Responding to Security Challenges in East Asia: Three Perspectives

11 May 2016

By John Ravenhill for Centre for International Governance Innovation (CIGI)

This article was external pageoriginallycall_made published by the external pageCentre for International Governance Innovation (CIGI)call_made in April 2016.

INTRODUCTION

East Asia presents a fundamental paradox for international relations scholars.[1] Despite having arguably more sources of interstate tension than any other region of the developing world, there has not been significant interstate conflict in the area since the end of the China-Vietnam war in 1979. How can this paradox be explained? And to what extent have recent developments undermined those factors that have preserved the “long peace” in East Asia over the past half century? This paper will address these central questions. First, however, it will briefly review the sources of the principal security challenges facing East Asian states:

- East Asia has more contested boundaries than any other part of the world. Although attention has focused in recent years on disputed maritime boundaries in the East and South China Seas, many competing claims over land boundaries also remain unresolved. M. Taylor Fravel (2014, 527) estimates that Asia accounts for 40 percent of all active territorial disputes worldwide. Only on rare occasions have parties settled boundary disputes either through bilateral negotiations (for instance, China and Vietnam signed a border delimitation treaty in December 1999) or through international arbitration (for instance, the International Court of Justice determination in 2008 of the Pedra Branca dispute between Malaysia and Singapore). Unresolved disputes often fester for years, providing latent ammunition that populist politicians can exploit at some point.

- The unprecedented economic growth of East Asia has produced more rapid shifts in inter-country power differentials than has occurred elsewhere in the world, generating challenges for existing dominant powers to accommodate newcomers. Theorists of international relations have frequently asserted that the international system is most prone to conflict during periods of power transition (Organski 1958; Gilpin 1981).

- East Asia is arguably the region with the greatest political diversity in the world, ranging from longestablished liberal democracies to thriving new democracies such as Indonesia, to four of the world’s five surviving communist regimes, including the bizarre autocracy of North Korea (the others being China, Laos and Vietnam).

- Military expenditure in East Asia is growing more rapidly than in any other region of the world apart from Africa (whose base expenditure on which the growth figures are calculated was substantially lower than that of East Asia) (Stockholm International Peace Research Institute [SIPRI] 2015). Adjusted for inflation, military spending in East Asia grew by 76 percent in the period from 2005 to 2014. Three of the countries with the highest military expenditures in the world are in East Asia: China, Japan and South Korea. If the broader context in which East Asian security relations are embedded is considered (and here it is important to note the increasing salience of South Asia to East Asian military affairs, in particular with the increasing attention being given to sea lane security), then four more of the top 15 are added: the United States, Russia, India and Australia. Looked at from this broader context, the East Asian security environment includes six of the world’s nine confirmed nuclear powers.

APPROACHES TO EAST ASIAN SECURITY AND CONTEMPORARY CHALLENGES

Explanations for the long peace in East Asia are conventionally categorized into three groups: those that emphasize the importance of a balance of power and the role of military alliances; those that focus on the distinctiveness of East Asia and the role of its regional institutions, in particular ASEAN; and those that argue that high levels of economic interdependence make the waging of war prohibitively costly. Over the last 15 years, observers of the region have increasingly acknowledged that these alternative approaches can be complementary, adding to our understanding of the complex interactions that have preserved the long peace in the region. Analytical eclecticism, in the words of Peter J. Katzenstein and Rudra Sil (2004), has been seen as preferable to the inter-paradigmatic squabble that has often characterized academic writing on East Asian security, even if, to paraphrase William Tow (2009, 9), a “potpourri” approach runs the risk of producing a melange of arguments that, even if compatible, are essentially non-refutable.

Hegemony and Balancing in East Asia

The period immediately after the fall of the Berlin Wall saw an outpouring of scholarly work predicting that the principal locus of interstate conflict would shift from Europe to Asia: the Asian region, in the words of the title of one widely cited article, was “ripe for rivalry” (Friedberg 1993). In addition to this classic realist argument regarding the inevitability of conflict in a region characterized by disparate political regimes, increasing inequality in development levels and weak institutions, other writers from a realist perspective asserted that regional stability had been and could continue to be sustained by the astute pursuit of balance-of-power politics. Ralf Emmers (2003) noted, for example, that balance-of-power considerations had been prominent even in the regional organization, ASEAN, considered to be the most prominent example of an institution based on cooperative security principles.

Other writers put emphasis on the US-centric alliance network — the so-called “San Francisco system” — as providing the essential foundation for regional stability in Asia (Calder 2004). Ambiguities were always evident in these characterizations, however. The San Francisco system was even less of a balanced alliance than that which linked the United States to Western Europe in the Cold War. Rather than the alliances themselves, it was US hegemony that guaranteed the peace of the Asian region. And, arguably, it did so for a period with considerable success — not only did it discourage Chinese and North Korean adventurism, but also kept the genie of Japanese militarism firmly in the bottle, which ensured that Beijing, if not an enthusiastic supporter, nonetheless found that its interests for much of the last four decades also coincided with the United States playing a hegemonic role.

But this was largely a unilaterally maintained order. Much consequently depended on attitudes in Washington — and when the United States was preoccupied with developments in other parts of the world, as was the case in the first decade of the twenty-first century, Asia suffered from less-than-benign neglect. Moreover, as Michael Mastanduno (2003, 143) notes, what the United States was able and willing to achieve was limited: “although US officials have helped to defuse regional crises, they have failed to foster any fundamental resolution of these crises or their underlying causes.”

Furthermore, the San Francisco system, as a network of bilateral alliances, had the consequence — intended or not — of inhibiting the development of region-wide security institutions. Washington, Mastanduno (2003, 152) comments, has always regarded multilateral initiatives in Asia as supplements to rather than substitutes for its network of bilateral alliances. The regional institutions with a security focus that did develop — the ASEAN Regional Forum (established in 1994) and the East Asia Summit (established in 2005) — have frequently been criticized as being little more than talking shops in which well-rehearsed positions are repeatedly restated (Dibb 2002).

In the last decade, there have been increasing doubts regarding the capacity of a balance-of-power approach, as practised in Asia over the last half century, to continue to sustain a durable peace. Various developments have indicated that the region may be heading for the instability that authors in the realist tradition predicted at the end of the Cold War.

