The Trump Administration´s FY 2018 Defense Budget in Context

25 Aug 2017

By Katherine Blakeley for Center for Strategic and Budgetary Assessments (CSBA)

This article was external pageoriginally publishedcall_made by the external pageCenter for Strategic and Budgetary Assessments (CSBA)call_made on 3 August 2017.

Far From an Historic Increase

Strengthening the U.S. military was one of the key themes of Donald Trump’s presidential campaign. After saying that “our military is a disaster,” and “depleted,” he colorfully promised to make the U.S. armed forces “so big, so powerful, so strong, that nobody—absolutely nobody—is gonna mess with us.”1 Trump painted his plans in bold strokes: increasing the size of the Army to 540,000 soldiers; adding 20,000 Marines; bringing the Air Force to at least 1,200 combat aircraft; and increasing the Navy to a fleet of some 350 ships. Funding this force structure buildup would require roughly $200 billion more over five years than envisioned in the Obama administration’s 2017 defense plan. Getting just the Navy to its promised force structure of 355 ships would require an extra $5.5 billion annually over current shipbuilding funding.2 Achieving these force structure levels would require funding increases that are more than double the Trump administration’s proposal for $18.5 billion over the PB 2017 projections for FY 2018, or an additional $40 billion annually over the PB 2017 Future Years Defense Program (FYDP).3

