Promoting Salafi Political Participation

5 May 2016

By Jean-Nicholas Bitter, Owen Frazer for Center for Security Studies (CSS)

This paper was originally published by the Center for Security Studies (CSS) in April 2016.

For many observers, Salafism is a rather nebulous movement generally associated with a conservative strain of Islam and with jihadi violence and terrorism. As a result, it has been ostracized and treated indiscriminately as a problem, particularly by those concerned with countering terrorism and preventing violent extremism. But, Salafism is not a homogenous movement. This paper presents a simple typology of trends within Salafism to highlight that important opportunities exist for engaging with Salafi groups to promote democracy and prevent violence.

Salafism explained

Salafism is concerned with promoting a pure form of Sunni Islam as it was practiced by the first three generations of Muslims referred to as as-Salaf as Sālih (the righteous predecessors). It first emerged in the 9th century CE and is based on the belief, that many non-Islamic innovations and practices have entered the religion and there is a need to return to the original teachings and practices. It therefore places a strong emphasis on the primacy of the central texts of Islam and their interpretation.

A number of typologies have been proposed which distinguish between different tendencies and groupings within Salafism. A very simple typology, which picks out four general trends, can be helpful for those interested in democracy promotion and the prevention of violence. [1]

The “quietest” tendency in Salafism eschews any participation in politics and is focused on preaching and promoting Islam. The “Jammi/Madkhali” limit their engagement in politics to supporting existing authoritarian regimes claiming to be Islamic, as found for example in Saudi Arabia. They believe that loyalty is owed to regimes that impose themselves and show strong authority (the principle of ghalaba), regardless of their politics.[2] The “jihadi” groups are committed to the use of violence to bring about their revolutionary political goals, notably the establishment of an Islamic state. Finally, the participative “Haraki” groups are committed to achieving their political aims through participation in democratic politics. It is the recent growth of this tendency that is of particular significance.

Salafism and the “Arab Spring”

