Russian Analytical Digest No 217: Russian Presidential Elections

4 Apr 2018

By Margarita Zavadskaya and Eugene Huskey for Center for Security Studies (CSS)

The two articles featured here were originally published by the Center for Security Studies (CSS) in the Russian Analytical Digest on 26 March 2018.

The Fight for Turnout: Growing Personalism in the Russian Presidential Elections of 2018

By Margarita Zavadskaya

Abstract

The role of presidential elections in sustaining authoritarianism differs from legislative elections because they are closely intertwined with the personalism associated with presidential power. The Russian political regime is moving toward a consolidated personalist authoritarianism where presidential elections signal the leader’s strength and divide the opposition by increasing voter turnout.

Why Hold Elections?

In “Fiddler on the Roof,” the well-known musical based on the works of Sholem Aleichem, Tevye the milkman suddenly questions his wife Golda after several years of marriage: “Do you love me?” Taken aback, she retorts: “Do I love you? For twenty-five years I’ve washed your clothes, Cooked your meals, cleaned your house, Given you children, milked the cow, After twenty-five years, why talk about love right now?” The Russian presidential elections, held on March 18, the anniversary of what the Kremlin celebrates as Crimea’s “reunion” with Russia, took place almost 20 years into Vladimir Putin’s tenure. To continue the metaphor, these elections rhetorically question whether Russian voters still support the president after the “rally round the flag effect” generated by Russia’s successful military operations faded away.

Vladimir Putin competed against seasoned veterans—Vladimir Zhirinovsky from the LDPR and Sergei Baburin representing the puppet party Russian All-People’s Union, Grigorii Yavlinski from Yabloko, and new faces—Ksenia Sobchak, the daughter of former Putin boss Anatoly Sobchak who described herself as “the against all” candidate, Pavel Grudinin, replacing Communist Gennady Zyuganov, and outright spoilers Boris Titov from the Party of Growth and another communist Maxim Suraykin.

The question was rhetorical since no one doubted that electoral results were a foregone conclusion. But there is another question: Why hold elections and what is their purpose for those in power?

Do Elections Support or Subvert Autocracy?

The political science literature suggests that elections under autocracies are a double-edged sword that seek to sustain authoritarian rule, but under certain conditions may turn against the master. Some claim that repetitive elections gradually socialize politicians and voters and at some point democratize the regime. On the other hand, there is a good deal of evidence that clearly contradicts this proposition. Repetitive Russian elections—both legislative and presidential—do not seem to liberalize the regime.

Elections support autocracies in a variety of ways: decreasing the uncertainty that is endemic in all non-democratic regimes, coopting the elites, and dividing the opposition. In this sense the State Duma elections perform a number of useful functions of power sharing, spoils distribution, and splitting the opposition. In 2003 the newly formed United Russia absorbed a large number of independents and deputies from other political parties. In 2007 the political arena imploded four systemic parties and cut out the stronger opposition. In 2011 the authorities lost control of the Duma elections, when United Russia only managed to win 49.32% of the votes. The perception that the regime had cheated to gain even this result caused the massive For Fair Elections movement and protests. To calm the situation, the authorities had to make concessions to allow the registration of a large number of new parties. Finally, in September 2016, United Russia won a majority, but the elections were marred by low turnout rates and poor media coverage. The legislative elections of 2003 aimed at power-sharing and extensive cooptation, while the elections of 2007, 2011 and 2016 sought to send a credible signal about the regime’s strength. Only in 2011 did the administration fail to send such a signal.

Signaling Strength

The role of presidential elections in sustaining authoritarianism differs from the role that legislative elections play and is closely intertwined with the degree of personalism and presidential power. Under party-based authoritarian regimes, presidential elections largely serve the purpose of rotating the leadership among party members and information gathering, as in Mexico under the Partido Revolucionario Institucional (PRI) or Tanzania under the Chama-Cha Mapendusi (CCM). The degree of personalism is limited under such regimes. In contrast, the Russian political regime is moving toward a consolidated personalist authoritarianism where presidential elections are a demonstration of strength signaling the regime’s invincibility.

On March 18 Putin ran for his last term as the president under the revised constitution and sought to signal his political strength with renewed vigor. Elite cooptation does not play a big role when it comes to executive elections since there is only one person running for office. Nevertheless, the ability to send a strong and convincing signal to the elites, voters, and international community is of ultimate importance for Putin’s political survival and his further plans to retain power.

Elite groups should acknowledge once again that the incumbent is far from becoming “a lame duck”, he still enjoys popular support and continues to serve as the main intermediary in intra-elite negotiations and conflicts. Voters learned that there is no other viable alternative and the overwhelming majority of citizens apparently support the incumbent, even if some do not. The opposition supporters received a message that they are now deep in enemy territory and their resistance is futile. Lastly, the relevant decision makers from abroad obtained another piece of evidence that Putin, regardless of his ambiguous foreign policies, enjoys massive support as his main political asset.

The Turnout Controversy

The results of the elections in March did not make for a worthwhile intrigue. The leading state-sponsored Russian pollsters—FOM and VTsIOM—reported expected vote shares above 70%. The final tally was 76.69%. The independent pollster Levada Center was not allowed to publish its ratings since the state had declared it “a foreign agent.” However, the main battlefield unfolded around the expected turnout that demonstrated the legitimacy of the political credentials given to the president. Thus, the indicator to be maximized and delivered by the regional governors at these elections was the turnout statistics together with the election outcomes.

According to preliminary estimates by FOM and VTsIOM, the expected turnout was supposed to be exceptionally high—about 80%. In fact, the final turnout was 67.5%, slightly lower than anticipated. The Central Election Commission and the regional and local administrations put all their effort into mobilizing as many voters as possible. In January and February, thousands of voters received personal emails with reminders that they can cast a ballot even if they do not live where they are registered. Many were visited by municipal workers and precinct commission members at home. The Central Election Commission spent 700 mln rubles informing the citizens about the opportunity to vote. Vedomosti reported that Russian spin-doctors and election practitioners were asked to provide proposals on how to increase voter turnout.1 Ultimately, the elections sought to mobilize voters by entertaining them and varying the choice of new candidates, especially those with ambiguous political reputations, such as the show-woman Ksenia Sobchak.

The Boycott Controversy

The electoral competition is obviously unfair when the opposition is prevented from running. Aleksei Navalny and his supporters unleashed a countrywide campaign to boycott the elections after the authorities failed to register Navalny as a candidate. If turnout was the Kremlin’s main goal, the boycott campaign hit at the very heart of the idea to mobilize as many voters as possible. Ultimately, the boycott did not seem to be effective.

It came as no surprise that the leaders of Yabloko— one of the systemic opposition parties that was permitted to run—opposed the boycott, claiming it would not achieve the goals it sought. Along the lines of their logic, absent voters are no better than those who would not go anyway. As Boris Vishnevsky put it: “If opposition voters had not gone on strike in previous years, perhaps we would have had a different parliament and, maybe, a different president.”2 Ksenia Sobchak’s Civic Initiative and Pavel Grudinin’s CPRF advocate for the same approach: opposition voters should go to the polls to support their cause and to fulfill their civic duty. These statements clearly show how presidential elections keep dividing the opposition by allowing some of them to run and preventing others from doing so.

Boycotts decrease the odds of protests after elections since the voters already know that the quality of the elections fell short of international standards. Boycotting elections under personalist rule and under certain conditions could compromise the regime’s signaling function and potentially increase reputation costs in the eyes of the voters and international community. Given the fact that Aleksei Navalny had no other alternatives, this strategy seemed rational.

