Conflict Recurrence

26 Dec 2016

By Scott Gates, Håvard Mokleiv Nygård, and Esther Trappeniers for Peace Research Institute Oslo (PRIO)

This article was external pageoriginally publishedcall_made by the external pagePeace Research Institute Oslo (PRIO)call_made in Conflict Trends 02/2016.

The seeds of war are often sown during war. Violence associated with armed conflict adds more grievances to those that led to conflict in the first place. Of the 259 armed conflicts identified by the Uppsala Conflict Data Program (UCDP), 159 recurred and 100 involved a new group or incompatibility. 135 different countries have experienced conflict recurrence, and the pattern is deepening. Recurring conflict is symptomatic of unaddressed grievances, and lasting peace will not be achieved until these issues are addressed. Peace agreements guaranteed by peacekeepers are much more likely to prevent wars from recurring in the years immediately following war. In the long- run, political reforms are necessary to ensure durable peace.

Brief Points

- War begets war.

- 60% of all conflicts recur.

- On average, post-conflict peace lasts only seven years.

- Since the mid 1990s, most conflict onsets have been recurrences.

- Peace agreements lay the groundwork for stable peace.

- Political reforms are necessary to achieve lasting peace.

War Begets War

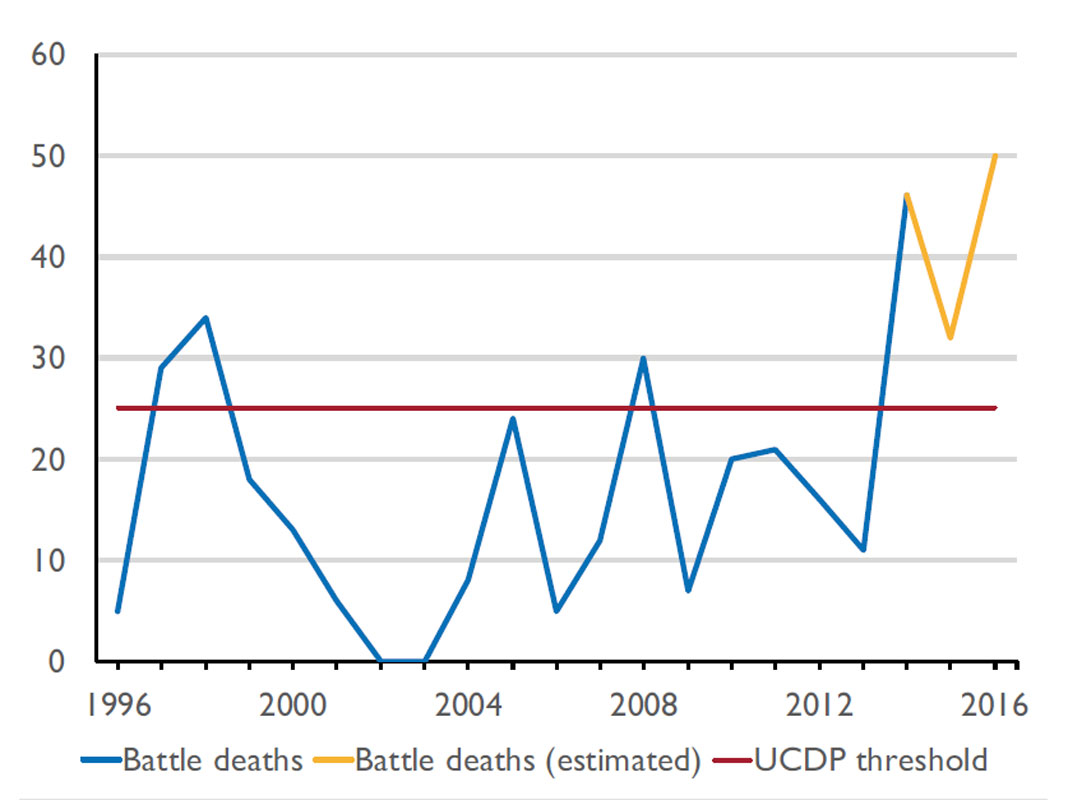

On the 2nd of April 2016, the “frozen conflict” in Nagorno-Karabakh, a disputed enclave between Armenia and Azerbaijan, heated up again. In four days over 50 people were killed, as helicopters, tanks, and artillery were brought back into action. For 21 years, low-level conflict has intermittently flared up (see Figure 1). The issues underlying the conflict have never truly been resolved.

