Russian Analytical Digest No 197: Media

10 Feb 2017

By Maria Lipman and Nozima Akhrarkhodjaeva for Center for Security Studies (CSS)

The two articles featured here were originally published by the Center for Security Studies in the Russian Analytical Digest on 23 January 2017.

Independent Media Live On in Putin’s Russia

Independent Media in Moscow and Beyond

In December 2016, Meduza.io, a Russian-language political and public affairs website operating from Riga (Latvia), published its own choice of that year’s best pieces of Russian journalism.1 The Meduza competition was quite informal and its criteria unclear, but it suggests that the Russian media scene is richer than it might seem given the Kremlin’s repressive actions during President Vladimir Putin’s third term.

The Meduza list included the Russian contribution to the Panama Papers investigation, a large-scale cross-border journalistic effort that exposed dubious business and financial operations by government officials and other prominent figures. Three Russian journalists who participated in the Panama Papers project published in Novaya Gazeta serious allegations against members of the Russian elites, including Putin’s long-time personal friends.2

Another Meduza choice was Aleksey Navalny and his Anti-Corruption Foundation (FBK), whose report exposed Deputy Prime Minister Igor Shuvalov using an undeclared $62 million jet. Navalny is an anti-graft crusader who has for years conducted investigations of Russia’s highest-ranking elites. The awarded report revealed that the plane had been often used by Shuvalov’s wife Olga to deliver her Corgi dogs to dog shows in Russia and abroad.3

Yet another item on the list was a lengthy reportage from a mining town in the Far North where a mine explosion killed 36 people.4 The miners interviewed in the piece described egregiously neglected safety standards. The article was published on 7x7, a website operating from Syktyvkar in Komi republic in the Russian north. The site’s full name is 7x7—Horizontal Russia; it describes itself as a “space free from the state”, “an independent project”. “We set an ambitious goal for ourselves”, the founders of 7x7 explained as they introduced their website to the readers, “to attract for cooperation all forces that are alive in Russian civil society. Our goal is to cover provincial regions of the Russian North-West, Center, Volga and Urals regions and to create horizontal communities of active bloggers”.

As the example of 7x7 shows, “free from the state” outlets are not limited to the Moscow liberal milieu. Nor are they exclusively leftovers of the freer environment of the earlier times: this is true of Novaya gazeta, which has operated since the early 1990s, but 7x75 was formally registered as a mass media outlet in March 2014, two years into Putin’s third term marked by a crackdown on rights and freedoms.

It is indeed easy to make a case for the government’s tightened grip on the media,6 which is—just like any non-state actor—fully at the Kremlin’s discretion. But the government still shows a degree of tolerance and does not use its discretion to turn every media outlet into a Kremlin mouthpiece.

And, as long as this is not the case, there are journalists willing to continue their professional pursuit, so the minority of readers, viewers or listeners who are interested in nongovernment sources of information do not have a problem finding them.

Political Irrelevance

Until 2012 Putin’s Kremlin mostly left alone smalleraudience, niche media, as long as they did not wield any political authority. Keeping such outlets politically irrelevant was not a difficult task in an environment stripped of political competition, one in which formally existing checks and balances were thoroughly emasculated. This way the nongovernment media (a shorthand for those outlets whose operation is guided by something other than the desire to support the Kremlin line) were able to produce political news, but could not perform the function of public accountability. Another way to describe it is that the Kremlin didn’t mind if those media preached to the converted, but made sure they remained within their niches and did not stir undesired sentiments among a broader public.

The limits of tolerance were expanded a bit during the presidency of Dmitry Medvedev who famously proclaimed that freedom was better than non-freedom. Moscow liberal journalists grew emboldened—even some outlets that had been focused on entertainment grew politicized. When anti-Putin rallies broke out in late 2011, journalists were at the forefront of the protest activism.

After Putin’s return to the Kremlin the following spring, those niche liberal media that previously had been left alone came under pressure. The pressure, however, did not amount to repressions of reporters or editors.

A Vast Toolkit for Limiting Speech

The Kremlin has at its disposal a vast toolkit that it can use to force some of the more audacious outlets to tone down their critical line—short of directly harassing or persecuting individual journalists. Those tools may include stripping media of advertising—those who buy advertising space or time would readily shun the outlets that have displeased the Kremlin. Or cable providers may suddenly choose to drop their client, apparently acting on instructions from “above,” as was the case with TV Rain.7 The audience of this independent television channel dropped from about 12 million viewers when they were included in cable packages to about 70,000 Internet subscribers in 2016.8

Instead of going after individual journalists, the Kremlin relies on media owners to do the job. Over the years of Putin’s rule, media assets have been redistributed, so now all major media that the Kremlin can use as its political resource are either owned directly by the state or concentrated in the hands of just a few of Putin’s loyalists. And even many of the smaller-audience, niche media are the property of those who can be trusted to scale back excessive audacity. So when lenta.ru grew too defiant—and too popular, the owner fired the top editor; subsequently, almost the whole team resigned in protest.9 Lenta.ru remains in business, but it has grown tame. Its former editor and part of her team have since launched the above-mentioned Meduza.io in Riga.

It did not take persecution or law-enforcement measures to tame Kommersant once Russia’s best mainstream daily newspaper owned by one of Russia’s wealthiest tycoons Alisher Usmanov. Neither did it take harsh measures to depoliticize Moscow’s hip glossies that in the late 2000s developed an interest in politics. At the urging of their owners, they were reformatted to refocus on leisure and entertainment.

And if a wealthy media owner does not take care of taming his publications, the Kremlin can remind him who is boss. This was what happened to Mikhail Prokhorov, the owner of RBC, a media group whose operation grew too defiant. The new team of talented and energetic top editors that took charge of RBC in early 2014 began to produce first-rate political and public- affairs coverage. Some of its investigative reporting touched upon Putin’s innermost circle, including his daughters. In spring 2016 RBC’s daring performance led to searches in Prokhorov’s business offices sending a signal that some of his associates might be prosecuted or jailed. Prokhorov promptly responded: top editors of RBC were either fired or submitted their resignations as a sign of protest. The Kremlin spokesman flatly denied that it played any role in the crackdown on RBC and called any such suggestions “absurd”.10

Getting fired by the owner does not amount to being “black listed”. When a prominent journalist or editor loses his or her job, he or she has a reasonably good chance of finding a new one—if this is what one chooses to do (some prefer to look for a different career or spend some time abroad). All outlets realize that they are vulnerable, but this does not mean that all grow tame. TV Rain may struggle economically after it was dropped by cable operators, but it still pursues editorial independence. RBC’s new top editor said point blank that he would not run stories about Putin’s daughters, but it would be unfair to say that RBC’s editorial standards have been radically compromised.

The Benefits of Allowing Some Freedom

But why does the Kremlin tolerate even a modicum of free expression?