In criticizing the approaches that suggested that Asia would be prone to conflict in the post-Cold War era, David C. Kang (2003a, 62) identified a number of predictions in the literature that had not been realized: “the growing possibility of Japanese rearmament; increased Chinese adventurism spurred by China’s rising power and ostensibly revisionist intentions; conflict or war over the status of Taiwan; terrorist or missile attacks from a rogue North Korea against South Korea, Japan, or even the United States; and arms racing or even conflict in Southeast Asia, prompted in part by unresolved territorial disputes.” This assessment now seems premature. In July 2015, the government of Japanese Prime Minister Shinzō Abe pushed through legislation in the House of Representatives that revised the interpretation of the “pacifist” Article 9 of the constitution, permitting the deployment of Japanese military forces overseas if Japan or a close ally is attacked. In the last few years, the share of military expenditure in Japan’s GDP and budget has expanded. Japan’s moves are, in part, in response to the new assertiveness of China, especially in regard to the disputed Senkaku islands and its territorial claims in the South China Sea (SCS). China appears to have changed course after years in which it often appeared to go out of its way to assure countries in the region of its cooperative approach through proclaiming that it was following a path of “peaceful development,” and through what was characterized as a “charm offensive” (Kurlantzick 2007). The country’s newly assertive foreign policy and the nationalist stance adopted by the government of Xi Jinping have unnerved its neighbours. To be sure, the Taiwan issue has been quiescent during the period of Kuomintang rule in Taipei. However, the other realist predictions from a quarter of a century ago have contemporary resonance. The North Korean regime continues to develop its missile and nuclear technologies and shows little interest in the Six Party Talks. Meanwhile, in Southeast Asia, governments are investing unprecedented amounts in modernizing their armed forces and, in particular, in acquiring new force projection and offensive capabilities. Some countries have acquired submarine fleets for the first time (in January 2014, Vietnam took delivery of the first of six Kiloclass diesel-electric submarines purchased from Russia; Thailand and the Philippines have plans to purchase two and three submarines respectively; Indonesia, Singapore and Malaysia have substantially strengthened their existing capabilities).

This context has ensured that the Obama administration’s “pivot to Asia” (subsequently retitled a “rebalancing” of US foreign policy) has been welcomed in many parts of the region. America’s traditional allies — the Philippines, Singapore and Australia — have all entered into agreements allowing US forces enhanced access to local bases. And in May 2015, Tokyo and Washington signed new Guidelines for US-Japan Defense Cooperation that permit Japanese forces to act when the United States or countries the United States is defending are attacked. In the same month, the United States sent a surveillance plane to challenge China’s assertiveness in the SCS amid reports that it planned to establish an air defence identification zone similar to the one that Beijing had proclaimed in the East China Sea. While the increased US presence has reassured some allies, it has caused concerns for others: South Korea, for instance, expressed alarm at the proposed expansion of Japan’s military role. Some commentators worry that the new US stance will reinforce divisions within the region, undermining attempts at cooperative security, and that by failing to accommodate China’s rise, will ultimately lead to a situation where countries are forced to choose between China and the United States (White 2012). Moreover, doubts remain on the sustainability of the US commitment beyond a Democrat presidency, given the isolationist sentiments of many Republican presidential contenders and a public opposed to the costs of US foreign engagement, and indeed the limits to US capacity to preserve a traditional balance of power and shape regional outcomes as China increasingly challenges its preponderance (Campbell, Patel, and Singh 2008).

Institutions and Elite Socialization: An “Asian” Approach to Regional Security

The second group of explanations for Asia’s long peace focus on unique characteristics of the regional security environment, in particular, on the manner in which Asian cultural norms shape diplomatic interactions and on the socializing role of regional institutions, especially ASEAN. In rejecting the pessimism of realist arguments that Asia is doomed to experience the power politics that produced conflict in the European arena, analysts start with the notion that the focus should be on what Barry Buzan and Ole Waever (2003) have termed “regional security complexes,” each of which has unique configurations of drivers of international interactions. Kang (2003b) makes the argument that Asian diplomatic history has been very different from that of the West, with order maintained for many centuries by a largely benign Chinese hegemony. Asian countries, therefore, may not be alarmed by China’s resumption of a dominant role in the region or seek to balance against it. Writers from a constructivist perspective emphasize instead the role that regional institutions have played in institutionalizing cooperation and in socializing elites into cooperative forms of interaction (Acharya 2001; Khong and Nesadurai 2007; Ba 2009).

Regional institutions, however, have not fared well over the last decade. ASEAN’s demand to be “in the driver’s seat” in Asian integration has increasingly come under challenge. It now faces significant competition from other institutions, some of which are based on a broader conception of region than East Asia alone. The East Asia Summit, for instance, which includes India, Russia, the United States and Oceania, has a security remit that overlaps with the ASEAN Regional Forum. Meanwhile, the US-backed Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) divides ASEAN, with only four (Brunei, Malaysia, Singapore and Vietnam) of ASEAN’s 10 member states currently invited to participate in what Washington identifies as the core economic component of its “pivot” to Asia. The TPP competes with ASEAN’s own proposed economic grouping, the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership, which builds on ASEAN relations with its “Plus One” partners (Australia, China, India, Japan, South Korea and New Zealand). And, in the face of the “deep integration” promoted by the TPP, the ASEAN Economic Community looks superficial at best.

ASEAN has enjoyed little success in resolving conflicts among its own members or between them and other regional actors. Commentators have frequently noted that ASEAN’s strength has been in conflict avoidance rather than conflict resolution, that is, to distract from disputes in the hope that protagonists will find that the benefits from cooperation in other domains will outweigh anything that can be achieved through interstate conflict. The consequence is that some long-standing territorial disputes between ASEAN members continue to fester. One of the most notable is between Cambodia and Thailand, which brought two ASEAN countries closer to a significant military confrontation with one another than had occurred in the previous three decades. Even one of the best-known enthusiasts for ASEAN, Amitav Acharya (2013, 6), has acknowledged that ASEAN does not currently constitute a security community, that is, a grouping of states among whom war is unthinkable.

ASEAN has been unsuccessful in fashioning a consistent and coherent approach among its members to the most significant location of territorial contestation in the region, the SCS. Complicating matters for ASEAN is that not all of its members are claimants in the SCS, which makes it easier for Beijing to sustain its argument that negotiations should take place on a bilateral basis between it and individual ASEAN states rather than with ASEAN as a collectivity. Cambodia’s support for China’s position when it held the ASEAN chair in 2012 prevented the grouping from issuing a joint declaration on the SCS: in March 2015, the Cambodian prime minister, Hu Sen, explicitly endorsed the Chinese approach that denied a collective role to ASEAN (Sothanarith 2015).