Sliding Back to Personalism

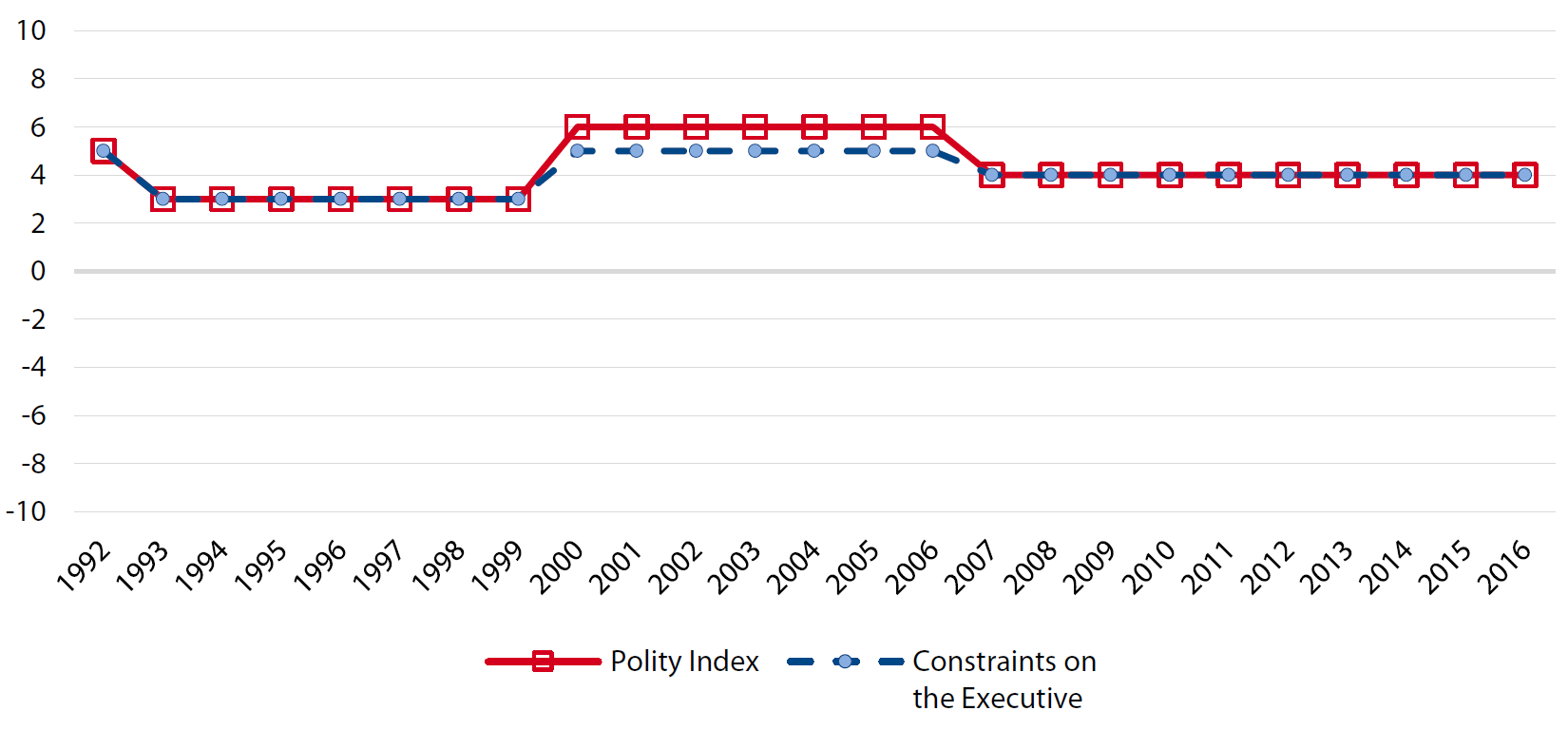

Strong presidential power or personalism reduces any cumulative democratizing potential elections may have. On the other hand, one should note that the degree of personalism has not always been the same throughout the last two decades; the Russian political regime has evolved since 1992 from failed attempts to build up a working “party of power” to marginally constrained personalism. The role of elections and turnout has changed accordingly. For instance, the measure of “Constraint on the Chief Executive” according to Polity has changed from 5, which stands for substantial limitations on the executive, in 1992 to 3, slight to moderate limitations, in 1993 to 1999. After 2000 the Polity measure of power constraint went back to “substantial limitations.” After 2007, the limits weakened again. Figure 1 below shows the oscillations of the Polity IV index of democracy that varies from -10 to 10 where 10 stands for full democracies. Constraint on the executive is a specific component of the Polity IV index that measures the extent to which the executive is institutionally constrained by the judiciary, the legislature, and other political actors. In other words, the Russian political regime lost its institutional capacity again following 2007.

Figure 1: Political Regime and Constraints on the Executive in Russia

The spread of personalism and the regime’s de-institutionalization continued even further. Polity measures only the institutional dimensions reflected in the law. But if we take a look at the changes in the nomination procedures for presidential elections, we will see that Dmitri Medvedev was nominated by United Russia and supported by a number of other political parties in 2008; Vladimir Putin was nominated by United Russia in September 2011. However, in 2017–18 he ran as an independent. These minor changes reflect the ongoing de-institutionalization and weakening of the rest of the party structures. Further personalization of power will unavoidably increase the signaling role of turnout, splitting the opposition voters and parties, and enhancing the muscle-flexing role of the Russian presidential elections.

Given the signaling and divisive nature of these elections, we observed dramatic inequality in the access to the electoral arena reflected in selective law enforcement. We clearly witnessed the full range of tools of voters’ mobilization: from mass entertainment and even food served at the polls to the blatant use of administrative resources and workplace mobilization. Observers witnessed ballot stuffing and Sergey Shpilkin identified irregularities in the vote totals which presumably filled in the gaps where voters did not behave as the Kremlin expected.

References

Smyth, R., & Soboleva, I. V. (2016). Navalny’s Gamesters: Protest, Opposition Innovation, and Authoritarian Stability in Russia. Russian Politics, 1(4), 347–371.

Morse, Y. L. (2018). Presidential power and democratization by elections in Africa. Democratization, 1–19.

Smith, I. O. (2014). Election boycotts and hybrid regime survival. Comparative Political Studies, 47(5), 743–765.

Zavadskaya, M., Grömping, M., & Martinez i Coma, F. (2017). Electoral Sources of Authoritarian Resilience in Russia: Varieties of Electoral Malpractice, 2007–2016. Demokratizatsiya: The Journal of Post-Soviet Democratization, 25(4), 455–480.

Notes

1 Елена Мухаметшина. Возможная явка на выборы не выросла ни на процент. Ведомости. <https://www.vedomosti.ru/politics/articles/2018/02/15/751020-yavka-vibori>

2 Борис Вишневский. Привести «своих», оттолкнуть «чужих». Низкая явка как терновый куст президентских выборов. Новая газета. 22.02.2018, <https://www.novayagazeta.ru/ articles/2018/02/22/75592-privesti-svoih-ottolknut-chuzhih>

About the Author

Margarita Zavadskaya obtained her doctoral degree in Social and Political Science from the European University Institute (Italy). She currently works as a postdoctoral researcher at the Aleksanteri Institute, University of Helsinki, senior researcher at the Laboratory for Comparative Social Research (Higher School of Economics) and researcher at the European University at St. Petersburg.