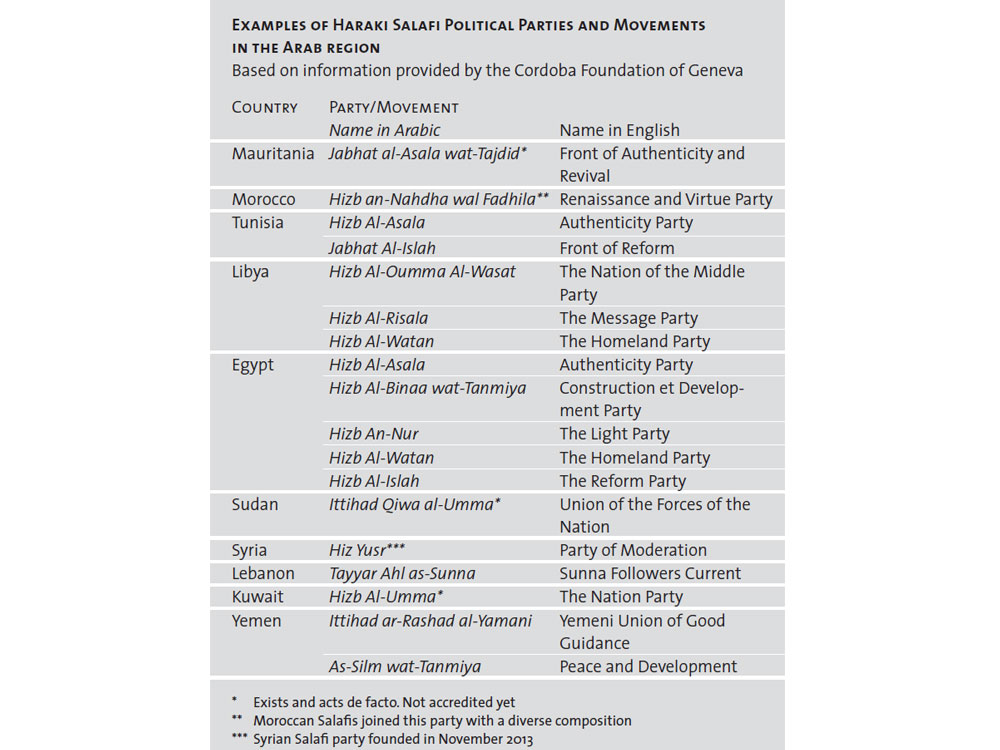

Before 2011, most Salafi groups believed that there was no space for them to pursue their agenda through politics. [3] Beginning with the revolution in Egypt in 2011, a number of new Salafi political parties emerged in order to participate in the democratic transformations that were taking place from Yemen to Mauritania and to prevent a return to authoritarianism. These groups accepted that they would need to cooperate with other political actors and to work within a pluralist political space. (See info box for a list of such groups).

While subsequent events in Egypt, Syria, Yemen and elsewhere have tempered the enthusiasm and optimism of many who had hoped that 2011 marked a turning point for politics in the region, the growth in the number of Haraki Salafi political groups does represent a lasting change in the political landscape.

Salafi political participation

The formation of Salafi political parties, and their declared willingness to abide by democratic principles, is significant because it offers those supportive of Salafi views a legitimate means through which to try and influence how society is governed.

For Salafis (or anyone for that matter) to feel that they have a reasonable chance of democratic influence, two basic conditions must be met. Firstly, political parties who represent their viewpoint must be capable of actively participating in politics. Secondly, democratic politics must be perceived to be at least partially functioning.

This second condition is clearly not always met. In Egypt, for example, the return of the military to power, and the clamp-down on democratic freedoms, has led many political activists to the conclusion that the scope for influencing government through participation in party politics is severely limited. Nevertheless, there are a number of contexts such as Kuwait, Mali, Mauritania, Morocco and Niger, where the political space remains more open for all political actors, including Salafi groups.

In such countries there are two main kinds of obstacles that new groups entering into politics face: their own relative ignorance and inexperience of how democratic politics works, and prejudicial and exclusionary attitudes of other political groupings.

Examples of Haraki Salafi Political Parties and Movements in the Arab Region (click to enlarge).

Strengthening political know-how

Lack of political know-how and experience can be addressed by providing capacity-building on how to engage in politics: the rules of the game, how to negotiate, how to build coalitions with different groups, how to communicate a clear governance program, etc. This can take the form of trainings and forums for exchange with experienced political actors. Salafi parties are often particularly concerned with how to negotiate their acceptance within the political sphere, without de-legitimizing themselves in the eyes of their followers. Here they may be interested to learn from the experiences of other religiously-inspired political movements.[4]

This support must be offered in a way which avoids favoring one particular political viewpoint. It is therefore advisable that opportunities are offered not only to Salafi political actors, but to a wide range of political actors. When appropriate and feasible, these can take the form of joint events where a diversity of political actors have the chance to come together and know each other better. This will also help address the second obstacle to Salafi political participation: the attitudes of others.

Overcoming suspicion and distrust

Many political actors are suspicious of Salafi groups. This can translate into an unwillingness to engage with them, or even into policies which actively exclude them. Such obstacles can best be overcome by finding ways to promote contact and dialogue. One way to do this is to initiate dialogue around a common goal or idea to which all would like to practically contribute. The room for misunderstanding between political groupings with radically different reference points and philosophies is very large. Working together practically on an issue of common concern helps to build understanding as each is able to relate the others’ statements and proposed actions to something concrete. For example, we were inspired to see how in Egypt a few years ago it was possible to bring together a wide range of political and civil society actors, including a number of Salafi groups, to discuss and work together on preventing Muslim-Christian violence. This common interest enabled the creation of a space where actors of different political persuasions could work together without having to specifically address their political differences, while at the same time getting to know and understand each other better. Many more areas of co-operation can be imagined, such as in the social and humanitarian fields, where the Salafi movement is very active.

Preventing violent extremism

Haraki Salafis also have a role to play in the prevention of unlawful violent jihadism. Because they share and adhere to the same religious norms and beliefs they have a certain legitimacy amongst Salafi militants. This puts them in a position to do three things. First, they can offer potential jihadis an alternative: action through political participation, rather than violence, as a means to express their political views. Second, they can credibly challenge the religious justifications for violence of the Salafi jihadi groups. Third, in certain circumstances, they may be able to open channels of communication to engage directly in debate and discussion with violent jihadi groups in an effort to prompt reflection within such groups about the desirability of using violence.[5] In order to be able to maintain the credibility to do this Haraki groups must carefully preserve their political independence. Any hint of instrumentalization by the state or foreign actors will immediately compromise their credibility and endanger them.