ASEAN, in reality, has suffered a leadership deficit for much of the last two decades, starting from the coincidence of two developments: membership expansion and the Asian financial crisis. Laos and Myanmar became members of ASEAN in July 1997, exactly the time of the onset of the financial crisis (Cambodia joined two years later). Expanded membership exacerbated the diversity of the grouping — both economically, with the three new members being by far the poorest countries among ASEAN members (with per capita incomes only half of that of the Philippines, the next poorest country), and politically. At a time when most of the other countries in the region were moving, albeit at different speeds, toward democratization, expansion brought into the ASEAN fold one communist regime (Laos), a military dictatorship (Myanmar) and a state (Cambodia) headed by a former Khmer Rouge official that regularly records among the worst scores within the region on rule of law indices. The membership of these three regimes has stymied the efforts of the region’s democracies — most notably the Philippines and Indonesia — to have ASEAN take a stronger stance on human rights in its member states. The Asian financial crisis, meanwhile, led to the removal of the Soeharto regime in Indonesia, which had been the principal source of leadership in the grouping over the previous two decades (Smith 1999; The Economist 2012).

Economic Interdependence

For the third school of thought, the explanation for East Asia’s long peace lies in the incentive structure created by the manner of incorporation of East Asian countries into the global economy. Transformations in the character of economic interdependence have had a profound impact on interactions among states in East Asia because they have significantly increased the costs of interstate conflict. How groups conceive of their interests inevitably shapes the strategies that they adopt. In turn, the relationship between interests and ideas is one of multiple feedback loops.

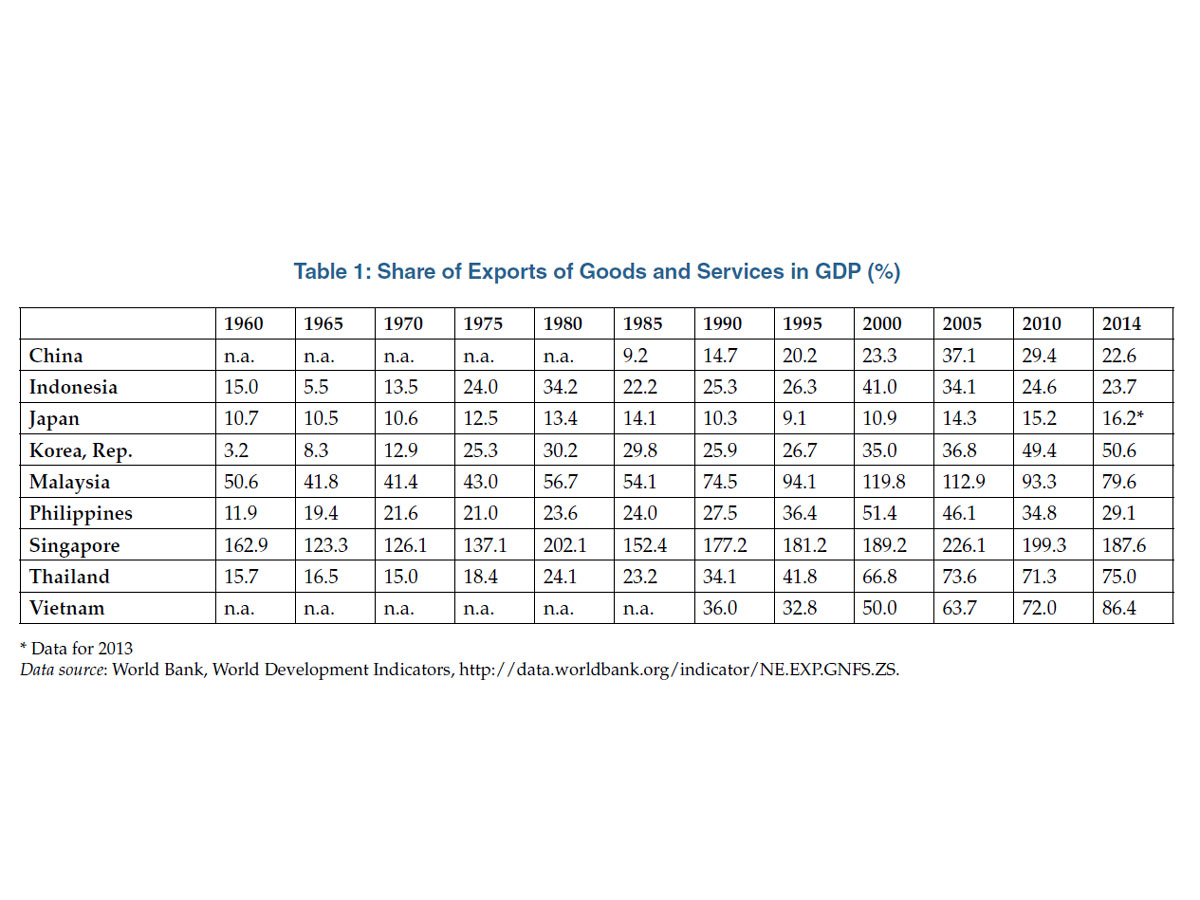

Changes to East Asian economies’ integration in the global economy have both quantitative and qualitative dimensions. Trade became far more important for most East Asian economies over the last half century, but especially in the years between the mid-1980s and the global financial crisis. For a number of countries, the share of trade in GDP has failed to recover to the levels experienced in the first decade of the century — the exceptions being Japan, Korea, Thailand and Vietnam (see Table 1).

The mid-1980s were an important turning point. Many economies, especially those in Southeast Asia, began a process of unilateral liberalization of trade in response to the collapse of commodity prices in the first half of the decade. The transformation of their trade patterns was reinforced by the growth in production networks that followed the currency realignments brought about by the 1985 Plaza Accord. The construction of a new regional division of labour was subsequently profoundly affected by China’s opening to the world after 1978.

