Russian Analytical Digest No 184: Russian Food Policy

20 Jun 2016

By Robert W Orttung and Yevgenny Popravko for Center for Security Studies (CSS)

This issue of the Russian Analytical Digest was originally published by the Center for Security Studies (CSS) on 24 May 2016.

Feeding Russia

By Robert W. Orttung, Washington

Abstract

Russia’s current food policy has different impacts on different parts of the population. Some of the elites are benefitting enormously, while much of the population is facing increased pressure from higher prices and reduced choice. Despite growing discontent, the population’s resilient adaptive capacity suggests that little will change soon.

A Policy Like All Others

President Vladimir Putin’s food policy does not differ much from the rest of his policies. First, and most importantly, it supports a key handful of individual elites who are close to the president or have proved that they are useful for his system. In order to justify this outcome, the policy builds on the state narrative, relentlessly disseminated through the subordinate media, that the country is surrounded by hostile forces seeking to destroy Russia. Accordingly, a central objective of Putin’s food policy is to try to punish the Western countries that have imposed sanctions on Russia by blocking food imports from those countries. Putin’s counter-sanctions benefit domestic food companies that no longer have to compete against foreign producers.

Second, even though the population is beginning to feel some pain from the imposition of the president’s policies, the sources of change in society are weak. In democratic systems, economic pain usually takes a toll on the popularity of the country’s leaders, resulting eventually in the election of a new elite. While Russia has parliamentary elections planned for September 2016, all signs suggest that pro-Kremlin parties will maintain control of the legislature. As in all recent elections, most serious opposition candidates will not be allowed on the ballot. Finally, regardless of the growing power of the Russian elite and the deteriorating conditions for everyone else, there are sources of resiliency in Russian society which suggest that little is likely to change in the near future. Ordinary people will find ways to make do. But, by the same token, there is unlikely to be much social progress or economic development either.

Sanctions and Counter-Sanctions

The Western countries imposed economic sanctions on Russia following the annexation of Crimea through military force and the Kremlin’s subsequent backing of the insurgency in Ukraine’s Donbass. The Western sanctions were designed to be “smart” in the sense that they targeted individuals and companies directly involved in the occupation operations. In the case of the U.S., these sanctions followed logically from the sanctions imposed on specific individuals identified as being responsible for human rights violations in Russia as part of the Magnitsky List legislation adopted in 2012. Then punishments consisted of visa bans and asset freezes.

The smart sanctions were, in part, a response to the failure of comprehensive sanctions, including financial and trade embargoes, against Iraq in the 1990s. Those sanctions ended up hurting vulnerable members of the population. The smart sanctions, in contrast, were aimed at influencing the elite members of society who supported and benefited from the regime in power.

The sanctions had multiple purposes. While nobody expected Russia to buckle under pressure, part of the idea was to make the people closest to President Putin suffer so that they would potentially lobby the president to change his policies. Of course, the possibility that Putin would listen to such advisors or that they would feel comfortable speaking frankly is exceedingly small. Given that the conflict in Ukraine will play out over the long term, the sanctions sought to prevent Russian forces from advancing beyond Crimea and the eastern part of the Donbass. They also sought to shift the means of the conflict from purely military weapons to other levers, such as economic tools. And perhaps most importantly, the sanctions sought to demonstrate Western resolve and solidarity to prevent further Russian aggression.

However, Putin redefined the way that the sanctions work and deflected their impact away from the elites and on to the masses by imposing a set of counter-sanctions, which cut off food imports from the Western countries sanctioning Russia. For his part, Putin sought to reinforce his usual policy of divide and conquer with the West by encouraging Western businesses interested in benefitting from the Russian market to pressure Western governments to rescind the sanctions while allowing Russia to maintain its territorial gains.

The process of imposing sanctions and counter-sanctions seeks to take advantage of the growing interconnections in an increasingly globalized world. However, studies suggest that the use of such tools is not effective for either side. In fact, the threat of sanctions can often be more persuasive than actually imposing such limitations on trade.

Elite Gains

One of the examples of how the elite have gained from Russia’s countersanctions is the story of Agriculture Minister Aleksandr N. Tkachev. Tkachev became minister on April 22, 2015. From 2001–2015, he served as governor of Krasnodar Krai, one of Russia’s richest agricultural regions. During his tenure Russia held the winter Olympics in Sochi, a city in Krasnodar Krai, building up the infrastructure for a winter resort industry in a place where there had been none before. Putin paid considerable personal attention to ensuring that the sporting event was a success and undoubtedly was aware of Tkachev’s activities. Visitors to the area witnessed that some parts of the region developed impressively during Tkachev’s tenure, especially when Russia benefited from high energy prices on international markets.