In the past a common argument was that the Kremlin did it for show—in order to demonstrate to the Western world that the Russian government was concerned about rights and freedoms. However, those times are gone—Putin’s Russia firmly rejected the position of a disciple and made it clear that it is unconcerned about the West’s judgment. These days Russia is anxious to demonstrate to the West its military might and hard-hitting foreign policy—not abidance by liberal norms.

A major reason for its relative tolerance is that the Kremlin regime, while undoubtedly authoritarian, is still not tough. It seeks to keep societal forces under control, yet not by intimidating its people into silent submission, but by ensuring broad public acquiescence.

This acquiescence was undermined in 2011–12 at the time of the mass anti-Putin protests, but following the annexation of Crimea in Spring 2014 the Russian people rallied around their leader. This effect proved to be amazingly long-lasting: for almost three years now Putin’s approval rating has never dropped below 80 percent. The regime reinstated its legitimacy in the eyes of the vast majority; the interest in protest rallies has faded, and a majority of Russians believe that Russia is on the right track11 despite declining personal incomes.12

The regime’s legitimacy, which in the 2000s was based on rising incomes, in the 2010s has been buttressed by nationalism—a sense of pride in Russian military might and Russia’s resurgence as a global power, as well as the declared rejection of Western models. This nationalist sentiment has been given a tremendous boost by the bellicose rhetoric of officialdom and state-controlled television, but the yearning for national self-esteem had been growing for many years before the hostilities in Ukraine. Putin’s assertive foreign policy, his forceful statement that “we are stronger than anyone, because we’re right” delivered to the people what they had overwhelmingly wanted to believe.13

In this environment of almost universal loyalty to the leader, the government can permit small, critically-minded constituencies to find ways of self-expression in their niche spaces—such as media outlets or social networks. The opportunity of self-expression serves the function of letting off steam, thereby ensuring even broader acquiescence.

Alternatives Deemed Unappealing

Alternative information is thus available, but the vast majority, motivated by the high approval rating of the leader who made Russia strong and proud, does not find such information appealing or convincing. This is why when the Malaysian jet was downed over Ukrainian territory in the summer of 2014, a mere 3 percent of Russians believed that it was shot down by the pro-Russian insurgents14 (although the information that pointed to the pro-Russian insurgents was easy to find), while over 80 percent laid the blame on the Ukrainian military. Similarly, Aleksey Navalny’s allegations or those made by the Panama Papers project left people unimpressed.

It would be wrong to suggest, however, that official statements or news on state TV enjoy universal credibility— polls show that people don’t want to appear gullible and have limited trust in what TV reports (56 percent Russians surveyed by Levada center in November 2016 said they have “full” or “significant” trust in national television broadcasts.15 But even if they fail to trust the official sources fully, the sense of loyalty motivates the vast majority of Russians to stick to them—and turn away from the available alternative sources of information, which they may see as disquieting, vaguely subversive, playing into the hands of the Western enemy or threatening to undermine Russia’s strength. This enables the government to remain relatively lenient in regard to nongovernment media—while, of course, keeping them keenly aware of their vulnerability.

Graeme Robertson described this phenomenon in a piece that explains why reports of election fraud published by independent observers left Russians unimpressed:

“If citizens do engage heavily in motivated reasoning, then popular authoritarians may have less to fear from freedom of information (…) than many have argued, especially if the opposition is unpopular. While social media are certainly important for exchanging information, building solidarities and organizing within like-minded communities, increasing the availability of critical viewpoints does not necessarily mean that these views will become widespread.”16

Besides letting off steam, the nongovernment media outlets may serve another function, that of a platform for internal strife among the political elites. Novaya Gazeta is one example. In 2015 the assassination of Boris Nemtsov was followed by a standoff between the Federal Security Service (FSB) and the leader of Chechnya Ramzan Kadyrov, whose close associates were suspected of being involved in the assassination. The FSB shared with Novaya Gazeta reporters its complaints over Kadyrov’s defiant conduct and obstruction of the investigation. Arguably the target audience of these publications was not the readership of Novaya Gazeta, but the president himself, to whom the FSB pledged (unsuccessfully) to rein in the Chechen leader. During Putin’s third term the squabbling and rivalry among the elites have shown no sign of subsiding. Not that the leaks generated by such struggles would make the elites accountable or ease the regime’s grip, but at least this might mean that nongovernment media will remain in demand.

Notes

1 https://meduza.io/feature/2016/12/28/rizhskiy-balzam-2016

2 http://krug.novayagazeta.ru/12-zoloto-partituri

3 https://navalny.com/p/4952/

4 http://semnasem.ru/vorkuta-shakhty/

5 http://7x7-journal.ru/about/portal

6 https://www.theguardian.com/world/2016/may/25/how-russia-independent-media-was-dismantled-piece-by-piece

7 http://www.newyorker.com/news/daily-comment/asking-the-wrong-question-on-russian-tv

8 http://www.svoboda.org/a/27561599.html

9 http://www.newyorker.com/news/daily-comment/putin-moves-against-the-press

10 https://www.ft.com/content/45a8a9c4-1c3b-11e6-b286-cddde55ca122

11 http://www.levada.ru/2017/01/25/yanvarskie-rejtingi-2/

12 http://www.rbc.ru/economics/18/11/2016/582f01659a7947168d07a873j

13 http://kremlin.ru/events/president/news/47054

14 http://www.levada.ru/2014/07/30/katastrofa-boinga-pod-donetskom/

15 http://www.levada.ru/2016/11/18/doverie-smi-i-tsenzura/

16 https://www.cambridge.org/core/services/aop-cambridge-core/content/view/S0007123415000356

About the Author

Maria Lipman is the editor of the on-line journal external pageKontrapunktcall_made and is currently a visiting lecturer at Indiana University, Bloomington.

Russian Media and Journalists’ Dilemma between “Exit, Voice, and Loyalty”

Abstract

The Russian media landscape has undergone significant transformations in recent years. While television has been subordinated predominantly to the Kremlin, print press has been losing its critical voice. Nevertheless, during interviews with media professionals conducted by this author few openly admit the existence of government or editorial censorship. Did journalists suddenly become loyal to the Kremlin, or are they afraid to admit that they are no longer able to report on controversial issues? Drawing on Albert Hirschman’s approach of “Exit, voice, and loyalty”, this article demonstrates how the Russian government ensures that media outlets take a pro-Kremlin position without resorting to excessive violence, open censorship, and other overtly coercive measures, but instead relies on “softer” and more sophisticated tools deploying its administrative resources.

Raising the Cost of Dissent

Over the past decade, the content of Russian federal television channels and even the print press has become increasingly pro-Kremlin. Various views have been advanced to explain why journalists produce pro-government reporting. Growing pressure on journalists and censorship were some of the most plausible explanations. However, despite the worsening media environment and the decline in the number of critical voices, few media professionals actually admit that their freedom is restricted by the editors, management or state authorities, although they acknowledge that they think about the potential consequences of their reporting. Moreover, Schimpfossl and Yablokov (2014) argue that Russian anchors and reporters who advance Kremlin’s positions on federal television do so voluntarily.