Production networks (sometimes referred to as global value chains [GVCs]) have been the principal engines driving Asia’s remarkable economic growth in the last quarter of a century. Their spread has led to high levels of intraregional trade, in particular in mechanical and electrical components. Global production networks have, in the words of the World Trade Organization’s (WTO’s) former director general, Pascal Lamy, produced “a new paradigm where products are nowadays ‘Made in the World’” (WTO 2010). For economists, these new trends in production and trade have been driven primarily by technological developments, in particular reductions in transport costs, and by the lowering or removal of tariffs and other barriers to trade. Together these have enabled components to be moved at relatively low cost around the region in order to take advantage of differences in factor costs and concentrations of skills. These elements, often seen as the key features in what is portrayed as Asia’s “market-led” development, have indeed been important. Nonetheless, the role of governments in facilitating the growth of production networks should not be overlooked. Their contribution over the last quarter of a century has taken many forms: the establishment of export-processing zones that permitted duty-free import of components for assembly into products that were subsequently exported, and which were the basis for the early footholds that many countries in the region, including China, gained in these networks; similar non-geographically specific provisions through duty-drawback arrangements; the unilateral lowering of tariffs; and government commitments in regional and global trading agreements, not least the 1996 Information Technology Agreement (significantly extended in July 2015) that freed up a substantial part of trade in the region’s single most important export sector (Ravenhill 2014).

The fragmentation of production has arguably been more important in driving economic growth in East Asia than elsewhere in the world. World trade in components increased substantially in the first decade of the twentyfirst century, up from 24 percent of global manufacturing exports in 1992-1993 to 46 percent of the total in 2006–2008. In the same period, the share of developing economies in network exports doubled, primarily because of growth that occurred in East Asia. In 2007-2008, exports within production networks accounted for fully 60 percent of East Asia’s manufacturing trade, in comparison with a world average of 51 percent. The figure for ASEAN was higher still, with more than two-thirds of its manufactured exports taking place within production networks (Athukorala 2014, Table 4). Production networks do not merely provide entree to markets — they also provide access to the technological know-how essential to competing in the global economy. And in some cases, increased flows of foreign direct investment are also associated with the growth of networks. United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) (2013b, 20-21) calculations indicate that those countries with greater participation in GVCs experience higher rates of growth in per capita GDP.

With all the economies in the region more open than before, domestic welfare depends overwhelmingly on participation in production networks — “Factory Asia” in Richard Baldwin’s (2011) terms. Political stability and economic growth are intimately intertwined. Where growth rates have faltered, regimes have come under increasing challenge — a notable example being the overthrow of the Soeharto regime in Indonesia during the Asian financial crisis. The legitimacy of East Asian regimes has long rested on their capacity to deliver economic growth: nowhere is this more true than in China, where most economists estimate that the economy needs to grow by around seven percent annually to absorb the influx of migrants from rural areas. The increased importance of exports for economic growth together with the incorporation into GVCs has transformed the nature of interdependence, the mechanisms through which economic growth is achieved, and greatly increased the costs of a fracturing of links with the global economy that would result from interstate conflict. According to calculations by UNCTAD (2013a, 12), close to 60 percent of China’s exports are linked to participation in GVCs. Estimates for the share of foreign components in China’s manufactured exports range from 30 to 50 percent (UNCTAD 2013a; Koopman et al. 2010).

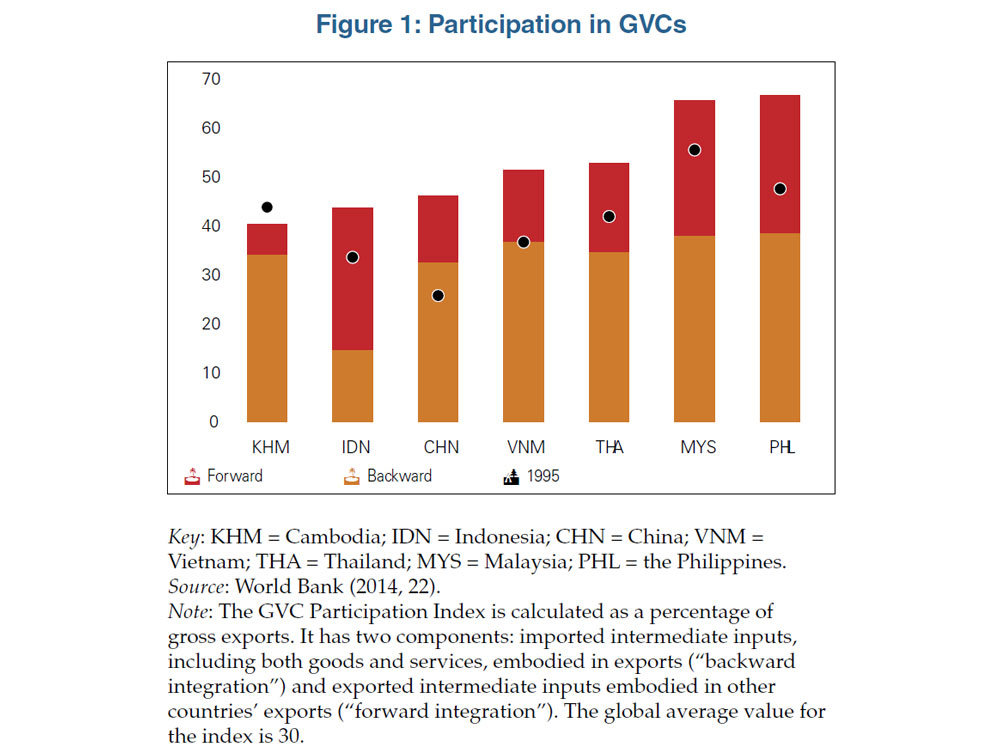

Cross-border exchange of components constitutes a far larger share of interregional trade in East Asia than elsewhere in the world (see Figure 1). Contrary to the expectations of some observers at the time of its accession to the WTO in 2001, China’s growth has not occurred at the expense of other East Asian economies. Rather, we have seen a change in the composition of exports: with China’s emergence as the world’s assembly plant, other economies in the region have transitioned from the export of finished manufactures to the export of components to China, where they are assembled, often for sale in extraregional markets. For years, Japan has been China’s largest source of imports.

In this new world economic order, access to production networks is critical for a substantial part of economic growth in the economies of the region. Previously, it may have been possible to find alternative suppliers of raw materials if interstate conflict interrupted relations with a traditional supplier. But in a world of commodity chains, where different components are often sourced from multiple countries within and outside the region (for instance, in Apple’s supply chain for the iPhone and other products), and marketing the product depends on access to the brand name and distribution networks of a company with a global presence, the potential damage to an economy that loses access to global networks because of its undertaking of interstate aggression is so much higher than in the past. In Richard Katz’s (2013) terminology, this is a world of “mutual assured production.” In one important recent illustration, even though trade and investment between Japan and China dropped in 2012 and 2013 following increased tensions, trade began to recover in 2014 as firms and governments alike sought to defuse the effects that unresolved conflicts were having on economic relations.

