Azerbaijan’s New Macroeconomic Reality: How to Adapt to Low Oil Prices

6 May 2016

By Ingilab Ahmadov for Center for Security Studies (CSS)

This article was originally published in the CSS' Caucasus Analytical Digest No. 83 on 21 April 2016.

Abstract

Despite the accumulation of significant revenues from crude oil exports and remarkable economic growth over the past 15 years, Azerbaijan’s economy has been hit hard by the recent drop in global oil prices and has experienced a period of painful economic adjustments. The government has attempted to change the traditional distributive approach that is based largely on oil revenue distribution in favor of a new earning-oriented model that is expected to benefit from a robust non-oil sector. It is clear that the oil price slump caught the government off guard and poorly prepared to cope with the new low price environment. Clearly, it will be difficult to build a new model of development quickly and thoroughly in a short period of time. While the availability of the state oil fund reserves mitigates the risk of financial and macroeconomic collapse in the near future, the effects of a large informal economy make it difficult to regulate the economy using only conventional instruments, such as money supply and credits. Thus, to be effective, authorities’ anti-crisis measures should be accompanied by institutional and administrative reforms.

Oil Price Drop and National Currency Devaluation

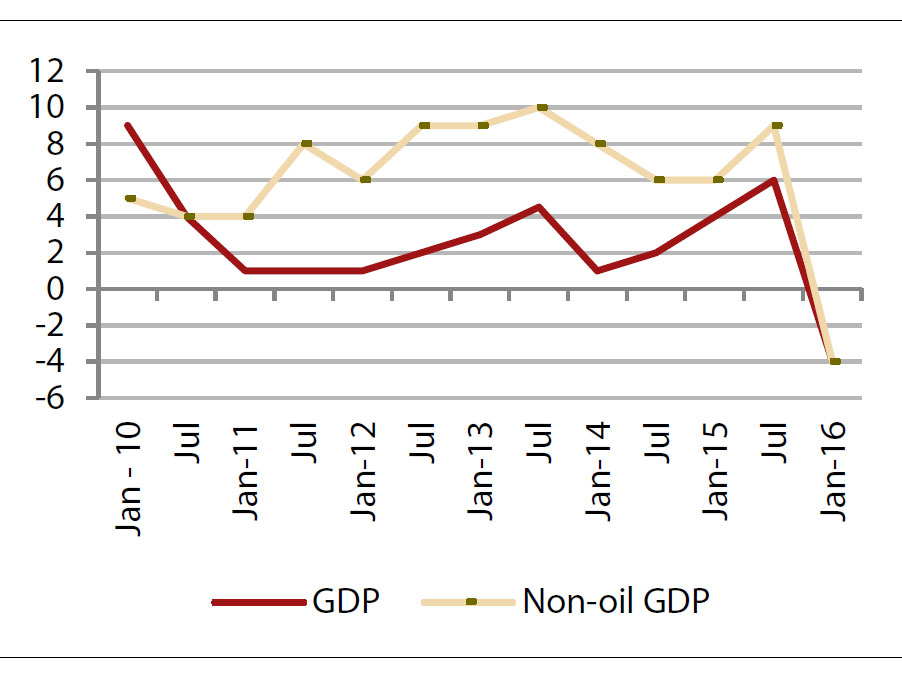

Azerbaijan is one of the most oil-dependent countries in the world. In 2015, the oil sector generated 31% of the country’s GDP (compared with 52% in 2011), and oil revenues accounted for 63% of the state budget and amounted to 86% of total exports. Unsurprisingly, as in other oil-dependent economies, the drop in world oil prices has had a significant impact on Azerbaijan’s economy. Moreover, the consequences turned out worse than expected. Last year, the Azerbaijani currency (manat) was devaluated twice and lost most of its value.