In autumn 2015, I conducted 11 interviews with print media journalists working in Moscow for some of the widely read newspapers serving intellectuals and businesspeople. Interestingly, none of the journalists admitted official censorship at the newspaper level, although some said they think about the possible consequences of their reports. Some even said that there are cases in which they would report on a controversial subject despite being aware of possible consequences and claimed that the risk of reprisal does not stop them. Others argued that it is possible to report on controversial but worthwhile topics. When asked directly about censorship from above, the respondents from the Kommersant and Vedomosti newspapers claimed that as long as clear facts are provided, the editors would accept their articles for publication. Yet, critical reporting is rare in the print media and nearly absent on federal television channels. If it is not censorship, as media professionals claim, then what stands behind this pro-Kremlin news reporting? What could explain journalists’ loyalty? Is it a fear or unwillingness to admit censorship? Or do journalists truly support the Kremlin’s views?

Albert Hirschman’s theory on responses to decline in firms, organizations, and states argues that any organization— be it a business firm, a political party, a government, or even a state—can face a deterioration in performance. When such event transpires, actors and groups have a choice between either expressing their discontent (Voice); opting out (Exit), or accepting the status quo (Loyalty). The choice is also conditioned by appraisal of the costs. If the costs of the voice or exit options are too high, individuals opt for loyalty. In the case of deteriorating government performance, the costs of voice and exit can be regulated by the authorities.

Based on the data I gathered during my interviews in Moscow, I argue that in the Russian case the government raised the costs of voice, expressions of discontent or criticism of government policies, for the media to such an extent that those journalists who hold critical views are either being forced to quit and replaced by more loyal reporters, or prefer to stay silent. This effect is achieved predominantly in two subtle ways: 1) management’s hiring and firing practices, and 2) uncertainty regarding the rules of the game. In other words, unlike more traditional forms of media restrictions—such as excessive violence, open censorship, and overtly coercive practices—“softer” and more sophisticated tools deployed by the regime for keeping media loyal in Russia.

Hiring and Firing Practices

One way to ensure compliance without resorting to open censorship is by screening the political views of the potential employees before offering them a position, and firing current employees whose views deviate from the editorial line of the media outlet. During my interviews, some of the respondents argued that during the hiring process, the editor makes sure that the new employee fits well with the existing team and that his views neither deviate from those of the team, nor contradict the outlet’s editorial policies. As one journalist working for Russia Today (online-web edition) said,

“Why would an employer hire someone who would go against the employer’s views? Most often people gather around themselves those who are like-minded. We do have some variations in opinions in our media outlet, but in general, we share core ideas. We invite people who are more like us.”

Another interviewee, a journalist and an editor of an independent newspaper, gave an example from his own experience. He reported that a few years ago, while applying for a job at state-owned media, he was informed by the editor-in-chief (behind closed doors) that conditions had changed. While previously they could propose their own topics, now the topics and theses are provided by the authorities. However, if one does not agree with the new conditions, one cannot join the team.

Likewise, Schimpfossl and Yablokov (2014: 310) argue that many of their respondents “hold the view that, if a media personality and reporter does not agree with the editorial policy of one media organization, he or she is free to change to another organization.” Similar to reporters working for regional TV channels who have been interviewed by Koltsova (2006) those interviewed by Schimpfossl and Yablokov also “seem to freely promote their masters’ view.”

Firing: Journalists from the main federal channels who gave interviews to Colta.ru (2015) also noted that anyone whose views contradicted those promoted by the management were free to go. Those who left did not make a big fuss: they just left. Others stayed for various reasons. In the end, however, this policy ensured a team that was both homogeneous and compliant with spoken and unspoken rules. Another case in point is NTV. This independent TV station provided critical reporting during the first Chechen war as well as balanced coverage of the 1995 parliamentary elections. The channel was considered as having “a strong news and analytical component” (Belin 2002: 19). However, in 2001, the company was acquired by Gazprom-Media, and the management of NTV was replaced, while dozens of its regular employees resigned (Belin 2002).

Similar practices have been used in dealing with smaller media outlets or television programs. Stanislav Feofanov, a producer who used to work on REN TV’s “Nedelya” noted:

“In comparison to other programs on REN TV, Nedelya was trying to provide objective reporting, and present the views of both sides. I do not remember cases of censorship on ‘Nedelya.’ Perhaps, some questions were disputed between the editor in chief and the management of the channel, but, I, personally have not faced anything of the sort. But it was clear that the program was on the edge of collapse. Its dismissal was not a surprise. When the ‘Boeing’ was shot down [MH17 in Ukraine], it was impossible to cover the event the way we used to cover it… We were on vacation when we received a message from our editor: ‘Dear all! The moment has come when our proud little program is to be closed. Ahead of us is a beautiful world, where life will be completely different.’ Now, some of us work as freelancers, others do not work at all, some stayed on REN TV.”

An interview with a former employee of the All Russia State Television and Radio Broadcasting Company (VGTRK) also reveals that media professionals are forced to choose between exit and loyalty:

“In February 2014, there was a meeting, during which the editor-in-chief said that a ‘cold war’ is about to start…therefore, those who do not want to take part in it should find themselves some other job, outside the information channel, while the rest are welcome to the club. Very few left, and even they did not do it right away, they left in time, quietly, without making much noise… The rest stayed.”

Such hiring/firing practices ensure that only loyal employees stay, while those who speak up, disagree with the editorial line or attempt to raise their voices are either asked to leave or not hired at all. Such micromanagement practices have become increasingly common countries like Russia, and more research is needed to uncover the workings of these techniques.

Uncertainty

Uncertainty about the rules of the game and the consequences of breaking them ensures that those who do not opt out of the system remain loyal. A reporter working at Kommersant admitted being careful in choosing his words and topics in reporting; however, he argues that it is not due to censorship or pressure from the top, but rather, is consistent with a saying: “no need to anger the bear.” As one of the interviews published on Colta. ru (2015) states: “the rules leave room for interpretation”. And this uncertainty about the rules of the game, and the consequences of one’s actions might encourage those media professionals who would rather express their opinions to opt for loyalty and be careful despite the absence of open censorship.

The principle of uncertainty and how it works can be observed both in interviews that I have conducted and in interviews in secondary sources. It seems that stability and compliance can be ensured through deliberately creating an ambiguity about the rules of the game, so that nobody really knows how to act, what is allowed, and what is not allowed. This way, even if there is no direct pressure, a journalist “double checks” before taking any action, and based on the decreasing number of critical voices on Russian media, it can be assumed that most of the time, reporters prefer to be cautious. As the reaction to any report comes only after its publication, it is difficult to predict whether one will “get away with it,” receive a warning from the state telecommunications regulator, RosKomNadzor, or worse, get fired or be subjected to threats.