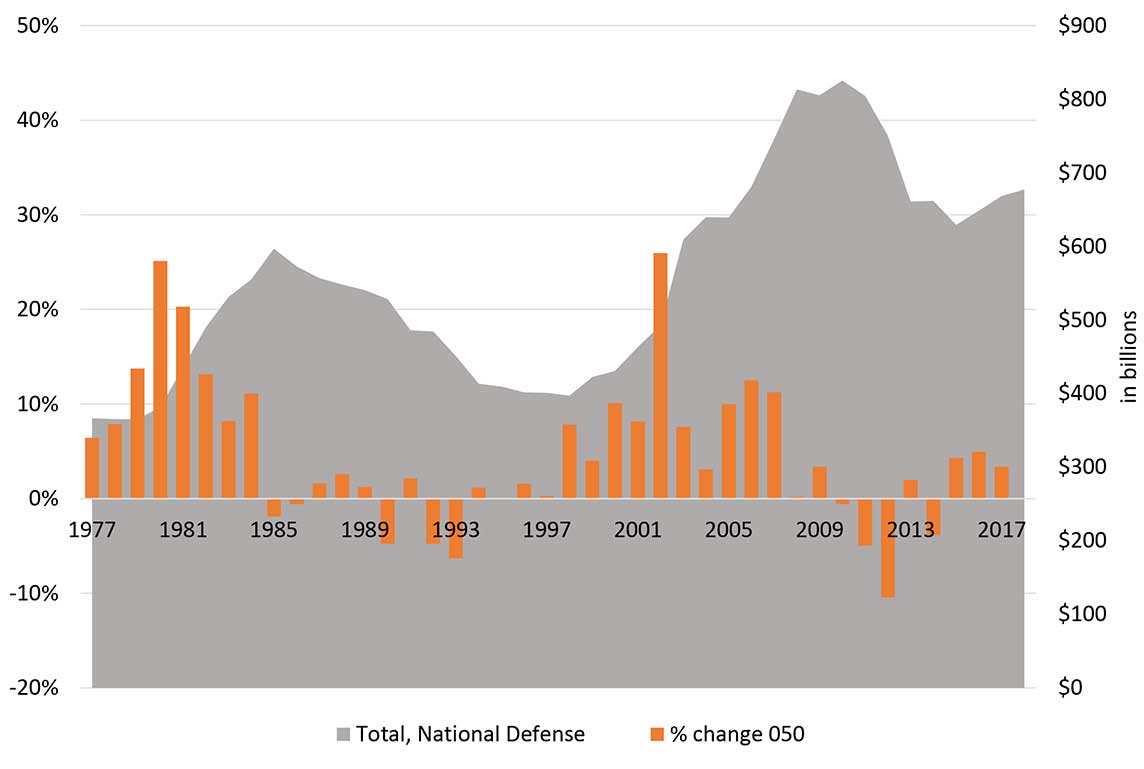

President Trump painted his proposed $603 billion national defense budget as “historic,” focusing on the requested 9.4 percent increase over the Obama administration’s request for FY 2017 and 10 percent increase over the BCA caps for FY 2018.4 However, even against this more generous yardstick than the 3 percent increase over the $584.5 billion in national defense funding projected for FY 2018, the requested $603 billion is far short of an historic increase. There have been year-over-year increases in total national defense spending of 10 percent or more ten times between FY 1977 and FY 2017, largely during the Carter–Reagan buildup of the early 1980s and again during the ramping up to the Iraq war in the early 2000s (see Figure 2-1).

Figure 2-1: Year-Over-Year in 050 National Defense Spending, FY77–FY18

Source: OMB, Historical Tables, Budget of the United States Government, Fiscal Year 2018 (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 2017), Table 5.1, “Budget Authority by Function and Subfunction: 1976–2022,” available at https://www.whitehouse.gov/sites/whitehouse.gov/files/omb/budget/fy2018/hist05z2.xls.

Note: This figure presents total 050 national defense spending, including both base and OCO spending, in FY 2018 dollars. The year-over-year figures are calculated using current-year dollars to maintain consistency with President Trump’s point of comparison.

President’s Budget Roadblocks to a Defense Buildup

National security is an afterthought in the FY 2018 President’s Budget request, playing fourth fiddle to tax cuts, cutting non-defense discretionary spending by 30 percent over a decade to a record low of 1.4 percent of GDP, and balancing the federal budget within ten years.5 Instead of repealing the Budget Control Act caps on defense, as both Congressional Democrats and Republicans have called for, this budget would extend them six years through 2027. It does call for raising the defense caps by 2 percent annually, which would yield an additional $489 billion for national defense spending—but it offsets these raises with $1.6 trillion of deep cuts to non-defense discretionary spending that are unlikely to be enacted (see Figure 2-2 and Figure 2-3). Many of the cuts have drawn criticism from conservative Republicans like long-time appropriator Rep. Hal Rogers (R-KY), who said that he is “deeply concerned about the severity of the domestic cuts,” and the current chairman of the House Appropriations Committee Rep. Rodney Frelinghuysen (R-NJ), who emphasized that Congress retains “the power of the purse.”6 Many other Republican legislators whose votes the Trump administration would need have offered dim prospects for the budget’s survival in Congress and emphasized Congressional primacy in appropriations. Sen. John Cornyn (R-TX) said that “almost every president’s budget proposal that I know of is basically dead on arrival,” while Rep. Tim Scott (R-SC) characterized the PB 2018 request as “like a press release. I don’t think anyone is going to focus on the president’s budget to decide how we create our own budget.”7 Senate Budget Committee chairman Sen. Michael Enzi (R-WY) enjoined people from panicking: “They’re just suggestions.”8

Figure 2-2: Current and Proposed Caps in Defense and Non-Defense Discretionary Spending

Source: OMB, Budget of the U.S. Government, Fiscal Year 2018, “Summary Tables,” Table S-7, “Proposed Discretionary Caps for 2018 Budget,” in current-year dollars.

Figure 2-3: Proposed Changes to Defense and Non-Defense Discretionary Spending in PB18

Source: OMB, Budget of the U.S. Government, Fiscal Year 2018, “Summary Tables,” Table S-7, “Proposed Discretionary Caps for 2018 Budget,” in current-year dollars.