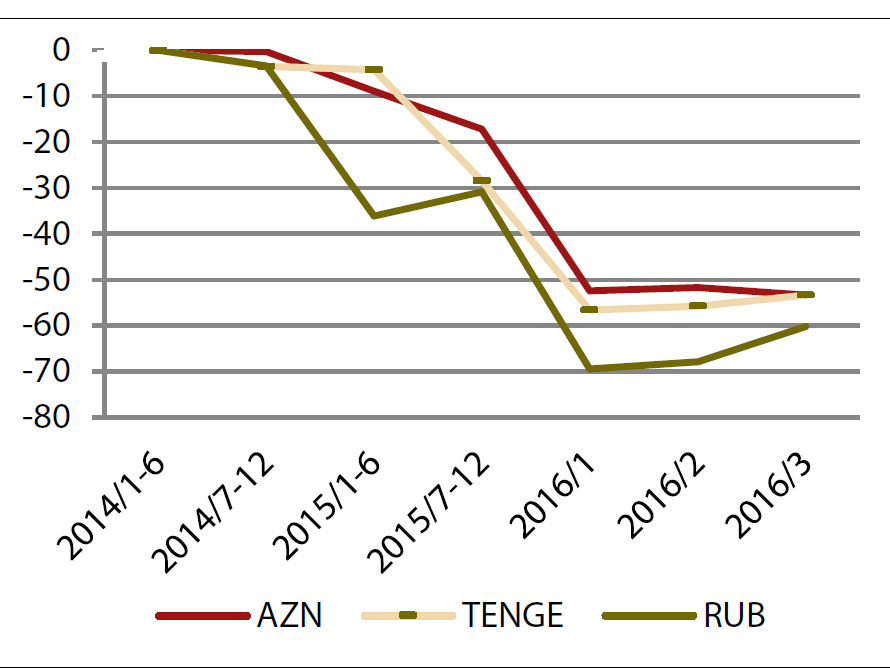

Similar to other oil-rich Caspian Basin states, namely Russia and Kazakhstan, Azerbaijan’s national currency lost its value relative to the U.S. dollar and Euro. However, whereas Russia and Kazakhstan began to weaken their national currencies in 2014, Azerbaijan held its currency at a firmly stable rate in the hope of a return to favorable oil prices. Another peculiarity in this case is that both times that Azerbaijan devalued its currency, it did so sharply and not smoothly, which differs from the approach taken by Russia and Kazakhstan. Of course, in the Russian case, sanctions have had a significant impact on the ruble as well.

In terms of macroeconomic implications, currency devaluation was considered not only as a way to maintain monetary stability but also as a measure of fiscal and budget stabilization. As in Russia and Kazakhstan, the Azerbaijani state budget consists mainly of oil and gas revenues and therefore devaluation of the local currency allows the country to generate and transfer more earnings from the export of crude oil because the currency of the oil trade is the U.S. dollar.

Figure 1: Devaluation of the National Currencies in Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan and Russia in Light of Low Oil Prices (Source: Author’s calculation based on statistical data from the

central banks of the three countries).

The new socio-economic environment that emerged thereafter was painful for all social groups but particularly for the most vulnerable. Most investment programs, including public investment projects financed through the state budget and the State Oil Company (SOCAR), have been curtailed. SOCAR’s capital-intensive investment projects were frozen, such as construction of a new oil refinery worth an estimated US$ 18 billion.

Following the manat’s devaluation, the country’s ranking in the world economy fell sharply: GDP per capita dropped 56%. By the end of 2015, annual GDP per capita in Azerbaijan stood at US$ 7,986; at present, that amount is only US$ 3,490.

Two other indicators are noteworthy as well. Before the national currency devaluation, Azerbaijan’s public debt to GDP ratio was one of the lowest among oil-producing states, but today this is no longer the case. Public external debt to GDP (as of January 1, 2016) stands at 19.8%, whereas it was only 8.6% one year before (Ministry of Finance of Azerbaijan).

Fortunately for Azerbaijan, in the post-devaluation period the assets of the State Oil Fund (SOFAZ) are expected to rise to almost 100% of GDP this year (up from approximately 50% of GDP in 2014). This is the highest indicator among oil-rich countries in the region, where comparable figures for Russia and Kazakhstan are 10% and 35%, respectively.