Shortly after his appointment as minister, Tkachev came to prominent national attention when he was behind the destruction of food that had been imported into Russia in violation of the new sanctions against Western food producers. The destruction of the imported food was controversial at the time, but sent a strong message to society that the federal leadership was serious about implementing this measure even if it went against some elements of public opinion in Russia.

During his time as governor, Tkachev was well known for building up his own private agricultural holding company that made his family the sixth largest holder of agricultural land in Russia. Such outcomes do not raise eyebrows in Russia. In fact, a government commission recently found that there is no conflict of interest in Tkachev’s work as a public official and the rapid and simultaneous increase in property owned by his family. Tkachev’s holding company was originally founded by the governor’s father and is one of the largest in Krasnodar Krai. It grew to be 33 times larger while Tkachev was governor. Tkachev used his position to obtain tax breaks which benefit his company, according to Forbes. With his support, the company continues to buy up land and other companies.

While it is difficult to know why the Kremlin makes specific decisions, the case of Tkachev’s promotion as minister of agriculture seems to have resulted from concern that he was growing too powerful as governor of his region. In Krasnodar, former Governor Tkachev had an independent base of power. Following his transfer to the federal cabinet, his position is more directly vulnerable to Prime Minister Dmitry Medvedev, who is reliably loyal to Putin. Nevertheless, despite his exposed position, Tkachev has been able to use his post to continue enriching himself and his family, so the economic benefits continue to flow into his pocket. His agricultural companies benefit from Putin’s counter-sanctions blocking food imports, which makes it easier for Tkachev’s companies and other Russian producers to sell their products on the domestic market. In short, well placed Russian elites may be vulnerable to the whims of the president, but they continue to be enriched by his policies.