Putin Wins! Engineering an Election without Surprises

By Eugene Huskey

Abstract

By controlling the political narrative and the administration of elections, Vladimir Putin was able to achieve his most lopsided victory yet in the March 18, 2018 presidential election in Russia. Facilitating the favorable outcome for Putin was a cast of opponents whose backgrounds and behavior contrasted unfavorably with the sober, dignified, and professional image projected by the incumbent Russian president.

Another Six Years

Following an adroitly-managed presidential election campaign, Russia’s leader for the last 18 years, Vladimir Putin, won a new six-year term of office in decisive fashion on Sunday, garnering over 76 percent of the vote. If President Putin completes his new term, he would be only the second ruler of post-Imperial Russia to have governed the country for more than 20 years; the other was Joseph Stalin.

Perhaps the only elements of drama in the campaign surrounded the final margin of victory and the level of turnout. For leaders in soft authoritarian regimes like Russia, it is not enough to defeat opposing candidates. One must project an aura of political invincibility, which requires reducing opponents to also-rans in high-turnout elections where there are at least the formal trappings of competitiveness.

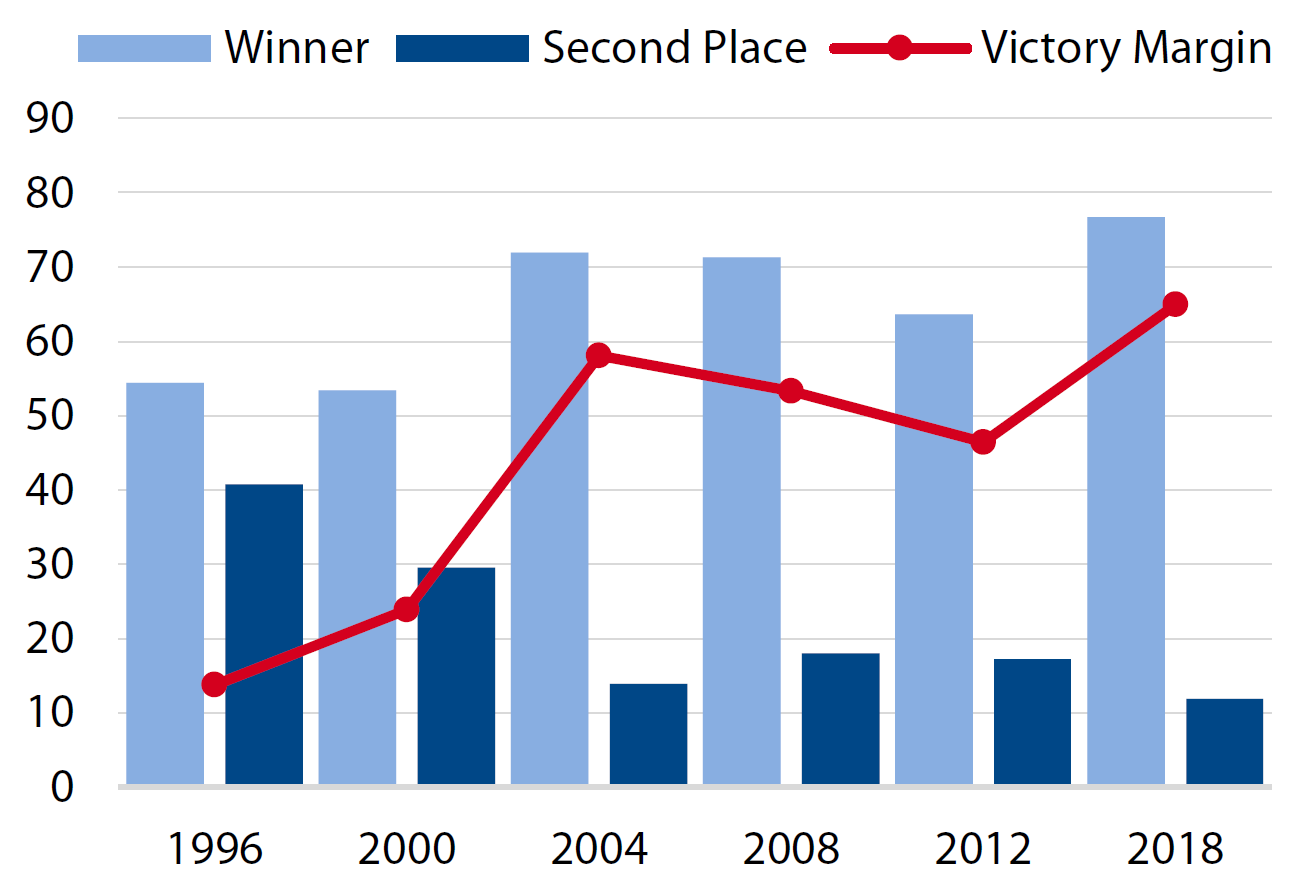

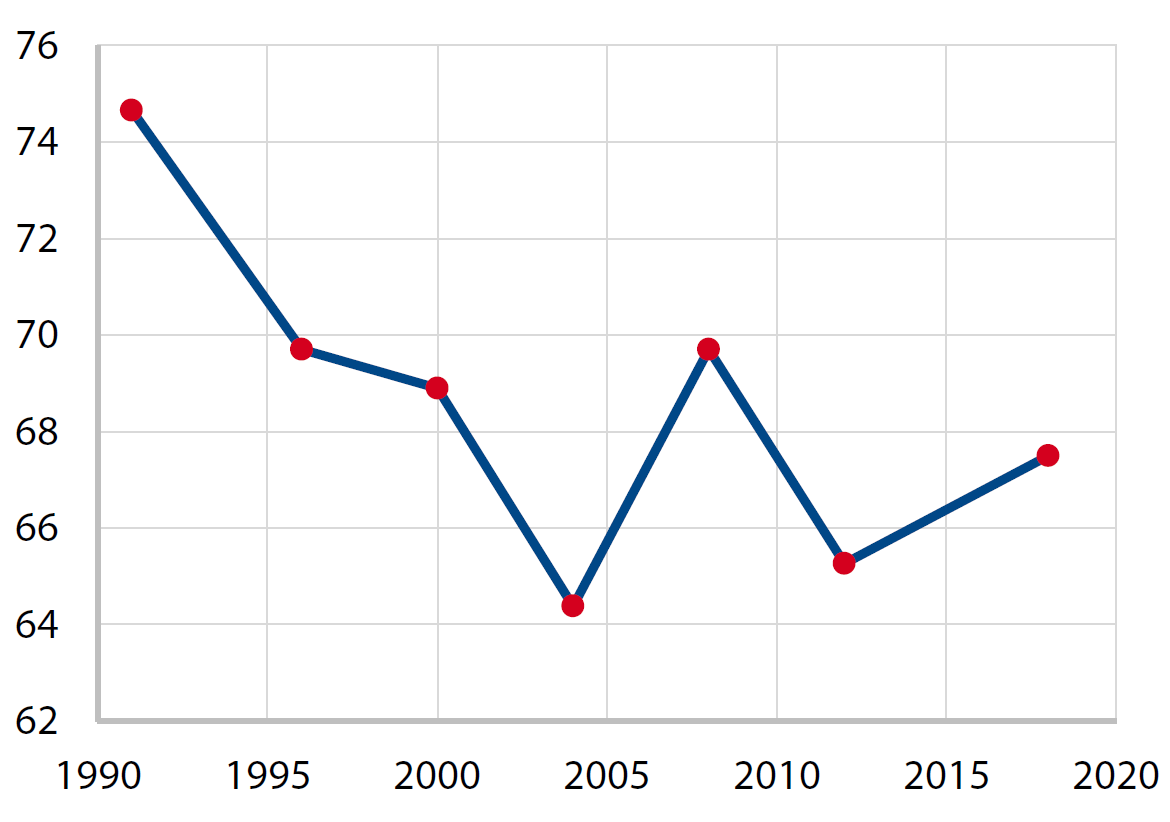

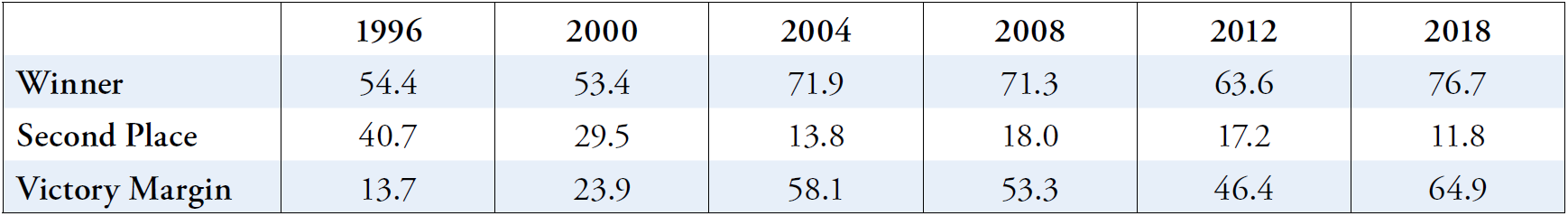

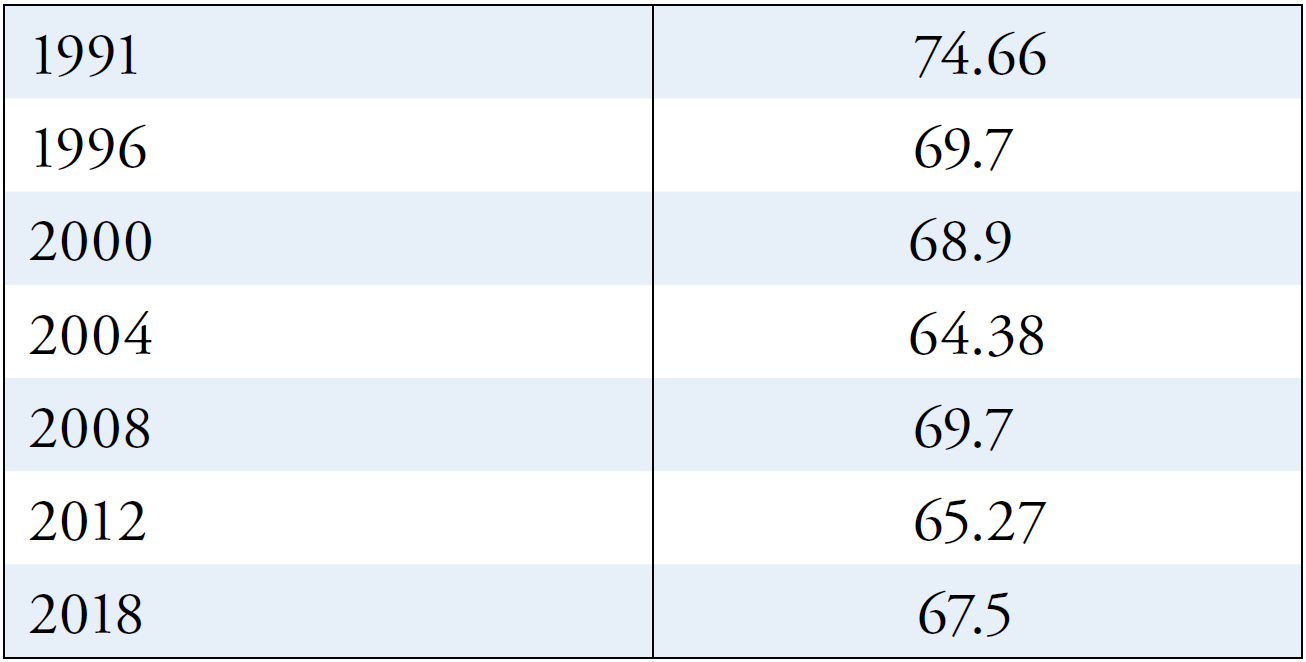

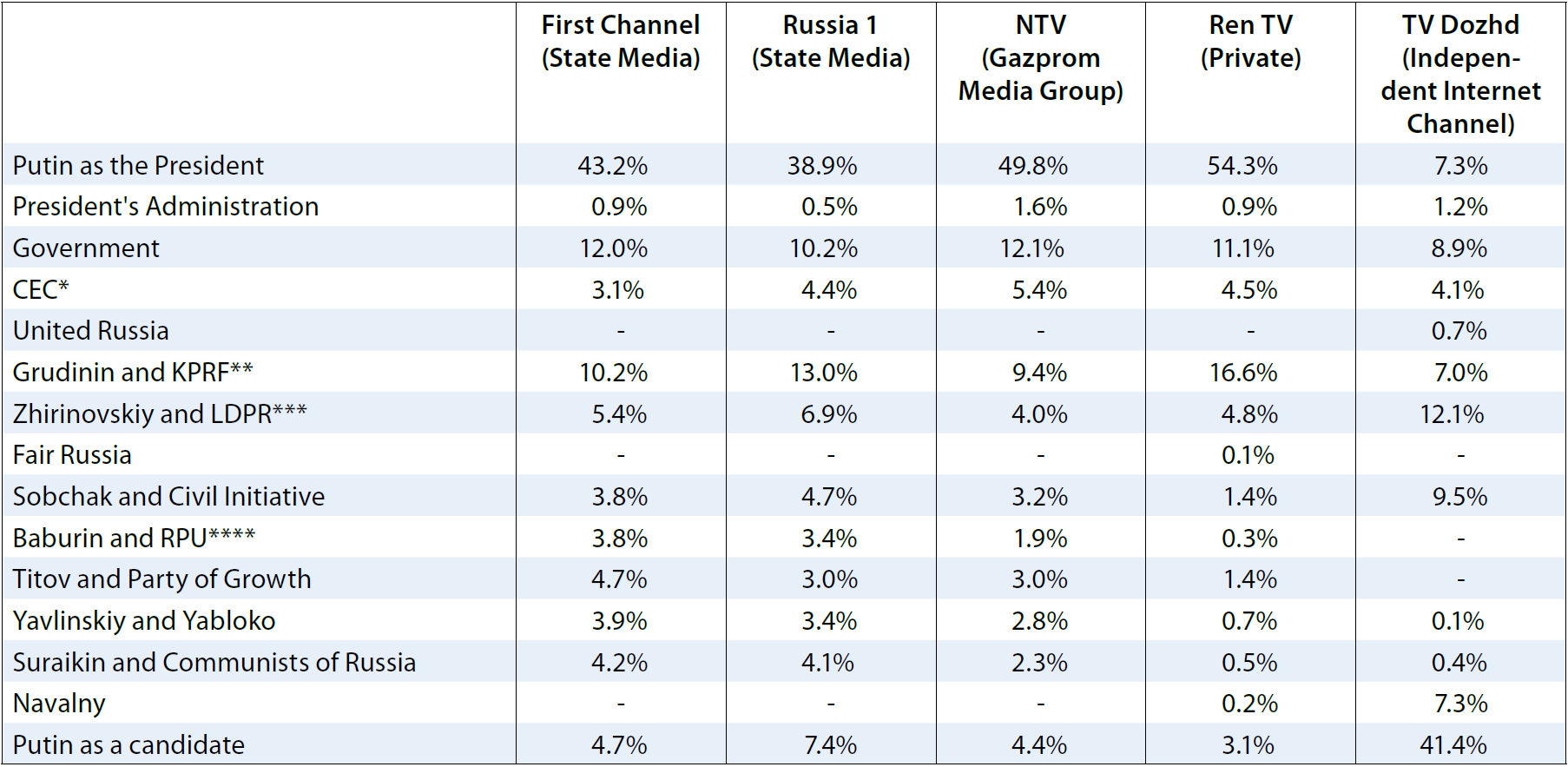