In 1988, Nagorno-Karabakh voted to secede from then-Soviet Azerbaijan and join Armenia, and with the Soviet Union collapsing, a bloody war broke out over the territory. ‘Some 30,000 were killed and hundreds of thousands displaced before a 1994 ceasefire halted the combat. Armenian forces took Nagorno-Karabakh and several surrounding regions, leaving Azerbaijan around 15% smaller’ (The Economist, 15 April 2016: external pagewww.economist.com/blogs/economist- explains/2016/04/economist-explains-9call_made). A Russian brokered ceasefire on the 5th of April is holding for now, but escalation to war is a real possibility. Even worse, the conflict could become regionalized with global significance. Russia has a military base in Armenia and is obligated by treaty to defend it, while Turkey backs its ethnic brethren in Azerbaijan.

Figure 1: Battle deaths in Nagorno-Karabakh conflict

Time has not healed the wounds of the war. Since the ceasefire of 1994, political leaders in both countries have marshalled nationalist narratives to consolidate power. Military expenditures have risen, arms procurements grown, and domestic arms production industries developed.

Over the past two years, both economies have been suffering. The conflict in many ways serves as a diversion. There is little interest in addressing fundamental issues fuelling the conflict. Moreover, every outbreak of violence opens up new wounds and hardens grievances.

War begets war. Latent and manifest conflicts stem from unresolved issues of contention. Festering grievances and opportunism lay the groundwork for conflict recurrence and the threat of escalation.

Trends in Conflict Recurrence

The Uppsala Conflict Data Program (UCDP), the leading provider of statistics on political violence, has identified 259 distinct armed conflicts since 1946. This includes all organized military conflict over government or territory involving one or more state government(s) and causing at least 25 battle-related fatalities in a year. Several conflicts may take place in a single country, involving different sets of actors engaged in a deadly contest with the state.

Of these 259 conflicts, 159 recurred and 100 involved a new group or incompatibility. 135 different countries experienced conflict recurrence. 68 were minor conflicts and 24 were wars. Around 60% of conflicts recur. The median duration of post-conflict peace spells was seven years.