Masses Tightening Their Belt

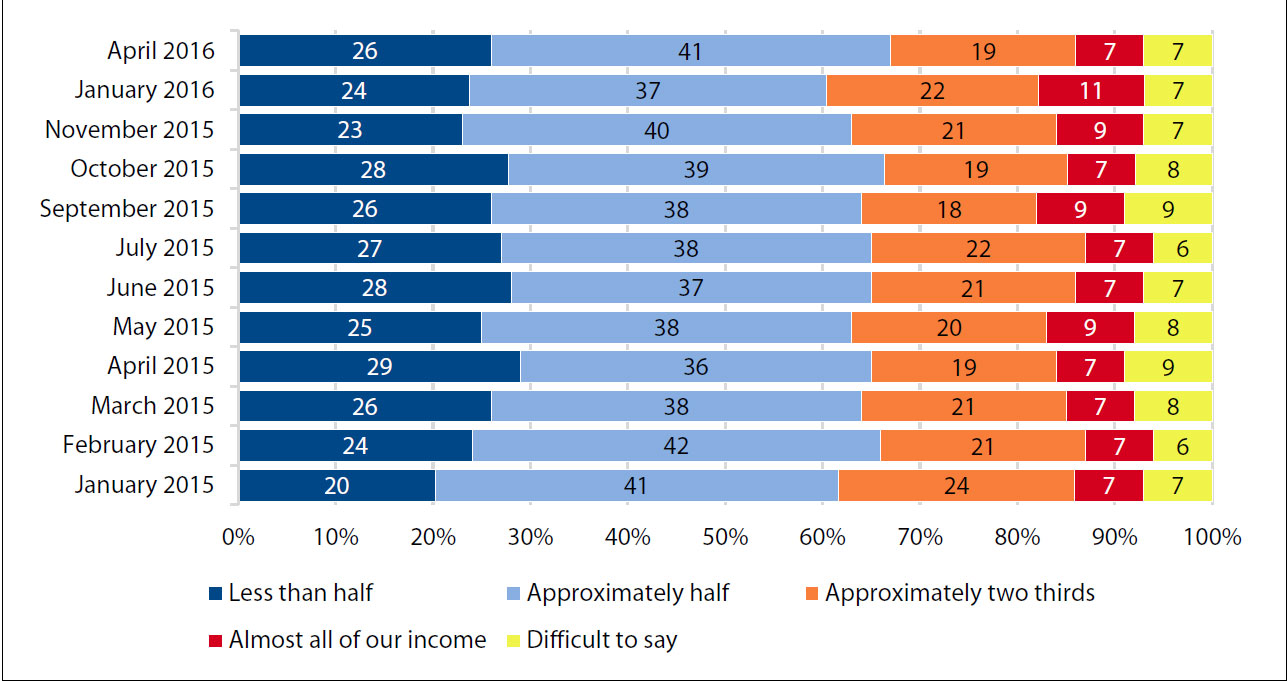

At the same time as the elites are profiting from the situation, the masses are feeling increasing pain. As the variety of food available has shrunk, prices have gone up for ordinary consumers. The rising costs of imports in Russia has affected key goods for the agricultural sector, including equipment, spare parts, fertilizer, breeding livestock and seeds. Farmers also have difficulty getting bank credits due to high interest rates. Food now consumes more than 50 percent of the monthly budget of Russian families, according to Institute of Social Analysis and Forecasting at the Presidential Academy of National Economy and Public Administration.1 Additionally, imports from non-Western exporters are now more expensive because of the current weakness of the Russian ruble, which has lost more than half its value in recent years.

The current problems have brought Russia back to the same level as the crisis of 2008–9. In 2015, the poverty rate grew to 19.2 million people or 13.4 percent of the population, the highest number in nine years, according to Rosstat. Not only is the situation bad, it is continuing to deteriorate as the share of food in family budgets continues to grow.

But, since the Russian media machine defines the West as the aggressor, many ordinary Russians see their country as a victim of external machinations rather than blaming their own leaders. Most people do not link their personal economic problems to Putin, the Russian elite, or the extensive corruption in the country. They are effectively demobilized from taking any action.

In Krasnodar Krai, big agricultural holding companies are continuing to buy up land throughout the region by using the corrupt powers of the state, including buying off local politicians and judges, and intimidation.2 Farmers were organizing a protest in March, threatening to drive their tractors to Moscow, but the authorities intervened to prevent that from happening. These farmers supported Putin’s policies to block food imports because it helped them. Additionally, the state has provided more aid to rural areas, though resources are increasingly tight. Among the farmers’ demands were the resignation of Tkachev, whose company has used harsh tactics to buy up land and benefits from more state aid than other businesses. In this sense, Russia is a place where the best corporate raiders are appointed to lead government ministries, according to local journalist Svetlana Bolotnikova of Kavpolit.

The consolidation of large agricultural holding companies is a process that has been going on for more than a decade. Following the collapse of the Soviet Union, there simply were not enough farmers in the former state and collective farms who could take over the land. While the sources of change within society are weak, and the chances for the appearance of a powerful protest movement seem small, the situation remains brittle and unpredictable.

Conclusion

Analysts frequently point out that Russian elites now stand alone in their society. The country’s democratic institutions have been eviscerated, civil society is passive, and corruption has hollowed out most state structures.

At the same time, there are sources of resiliency in Russian society. The story of Primorsky Konditer, a chocolate factory in Vladivostok, provides one example of this source of societal strength (see next article in this issue of the RAD). The result is that society has the resources to survive, but not to transform the overall political situation. Accordingly, Russia will continue to fail to live up to its full potential.

Notes

- <http://www.ranepa.ru/uceniyy-issledov/strategii-i-doklady-2/bulletin>

- <https://www.opendemocracy.net/od-russia/svetlana-bolotnikova/pitchforks-are-coming-russia-protests>

About the Author

Robert Orttung is Director of Research at the George Washington University Sustainability Collaborative and Associate Research Professor at the Elliott School of International Affairs.

Recommended Reading

- Emma Gilligan, “Smart Sanction against Russia: Human Rights, Magnitsky, and the Ukrainian Crisis, Demokratizatsiya: The Journal of Post-Soviet Democratization 24: 2 Spring 2016.

- Tatiana Nefedova, “Kto prokormit Rossiiskoe naselenie,” Kontrapunkt, No. 3, April 2016.

Figure 1: Approximately How Much of Your Family’s Income Do You Spend on Food?

Vladivostok’s Primorsky Konditer: A Regional Success Story

By Yevgenny Popravko, Vladivostok

Abstract

The Vladivostok chocolate maker Primorsky Konditer is an example of a resilient company that has survived the vagaries of the Russian economic transition. It is a case study in the adaptive capacity of small parts of the Russian economy in the face of larger negative influences.