Even existing formal regulations are blurry. For example, an interviewee from Novaya Gazeta, an independent opposition newspaper, mentioned that there is a regulation that forbids the use of swear words in publications, however, there is no official list of prohibited words. Thus, a journalist must consider whether the commission will consider any particular word to be in violation. The extensive anti-terrorism law that Putin signed in force on July 7, 2016 gave the authorities another bundle of instruments that can be used to control the media. The implications of the law are very broad and, according to the same interviewee, it can be stretched even further. For instance, a publication about the state authorities being corrupt might be considered as an article attempting to spark hatred against state officials, or a publication containing any symbols of extremism, even when it is necessary for the topic, would lead to a penalty. Another law on securing personal data is also subject to various interpretations and restricts reporters’ actions significantly. For instance, when reporting on poor conditions and child abuse in orphanages a journalist must ask for the permission of the orphanage’s directors before proceeding. As such permission is unlikely to be given, the article would not be able to state either the name or the address of the orphanage or the names of the children who have been subjected to abuse.

Another example of uncertainty was given by a Kommersant reporter, who said that he does not feel any pressure when writing or publishing his materials and that there are no prior rules about, or prohibitions on, any topics. However, there is a shared understanding, common-sense knowledge among journalists that some topics are better left untouched. Unless a reporter openly violates unspoken rules, there is no way to determine whether unpleasant consequences will follow. Thus, to be on the safe side, some might take precautions in choosing topics, whereas others might decide to speak openly about controversial issues. Again, based on the principle of uncertainty, the critical voice is either punished or not. Perhaps that is one of the reasons that some islands of a relatively free press in Russia still remain. Additional examples of such uncertainty can be seen in an interview conducted by Schimpfossl and Yablokov (2014: 309), where an interviewee working on television told a story about inviting a writer who had just lost Putin’s favor for an interview:

“[w]e asked ourselves: maybe we should not have him [the writer] here anymore? And without any instruction from above our team decided to cancel the interview. Our producer gave him [the writer] some lame excuse that some technical equipment broke down here in the studio or something. The program is pre-recorded, so we could have actually just cut out some bits if necessary, but we wanted to cover our backs… He [the writer] instantly wrote about it on Twitter, and in the end we had a scandal.”

An interview with a former VGTRK employee published on Colta.ru (2015) may serve as another example of uncertainty:

“For example, there was a parade in Serbia. Not really in honor of Putin, in honor of the victory, but Putin was there… The parade was really amazing, beautiful. ‘Rossiya-24’ was feeding a signal from Serbian TV and broadcasting the parade in Moscow. The Serbs organized everything, we organized a translator who translated the words of the parade presenter. There was only a small complaint that the interpreter was a girl. The editor-in-chief was absent: his deputy was replacing him. Prior to leaving, the editor- in-chief told his deputy, ‘We will show only a part of the parade, and the rest can be transmitted through a small window.’ Apparently, this issue had not been agreed upon with the officials. What happened next was that after broadcasting part of the parade, as told by the editor-in-chief, the deputy chief moved the parade into a small window. At that moment, the phone starts ringing, Dobrodeev calls three or four times, screaming to put the parade back on and broadcast it till the end. Yelling at the same time about a woman translator—why could not you find a male translator? … Of course, we returned the parade to the air, however, even after that there were phone calls: ‘How could you, what are you doing?’ In principle, it was supposed to be editor-in-chief’s decision, but this is how it turned out in the end…”

As Schimpfossl and Yablokov (2014: 309) also note, “[t]he need for a reporter to sense what is appropriate at a particular moment in time might lead to insecurity and overly cautious approaches.” It is not about knowing, it is more about sensing, which creates the uncertainty that forces a person to think twice before taking any step: there is no need to resort to direct censorship or coercive practices.

When asked to compare levels of media freedom in the early 2000s and the 2010s, the majority of interviewees note that the media environment has worsened. However, when asked about changes at their own workplace, such as daily routines, editorial censorship, self-censorship, agenda-setting routines, or choices about how to frame news events, most of the respondents claim that they have the freedom both to choose their topics and to frame those topics as they see fit. Simultaneously, the majority of respondents note that although material has been approved for a publication, if a report is found inappropriate by external actors (i.e., state officials, business groups, or the ruling elite), the media outlet might receive a warning or, as one of the interviewees said, “it is not that the media is under direct pressure, but if a critical article appears in a newspaper, the next day, the building of that media outlet might be shut down under the pretext that the building is in a state of disrepair or undergoing reconstruction, and other things of that sort.” This signifies that the ruling elite exerts control over the media and its content by creating uncertainty about the possible consequences of controversial reports by using, or rather abusing, state administrative resources.

Conclusions

In summary, based on this data, instead of excessively coercive strategies the Kremlin uses more subtle micro-management tools to control the media. Uncertainty raised by the ambiguity of rules and regulations subtly forces the media professionals either into self-censorship, which is not often openly acknowledged, or causes a loss of their position. This shows that on the one hand, there is no direct censorship, whereas on the other, there is some uncertainty about potential responses to controversial publications. By abusing state administrative resources, the ruling elite creates an ambiguity in the interpretation of the rules, thus ensuring “carefulness” or voluntary self-censorship by media professionals. The management and editors of a media organization employ the same “carefulness”, which in turn, shapes their hiring and firing practices, paving the way for new media professionals who are loyal to the Kremlin.

This combination of two strategies, i.e., increasing the costs of voice, and making exit easy, ensures that in a majority of cases a media professional chooses either to take a pro-Kremlin position, or at least not to express openly his discontent; or to opt for exit with the possible prospects of not being able to return to the profession until conditions change.

About the Author

Dr. Nozima Akhrarkhodjaeva is a researcher at the Research Centre for East European Studies at the University of Bremen (Germany). She is currently working on a research project entitled “Media control as a political power resource. The Role of Oligarchs in the Post-Soviet Region” with support from the Centre for East European and International Studies (Berlin). Her PhD thesis, which will be published by ibidem Press / Columbia University Press in April 2017, analyzes the media coverage of presidential election campaigns in Russia.

Recommended literature:

• Belin, Laura. 2002. “The Rise and Fall of Russia’s NTV,” Stanford Journal of International Law 38 (19): 19–42.

• Koltsova, Olessia. 2006. News Media and Power in Russia. Routledge, Taylor and Francis Group.

• Hirschman, Albert. 1970. Exit, Voice, and Loyalty: Responses to Decline in Firms, Organizations, and States. Harvard University Press.

• Schimpfossl, Elisabeth and Yablokov, Ilya. 2014. “Coercion or Conformism? Censorship and Self-Censorship among Russian Media Personalities and Reporters in the 2010s,” Demokratizatsiya 295–311.