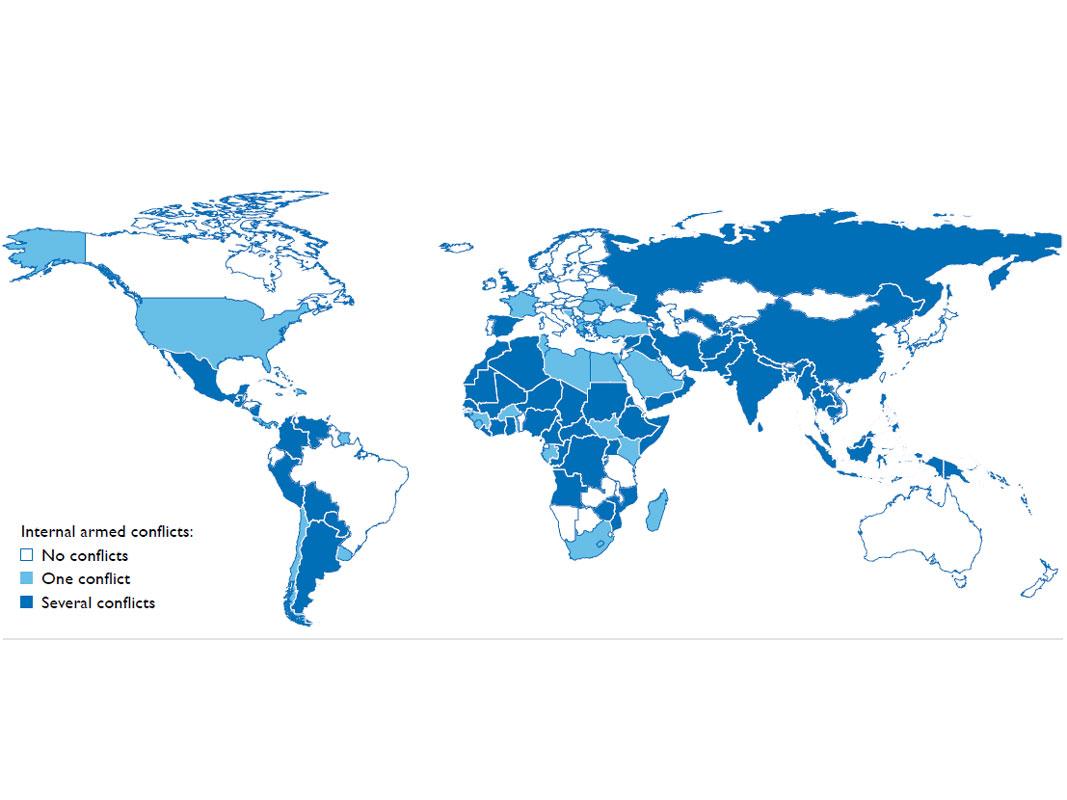

The map in Figure 2 shows three categories of countries; those who have never seen conflict as defined by UCDP, those that have had only one conflict, and those that have experienced conflict recurrence. As the map shows, most countries have experienced recurrence of armed civil conflict since 1946. The Nagorno-Karabakh conflict serves as a good example of conflict that is never resolved.