As the tables below illustrate, Putin’s victory margin was almost 65 percent, the highest in the post-communist era. His vote total exceeded 56 million, over ten million more votes than he received in the previous presidential election. Voter turnout reached 67.5 percent, up from the previous presidential election but below the 70 percent figure that the Kremlin apparently set as its goal.

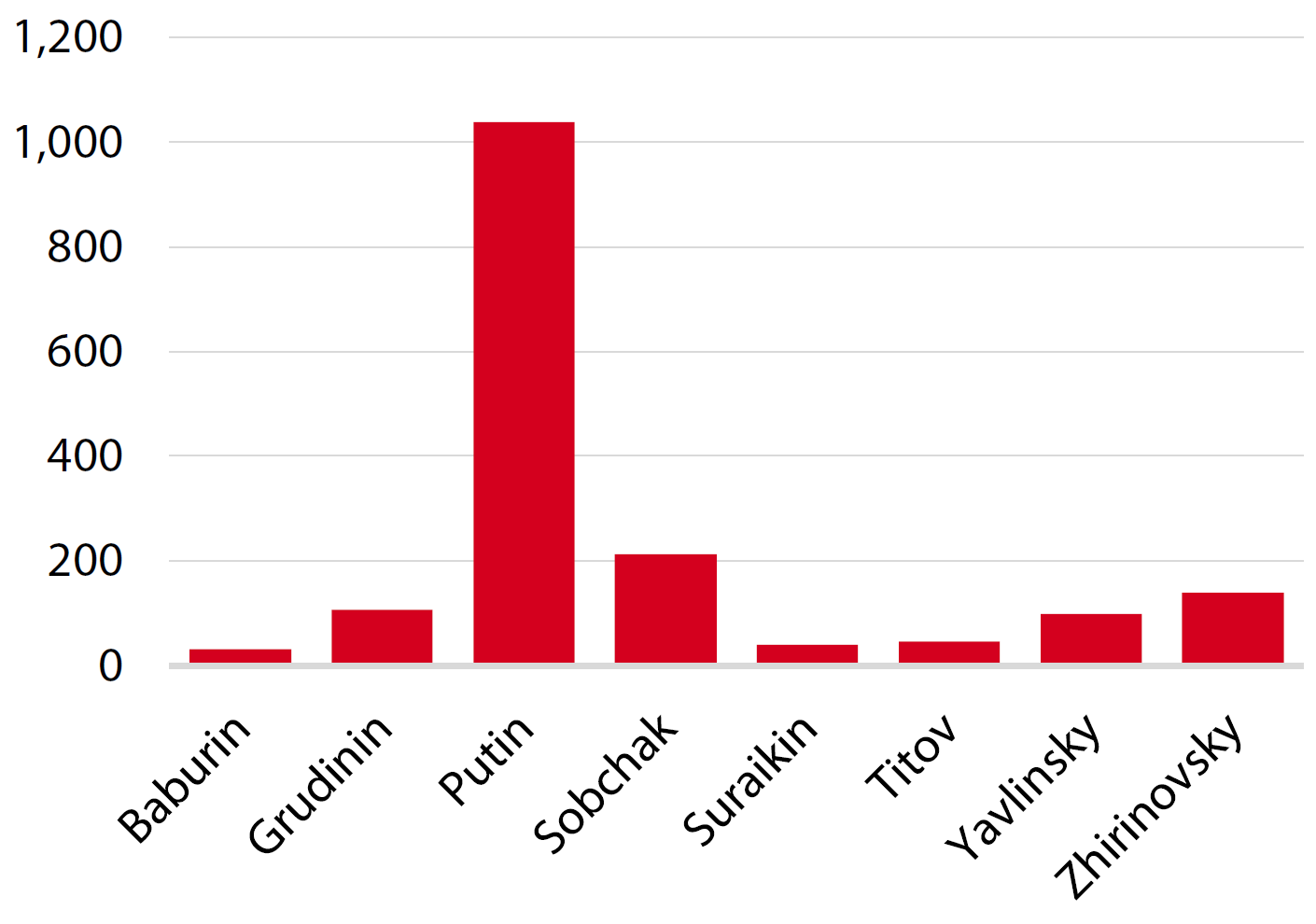

Figure 1: Russian Presidential Elections Results

Putin’s Winning Strategy

To engineer these impressive results, Putin and his political allies pursued a carefully calculated strategy, whose opening move was the exclusion from the presidential race of the Russian president’s most vocal and visible opponent, Alexei Navalny. An anti-corruption campaigner whose mastery of social media and internet memes had electrified some segments of Russia’s political opposition, Navalny was unable to contest the presidency because of a 2014 criminal conviction for fraud, a decision labeled “arbitrary and manifestly unreasonable” by the European Court of Human Rights. Following his disqualification in December of last year, Navalny launched a campaign to boycott the election as a means of sullying Putin’s mandate for his fourth and—under current constitutional provisions—final term of office.

Figure 2: Turnout in Russian Presidential Elections (Percent of Registered Voters)

If the official election results are accurate—and there is credible video evidence of ballot stuffing in some Russian precincts—Navalny’s appeals for a boycott were no match for the combination of rule changes, media exhortation, and administrative resources marshalled behind the official get-out-the-vote effort. In fact, by tossing down the gauntlet, Navalny encouraged the authorities to redouble their efforts to achieve a healthy turnout. For the first time in the post-communist era, the Central Election Commission allowed voters to cast their ballots outside the precinct in which they were registered, provided they had informed the authorities of their intent by March 12. Moreover, the Central Election Commission carried out a purge of voter rolls prior to the election in order to remove approximately 1.5 million “dead souls” as well as voters who were registered in multiple districts. Without this initiative, turnout figures would not have increased appreciably from the last presidential election.

As in earlier electoral contests in Russia, state officials, from governors to university administrators, served as prodders and proctors to boost turnout in the election. In one provincial university, students faced eviction from their dormitory if they didn’t turn out to the polls. As observers from the OSCE revealed, governors in some regions organized competitions among electoral commissions and “offered monetary rewards for PECs [Precinct Electoral Commissions] with the best performance and the highest voter turnout” (Interim Report 2018). Despite the full-court press to mobilize voters, turnout varied widely across the country, with some regions in Western Russia and Siberia lagging 35 points behind the ethnic republics of the Northern Caucasus and Tyva, which are the perennial front-runners in voter turnout in Russian elections.