The FY 2018 President’s Budget also suggests phasing out the overseas contingency operations account, the “emergency supplemental” that has provided a substantial portion of the military’s recent funding. OCO funding would decline from $60 billion in FY 2018 to $10 billion in FY 2022. By giving with one hand and taking away with the other, the Trump administration’s PB 2018 budget would actually depress the overall level of national defense spending by $3 billion over five years—from $668 billion in 2018 to $665 billion in 2022 in current dollars. After adjusting for inflation, total national defense spending would fall by 2 percent annually in real terms over the next five years—from $668 billion in FY 2018 to $614.4 billion in FY 2022. Between FY 2022 and FY 2027, national defense spending would rise by 1 percent annually.9 By FY 2027, national defense spending would be $640.6 billion in FY 2018 dollars—$27.4 billion lower than the $668 billion requested in FY 2018 and equal to just 2.4 percent of GDP (see Figure 2-4).10

Figure 2-4: Proposed National Defense Base and Oco Spending FY18–FY22

Source: Office of Management and Budget, President’s Budget FY 2018, “Summary Budget Tables, Table S-7. Proposed Discretionary Caps for 2018 Budget.”

Note: in FY 2018 dollars.

Small-print footnotes in the 2018 budget request allow for a glimmer of hope, noting that the prospective defense budget numbers don’t reflect a policy judgment about the right level of defense spending.11 In a July 7 memo, Office of Management and Budget Director Mick Mulvaney directed federal agencies to submit proposed additional investments for up to a 5 percent overall budget increase.12 Unfortunately, the deficit-hawk orthodoxies embraced in the request are incompatible with a real-world–driven approach to defense spending. Any increases to defense spending above the flat levels penciled into the budget would require either further discretionary cuts or abandoning a balanced budget within ten years and embracing at least some measure of deficit spending—anathema to OMB Director Mulvaney and other GOP deficit hawks. A major decision point for President Trump looms: will his administration pursue higher levels of national defense spending in FY 2019 and beyond, even if it is not offset by non-defense discretionary cuts?

Where’s the CAGR?

The absence of any real defense buildup in the Trump administration’s PB 2018 is clear. After adjusting for inflation, the PB 2018 plan through FY 2022 grows base national defense spending to $605.2 billion—just $2.2 billion over the base budget request for $603 billion in FY 2018. This is a cumulative annual growth rate (CAGR) of just 1.2 percent above the $562.2 billion in base national defense funding requested by President Obama for FY 2017. If base national defense spending were to grow by 3–5 percent annually in real terms between FY 2017 and FY 2022, it would reach $670 to $755 billion in FY 2022 (in FY 2018 dollars). This is at or over the McCain–Thornberry proposed level of $684 billion in FY 2022, which would represent real growth of 3.3 percent annually. Factoring in OCO funding, total national defense funding would have to increase from President Obama’s FY 2017 level of $622.1 billion to between $740 billion and $835 billion in FY 2022 to reach a CAGR of 3–5 percent annually (see Table 2-1 and Figure 2-5).

Table 2-1: National Defense Funding CAGR From FY17 Request, Compared

Figure 2-5: Notional National Defense Spending Growth Rates

Across the FY 2018–FY 2022 FYDP, after adjusting for inflation, President Trump’s proposed base national defense funding is not only substantially below that proposed by Sen. McCain and Rep. Thornberry but also lower than the national defense funding levels agreed to by the House and Senate Republican caucus in the FY 2017 budget resolution as passed in January 2017. Across the five years of the PB18 FYDP, after adjusting for inflation, the Trump administration’s proposed base spending on national defense would total $3.02 trillion, some $291 billion lower than the $3.31 trillion total proposed by Sen. McCain and Rep. Thornberry. However, the Trump administration’s proposal for $3.02 trillion would be a cumulative $125.4 billion over the planned national defense funding levels from the Obama administration’s PB 2017 (see Figure 2-6).

After factoring in projected OCO spending, the Trump administration’s total national defense funding for FY 2018–FY 2022 would total $3.21 trillion in FY 2018 dollars, creating a gulf of $395 billion below the total of $3.6 trillion in overall national defense funding called for by Sen. McCain and Rep. Thornberry (see Figure 2-7).

Figure 2-6: FY18–FY22 Base National Defense Funding Plans

Figure 2-7: FY18–FY22 Total National Defense Funding Plans

Note: The FY 2012 FYDP includes a notional $50 billion OCO placeholder. The FY 2017 FYDP does not include any OCO placeholder. The second FY 2017 Budget Resolution includes zero OCO funding past FY 2017.