• Sidorov, Dmitriy. 2015. “Kak Delayut TV-propagandu: Chetire Svidetel’stva,” colta.ru. Retrieved from http://www.colta.ru/articles/society/816

Consumption and Perception of Mass Media by the Russian Population

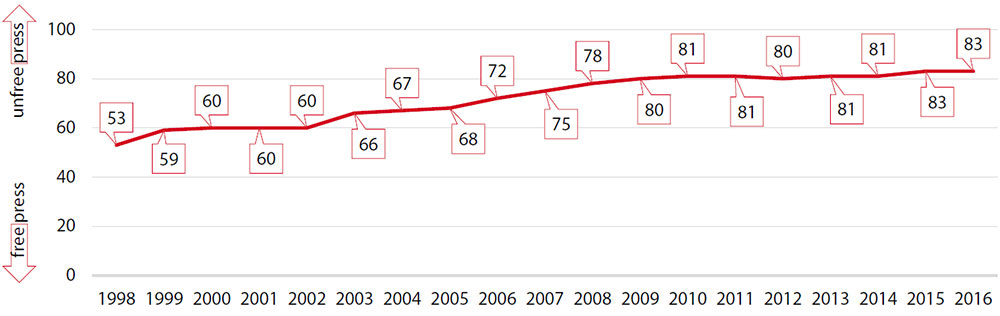

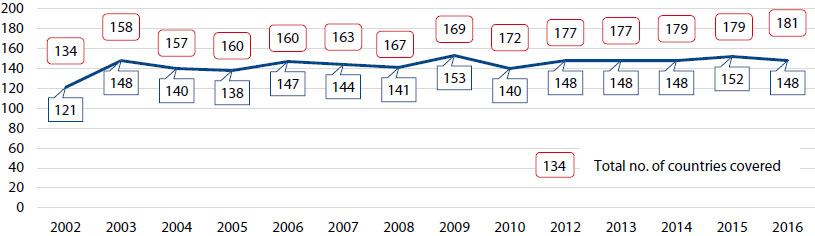

In the past few years, freedom of the press has been deteriorating in Russia. Reports and indices compiled by Freedom House (Figure 1) and Reporters Without Borders (Figure 2) clearly indicate this trend.

The content of national television channels has been becoming increasingly pro-Kremlin. Critical media outlets are either marginalized, like Novaya Gazeta, have limited access to broadcast, like Dozhd', or the management of the outlet is completely replaced by a more compliant editorial board, as was the case with NTV and more recently with Lenta.ru and RBC.

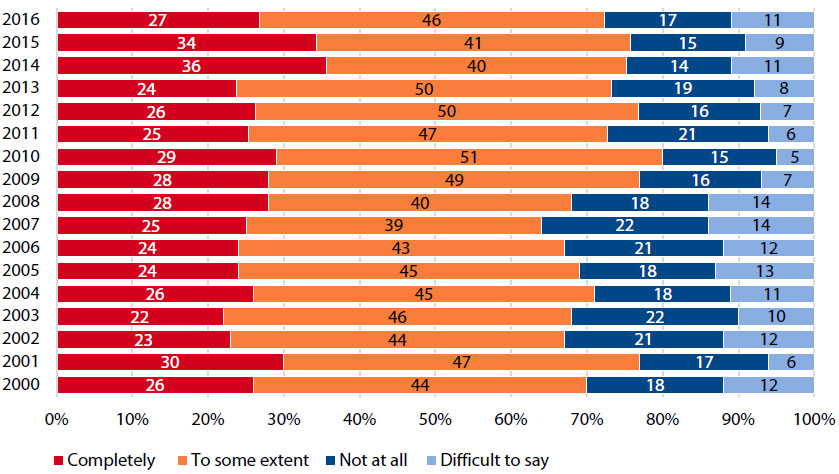

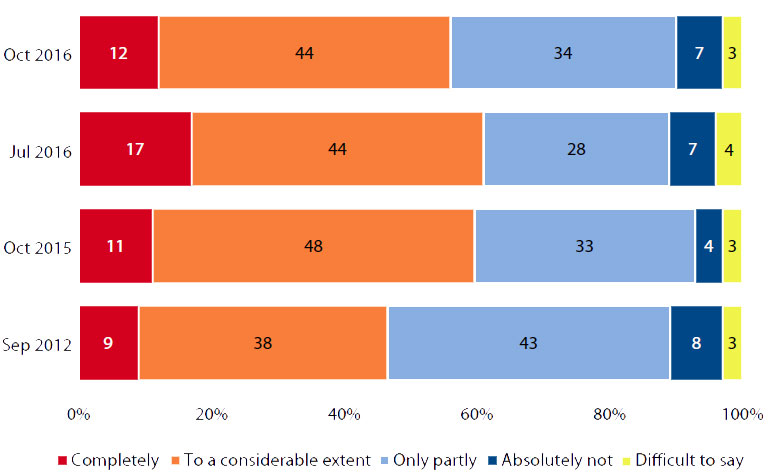

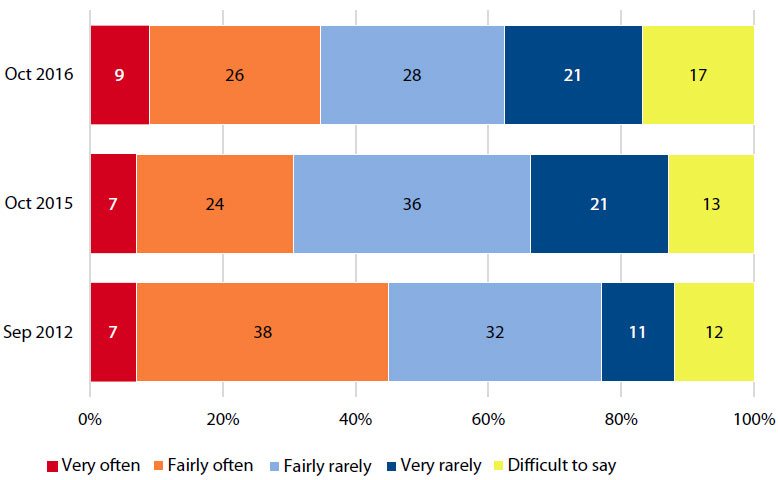

How does the audience react to this trend? How much does the Russian population trust the media? A survey conducted in 2000 by the independent Russian public opinion institute Levada Center shows that despite the fact that at that time the media enjoyed relatively higher levels of freedom compared to recent years, 18% of respondents in 2000 stated that they did not trust the media at all (Figure 3), while in 2016 only 7% said they did not have confidence in what they saw on television (Figure 4). In 2016, 90% of the respondents claimed that they trusted television at least partly. Interestingly when the question was reformulated, 35% admitted that while watching television, listening to the radio, or reading the newspaper, they felt deceived or that they were given false information; 49% said it rarely happened (Figure 5).