Reluctance to promote Salafi political participation

Particularly in Western policy circles, there is nervousness about promoting Salafi political participation. In part this is linked to a hesitancy to support political viewpoints which seem to contradict Western values, for example regarding the status and rights of men and women. However, any actor that is serious about democracy promotion has to accept that a consistent and credible approach must include promoting the inclusion of actors with alternative views. Exclusion will undermine claims that democratic values are being respected and remove the opportunity for open debate on issues where differences of opinion in society exist.

Skeptical voices also question the commitment of Salafi parties to democracy. However this second-guessing of motivations is based on a number of untested assumptions. Rather than pre-judging their intentions, is it not fairer to give them a chance to prove their commitment through their actions?

Conclusion

A key part of supporting democratic development must be the fostering of an inclusive politics which offers all viewpoints representation in the political arena. Haraki Salafi groups are an opportunity for the Salafi viewpoint to be represented in politics. By supporting spaces where Salafi groups can learn and work together with groups of other persuasions, third parties can help to reinforce the knowledge, attitudes and relationships necessary for the inclusive politics that democracy requires. This is not only good for democracy but also for peace, strengthening a legitimate alternative to jihadi Salafi groups.

Further Reading

The Salafiscape in the wake of the ‘Arab Spring’ Abbas Aroua, The Cordoba Foundation Geneva, 2014, http://www.cordoue.ch/publications/papers/item/369-the-salafiscape-in-the-wake-of-the-arab-spring. This research paper by a peacebuilding practitioner who works closely with Salafi groups offers a succinct overview of the origins of Salafism and the different trends that have emerged since 2011.

Global Salafism: Islam’s New Religious Movement Roel Meijer, Oxford University Press, 2009. An edited volume that offers an in-depth look at the origins of Salafism and its increasing relevance for global politics.

Preventing Violent Extremism through Inclusive Politics in Bangladesh Geoffrey MacDonald, United States Institute of Peace, 2016, http:// www.usip.org/publications/2016/01/14/preventing-violent-extremism-through-inclusive-politics-in-bangladesh. This Peace Brief argues that repression of Islamic parties in Bangladesh is fueling violence and that efforts to strengthen democratic governance and inclusive politics could help mitigate this trend.

Selected Sources[1] For more on the origins of the terms used in this typology see Mohammad Abu Rumman, “The Salafist in the Arab Spring: Challenges and Responses” in Anja Wehler-Schoeck (ed.) Salafist Transformations: Significance, Implications and Prospects, Amman: Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung, 2013, pp 7 – 10.

[2] Jammi/Madkhali groups are not necessarily non-violent. In Libya, such groups recently formed armed groups in support of pro-regime General Haftar.

[3] There are some exceptions. In Kuwait, for example, Salafi groups have been active in politics since the 1980s and holds several seats in the parliament.

[4] A concrete example of such support activities is the work of the Cordoba Foundation Geneva and the Swiss Federal Department of Foreign Affairs who organized a series of three workshops to engage Haraki Salafis. The first focused on moving from the logic of preaching to political participation, the second on coalition-building and the third on participation in challenging environments. See Alistair Davison, Lakhdar Ghettas, Halim Grabus and Florence Laufer, Promoting Constructive Political Participation of New Faith-Based Political Actors in the Arab Region. Cordoba Workshops Reports. The Cordoba Foundation of Geneva (2016). Available at www.cordoue.ch

[5] For a discussion about engaging different trends in Salafism to counter jihadi Salafi groups see Markaz blog discussion, “Experts weigh in (part 10): Is quietest Salafism the antidote to ISIS?”, The Brookings Institution, 27.04.2015, http://www.brookings.edu/ blogs/markaz/posts/2015/04/27-quietist-salafism-post-salafism-charlie