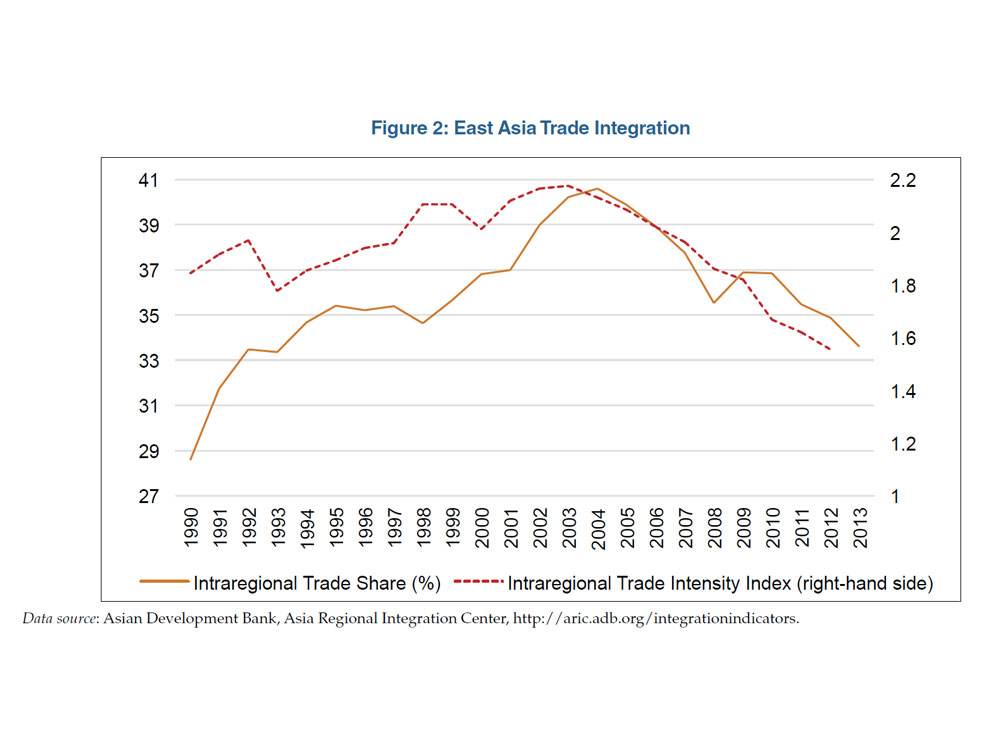

Despite the relatively rapid economic growth of almost all countries in the East Asian region, it is not, contrary to some arguments that gained popularity at the start of the global financial crisis, becoming “decoupled” from the global economy. Even though the extension of GVCs across East Asia has meant that there is arguably more “double-counting” of the value of intraregional exports in East Asia than anywhere else in the world, the share of intraregional trade in overall exports is no higher than it was 20 years ago (see Figure 2). Moreover, the trade intensity index, a more relevant indicator of the relative importance of intraregional trade (because it takes into account the relative weight of a region in global trade), shows a secular decline in this century. What we have seen is not a decoupling of East Asia from the global economy but a re-triangulation of trade as China has emerged as the largest market for other East Asian economies, assembling components that are then sent primarily to extraregional markets (Athukorala 2011). Asian economies depend, as never before, on their integration in the global economy.

Of course, economic “imperatives” have to be translated into policies in domestic political systems. The most persuasive argument on how changes at the global level are incorporated into domestic politics is found in the work of Etel Solingen (2003, 2007), who examines how coalitions favouring economic liberalization and internationalization have become the dominant political force in most countries in East Asia. The boundaries between the domestic and the international have become increasingly blurred. As Solingen (2014, 62) concludes: “the political power of internationalizing constituencies is unprecedented (though not irreversible), strengthened by intra-industry trade and integrated production chains.”

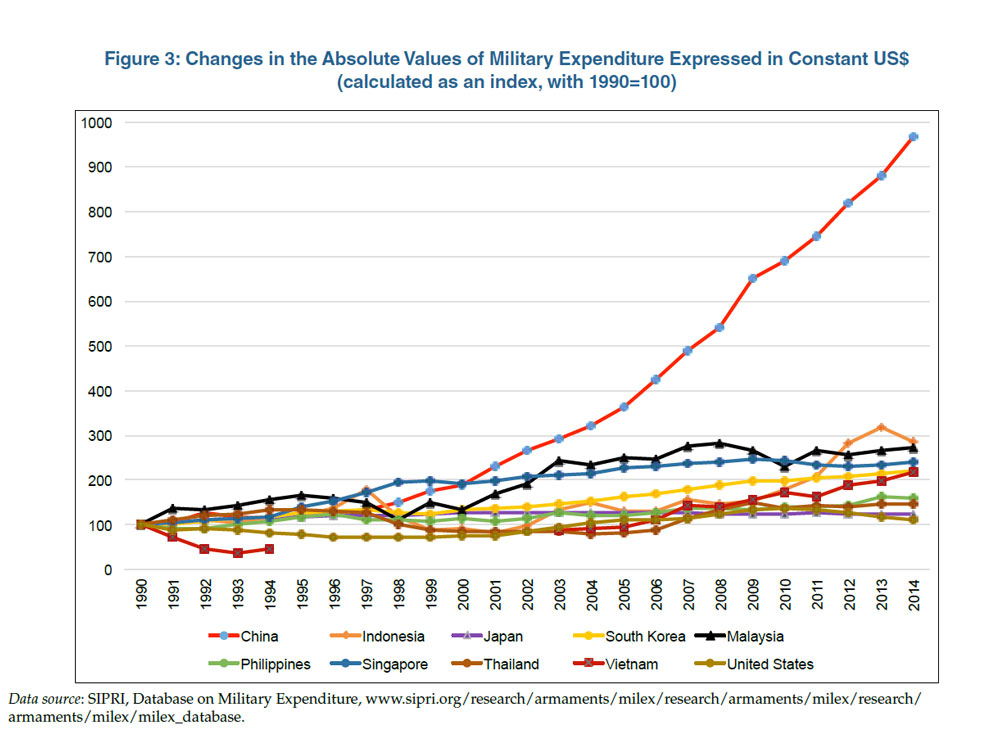

But is this altogether too sanguine a view of the impact of rapid economic growth on East Asia’s security context? Rapid economic growth also generates new challenges to regional stability. The most obvious link between economic growth and security comes through the opportunity that it provides to governments to increase military expenditure. The risk is that arms races will develop that not only waste scarce resources but that are also potentially destabilizing: historically, they have been associated with increased interstate tensions, poor decision making during crises and, in some circumstances, with a rise in interstate conflict (Rider, Findley, and Diehl 2011). Growth in naval capabilities in East Asia has illustrated some of the dangers of an arms race. We have seen a growth in the number of incidents involving vessels from countries in the region. Governments are increasingly concerned about the possibility that their neighbours are acquiring the capacity to disrupt sea lanes through which over half of the world’s merchant fleet (by tonnage) passes each year. A multilateral solution to sea-lane security in the region has not been agreed to.

