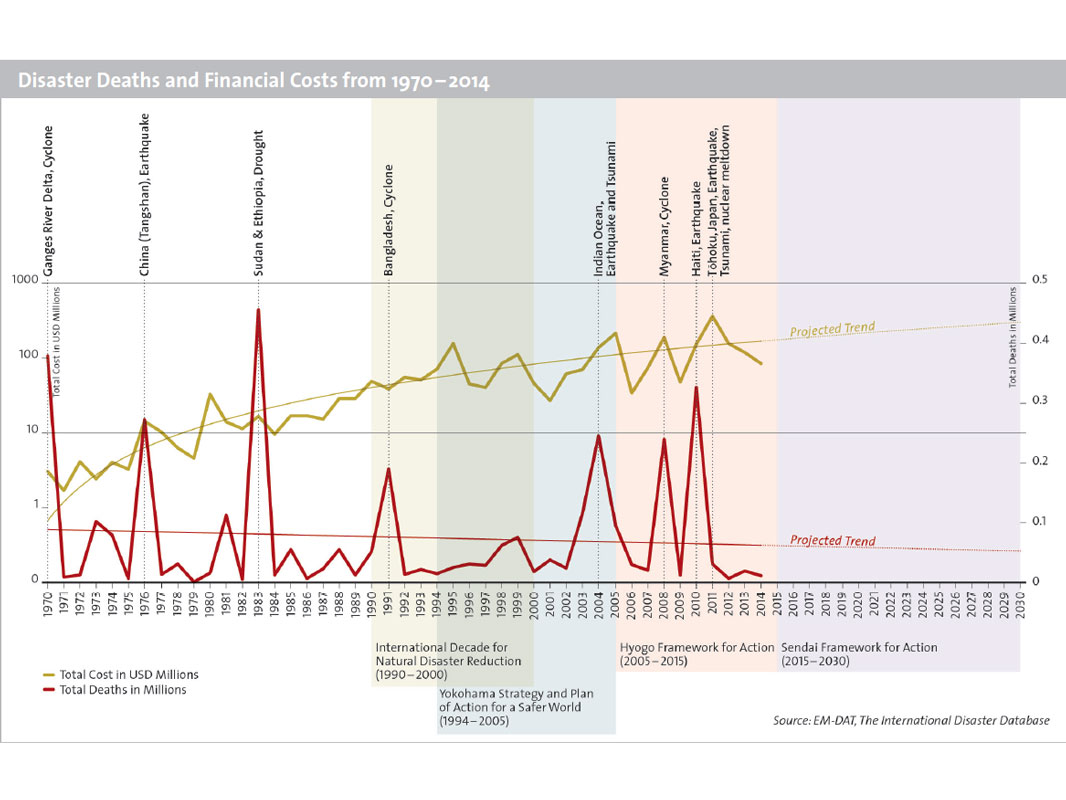

A major milestone of the “Decade” was the successful negotiation of the Yokohama Strategy in 1994, the result of the first UN World Conference on DRR. It shifted the focus of international disaster management efforts from response to prevention, mitigation, and preparedness. However, as a non-binding strategy, it provided little more than a common denominator for more investment in DRR actions. Since it did not outline any concrete DRR process, levels of disaster preparedness remained low, DRR actions remained ad-hoc, and disaster losses from natural and technical hazards did not decline (see graphic).

More than a decade after the Yokohama Strategy was agreed, the second UN World Conference on DRR took place in Kobe, Japan, in 2005. The conference opened just weeks after the Indian Ocean tsunami had killed 230’000 people. With little fuss, a total of 168 nations signed the conference agreement to “build the resilience of communities and nations to disasters”: the so-called Hyogo Framework for Action (HFA). The HFA was the most comprehensive and ambitious attempt to put DRR at the top of the international political agenda. It focused on prioritizing the institutional bases of national DRR programs, especially through effective early warning, and by seeking to address underlying social risk factors connected to human development and inequality.