Far Eastern Sweets

Chocolate bars laced with seaweed are among the latest products of the famous Vladivostok chocolate and confectionary factory Primorskiy Konditer (PK), a source of pride among local residents. As usual in Russia, the story behind the chocolate is one of intrigue, politics, and ultimately, overcoming adversity through grit and determination.

To begin with, Vladivostok natives are enormously proud of the local confection called Bird’s Milk (Ptichye Moloko). The basic recipe for these famous cakes and chocolates with their fluffy meringue filling came to the Soviet Union from Poland1. However, in 1967 local expert Anna Chulkova (recently named a Distinguished Citizen of Vladivostok2) developed an absolutely new technology that changed the story of these chocolates. She added agar-agar, a gelatin extracted from sea weed, to the creamy filling, radically improving the taste of the product and making it much healthier.

Since that time, Vladivostok denizens have been fond of passing on a box of “Ptichye Moloko” to their friends, relatives, and business partners. In the Soviet Union, the brand and the agar-agar recipe was freely used by different factories all over the country. However, “Birds Milk” produced in Vladivostok was considered the best. The Vladivostok factory also produced a number of other famous Soviet brands of chocolates and candies, including “Mishka na Severe (Baby Bear in the North)” and “Lastochka (Swallow).” There were no trademarks under Communism, so factories could appropriate intellectual property as they pleased. Thanks to PK, Vladivostok residents did not encounter a serious shortage of sweets and cookies even in the Soviet era, when shops were often empty and people had to stand in line to buy basic goods.

Fending off the Moscow Behemoths

After the collapse of the USSR, a swirling scandal began that still affects the Primorskiy Konditer factory. In the mid-1990s, a group of behemoth Moscow conglomerates registered all the famous Soviet brand names as their own property. In the 2000s, they begin to sue regional producers for using these very trademarks. The goal was to bankrupt the regional producers or to acquire them. The Moscow firms succeed with their hostile takeovers in many regions since the regional companies had to pay multi-billion ruble fines and lost even more money in rebranding their own products. For example, PK’s beloved Ptichye Moloko is now called Primore Classic (Primorskie Classicheskie), named after the ocean front region which made it famous.

At the moment PK is one of a handful of factories that survived the Moscow attack. The reasons:

- 1) they have very good lawyers

- 2) they are supported by the local authorities

- 3) they won the sympathy of a loyal and adoring local public, and

- 4) PK produces high quality products.

PK does not rest on its past success, but continues to innovate. In the last few years, Primorskiy Konditer has developed the “ShikoVlad” brand3, an absolutely new line of local chocolates that stresses their regional origin and ingredients. Chocolates with sea weed and sea salt are definitely jewels of this collection. PK did not have the money to launch an ad campaign, but customers immediately noticed these chocolates. PK decorates its chocolates with the paintings of local artists and photos of local sites. They also name their chocolates after local landmarks, like Russian Island, which sits just off the coast of Vladivostok. While it is hard to measure the true success of ShikoVlad, these chocolates are extremely popular and they are saving PK’s business.

ShikoVlad Chocolates With (From Left to Right) Sea Weed, Wafer Crumbs, and Sea Salt

Primorskiy Konditer Confectionary Store

A Long History

Primorskiy Konditer is one of the oldest local enterprises in Vladivostok. It was founded in 1906. According to the company’s official history, it began to experiment with producing agar-agar in 1932 along with scientists from TINRO, an Academy of Sciences subsidiary studying oceanology. The experiment was a success: in 1936 Moscow allocated funds for building facilities for agar-agar production so that the Vladivostok confectionary could put an end to the “country’s dependence on imported agar-agar.”

In the 1930s the company began experimenting with local forest plants. It organized teams to gather wild grapes, various berries (including limonnik), and apples, using up to 300 tons of “wild” ingredients a year for producing candies and marmalade. The use of forest ingredients was stopped because they turned out to be too expensive. However, one can definitely say that the company has been experimenting with local natural ingredients for a long time.