Figure 2: Azerbaijan: GDP Growth Rate, 2010–2016 (% change, year-to-year, year-to-date, preliminary monthly estimate)( Source: The Economist Intelligence Unit)

The State Oil Fund of Azerbaijan as an Airbag

Azerbaijan’s oil revenue management system is based on combining SOFAZ and public budget mechanisms, whereby most oil revenues accumulate in the Fund and will be used for future spending on various investment projects directly and through the state budget.

As the biggest share of annual expenditures of the Fund are transfers to the state budget (in 2015, 88 % of SOFAZ expenditures were transfers to the public budget, amounting to 47% of the state budget revenues), in this current period of rapid change, this factor became a good benchmark at which to peg the exchange rate and prevent further devaluations of the manat.

From January to mid-March 2016, SOFAZ sold US dollars worth more than US$ 1 billion at a newly created auction marketplace, which is a significant opportunity for the domestic exchange market. It was a necessary step, as SOFAZ has to make regular transfers to the state budget in manat. In addition, this helps the Central Bank of Azerbaijan (CBA) to save its foreign reserves. Notably, the government has shown no intention of expanding the use of SOFAZ’s assets to maintain the fiscal balance, as was the case with some other oil exporting states. Instead, the dramatic devaluation of the national currency gives the government an opportunity to save more of the Fund’s assets for the future.

The Favorable Oil Climate of the 2000s

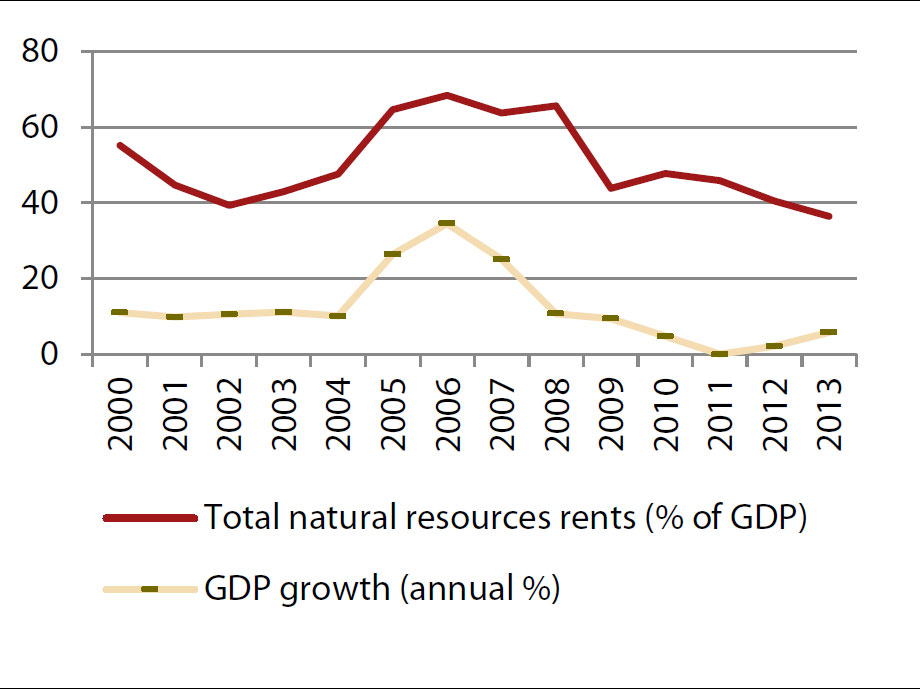

The last decade’s commodities super cycle was quite beneficial for Azerbaijan’s economic growth. Fortunately, this period coincided with an increase in Azerbaijani oil production following the signing of the “Contract of the Century” for the Azeri-Chirag-Guneshli deepwater fields, explored and developed in cooperation with global oil giants, including BP, ExxonMobil, and other multinationals.