No Level Playing Field

Whether in Russia or the West, the electoral playing field is never level when an incumbent is in the race. A sitting president in any country enjoys greater media attention because the daily tasks of governing shine a spotlight on the incumbent that is not available to challengers (see table below). In the Russian case, however, the Putin campaign was able to control the rules and the narrative in ways that constantly played to the strengths of the incumbent while highlighting the vulnerabilities of his opponent. For example, the authorities moved election day up by a week to coincide with the fourth anniversary of Russia’s annexation of Crimea, which remains a wildly popular decision in Russia. President Putin arranged to give his State of the Union address (Poslanie) just a little over two weeks before the election, an address that dominated several news cycles because of its dramatic claims that Russia possessed novel weapons systems for which the West has no answer. Even the ballot itself presented President Putin in a distinctly favorable light. Vladimir Putin’s name stood out in the middle of the ballot with its brief two-line biography, while all of his contenders had unwieldly six to eight-line descriptions of their backgrounds. More importantly, the ballot listed Putin as a “self-nominee” [samodvyzhenetz], whereas the other candidates stood under a party banner at a moment when parties were the least respected of all Russian political institutions (Levada Center 2017).1

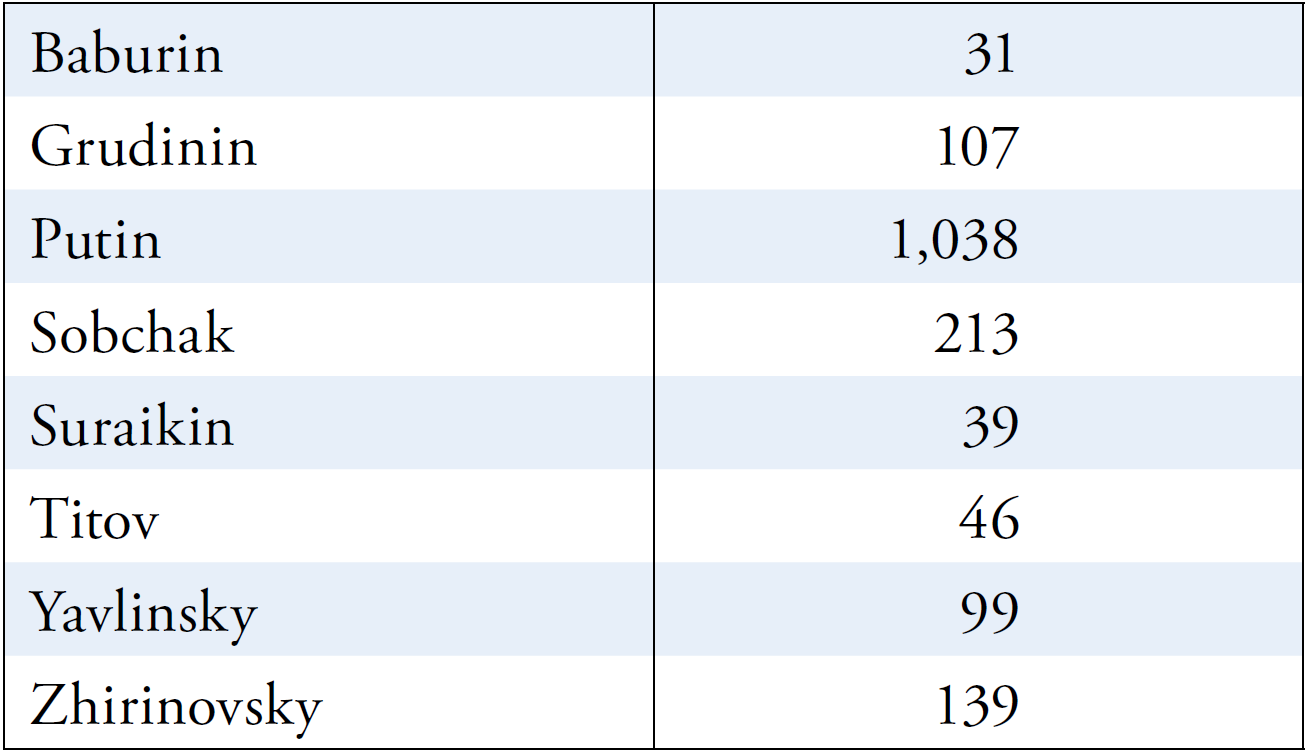

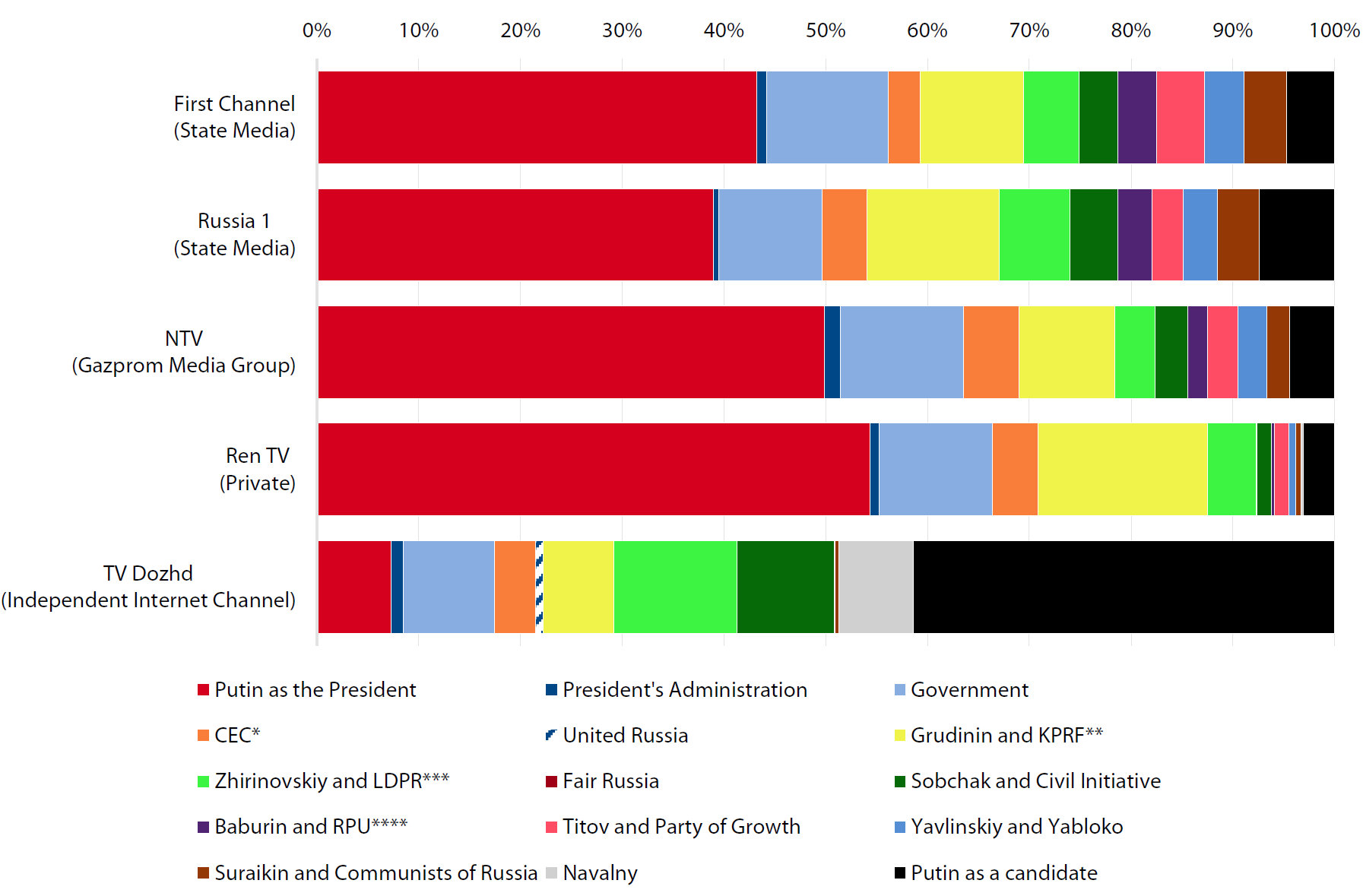

Figure 3: Mentions in Leading Russian Press Outlets (February 19 – March 16, 2018)