Figure 2: Conflict recurrence across the world

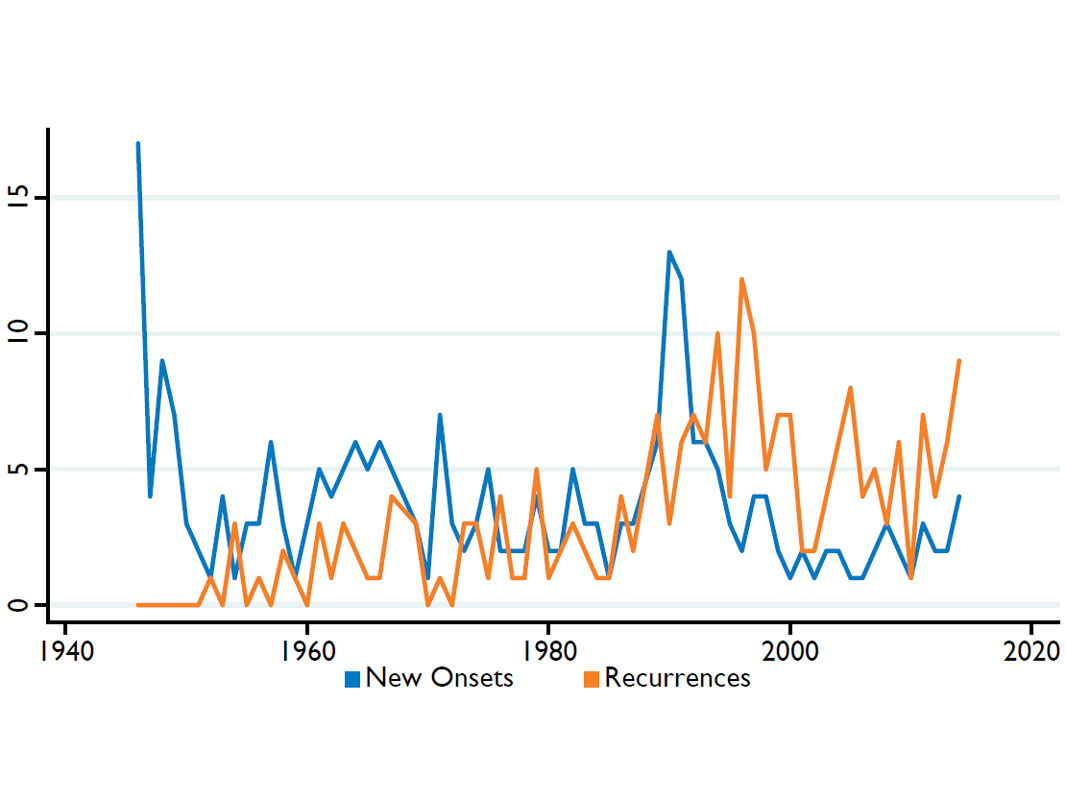

Since the mid-1990s, conflict recurrence has been more common than the onset of new conflict (see Figure 3). Before 1970, most conflicts were new. Decolonialization and the breakup of the Soviet Union is associated with a strong increase in the onset of new conflicts. The early 2000s witnessed the lowest number of new conflict onsets on record. Since then, the number of new conflict onsets has increased slightly. Alarmingly, the number of recurring conflicts has risen precipitously.