However, despite all this, on average, Russians do trust the media, and especially their main source of information— television. According to Levada Center’s survey (Goriashko 2016), 59% of the population trust television, although 78% reckon that some officials hide the truth or even lie when talking about the state of affairs in the country. 20% trust internet publications, and 12% trust the information received from friends and relatives. Mostly respondents claim that television provides the most objective information when it comes to international affairs (58%), domestic affairs (27%), and the life of ordinary Russians (25%). According to these data, the majority of Russians trust television and its objectivity, however they tend to distrust senior officials appearing on TV, assuming that they might be deceiving or hiding the truth from the people.

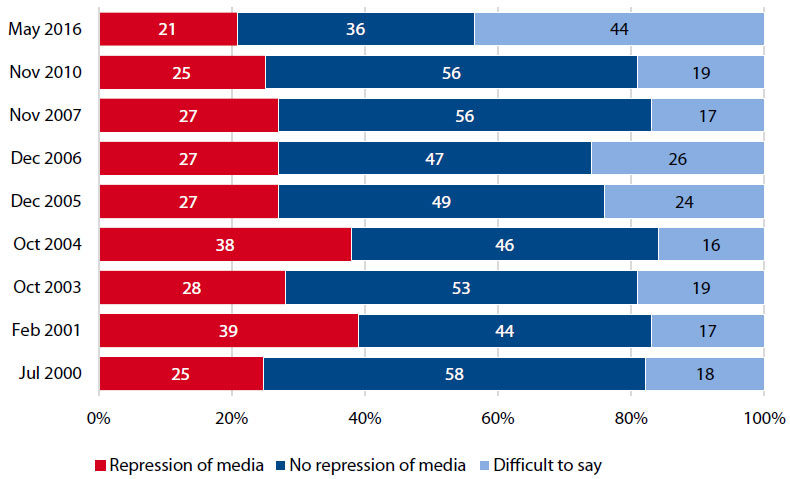

Despite the worsening media environment, the percentage of the population who believes that the authorities are repressing freedom of speech and/or undermining the independence of the media changed only slightly, from 25% in 2000 to 21% in 2016 (Figure 6). But the numbers of those who think that the authorities do not threaten freedom of expression and are not infringing on the activities of independent media did change considerably. In 2000, 58% thought that the media was not under any kind of threat; by 2016 only 36% of the population claimed that media freedom is not endangered. Interestingly, the numbers of those who found it difficult to assess the situation doubled since 2000.

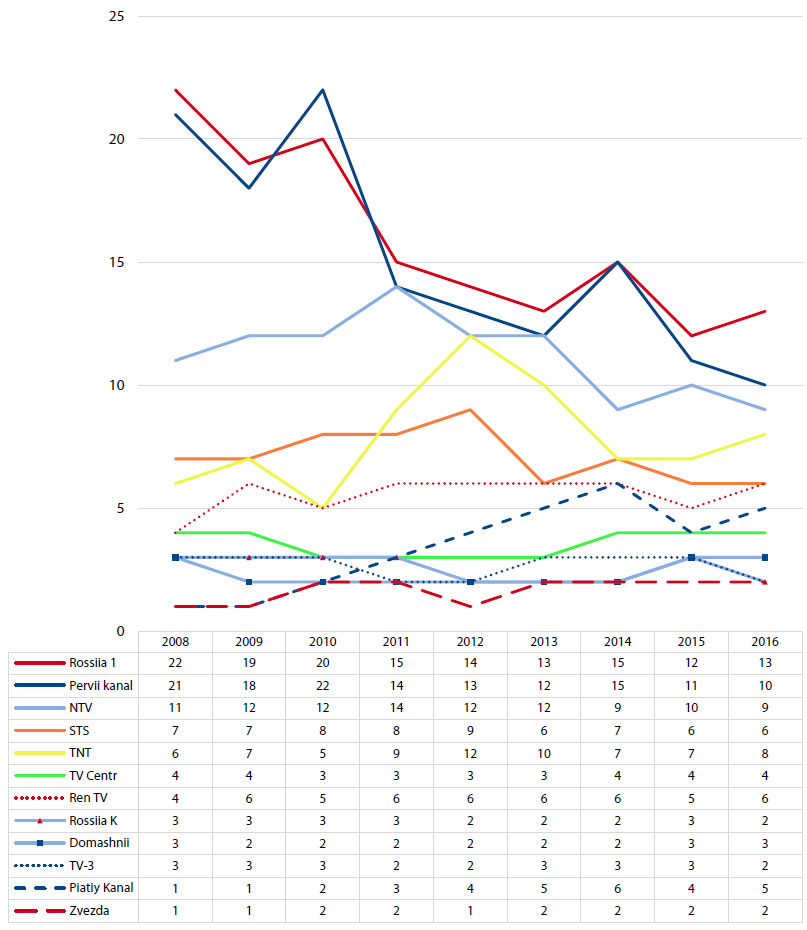

The limited awareness of and concern for the worsening media environment displayed by the Russian population can be explained by the following factors: 1) the majority of the population receives information about current events in the country via television. Surveys conducted between 2009 and 2014 show more than 90% of the population prefer television to any other information source (Levada 2014); 2) the television channels with the highest rankings are Rossiia, Pervii Kanal, and NTV. All three channels are partially or fully owned either by the state or via state companies such as Gazprom Media; 3) On these television channels, critical assessments of current events as well as recent cases of pressure exerted on some media outlets, such as Dozhd' or RBC, are not reported.

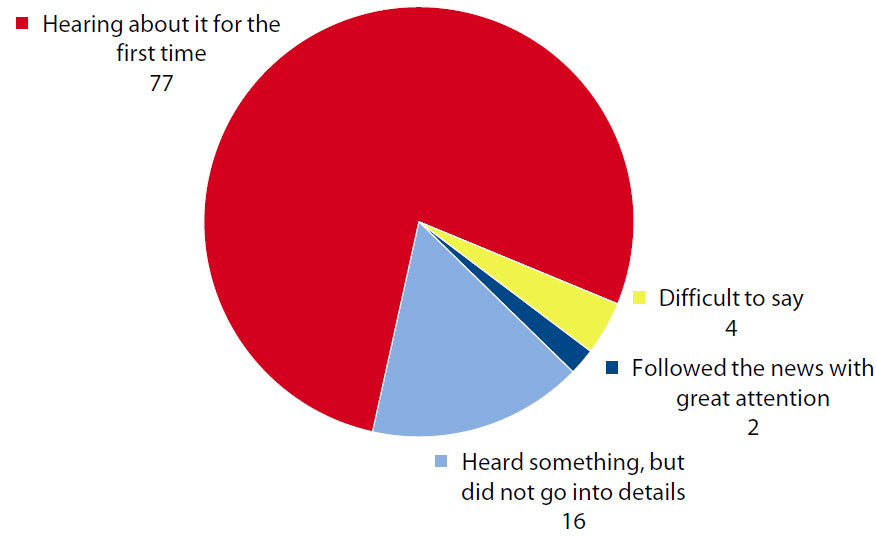

To illustrate this point: in early April 2016, RBC, a media holding company owned by one of Russia’s oligarchs and gaining increasing popularity in the country, published a series of articles related to the “Panama papers.” In one of them, RBC presented evidence collected by the International Consortium of Investigative Journalism (ICIJ) demonstrating that 1.3 trillion USD had been moved from Russia and 2 billion USD were siphoned off by Putin’s circle alone. A month later, in early May, the management of RBC was changed and 20 journalists had left. This news was published by Vedomosti, Novaia Gazeta, and Meduza, but not broadcast on national TV. Opinion polls conducted a week after the editorial board of RBC had been replaced showed that 77% of respondents had not heard about it (Figure 7).