During the electoral campaign, the advantages of incumbency in a soft authoritarian regime were on full display on Russia’s main evening news broadcast, Vremia, which treated its viewers to campaign coverage that set President Putin apart from the seven other contenders for the presidency. Each broadcast offered a short segment devoted to the campaign activities of Putin’s opponents as they traversed Moscow and the country in search of votes. This daily news block on the election always ended with coverage of the Putin campaign, without featuring Putin himself. While the president was pursuing the Russian equivalent of the Rose Garden Strategy, his designated electoral agents [doverennye litsa] were pictured on the hustings. Among these agents was an assortment of celebrities drawn from the worlds of culture and sports.

The Seven Dwarfs

Set against the star power of the Putin team was a rag-tag band of opposition candidates for the presidency, whose backgrounds and behavior were no match for the sober, dignified, and professional image projected by President Putin. During one of the presidential debates, Vladimir Zhirinovsky, the mercurial leader of the nationalist Liberal Democratic Party, hurled sexist insults against the only woman in the race, Ksenia Sobchak. Sobchak responded by dousing him with a glass of water. In another debate, the candidate representing the Communists of Russia, Maxim Suraikin, had to be physically restrained on stage as he charged a designated agent standing in for the candidate of the Communist Party of the Russian Federation, Pavel Grudinin.

Where most of Putin’s opponents escaped frontal assaults by the country’s media, almost all of which are pro-Kremlin, that was not the case with Pavel Grudinin, the millionaire businessman-cum-Communist who finished second in the presidential race. The vitriolic news anchor for Vremia, Kirill Kleimenov, relentlessly criticized Grudinin’s business practices and his family’s ownership of luxury properties abroad, including ones in what Kleimenov called the “NATO country of Latvia.” Kleimenov claimed that such links to the West should be a disqualifying factor for a Russian presidential candidate. This tactic was emblematic of Putin’s campaign, and of Putin’s leadership more broadly, which has sought support and legitimacy in its championing of what one observer called “anti-Western, isolationist, and conservative values” (Kolesnikov 2018). Portraying Russia as the perennial victim of the actions of nefarious Western elites, who seek to demean and diminish Russia through indignities ranging from doping scandals to economic sanctions, Putin offered himself to the nation as the only guarantor of Russian security, honor, and grandeur.

What Next?

The question now is what the Russian president will do with the resounding mandate achieved in the March 18 “referendum on Vladimir Putin,” as two Russian journalists dubbed the election Sunday evening (Altekar’ and Ruvinskii 2018). The opposition may be in complete disarray, but Putin still faces serious challenges to his presidency from a range of domestic and foreign policy issues, from a shrinking labor force and increasing pension commitments to the morass in Syria. In recent years Putin has postponed confronting Russia’s systemic problems by deflecting attention onto foreign adventures and by offering the “balm of righteousness” (Carter 1996, p. 109)2 to a nation whipped into a frenzy about its unfair treatment by the rest of the world. It is unclear how much longer Putin can rely on these tactics to sustain his personalist regime.

At an impromptu press conference immediately after the election results were announced, a journalist asked the Russian president whether “in the next six years we will see a new Vladimir Putin or the old one?” Putin’s response: “Everything changes…we all change.” At the moment, though, change does not seem to be in the offing.

Bibliography

Altekar’, Pavel and Vladimir Ruvinskii. “Kogo pobedil Vladimir Putin,” Vedomosti, March 18, 2018. <https:// www.vedomosti.ru/opinion/articles/2018/03/18/754114-kogo-pobedil-vladimir-putin>

Carter, Dan T. The Politics of Rage: George Wallace, the Origins of the New Conservatism, and the Transformation of American Politics (Baton Rouge, LA: Louisiana State University Press, 1996)

Institutional Trust, Levada Center, October 11, 2017. <https://www.levada.ru/en/2017/11/10/institutional-trust-3/>

Interim Report (5 February – 1 March), OSCE Office for Democratic Institutions and Human Rights, Election Observation Mission, Russian Federation, Presidential Election, 18 March 2018, p. 4. <https://www.osce.org/odihr/ elections/russia/374137?download=true>

Kolesnikov, Andrei. “Frozen Landscape: The Russian Political System ahead of the 2018 Presidential Election,” Carnegie Center Moscow, March 7, 2018. <http://carnegie.ru/2018/03/07/ frozen-landscape-russian-political-system-ahead-of-2018-presidential-election-pub-75722>2

Notes

1 Polls conducted by the Levada Center in October 2017 showed that political parties were viewed as completely trustworthy by only 19 percent of the population; the corresponding figure for the President was 75 percent.

2 The phrase was used to describe George Wallace’s rhetoric and actions directed to white Southerners, whom he cast in the role of victims, in this case due to the imposition of Northern values on the South.

About the Author

Eugene Huskey is William R. Kenan, Jr. Professor of Political Science at Stetson University in Florida. Among his many works is Presidential Power in Russia. His latest book, forthcoming from Rowman & Littlefield, is Encounters at the Edge of the Muslim World: A Political Memoir of Kyrgyzstan.

Appendix: Data Tables

Table 1: Russian Presidential Elections Results (Percent) (Data for Figure 1)

Table 2: Turnout in Russian Presidential Elections (Percent of Registered Voters) (Data for Figure 2)

Figure 3: Mentions in Leading Russian Press Outlets (February 19 – March 16, 2018) (Data for Figure 3)

Documentation

Election Report by the “Golos” Movement

The Movement for the Defense of Voters’ Rights “Golos” (golosinfo.org)

Moscow, March 19, 2018

Preliminary statement based on the results of election observation for the March 18, 2018 presidential elections in the Russian Federation

The movement “Golos” carried out long- and short-term observation at all stages of the election campaign during the 2018 presidential race in the Russian Federation.

On election day, the “United Call Center Hotline” received more than six thousand calls. The “Map of Violations” crowdsourcing service received three thousand messages during the entire campaign, including two thousand on Election Day.

In the preliminarily assessment of the presidential elections, “Golos” acknowledges the definite strong result of the winning candidate but regretfully declares that the movement does not recognize these elections as truly fair, i.e. fully consistent with the Constitution, the laws of the Russian Federation, and international election standards because the election results were achieved in an unfree, unequal, and uncompetitive election campaign. This fact does not allow “Golos,” therefore, to assert that the will of the voters was expressed as the result of a free election campaign.

Recorded cases of fraud and violations regarding election procedures, including during ballot counting, require additional verification and detailed analysis of videotapes from the polling stations, which the movement “Golos” began on March 19.