Post-Hyogo: High Expectations

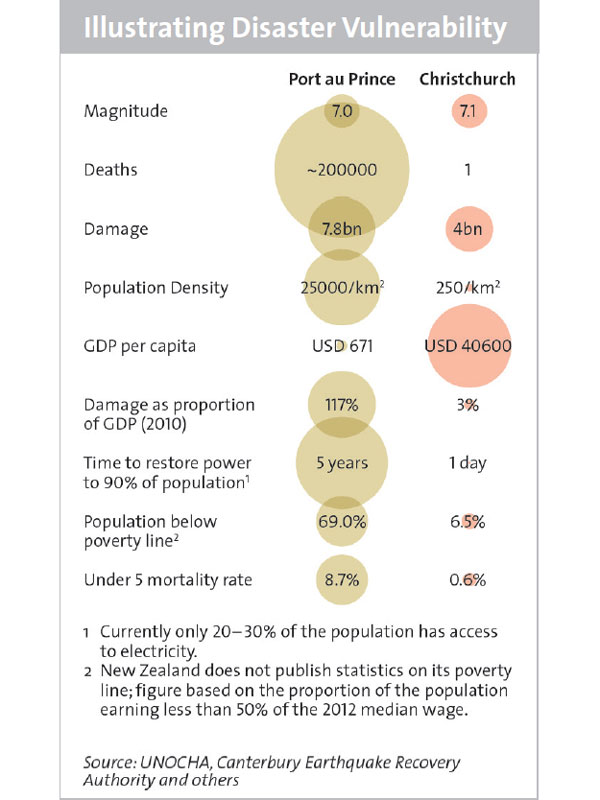

From 2005 to 2015, the HFA encouraged considerable progress in global risk governance. In particular, the agreement gave DRR unprecedented political prominence by creating normative pressure on national governments to align domestic civil protection systems with global priorities (in systematic risk analyses and monitoring procedures, for instance). However, political realities also revealed at least three major limitations of the HFA. Firstly, sub-national and local-level disaster management received marginal attention in the HFA, although these are crucial elements in many national civil protection systems, meaning the HFA was often disconnected from disaster management practices on the ground. Secondly, the HFA’s strong focus on natural hazards inevitably neglected man-made risks, such as terrorism or industrial accidents, and diverted attention from efforts to address the underlying social vulnerabilities that typically worsen disasters (see comparative illustration). Thirdly, the HFA failed to translate policy priorities into concrete and assessable measures, specifically lacking an institutional mechanism (similar to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, for example) to assess the framework’s progress. Instead, the framework relied on annual self-assessments by the signatory countries, resulting largely in a reframing of existing practices in the language of the HFA without inducing real policy shifts that could reduce hazard vulnerability and increase resilience.

In the run-up to Sendai, many observers were optimistic that a new framework could overcome some of the HFA’s recognized weaknesses. For one thing, recent disaster events, including the Ebola and N1H1 pandemics and the 2011 Great East Japan earthquake-tsunami-nuclear catastrophe, re-emphasized the urgent need to align global DRR governance mechanisms. Additionally, the timing of the Sendai conference, as the first in a series of interdependent global processes, was seen as an opportunity to integrate DRR seamlessly with climate change, sustainable development, and humanitarian aid agendas to better address underlying hazard vulnerabilities. A strong framework from Sendai could set the course for a future characterized by a synchronized and comprehensive approach to reducing global disaster risk.

Switzerland was an active player in the political run-up to the Sendai Conference and the new strategy. For instance, the Swiss government has provided expert and diplomatic support to the UNISDR, particularly for the two main preparatory committee meetings where the preliminary agreement was drafted. One of Switzerland’s priorities was to secure recognition that the connection between armed conflict and weak governance could complicate DRR efforts, a topic that had emerged during Switzerland’s Chairmanship-in-Office of the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE) in 2014. Making states resilient to disaster and climate risks had been one of the priorities of the Swiss OSCE diplomacy during its presidency. Throughout the political process leading to Sendai, Switzerland has been able to build on its reputation as a country with high standards in civil protection, helping it to influence the drafting process in preparation of the Sendai conference.

The Bubble of Hope Bursts?

As negotiations for the post-HFA framework progressed in Sendai from 14 – 18 March 2015, delegates from 187 states soon recognized that their job would be much tougher than they had expected. Key points of disagreement were contested between several developing countries (mainly organized under the G77 umbrella) and developed nations, particularly the Western Europe and Others Group (WEOG, including Canada, Australia, New Zealand, and the US as observer). While the G77 sought a far-reaching agreement in which developed countries would directly support developing countries in reducing disaster vulnerabilities, the WEOG was eager to avoid any commitment in this direction, particularly in the contexts of the upcoming conference on development financing in Addis Ababa.

Negotiations also stalled around the question of technology transfer between developed and developing nations for improved DRR, and how compensation should be connected to such technology transfers to guarantee intellectual property rights. With countries unwilling to compromise on their positions, conference participants briefly contemplated the possibility that these political controversies might prevent the resolution of an agreement. However, in true Hollywood style, delegations managed to agree on the so-called Sendai Framework Agreement (SFA) at the last minute on 18 March 2015, satisfying some, but frustrating others.

In three respects particularly, the SFA represents a significant improvement compared to its predecessor. Firstly, compared to the HFA, a better understanding of resilience thinking strengthens its application in DRR strategy-making in the SFA. The SFA highlights that any limitation on global cooperation in international disaster relief is unacceptable, and places even stronger focus on measures of prevention and preparedness. Secondly, the SFA more comprehensively considers issues like public health, the role of women in DRR, and the need for local-level actions, all known to strongly influence vulnerability. Thirdly, the SFA includes a set of substantive commitments to be reached by 2030: reducing the number of people killed or otherwise affected by disasters; lowering damage to critical infrastructures; and scaling up international partnerships that support developing countries’ DRR efforts.