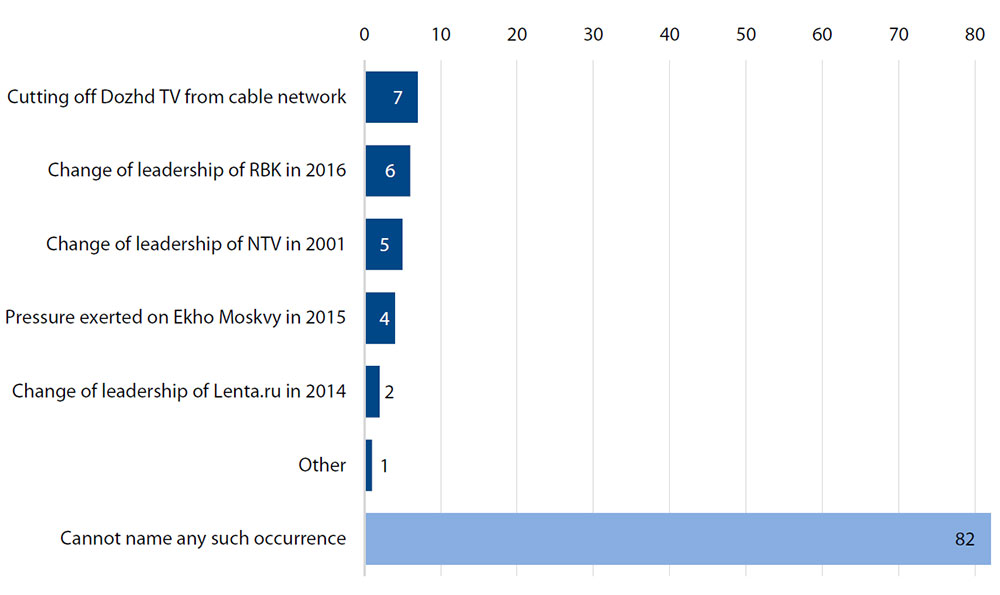

Likewise, Lenta.ru—one of the most popular online media outlets—went through similar changes in leadership in 2014. The whole editorial board was fired, including Editor-in-Chief Galina Timchenko, dozens of correspondents, all photo editors and administrators. Later, Timchenko started her own online media platform Meduza, registered outside Russia. Although these events took place relatively recently, only 2% of respondents could recall the change of leadership at Lenta.ru and 6% said they had heard about RBK. 82% of all respondents could not name any case when freedom of the press had been violated (Figure 8).

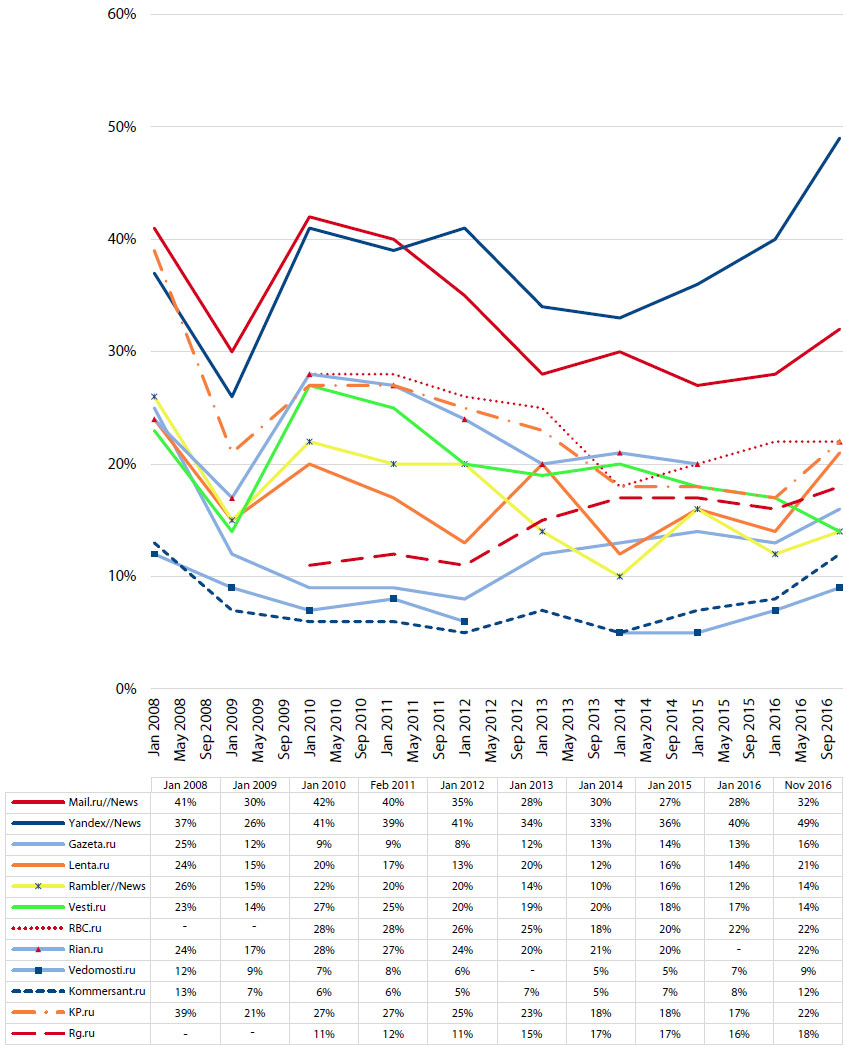

To sum up, the Russian media landscape has gone through significant transformations during the last decade, however, according to opinion polls, people continue to trust television and it still is the principle source of information for the majority of Russians. This reliance on television in turn makes it easier for the state to distribute information sympathetic to the incumbent government. Perhaps, state control might drop with time, as more and more Russians are turning to the Internet. As of 2016 the level of internet penetration reached 70.5% in the country (Internet-World- Stats 2016). Simultaneously, the level of trust in internet publications has been increasing in recent years, from 29% in 2012 to 36% in 2015. But the state’s attempt to control the internet has also risen. Since 2014 blocking of online content expanded and the government passed several laws restricting online activities.