Specific examples illustrating the findings by “Golos” can be found in the reports and statements of the movement (https://www.golosinfo.org/ru/zayavleniya), in the “Election Day Chronicle” on the movement’s website (https://www. golosinfo.org/ru/articles/142551#/), as well as in the messages on the “Map of Violations”.

Characteristics of the Election Campaign Before Election Day

- The elections of the president of the Russian Federation in 2018 took place in a limited-competition environment. In many ways, this is due to the existing restrictions on passive electoral citizen rights and to the nature of media reporting on the elections.

- The artificial mobilization of an administratively-dependent electorate using various technologies came as the result of the lack of competition in the presidential race and as a reaction to the election boycott campaign (promoted by Alexei Navalny). Another special feature of the campaign was the widespread involvement of underage citizens, both in the mobilization of voters and in direct political campaigning.

- At the same time, the movement would like to stress the positive role of election commissions, which significantly increased the amount of information provided to citizens about opportunities to participate in the elections.

- Coverage by the mass media was characterized by the manipulative and tendentious nature of information on candidates, in strong part because the media is to some degree controlled by the state. Such a situation prevents citizens from obtaining objective and reliable information about candidates. The incumbent President Vladimir Putin’s election campaign activities had a significant influence on the voters’ will due to his official title and the widespread coverage by the media.

- In comparison with previous presidential elections, the election commission system was much more open. In general, interaction with the observer community has improved, including on the election day.

- The CEC of Russia created a more convenient voting system for the voters “at the current location,” in a polling station other than the place of residence which, however, did not eliminate the possibility of administrative abuse.

- On the eve of Election Day, the state increased pressure on civil activists and independent observers. This pressure manifested itself in attempts to obstruct the activities of independent observers during formation of a call center, as well as in the use of political surveillance and “black PR” against them. Thanks to the intervention of the Chairman of the CEC of Russia on the eve of Election Day, pressure on the movement “Golos” was minimized.

- There were many cases of pressure on voters expressing the wish to realize the right not to participate in the vote.

Preliminary Observation Results on Election Day

The new voting procedure “at the current location” was used for executing compulsion to vote: there were records of special voter lists, organized voter transfers, and activities to monitor voters’ participation in the voting process. Many reports came from polling stations located on or near the grounds of student dormitories, colleges, and large enterprises. Voter “migration” within districts significantly exceeded voter “migration” between districts (For more information, see the express analysis: www.golosinfo.org/en/articles/142556). In total, about 5.7 million people applied for voting “at the current location.” The number of cases of “migration” between districts seems to be just over 1 million voters, and the “migration” within districts is estimated at more than 4.5 million. In total, almost 30% of the total number of “migrants” were attached to a limited number of 4,821 (out of approx. 96.000) polling stations.

In preparation for Election Day, about 2 million records were removed by the election commissions from the voters’ lists, including “voter doubles” (one person counted twice) and so-called “dead souls” (fictional or dead voters). In some regions, because of these activities, real voters were also removed from the lists. In most regions, the number of voters increased significantly from the beginning of Election Day to the end of voting: e.g. a 2.1% increase in North Ossetia-Alania and a 3.1% increase in the Moscow region and in St. Petersburg. In sum, the number of voters on the voters’ list increased on Election Day by almost 1.5 million.

The following cases were observed: 1) the “books” of voters’ lists that had applied for voting “at the current location” were not bound, 2) there were illegal notices in the voters’ lists, 3) on March 18, precinct election commissions began to grant voting rights to persons with temporary registration, as well as to persons who were absent from supplementary voters’ lists, without legal grounds for doing so.

“Golos” positively evaluates the decrease in voting outside the voting premises (the so-called “home vote”) compared to cases in previous presidential elections, from 8.2% down to 6.6%. Nevertheless, observers noted on Election Day cases in which the election commissions came to voters who did not submit applications for “home vote” and cases of voters who submitted such applications but were not visited by precinct commissions.

On the eve of Election Day, observers in some regions found that in printed versions of the precinct election commission workbooks, there was information on banning photos and video capture by members of the commission with advisory vote. As a positive development, the CEC of Russia promptly reacted to the identified problem and issued explanations. Reports of non-admission of observers and members of the commissions with advisory vote (sent by parties and candidates) came from Moscow city, Krasnodar and Khabarovsk regions; Bashkortostan; Dagestan; Karachaevo-Cherkessia; Kemerovo, and Nizhny Novgorod and Moscow regions.

Observers noted problems with the organization of video broadcasts from precinct election commissions (PEC). Specific PEC names with installed cameras were not published in advance. Observers also report numerous facts of bad positioning of video cameras, which did not allow the observers to realistically follow what was happening in the polling stations (e.g. poorly-visible ballot boxes). In some cases, members of election commissions deliberately tried to decrease the chances for video observation, obstructing the camera view by foreign objects, including during the ballot counting.

There were reports from different regions about ballot box stuffing (some of them recorded on video), and about possible voter impersonation.

“Golos” positively assesses the decline in some turnout figures, as compared to the previous presidential elections, which previously caused serious doubts among the observers. At the same time, preliminary results of turnout assessment by video cameras in several regions (Dagestan, Tatarstan, Tyumen region, Chechnya, etc.) show serious discrepancies with the official results.

The proportion of procedure violations in the entire country were noted in less than 5% of the received observers’ questionnaires. Nevertheless, for three procedures and requirements of the law, the overall level of violations was high. Below are the three violations, which exceeded 5%:

1 Restrictions on the movement of observers inside polling stations: 5.7%;

2 Violation of the sequence of stages of ballot counting: 12.0%;

3 Conducting different stages of ballot counting at the same time: 12.2%

EPDE Protests Against Classification As “Undesirable Organization” in Russia

Berlin, 14.03.2018

On 13 March 2018, the European Platform for Democratic Elections (EPDE), a civil society network of independent election observation organizations, and its Lithuanian member International Elections Study Center (IESC) were classified as “undesirable organizations” by the Ministry of Justice of the Russian Federation.

Stefanie Schiffer, EPDE board member, commented: “We protest against the listing as “undesirable organization” and against the wholesale criminalization and discrediting of our network. We demand the immediate withdrawal of this measure by the Russian Ministry of Justice.

With the law on “undesirable organizations” introduced in 2015, the Russian government attempts to criminalize the international cooperation of democratic movements. Employees of listed international organizations and their partners in the Russian Federation may face up to six years imprisonment, a ban on entering Russia and numerous other sanctions for continuing their cooperation.

The German government criticized the law in 2015 as a “measure to isolate and discredit the critical civil society in Russia and to prevent cross-border cooperation,” which even increases the “sense of insecurity and fear that already exists in the Russian civil society”.

EPDE is an alliance of electoral observation organizations founded in 2012 with the aim of supporting citizens’ election observation in the countries of the Eastern Partnership, in the Russian Federation and throughout Europe, and to contribute to democratic electoral processes.

More about EPDE: www.epde.org

Statistics

Coverage of Candidates in the Russian Presidential Elections 2018 by Various Russian TV Channels

Figure 1: Coverage of Candidates in the Russian Presidential Elections 2018 by Various Russian TV Channels

Documentation

Results of the Presidential Elections 2018

Figure 1: Results of the Presidential Elections 2018

Thumbnail external pageimagecall_made courtesy of kremlin.ru. external page(CC BY 4.0)call_made

For more information on issues and events that shape our world, please visit the CSS Blog Network or browse our Digital Library.