Much has been written in recent years about an evolving arms race in the Asia-Pacific region, fuelled by the substantial expansion of Chinese military expenditure. Beijing is now the world’s second-biggest spender on the military, accounting for 10 percent of the global total: its spending has risen tenfold in the last quarter of a century, measured in constant dollars. Unconstrained by any arms control agreements, other countries have followed suit. Indonesia’s military budget increased by 350 percent in the decade after 2003 as it pursued an ambitious modernization program including the acquisition of submarines from South Korea, new multi-role jet fighters from Russia, antiship missiles from China and tanks from Germany and the United Kingdom.

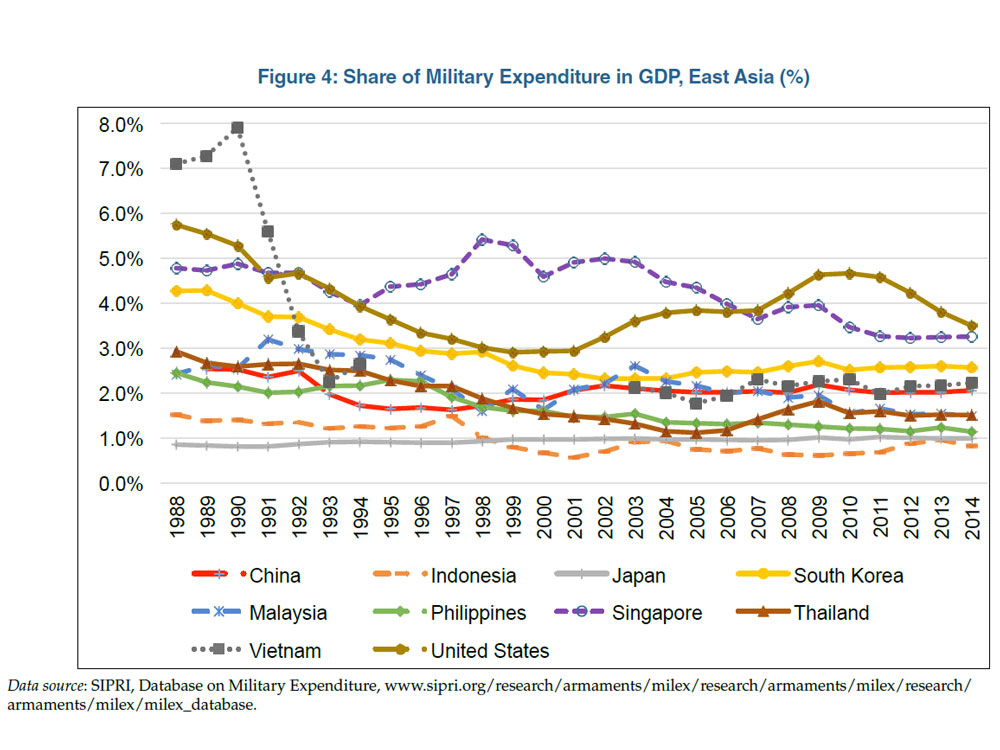

Aggregate data on growing military expenditures in the region, albeit alarming in themselves, do not tell the whole story. In most countries, military spending has not kept pace with rising GDP. Japan is the notable exception — albeit at one percent, has the lowest share of GDP devoted to military expenditure among East Asian countries (see Figure 3). Indeed, in most of East Asia, the share of GDP devoted to military expenditure has declined substantially over the last quarter of a century. From a glass half-full perspective, the situation would be much worse if military expenditures had kept pace with economic growth across the region. SIPRI estimates that China’s total military expenditure is still only one-third of that of the United States (although four times that of Japan).

Rapid economic growth poses security challenges in another domain: the increasing demand for natural resources that has followed directly from the region’s economic success. China has moved quickly, for instance, from being a significant oil exporter in the first half of the 1990s to being the world’s largest oil importer. Concerns at growing dependence on imported raw materials, exacerbated by fears that others are seeking to lock up or deny available supplies (for example, Malaysian threats to cut off Singapore’s water), has led to a redefinition of national understandings of security by state elites across the region (generating ideas of “comprehensive security”). Where national boundaries are poorly defined or disputed, the potential for conflict over resources is greater.

Nowhere is the linkage between resource issues and security more obvious than in the tensions over the SCS. According to the US Energy Information Administration (2013), the SCS holds proven oil reserves of at least 11 billion barrels and an estimated 190 trillion cubic feet of natural gas, similar to the proven oil reserves of Mexico, and two-thirds of the proven gas reserves of Europe (excluding Russia). Most of these reserves lie in uncontested territories, however. Arguably more significant are the fishery resources: the SCS is one of the most biologically diverse maritime areas in the world, containing nearly 10 percent of the fisheries used for human consumption worldwide (Rogers 2012). ASEAN members Brunei, Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines and Vietnam, as well as China, all have overlapping territorial claims in the SCS based on their exclusive economic zones established by the 1982 UN Convention on the Law of the Sea.

Competition over scarce natural resources need not inevitably lead to interstate conflict. China’s state-owned company, China National Petroleum Corporation, for instance, created a joint venture with the Indian state oil firm, Oil and Natural Gas Corporation, to acquire stakes in Syrian oil and gas properties. Australia and East Timor negotiated two treaties (2002 and 2007) that paved the way for the joint development of the Bayu-Undan gas and oil fields, even though the maritime boundary is still not agreed. To date, however, the SCS disputes have proved particularly intractable. China denies that the Permanent Court of Arbitration of the United Nations has jurisdiction in territorial disputes in the SCS. The settlement of China and Vietnam’s land boundary disputes did not spill over to maritime boundaries. Countries have been unwilling to submit disputes to international arbitration. And the plethora of regional institutions devoted to cooperation on natural resources have achieved little more than an exchange of information among their members (Ravenhill 2013).