Nozima Akhrarkhodjaeva

References:

• Goriashko, Sergei. 2016. The citizens hardly trust the officials. Kommersant. http://www.kommersant.ru/doc/3060925

• Levada. 2014. Russian media land scape: television, press, internet. Available at http://www.levada.ru/2014/06/17/rossijskij-media-landshaft-televidenie-pressa-internet/print/

• Internet World Stats. 2016. Top 20 countries with the highest number of internet users. Available at: http://www.internetworldstats.com/top20.htm

International Rankings of Press Freedom

Figure 1: Russia’s Score in the Freedom of the Press Index (Freedom House): Scores Range from 0 (Best) to 100 (Worst)

Source: Freedom House. Available at <https://freedomhouse.org/report/freedom-press/2016/russia>

Figure 2: Russia’s Rank in Reporters Without Borders’ Press Freedom Index (Compared to Total Number of Countries Covered)

Source: Reporters Without Borders. Available at <https://rsf.org/en/russia>

The Russian Population’s Trust in the Media

Figure 3: To What Extent Can Today’s Press, Radio, and Television Be Trusted?

Source: Representative opinion polls of the Russian population conducted by Levada Center, 2000 – 23–26 September 2016, <http://www.

levada.ru/sites/default/files/levada_2010_rus.pdf>, <http://www.levada.ru/2016/10/13/institutsionalnoe-doverie-2/print/>, <http://

www.levada.ru/2015/10/07/institutsionalnoe-doverie/print/>, <http://www.levada.ru/2014/11/13/doverie-institutam-vlasti-3/

print/>, <http://www.levada.ru/sites/default/files/om13.pdf>

Figure 4: Do You Trust the Information About Current Events in the Country Distributed via the Main Television Channels?

Source: Representative opinion polls of the Russian population conducted by Levada Center, September 2012 – 21–24 October 2016,

<http://www.levada.ru/2016/11/18/doverie-smi-i-tsenzura/>

Figure 5: While Watching Television, Listening to the Radio, or Reading the Newspaper, Do You Ever Get the Feeling That You Are Being Deceived or Given False Information?

Source: Representative opinion polls of the Russian population conducted by Levada Center, September 2012 – 21–24 October 2016, <http://www.levada.ru/2016/11/18/doverie-smi-i-tsenzura/>

The Russian Population on Media Censorship

Figure 6: Some Think That Russian Authorities Are Repressing Freedom of the Press and Undermining the Independence of the Media; Others Think That the Authorities Do Not Threaten Freedom of Expression and Are Not Restricting the Activities of Independent Media. Which Of These Views Is Closest To Yours?

Source: Representative opinion polls of the Russian population conducted by Levada Center, July 2000 – May 2016, <http://www.levada.

ru/2016/06/06/smi-vnimanie-i-tsenzura/>

Figure 7: Did You Hear That a Week Ago the Management Of RBK Media Holding Was Fired? (May 2016)

Source: Representative opinion polls of the Russian population conducted by Levada Center, May 2016, <http://www.levada.ru/2016/06/06/

smi-vnimanie-i-tsenzura/>

Figure 8: Can You Name Any Cases of State Pressure on the Mass Media? (Multiple Answers Possible, May 2016)

Source: Representative opinion polls of the Russian population conducted by Levada Center, May 2016, <http://www.levada.ru/2016/06/06/smi-vnimanie-i-tsenzura/>

Media Consumption in Russia: Most Popular Media Outlets

Figure 9: Most Popular Television Channels in the First Weeks of Each Year (Viewers as % of Total Population)

Source: TNS: Mediascope. Television audience, <http://mediascope.net/services/media/media-audience/press/information/ratings/>

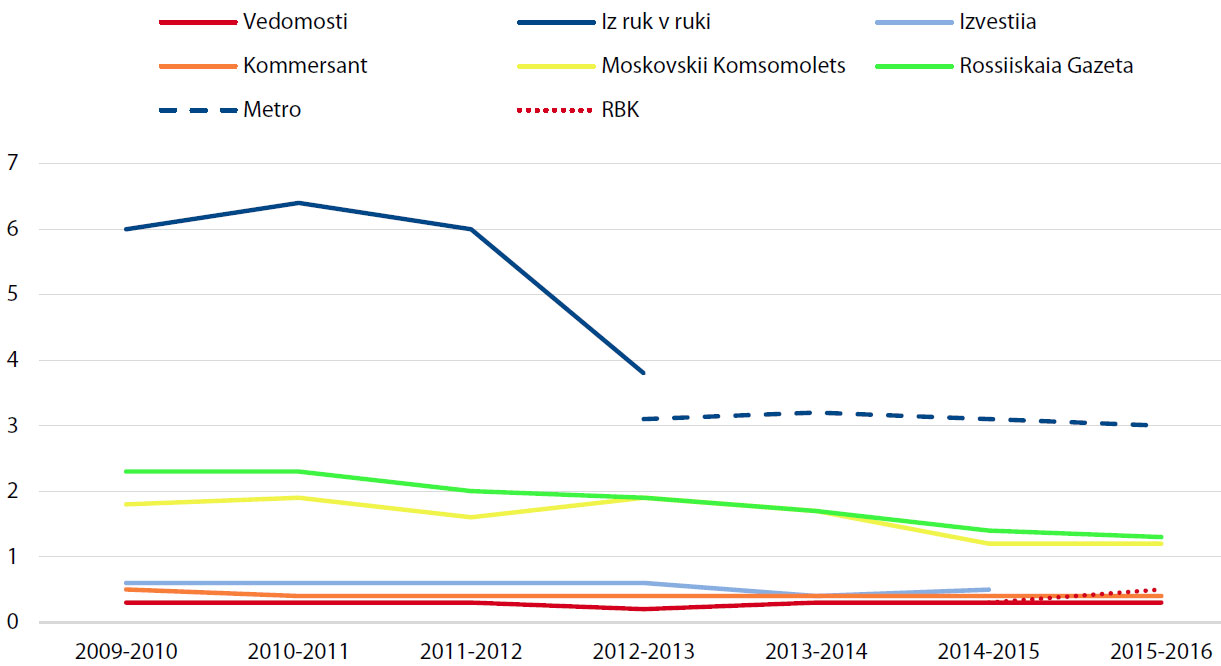

Figure 10: Most Popular Newspapers in Russia, September 2015 – February 2016 (Single Issue Audience: % of the Population)

Source: TNS: Mediascope. Press readership, <http://mediascope.net/services/media/media-audience/press/information/ratings/>

Table 1: Most Popular Newspapers in Russia, September 2015 – February 2016 (Single Issue Audience: in Thousands and in % of the Population)

Source: TNS: Mediascope. Press readership, <http://mediascope.net/services/media/media-audience/press/information/ratings/>

Figure 11: Most Popular Online News Media (Users As % of Total Number of Internet Users)

Source: TNS: Mediascope. Web Index Report, <http://mediascope.net/services/media/media-audience/press/information/ratings/>

For more information on issues and events that shape our world, please visit the CSS Blog Network or browse our Digital Library.