Notwithstanding these advances, many participants left Sendai with a feeling of disillusionment. In particular, if measured against the Yokohama Strategy and HFA, the new agreement could hardly be considered a giant leap forward for global DRR governance, as several key aspects were left untouched. For instance, the link between conflict and disaster, which had been incorporated in early drafts and was a key position for the Swiss delegation in Sendai, was ultimately removed in the SFA. Further, many observers and negotiators alike were visibly frustrated by the removal of concrete numerical targets from pre-conference drafts of the agreement, which would have simplified future objective assessment of the SFA. Moreover, the SFA failed to create a stronger institutional basis to guide the implementation and monitoring process. For instance, suggestions to upgrade the UN Office of Disaster Risk Reduction (UNISDR) from a ‘strategy’ to a ‘program’ in the UN system, and provide it with additional funds, were disregarded during the negotiations. This particular outcome bears a certain bitter irony: many observers believed that the weak leadership of the UNISDR was to blame both for insufficient preparation prior to the conference and for its unsatisfying outcome, and may therefore have been unwilling to provide it with a stronger mandate giving it the capacity to overcome exactly these barriers. Finally, the conference achieved little that would directly mitigate the vulnerabilities of the people living in underdeveloped countries, who are most exposed to disasters. In particular, commitments to financial obligations for DRR were excluded from the agreement in light of the upcoming development and climate change talks.

So, contrary to the expectations of many, the timing of the Sendai conference actually became an obstacle that complicated the negotiations.

The Way Forward

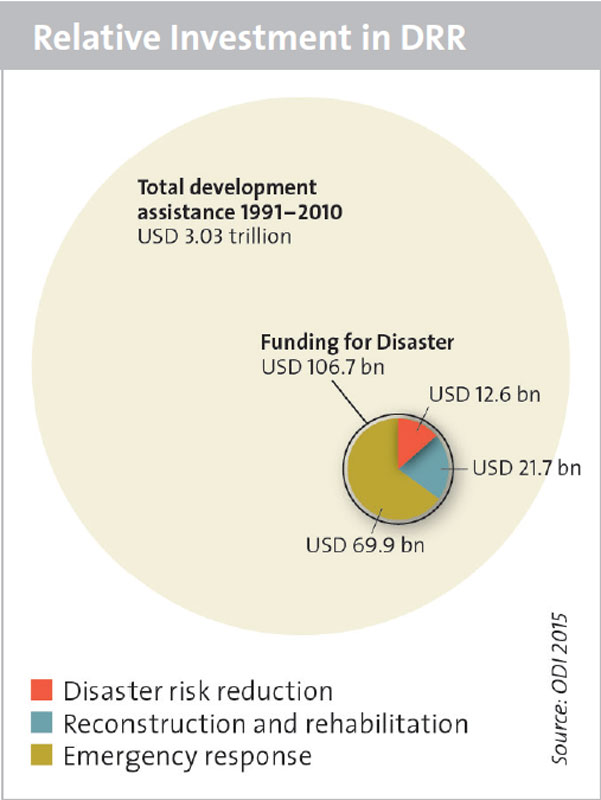

In spite of the somewhat sobering experiences of Sendai, the politicization of the SFA negotiations should not be viewed as overly negative for the new framework. In fact, the fraught negotiations have actually raised the profile and political relevance of DRR in the contexts of sustainable development, climate change, and humanitarian aid. Imbuing these key political processes with the imperative of disaster resilience could ultimately prove to be at least as important for advancing DRR over the next 15 years as the SFA. Particularly in the context of development policy, DRR has received only very marginal attention: Only about three per cent of international development assistance has been invested in disaster management. From this slim stake, about twelve per cent has been allocated to preparedness and prevention measures, with the vast majority dedicated to emergency response and reconstruction efforts (cf. graphic). This spending pattern is illustrative of an historic and systemic lack of political will and financial support for DRR in international development. However, proponents of stronger international cooperation for DRR can use this new political climate to bring about transformative change in this important security domain.

For instance, although the link between DRR and conflict was overlooked in the SFA, DRR’s new political currency provides a chance to address this issue. Here, Switzerland can lead by doing – by developing competence in understanding the relationship between conflict and DRR, and by incorporating this knowledge into better development and humanitarian aid practices. Switzerland enjoys a respected position in DRR discourses, which should serve as an opportunity to take an even stronger political leadership role under the SFA regime.

While the SFA may have missed some opportunities, global disaster risk governance post-Sendai is by no means dead. After all, the SFA remains the central strategy guiding trans-border coordination and cooperation in DRR, offering valuable opportunities to enhance existing policies and practices. Two main complementary points will be central in this respect. First, states must reinforce their efforts to advance national disaster management systems, especially by improving coordination between sub-national and local actors, which remains a weak spot in the civil protection systems of both developed and developing nations. Second, the task of building social resilience cannot be left to specialized civil protection agencies, but must be integrated into all related policy fields. For instance, disaster risk management issues are often neglected in urban planning, and this pattern must not continue. At the very least, the SFA should be viewed as a guiding document that can be filled with life to give it real-world relevance. It is up to the signatory states to take the agreed priorities and mechanisms seriously, to capitalize on newfound political momentum, and to use this momentum to address vulnerabilities and truly reduce the disastrous consequences of natural and other hazards.

.jpg)