Figure 3: New and recurring conflicts globally, 1946–2014

Regional Trends

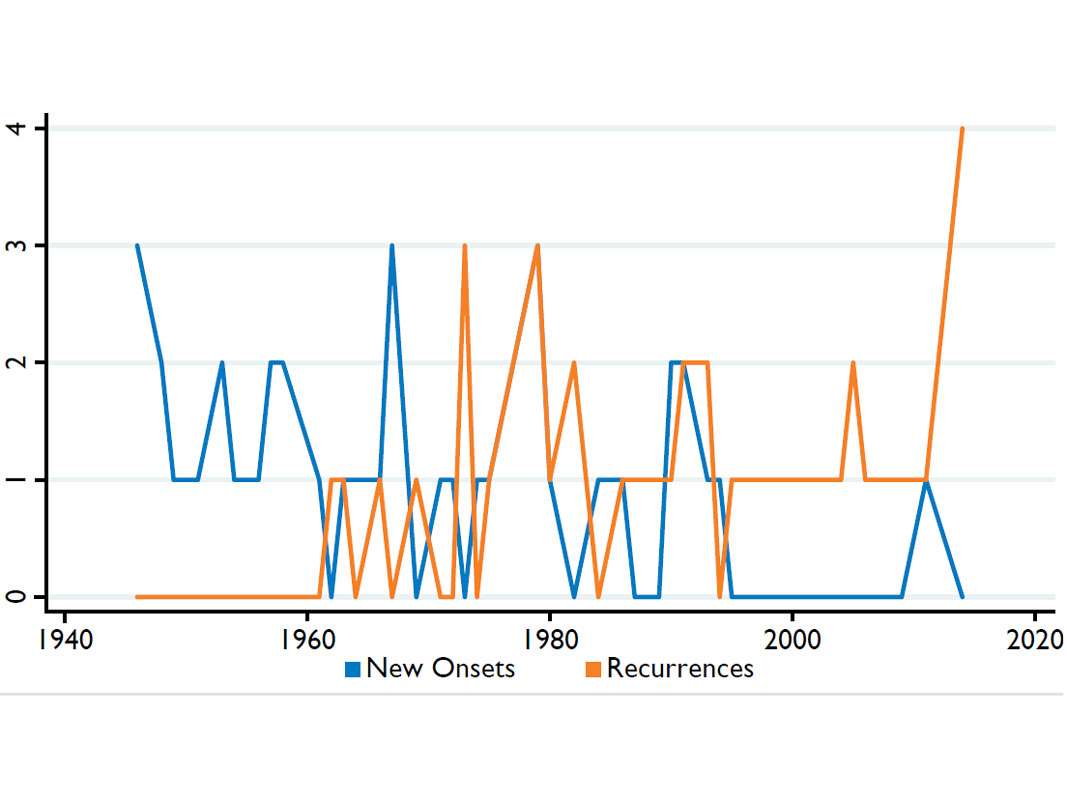

Two regions in particular account for the rise in conflict recurrence, the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) and Sub-Saharan Africa. Figure 4 shows conflict recurrence spiking in the MENA region following the Arab Spring. Indeed, the Arab Spring did not lead to new conflicts, but ignited latent conflicts.

Good news comes from other regions. Since the 1990s, Latin America has seen fewer and fewer new conflicts and more importantly, the end to cycles of conflict recurrence. Understanding how peace spread in Latin America helps us understand broad patterns of conflict recurrence.

Figure 4: New and recurring conflicts, MENA

Why Conflicts Recur

Previous research has identified a set of explanations as to why conflict recurs; conflicts between different ethnic groups strengthen di visions and hatred and make durable peace less likely; poor and underdeveloped countries are more likely to see conflict resumption because groups opposing the state have little to lose; lack of democracy prevents peaceful resolution of conflict; settlements without a clear victory create incentives to continue fighting to improve one’s position; and a lack of a security guarantee provokes resumption as a means to avoid marginalization by antagonistic groups. Lastly, natural resources have been shown to be related to conflict recurrence by exasperating grievances, providing a means of financing rebellion, and increasing the value of controlling the state.

This research, however, ignores the effect of war itself. Indeed, the seeds of war are often sown during war. Atrocities associated with the violence of armed conflict create grievances. Unresolved grievances can fester during periods of low-level and latent conflict. Failing to address this underlying dynamic leads to a pattern of conflict recurrence.

The Conflict Trap

The consequences of conflict are not confined to the duration of the conflict and its immediate aftermath. The consequences of conflict persist long after the conflict has ended. Indeed, low levels of socio-economic development are important causes of conflict in the first place. Low levels of socio-economic development inhibit the building of stable and strong political institutions capable of mediating and quelling conflict efficiently. Low levels of development, and especially a lack of employment opportunities, also make joining rebellion relatively less costly. In addition, the lack of economic development can be an important grievance motivating individuals to join rebel organizations.

While the direct consequences of conflict are detrimental, the indirect consequences are even greater. Conflict is “development in reverse”. The consequences of conflict we document are liable to capture countries in what Paul Collier labelled the “conflict trap”. This trap represents a vicious circle where low levels of development lead to conflict and conflict leads to even lower levels of development. The actual total cost of conflict is therefore likely to be much higher than the conservative estimates we present here. Indeed, so far we have only discussed the effect of a median intensity conflict. Recent conflicts, such as the ones in Syria and Iraq, have much higher intensity levels. We find that more intensive fighting leads to much longer recovery times.

It should also be noted that many of the consequences of armed conflict have never been measured, and some are not even measurable. Among those not incorporated in our analysis is the increased number of young males with war experience; the accumulation of light weapons subsequently used in violent crime; the psychological impact of traumatic experiences; and erosion of trust and emergence of ethnic prejudice.

Another burden not easily measured is the environmental impact of war. Few indicators allow a systematic comparison of this burden. We show the detrimental effect of conflict on the accessibility of water and adequate sanitation facilities, which are indicators with a considerable environmental component.

Some consequences of conflict are highly context specific. In countries such as Cambodia and Liberia, conflict set the stage for large-scale illegal logging; in other places, other aspects of environmental regulation break down; and elsewhere, unexploded ordinances are a major problem caused by armed conflict.

The Role of the International Community, Peace Agreements, and Conflict Recurrence

Peace agreements fundamentally involve the belligerent parties to the conflict. Both parties sign when peace is more attractive than conflict. This may take a while; the parties may have to endure the cost of conflict for some time before peace seems ripe.