Over time PK has woven itself into Vladivostok’s local folklore. Primorskiy Konditer is located right next to the regional Federal Security Service (FSB) headquarters. So Vladivostok residents often use “konditerskaya fabrika” as a way of talking about the FSB without mentioning the organization by name. For example, “I received a call from konditerskaya fabrika,” “I was visited by two konditerskaya fabrika employees.” Local writer Vasiliy Avchenko explains this phenomenon by the universal folk tradition of not mentioning sacred names (like God, the devil, bears, or tigers), but replacing them with some other words. Locals also joke that the KGB headquarters were built next to Primorskiy Konditer to keep the local agar-agar and Bird’s Milk recipes “as secret as the recipe for Coca Cola.”

As for the sea weed in the chocolate, its Latin name is laminaria, known to many American beachgoers as kelp. Laminaria is widely used in Japanese, Korean and Asian cuisines. The seaweed trade was the first profitable business in Vladivostok after the city was founded in 1860. The first settlers sold laminaria to Asian countries. Just as the native Americans introduced the pilgrims to North American plants and animals, Asians introduced continental Russian migrants to a number of local products, such as laminaria, crabs, sea cucumbers, and scallops.

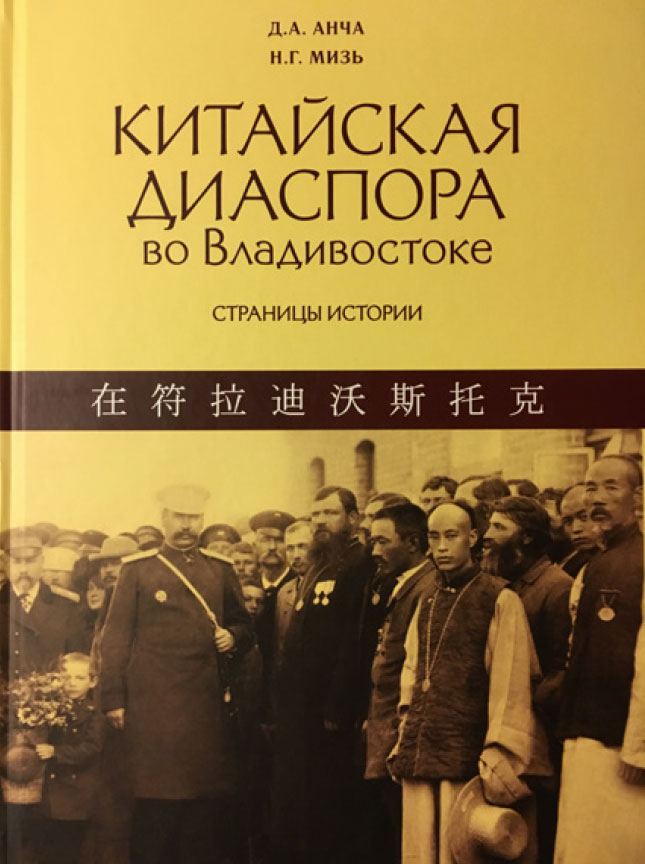

The Cover of “Kitaiskaya Diaspora Vo Vladivostoke” [The Chinese Diaspora in Vladivostok] by D.A. Ancha and N.G. Miz'

The chocolate bars with sea weed and sea salt reflect the local traditions of Vladivostok’s Asian location. But they also embody the globalizing trends that are sweeping Russia, even as Putin tries to isolate his population from foreign influences. The Asian-infused sweets are made on equipment recently imported from Switzerland.

Current Conditions

While Primorskiy Konditer is definitely a point of local pride, it often becomes a source of negative news. The latest incident happened in March 2016 when a Vladivostok district court shut down the company’s production due to violations in the way that it used ammonia processing equipment. Public comments in local social networks and mass media online forums confirmed the popular support for PK: people bashed the judge for the “unpatriotic” verdict and demanded that the authorities intervene. Ultimately, Far East Presidential Envoy Trutnev demanded an investigation into the situation and two weeks later a Primosrkiy Kray regional court annulled the district court decision.

However, some observers note that the latest case happened due to the fact that PK management is too “greedy” and did not take enough care of its equipment. They point out that in 2006 PK did not invest in any PR events or publications to celebrate its 100 anniversary, suggesting that current expenditures are not in the plant’s long-term interest.

Notes

- <http://www.sras.org/bird_milk_cake>

- http://vestiprim.ru/2015/05/29/razrabotchik-ptichego-moloka-anna-chulkova-nagrazhdena-pochetnoy-gramotoy-dumy-goroda-vladivostoka.html

- http://www.eastrussia.ru/material/ptichku_zhalko/

About the Author

Yevgenny Popravko is an observer of life in Vladivostok.