While security concerns are normally thought of as arising from growing interdependence in terms of a cut-off of raw materials, globalization has increased states’ vulnerabilities to transnational disruptions to their economies in other areas — from both illicit and licit flows — as was seen in the devastating consequences of the withdrawal of foreign capital from the region during the 1997-1998 Asian financial crisis. Externally induced economic turmoil to date, however, has not led to increased interstate tensions within the region. Rather, it has had the opposite effect, contributing to enhanced intergovernmental collaboration on economic issues, most notably through the creation of a regional reserve pool, the Chiang Mai Initiative Multilateralized (Grimes 2014).

CONCLUSION

In early 2016, East Asia appeared to be facing the most unsettled security environment that it had experienced for a quarter of a century. Many of the dire warnings issued in the early 1990s by writers in the realist tradition appeared to be materializing. China was acting in an increasingly assertive manner on territorial issues; its hugely expanded military budget was stimulating a nascent arms race in the region. The Abe government was unwinding the constitutional restrictions on the deployment of Japanese military forces. Meanwhile, the North Korean regime continued to perceive that its interests lay in (predictably) unpredictable and uncooperative behaviour.

What prospects do the arguments from the three theoretical perspectives offer for ameliorating heightened security tensions in the region? The US “pivot” to Asia has brought Washington — and encouraged its Asian allies — into a much more direct policy of balancing against China than in the past. Although this appeared to bring some reassurance in the short term, the medium-term consequences of the policy are unclear. Several states in the region have been clearly alarmed by policies, both in the security and economic realms, that appeared to engage Washington in an increasingly direct confrontation with China. One dimension of the enhanced alliance system — an expanded international role for the Japanese military — worried some states, including a key US ally, South Korea. The possibility that the US pivot will not outlast the Obama administration — to be replaced either by an isolationist stance or by a less carefully calibrated confrontation of China — provides little comfort to regional states.

Meanwhile, regional institutions, despite growing in numbers, were seemingly incapable of effectively addressing the new security challenges. A need for better leadership and initiatives was evident, both within ASEAN and in the broader regional context. Here there are obvious opportunities for Indonesia — the natural leader within ASEAN as it is by far the grouping’s most populous state and its largest economy (accounting for more than one-third of both regional totals). For all of its weaknesses, ASEAN remains the regional institution best placed to attempt to broker relations between China and its regional neighbours.

Canada, too, as a country that is not directly “in” but is a part of the region, has the potential to play a constructive role. Despite its distance and its “absence” from regional diplomacy for most of this century, it still enjoys the legacy of goodwill built up from the 1990s when it promoted “track 1.5” approaches to sensitive security issues. At relatively low cost, it could assist in confidence-building efforts in the region. Moreover, by signing a bilateral trade agreement with China, Ottawa can signal that it does not regard the TPP as an instrument for the economic encirclement of the People’s Republic.

For liberals, enhanced economic interdependence is the ultimate guarantee of regional peace. Recent developments in the region and elsewhere, however, illustrate the challenges of using economic interdependence as a lever over unwelcome state behaviour. China’s increasing economic preponderance gives it leverage to split regional coalitions by buying off individual states — seen most vividly in Cambodia’s support for China’s approach to the SCS issue despite the opposition of most of its fellow members in ASEAN. A clear distinction needs to be drawn between the effects of economic interdependence in the aggregate on the one hand, and individual bilateral relationships on the other. As Albert Hirschman (1980) observed in one of the classics of the literature of global political economy, where extreme asymmetries in interdependence develop (in the case he studied, between Nazi Germany and the small states of central Europe) then weaker states have few options but to follow the policy preferences of the dominant power. Taiwanese governments have long feared that they would be placed in this position; China’s growth has caused others in the region to share this concern. China has not shied away from using economic leverage against governments whose policies have antagonized it — see, for instance, Angus Grigg and Lisa Murray (2015) for discussion of an Australian case. Elsewhere, the seeming ineffectiveness of sanctions in changing Russian behaviour toward Ukraine — and the vulnerabilities of European economies that have been revealed — indicate the difficulties of deploying economic interdependence as a weapon in security disputes.

Notes[1] “East Asia” in this paper refers to the 10 countries of ASEAN (Brunei, Cambodia, Indonesia, Laos, Malaysia, Myanmar, the Philippines, Singapore, Thailand and Vietnam) plus China, Japan, Korea and Taiwan. The arbitrariness of regional boundaries is particularly evident in the discussion of security issues: in this domain, East Asian boundaries are extremely permeable — and elastic.

Works cited:

Acharya, Amitav. 2001. Constructing a Security Community in Southeast Asia: ASEAN and the Problem of Regional Order. Politics in Asia Series. London: Routledge.

———. 2013. “ASEAN 2030: Challenges of Building a Mature Political and Security Community.” Asian Development Bank Institute, Working Paper 441. Tokyo. external pagewww.adbi.org/working-paper/2013/10/28/5917. asean.2030.political.security.community/call_made.

Athukorala, Prema-chandra. 2011. “Production Networks and Trade Patterns in East Asia: Regionalization or Globalization?” Asian Economic Papers 10 (1): 65–95.

———. 2014. “Global Production Sharing and Trade Patterns in East Asia.” In The Economics of the Pacific Rim, edited by Inderjit Kaur and Nirvika Singh. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Ba, Alice D. 2009. (Re)Negotiating East and Southeast Asia: Region, Regionalism, and the Association of Southeast Asian Nations. Studies in Asian Security. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Baldwin, Richard. 2011. “Trade and Industrialisation after Globalisation’s 2nd Unbundling: How Building and Joining a Supply Chain Are Different and Why It Matters.” Graduate Institute. Geneva.

Buzan, Barry, and Ole Waever. 2003. Regions and Powers: The Structure of International Security. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Calder, Kent E. 2004. “Securing Security through Prosperity: The San Francisco System in Comparative Perspective.” The Pacific Review 17 (1): 135–57.

Campbell, Kurt M., Nirav Patel, and Vikram J. Singh. 2008. The Power of Balance: America in Asia. Washington, DC: Center for a New American Security.

Dibb, Paul. 2002. “No Collective Security: Peace Looks Fragile in Asia.” The New York Times, June 19. www.nytimes.com/2002/06/19/opinion/19ihtedpaul_ ed3_.html.