Between 2004 and 2011, Azerbaijan’s GDP growth was 15%, on average. In comparison, Russian GDP growth for this period was 4%, and Kazakhstan’s growth was 7%.[1] Due to the enormous oil revenues generated during this favorable oil price super cycle, Azerbaijan’s public budget grew by more than a factor of 25. All three countries established a sovereign wealth fund (in Russia, two funds), which have accumulated sizeable financial reserves.[2] These funds are expected to contribute to financial stability in the long run. By the end of 2014, the total amount accumulated in Russia’s National Welfare Fund and Reserve Fund was estimated at US$180 billion (9% of GDP). Moreover, the National Fund of Kazakhstan had accumulated US$ 69 billion (30% of GDP), while the State Oil Fund of Azerbaijan (SOFAZ) had accumulated US$ 36 billion (47% of GDP).

The current financial turmoil calls the official opinion of the government into question. During the oil boom period, Azerbaijani authorities declared that the country had reached a sufficient level of socio-economic sustainability. Moreover, the chaotic decisions of the government indicate that it prepared poorly for low commodity prices. The government does not seem to have any clear strategy for adapting to the new reality.

Another essential problem is the disparity between official statistical information and the real picture, such as the volume of real cash flow (dollarization), traded goods in the domestic economy (some imported goods are not declared at the customs agency), tax avoidance, and other practices that constitute the informal economy. Ultimately, the cause of this disparity is the inefficiency in the existing institutional framework, including customs, tax collection, and antimonopoly agencies.

According to official statistics, the volume of the informal economy is 7% of GDP, which is likely to be a modest estimate. World Bank experts’ calculations put the extent of informal economic activity at 32% of the country’s GDP as of 2008.[3]

The negative consequence of the informal economy for the government, which needs to tackle exchange rate stability and predictability, is a lack of effective monetary and other economic instruments to influence the market. The sizeable informal economy implies there is an unaccounted amount of dollars in cash holdings, sales, services transactions, and household real income. It also points to widespread tax evasion. Informal transactions impede the implementation of an effective macroeconomic policy.

The government’s lack of a holistic approach to managing oil price downturns and its weakness in designing an anti-crisis program comprise another set of problems that became clear during the ongoing perturbations that began at the end of last year. The effective coordination of monetary, fiscal and social policies, based on a clear set of priorities in the post-oil period, which seems to have begun, is now the government’s most important challenge.

However, Azerbaijan’s predicament is not merely a consequence of low commodity prices. The country’s economic problems were mounting before the crisis due to the poorly diversified structure of its economy and the absence of strict fiscal rules. Beginning in 2005, the enormous expenditures associated with ineffective and non-transparent spending show the economy in a negative light.

Today, amidst macroeconomic deterioration, it is clear that something went wrong. As British economist Paul Collier put it, “And the supercycle of the last ten years has been the biggest opportunity that they’ve had in history. And for most of them, it’s been a missed opportunity. And so it’s really important, society by society, to discover what went wrong and what is needed to be understood in order for next time to go better.” [4]

Figure 3: Azerbaijan: GDP Growth and Total Natural Resource Rents (%) (Source: The World Data Bank, World Development Indicators)

How Successfully Has the Government Reacted?

The government is taking active steps to tackle the challenges of macroeconomic balancing. Its policy actions so far may be divided into three groups:

1. Strengthening Financial Security and Predictability

Until now, the government has mostly concentrated on exchange rate stability. Immediately following the December 2015 devaluation, the financial sector endured chaos for some time, and the government did its best to prevent further instability of the national currency. As usual, the further decline of the manat led to speculations on the black market. The first steps were nervous, chaotic and unsystematic. The government decided to close exchange offices and concentrated all exchange operations only in the banks and their branches. It was clear that this reaction was associated with the flight of capital. Finally, the government successfully maintained the stability of the exchange market and tackled the foreign exchange rate. For this, it used additional interventions from the foreign currency reserves of the central bank (CBA).

Some administrative steps were also taken, such as the establishment of a new legal entity called the Financial Market Control Chamber. The mission of this entity is to ensure public control of the country’s securities market, investment funds, banking and insurance sectors, as well as the flexibility and transparency of the activities of payment systems (www.president.az). Due to the changes to the Law on Banks, some functions of the CBA were delegated to the newly established Control Chamber. The changes also downgrade the CBA’s powers of supervision over the banking sector.