NOTES

1 Andrew Tilghman, “Donald Trump Paints a Dismal Picture of Today’s Military,” Military Times, October 3, 2016, available at http://www.militarytimes.com/articles/trump-paints-dismal-picture-of-todays-military; and Josh Eidelson and Dimitra Kessenides, “The Promises of President-Elect Donald Trump, in His Own Words,” Bloomberg Businessweek, November 10, 2016, available at https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2016-11-10/the-promises-of-president-elect-donald-trump-in-his-own-words.

2 Eric Labs, Costs of Building a 355-Ship Navy (Washington, DC: CBO, April 2017), p. 1, available at https://www.cbo.gov/system/files/115th-congress-2017-2018/reports/52632-355shipnavy.pdf.

3 This calculation is based on CSBA analysis utilizing CSBA’s proprietary Strategic Choices Tool to grow the force structure and associated capabilities to these proposed levels.

4 Steve Holland, “Trump Seeks ‘Historic’ U. S. Military Spending Boost, Domestic Cuts,” Reuters, February 28, 2017, available at http://www.reuters.com/article/us-usa-trump-budget-idUSKBN1661R2.

5 Gary Cohn, “President Trump Proposed a Massive Tax Cut. Here’s What You Need to Know,” The White House blog, April 26, 2017, available at https://www.whitehouse.gov/blog/2017/04/26/president-trump-proposed-massive-tax-cut-heres-what-you-need-know; and Office of Management and Budget (OMB), Budget of the U.S. Government, Fiscal Year 2018: A New Foundation for American Greatness (Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office [GPO], May 2017), “Summary Tables.”

6 Andrew Restuccia, Matthew Nussbaum, and Sarah Ferris, “Trump Releases Budget Hitting his Own Voters Hardest,” Politico, May 22, 2017, available at http://www.politico.com/story/2017/05/22/trump-budget-cut-social-programs-238696; and Rodney Frelinghuysen, Chairman of the House Appropriations Committee, “Statement on President’s Budget Request,” May 24, 2017, available at https://frelinghuysen.house.gov/top-news/chairman-frelinghuysen-statement-on-presidents-budget-request/.

7 Andrew Taylor and Martin Crutsinger, “Trump’s Proposed Federal Budget Calls for Deep Domestic Cuts,” Associated Press, May 22, 2017; and Susan Ferrechio, “GOP Spooked by Big Cuts in Trump’s Budget Plan,” The Washington Examiner, May 24, 2017, available at http://www.washingtonexaminer.com/gop-spooked-by-big-cuts-in-trumps-budget-plan/article/2623964.

8 Ryan McCrimmon, “Trump Budget Request Rolls Out to a Quarreling Congress,” Roll Call, May 23, 2017, available at http://www.rollcall.com/news/politics/first-trump-budget-request-rolls-quarreling-congress.

9 OMB, Budget of the U.S. Government, Fiscal Year 2018, “Summary Tables,” Table S-7, “Proposed Discretionary Caps for 2018 Budget.”

10 OMB, Budget of the U.S. Government, Fiscal Year 2018, “Summary Tables,” Table S-5, “Proposed Budget by Category as a Percent of GDP.”

11 OMB, Budget of the U.S. Government, Fiscal Year 2018, “Summary Tables,” Table S-7, “Proposed Discretionary Caps for 2018 Budget,” and p. 41.

12 Mick Mulvaney, Director, OMB, “Fiscal Year (FY) 2019 Budget Guidance,” Memorandum for the Heads of Departments and Agencies, M-17-28, July 7, 2017, available at https://www.whitehouse.gov/sites/whitehouse.gov/files/omb/memoranda/2017/M-17-28.pdf.

About the Author

Katherine Blakeley is a Research Fellow at the Center for Strategic and Budgetary Assessments. Prior to joining CSBA, Ms. Blakeley worked as a defense policy analyst at the Congressional Research Service and the Center for American Progress.

For more information on issues and events that shape our world, please visit the CSS Blog Network or browse our Digital Library.