Emmers, Ralf. 2003. Cooperative Security and the Balance of Power in ASEAN and the ARF, Politics in Asia Series. London: Routledge.

Fravel, M. Taylor. 2014. “Territorial and Maritime Disputes in Asia.” In Oxford Handbook of the International Relations of Asia, edited by Saadia M. Pekkanen, John Ravenhill and Rosemary Foot, 524–46. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Friedberg, Aaron L. 1993. “Ripe for Rivalry: Prospects for Peace in a Multipolar Asia.” International Security 18 (3): 5–33.

Gilpin, Robert. 1981. War and Change in World Politics. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Grigg, Angus, and Lisa Murray. 2015. “China Using Brazil Resources as Lever against Australia.” Australian Financial Review, May 25. www.afr.com/business/ mining/china-using-brazil-resources-as-lever-againstaustralia- 20150525-gh93de.

Grimes, William W. 2014. “The Rise of Financial Cooperation in Asia.” In Oxford Handbook of the International Relations of Asia, edited by Saadia M. Pekkanen, John Ravenhill and Rosemary Foot, 285–305. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Hirschman, Albert O. 1980. National Power and the Structure of Foreign Trade. The Politics of the International Economy, vol. 1. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Kang, David C. 2003a. “Getting Asia Wrong: The Need for New Analytical Frameworks.” International Security 27 (4): 57–85. Kang, David C. 2003b. “Hierarchy and Stability in Asian International Relations.” In International Relations Theory and the Asia-Pacific, edited by G. John Ikenberry and Michael Mastanduno, 163–89. New York, NY: Columbia University Press.

Katz, Richard. 2013. “Mutual Assured Production: Why Trade Will Limit Conflict between China and Japan.” Foreign Affairs, July/August.

Katzenstein, Peter J. and Rudra Sil. 2004. “Rethinking Asian Security: A Case for Analytical Eclecticism.” In Rethinking Security in East Asia: Identity, Power, and Efficiency, edited by Chae-jŏng Sŏ, Peter J. Katzenstein and Allen Carlson, 1–33. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Khong, Yuen Foong, and Helen E. S. Nesadurai. 2007. “Hanging Together, Institutional Design, and Cooperation in Southeast Asia: Afta and the ARF.” In Crafting Cooperation: Regional International Institutions in Comparative Perspective, edited by Amitav Acharya and Alastair Iain Johnston, 32–82. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Koopman, Robert, William Powers, Zhi Wang, and Shang- Jin Wei. 2010. “Give Credit Where Credit Is Due: Tracing Value Added in Global Production Chains.” National Bureau of Economic Research, Working Paper 16426. Cambridge, MA: NBER. www.nber.org/papers/ w16426.pdf.

Kurlantzick, Joshua. 2007. Charm Offensive: How China’s Soft Power Is Transforming the World. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Mastanduno, Michael. 2003. “Incomplete Hegemony: The United States and Security Order in Asia.” In Asian Security Order: Instrumental and Normative Features, edited by Muthiah Alagappa, 141–70. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Organski, A. F. K. 1958. World Politics. New York, NY: Knopf. Ravenhill, John. 2013. “Resource Insecurity and International Institutions in the Asia-Pacific Region.” The Pacific Review 26 (1): 39–64.

———. 2014. “Production Networks and Asia’s International Relations.” In Oxford Handbook of the International Relations of Asia, edited by Saadia M. Pekkanen, John Ravenhill and Rosemary Foot, 348–68. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Rider, Toby J., Michael G. Findley, and Paul F. Diehl. 2011. “Just Part of the Game? Arms Races, Rivalry, and War.” Journal of Peace Research 48 (1): 85–100.

Rogers, Will. 2012. “The Role of Natural Resources in the South China Seas.” In Cooperation from Strength: The United States, China and the South China Sea, edited by Patrick M. Cronin, 83–98. Washington, DC: Center for a New American Security.

SIPRI. 2015. “Trends in World Military Expenditure, 2014.” SIPRI Fact Sheet. Stockholm. http://books.sipri.org/ files/FS/SIPRIFS1504.pdf.

Smith, Anthony. 1999. “Indonesia’s Role in ASEAN: The End of Leadership?” Contemporary Southeast Asia 21 (2): 238–60.

Solingen, Etel. 2003. “Internationalization, Coalitions, and Regional Conflict and Cooperation.” In Economic Interdependence and International Conflict: New Perspectives on an Enduring Debate, edited by Edward D. Mansfield and Brian M. Pollins, 60–85. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press.

———. 2007. “Pax Asiatica Versus Bella Levantina: The Foundations of War and Peace in East Asia and the Middle East.” American Political Science Review 101 (4): 757–80.

———. 2014. “Domestic Coalitions, Internationalization and War: Then and Now.” International Security 39 (1): 44–70.

Sothanarith, Kong. 2015. “Cambodia Publicly Endorses China Position on South China Sea.” Voice of America, March 25. www.voanews.com/ articleprintview/2694301.html.

The Economist . 2012. “Divided We Stagger: Can Indonesia Heal the Deepening Rifts in South-East Asia?” The Economist, August 18. www.economist.com/ node/21560585/print.

Tow, William T. 2009. “Setting the Context.” In Security Politics in the Asia-Pacific: A Regional-Global Nexus?, edited by William T. Tow, 1–28. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

UNCTAD. 2013a. “Global Value Chains and Development: Investment and Value Added Trade in the Global Economy.” UNCTAD/DIAE/2013/1. Geneva: UNCTAD. http://unctad.org/en/ PublicationsLibrary/diae2013d1_en.pdf.

———. 2013b. World Investment Report 2013: Global Value Chains: Investment and Trade for Development. New York and Geneva: United Nations.

US Energy Information Administration. 2013. “Contested areas of South China Sea likely have few conventional oil and gas resources.” April 3. www.eia.gov/ todayinenergy/detail.cfm?id=10651.

White, Hugh. 2012. The China Choice: Why America Should Share Power. Carlton, Australia: Black Inc.

World Bank. 2014. “East Asia Pacific Economic Update, October 2014 — Enhancing Competitiveness in an Uncertain World.” Washington, DC: World Bank. www.worldbank.org/content/dam/Worldbank/ document/EAP/region/eap-economic-updateoctober- 2014.pdf.

WTO. 2010. “Lamy Says More and More Products Are ‘Made in the World.’” WTO. www.wto.org/english/ news_e/sppl_e/sppl174_e.htm.