2. Liberalization of the Economy and Improving its Entrepreneurship Space

It is clear that an essential reason for the painful ramifications of the commodity price decline in Azerbaijan is the lack of a robust and competitive domestic business sector. The economic diversification policy, declared as a priority at the start of the oil boom, was not realized in practice. Barriers to stimulating domestic business development are mostly problems involving access to capital markets and monopolization of most segments of the markets. These distortions prevent the growth of local businesses. If the windfall of oil revenues compensated for the lack of an open business environment during the oil boom, the absence of a competitive environment today hampers the recovery of the economy over the long term.

Over the last two months, the President of Azerbaijan has issued more than a dozen decrees and other official documents aimed at encouraging local business development. This business support program includes the following measures: i) promotion of non-oil products for export, ii) reform of the customs agency, and iii) simplified procedures for issuing licenses and permits.

These decisions should give the business environment the necessary momentum to stimulate real economic diversification and eventually reduce the country’s heavy dependence on petroleum.

3. Institutional Reforms to Support Development of the Non-Oil Sector

Institutional reform seems to be the most difficult task but is crucial if Azerbaijan is to adapt to the new low oil price era and build a desirable model of development that is sustainable in the long term.

Like many other oil dependent countries, the government of Azerbaijan is also considering privatization of state property as leverage and as an incremental source of budget income. Notably, the government did not pay adequate attention to privatization during the super-cycle oil boom of the 2000s, neither as leverage for business development nor as a source of revenue for the state budget. In the case of the budget, this was not necessary as oil revenues covered the budget needs with excess remaining.

Thus, most of the state property inherited from the Soviet legacy had little business potential and was essentially trash. In this regard, the Presidential decree on privatization of February 16, 2016 should be considered a continuation of the “State Program of Privatization of State Property” dated 10 August 2000.

All these efforts are necessary, but not sufficient. The government should recognize that the weak currency opens up enormous opportunities for local business, particularly farmers. However, in order to fully realize the potential of the emerging new environment the government should undertake fundamental liberalization reforms that would streamline the work of customs services and address the omnipotence of local authorities.

Conclusion

In sum, it is evident that the US$ 34 billion sovereign wealth fund (SOFAZ) diminishes the risks of financial and macroeconomic collapse in the near future. In practice, the rainy day oil fund operates as an airbag more or less successfully. Bolstered by significant foreign currency reserves, SOFAZ helps fix the fiscal deficit. The oil fund plays an active role in stabilizing the exchange rate by withdrawing the strategic currency reserves from the central bank and selling US dollars at currency auctions. In 2015, the central bank depleted US$ 9 billion of its strategic reserves to defend the national currency from sliding against the dollar.

However, the presence of a large informal economic sector makes it difficult to regulate the economy using only traditional instruments, such as money supply and credits. The official macroeconomic statistical accounts, particularly money indicators, may not accurately reflect the real picture. This is not only due to the imperfect work of the statistical agency. Typical institutional problems impede the gathering of information concerning customs- and tax-related transactions. Therefore, it is important to ensure that the government’s anti-crisis steps are backed by institutional and administrative leverage. Without institutional reforms, it is unrealistic to expect that the anti-crisis policies will yield substantive and successful results.

Notes[1] UN, World Economic Situation and Prospects 2013,

[2] Ingilab Ahmadov, Stela Tsani, and Kenan Aslanli, “Sovereign Wealth Funds as the Emerging Players in the Global Financial Arena”, Public Finance Monitoring Centre and Revenue Watch Institute (2009),

[3] Yasser Abdih and Leandro Medina, “Measuring the Informal Economy in the Caucasus and Central Asia”, IMF Working Paper WP/13/137, May 2013,

[4] Paul Collier, “The Decision Chain of Natural Resource Management (I)”, Global Heritages, February 5, 2016, .