A central problem plaguing all peace agreements is the commitment problem. In contrast to conflicts that end with a clear victor, negotiated settlements create incentives to work to take advantage of the other party. This creates a security dilemma. The incentive for both parties is to prepare for future conflict and not to invest in peace.

One way of addressing the commitment problem is through the deployment of peacekeepers. Following the 1994 ceasefire between Azerbaijan and Armenia, no peacekeepers were deployed. The international community largely left the warring parties to their own devices. Peacekeeping works. The more the UN is willing to spend on peacekeeping, and the stronger the mandates provided, the greater the conflict-reducing effect.

Research has shown that the risk of conflict recurrence drops by as much as 75% in countries where UN peacekeepers are deployed. Peacekeepers can mediate the risk of conflict recurrence in the short and medium term, but to achieve lasting peace the fundamental grievances must be addressed.

The commitment problem is especially serious in the cases of civil wars. In the wake of conflict, demobilization and disarmament of the rebels’ army tips the advantage towards the state. In many cases the state becomes increasingly exclusive if not repressive, fuelling resentment and grievances.

Political institutions that safeguard against government repression and limit the extent of economic and political exclusion serve to provide a more enduring peace. These institutions need to be constitutional and firmly entrenched. Other aspects of governance are also important for building peace. Good governance is more than democracy. It limits corrupt and nepotistic bureaucracies, enshrines the rule of law, implements economic policies that promote growth and stability, prohibits military influence over politics, and protects vulnerable populations from exclusion. Good governance need not address every one of these aspects at once, but success in one area or a couple will spill over into other domains.

Peace in the short run is more easily built under the auspices of peace agreements guaranteed by peacekeepers. In the long run, political reforms are necessary to ensure durable peace. Recurring conflict is symptomatic of unaddressed grievances. Lasting peace will not be achieved until unresolved conflict is addressed.

What is conflict recurrence?

UCDP defines three states of armed conflict, including: ‘no conflict’ or less than 25 battle-related deaths reported in a year; ‘minor conflict’ or between 25 and 999 battle-related deaths per year; and ‘major conflict’, which occurs when more than 1000 battle-related deaths per year are reported.

Differentiating conflict recurrence from on-going conflict is not so straightforward. It depends on how one determines the beginning and end to an armed conflict. In cases of complete victory or the signing of a peace agreement, the determination of the end of conflict is relatively clear. A period of armed conflict is followed by a significant period of peace. Short interludes of a couple of months between periods of fighting, in contrast, are clearly cases of continued conflict.

The conventional practice among researchers is to apply a ‘two-year rule’. Two years of peace constitutes the end of a conflict. If the fighting resumes after less than two years, the conflict is defined as on- going. If a conflict starts again after a two-year period of no conflict, the conflict has recurred. We relax this two-year rule and also employ a five- and ten-year rule.

The key point is that the parties that had been involved in the first war are the same parties that fight in the second or third or fourth war. Such cases are considered to be ‘recurring conflict’. A conflict involving a new actor(s) fighting the state is regarded to be ‘new conflict’.

Peace entails more than the absence of conflict and it certainly means more than falling below a threshold of 25 battle deaths. Recurring conflict is a sign that latent conflict has not been properly resolved. This is illustrated in Figure 1. The red line shows UCDP’s threshold for categorizing a minor conflict. Many outbreaks of violence fail to cross the threshold. Conflict recurrence even below 25 battle deaths is nevertheless an indication of latent conflict and arrested peace. The danger is that low level conflict can escalate and even cross the 1000 battle death threshold, or even worse.

About the Authors

Scott Gates is a research professor at PRIO and an editor of International Area Studies Review. Håvard Mokleiv Nygård is a PRIO senior researcher and a managing editor at International Area Studies Review. And, Esther Trappeniers is an intern at PRIO.

For more information on issues and events that shape our world, please visit the CSS Blog Network or browse our Digital Library.